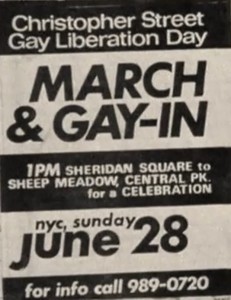

WHEN LESBIAN, GAY, BI, AND TRANS people took to the streets on June 28, 1970, one year after the historic uprising in New York City’s Greenwich Village which changed the course of LGBT history, it was not a parade. It was a political action.

The “March and Gay-In” from Sheridan Square to Central Park was organized to commemorate the victory of the Stonewall Riots, and it was tempered by anger and fear. The gay community had a message: we will have the same rights as everyone else, whether they like it or not. And whether my LGBT brothers and sisters knew it then or not, they marched not only for their freedoms but for the rest of the nation as well.

The New York City LGBT March, which has sparked Gay Pride festivities worldwide since 1970, carries a great burden. It is mistakenly called a “parade” by many who see only Dykes on Bikes or half-naked gays dancing in the streets. The March is an expression of individualism and freedom, and it is a call for equal rights. It is an event which seems not to speak to those whom LGBT rights do not directly affect. But the heterosexual community should take note; as conservative factions struggle for a homogeneous America, they forget that our nation was built on diversity.

The greatest obstacle to the LGBT rights movement is the belief by those who oppose it that homosexuality is a “lifestyle choice.” That there are as many lifestyles as human beings on the planet doesn’t stop the phrase from being applied to the LGBT community as if we were a unit. And the fact that science still does not fully understand the biology of homosexuality doesn’t negate the presumption of “choice.” Those who apply the phrase to gay lives presume that living differently than they is detrimental to the fabric of society. And if those factions will come for gay people, they will eventually come for everyone who is different.

On June 28, 1969 homosexuality was thought to be a perversion, an illness, and morally bankrupt. (Yes, I know some people still think like this.) Any bar serving gays and lesbians could lose its liquor license. The New York State Liquor authority had made it clear that, based on their interpretation of a law prohibiting disorderly conduct in bars, the very presence of LGBT people created disorder. The FBI kept track of any mail pertaining to homosexuality, who it went to and who sent it. It was unlawful to dance with someone of the same sex (considered a public act of lewdness, which was illegal). It was illegal, in New York, to dress in clothing of the opposite sex unless three articles of clothing were of your own gender. (Take a moment to imagine that meeting of the legislature!) Earlier in the decade, police entrapment of gays, resulting in arrests and public exposure, was a regular occurrence. While straight couples had their lovers lanes, LGBT people would be arrested on charges of public lewdness. Names and addresses could be printed in the newspaper. Lives were ruined if you were known to be “deviant.” Homosexuals were fired from jobs, arrested, sent to mental institutions.

Violence was something gays had learned to live with. Even in NYC, where many had come to escape persecution, being gay meant being on the alert. There was a degree of freedom – at least in comparison to the rest of the nation – but homosexuals were bound by laws and ordinances based on misplaced morality, pseudo-science and paranoia. Just as Jim Crow had debased the black community, laws assuming the “perversion” of the LGBT community kept gays in the shadows. (It was not until 2003 that anti-sodomy laws, used to persecute homosexuals even though heterosexuals can also engage in it, were declared unconstitutional. Justices Antonin Scalia and Clarence Thomas and the Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist were the only three voices in dissent.)

On June 28, 1969, in the wee, Saturday morning hours, the police, conducting one of their regular sweeps to clear out the homos, stepped into a boiling stew. The week had been a scorcher and the Stonewall Inn, a regular spot for police raids, was a pressure cooker. Homosexuals looking for their weekend fun filled the bar and paid for its overpriced, mafia-poured drinks. The Inn had been raided once already that week. Add to that dangerous recipe years of abuse by civilians and authorities, stir well with police brutality, derision and psychological abuse, add a pinch of the previous raid, the day’s heat and… well… it had been a bad week.

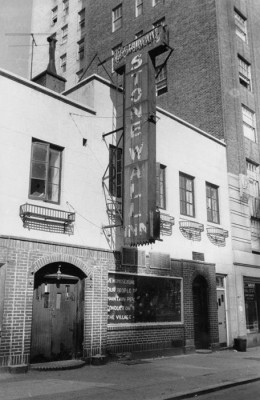

The Stonewall Inn at 51-53 Christopher Street, NYC, in 1969 (credit: Diana Davies, wikipedia commons)

Instead of quietly getting into the paddy wagons and making catty remarks as usual, the men and women at the Stonewall Inn fought back. The police tried to make their arrests but some of the gays threw pennies at the “coppers” and shouted insults. Conflicting stories exist about what actually sparked the riot but I suspect many things happened at once. What is certain is that as it escalated, the small clutch of police was suddenly the target of the full force of gay anger – a sudden, explosive and unstoppable release of bottled emotions. Those few officers and a pair of reporters from The Village Voice retreated into the bar as gays attacked – literally – from outside. (The Village Voice was just down the street in the place where The Duplex, that popular Village piano bar and cabaret, now stands.) The protesters outside began to throw stones, bricks, pumps and purses. One group tore a parking meter out of the ground to use as a battering ram. When the riot police came, the gays were in full swing. They would not back down. The uprising went on for two days, with the gays declaring victory.

Mobilized by that brief but violent skirmish, the “March and Gay-In” on the anniversary, June 28, 1970, was organized to commemorate what was now being called Christopher Street Liberation Day. The march route went from Sheridan Square to Central Park and would bring the LGBT community into public view. The men and women who marched did not know if they would make it from one place to the other. The violence of the previous year’s uprising in which civilians and law enforcement alike were injured and beaten was still fresh in the mind, but The March was a necessity. The Stonewall Uprising (I prefer “uprising” to “riots”) had not changed any laws, but it had changed the gay psyche.

This was no parade. It was an act of defiance.

America guarantees freedom in the pursuit of happiness. If homosexuality is a conscious choice, should my rights be diminished because my private life is in discord with the majority? Theoretically, freedom of choice is the majority, so why can’t I choose to be gay and still maintain my civil rights? Biological discussion of homosexuality is secondary to the fact that our Constitution guarantees us rights enabling “the pursuit of happiness” mentioned in the Declaration of Independence. Since biological arguments bear no weight on those who oppose it, the political argument throws light on a wider issue: we may pursue happiness in whatever way we choose. The caveat is that it happens between consenting adults and does harm to no one else.

We all make choices and those choices vary with the seasons, with the individual, with the wind. If I woke up tomorrow and decided to wear a blue bonnet and wooden shoes, no one could stop me though you know there is some dunce who has it out for blue bonnets. You may offer advice about what you think is a “better” lifestyle, what is safer, stronger, more moral or simpler. You may prefer to live your life in a quiet suburb, attending mass, temple or going to the mosque for services. You may express yourself in art, music, dance, science or “big business.” Or maybe you prefer utter hedonism. But if you are threatened by something I do in the privacy of my own home, or, for that matter, if you are threatened by my green hair, my holding hands with someone of the same sex, or my wearing flip-flops in the summer, you should spend time in self-examination – better known as therapy. What makes you so insecure? Your criticism of my lifestyle choice is an opinion, not a mandate. In other words, it’s your problem.

In America, the norm is that we all deserve the same rights. Diversity trumps conformity.

As gay people across America anxiously await decisions in the two LGBT marriage-rights cases currently in deliberation at the Supreme Court (rulings are set to be handed down this month), people of varying sexuality, gender-transition and self-identification still fight for basic respect. By the time we get to this year’s NYC March, on June 30, we will know whether the U.S. Supreme Court has ruled in favor of freedom or fear. It will either be the most thrilling march on record since the 1970 or the angriest.

Brace yourselves.

We continue to march in the fifth decade after the Stonewall Uprising, marching not only for our own civil rights but for yours. We march because as long as there are those who would stomp out diversity, as long as there are those who fear themselves, as long as there are those who ask why we march, we must.

Pingback: Why The Pride March is Your March Too — The Good Men Project