I ran into the kitchen to find my mom reading her Time magazine and smoking a Carlton in our sunny breakfast nook. It was a hot, sticky Saturday, July 1976, bugs and lawn mowers humming outside, attic fan whirring above.

We were both barefoot and shiny with light sweat. She was one year into medical school, into which she’d enrolled at age thirty-three, and she was taking a break from intense study. In our living room sat a crate stuffed with a complete, dismantled human skeleton, on loan from Emory University. Even the tiny ear bones – the hammer, the anvil and the stirrup – were included in a little pouch. Medical textbooks littered the house, spines cracked, pages dog-eared and strewn with cigarette ash.

My dad was four years dead from driving drunk, so my mom was as single as a single mom could get and frequently stressed out; I usually let her decompress undisturbed after a week of classes, but I had big news.

“Guess what?” I said, turning on the tap and angling my head under the faucet. As I drank the cool water, my hair fell into a dirty dish. I looked up at the grease-browned clipping tacked to the wall above the sink, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution headline dated August 8th, 1974: NIXON RESIGNS. For my mother, this held all the significance of a holy relic, a touchstone to her most exuberant day of “I told you so!”

“Mommy,” I repeated, bursting. “Guess what?”

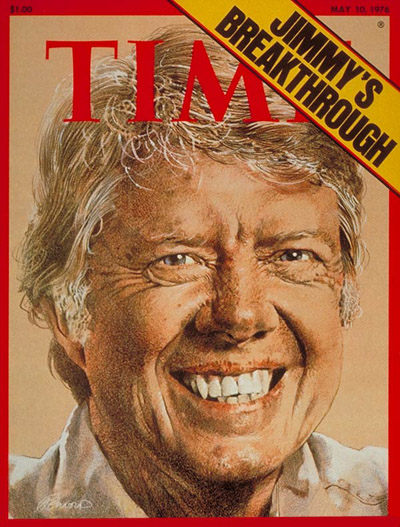

“Let me finish this article, please…” She conveyed duress in every syllable. She was reading about former Georgia governor and presidential hopeful Jimmy Carter, who grinned clown-like from the magazine cover. Mom was deeply invested in the former peanut farmer, hoping against another slaughter like McGovern ’72, the unofficial death of the counterculture dream.

I poured myself a cup of coffee and dutifully waited. If Mom was home, our Mr. Coffee was rarely empty. She drank at least a pot a day, with non-dairy creamer and sugar. I had taken it up a few years previously, at age eight, and I was hooked. I always drank it hot, even if the afternoon temps hit the 90s, which they usually did in high summer. Iced coffee, for some reason, revolted me.

I scooped in Coffeemate and two spoonfuls of sugar, sat on a stool and drank out of a warmed Strawberry Fair cup. This was my mother’s wedding china. As long as I could recall, we’d used it as everyday ware: Johnson Bros. Strawberry Fair, a delicate rose-colored pattern of strawberry vines against pale white ceramic; it was the chipped yet classy crockery of my childhood.

I idly hummed “Silly Love Songs,” the anthem of the summer of ’76.

Mom slapped her magazine down. “What, honey?”

“Todd won the whole Beatles catalog!” I blurted. I’d run home from my best friend and neighbor Todd Butler’s to share these good tidings. Saying the words gave me a thrill.

Mom was an original Beatle fan. She’d framed the black and white 1967 Richard Avedon banner (available via Look magazine for $1.50), and those four faces stared down on me from the dining room wall every day; she often played Revolver, Rubber Soul, the White Album, Sgt. Pepper, and Abbey Road, all of which my brother and I had sung along to since we were toddlers; the Beatles were the soundtrack to her finding herself after she left my dad in ‘65. Even at eleven, I understood this. I knew she’d be excited for Todd, and we’d share the excitement.

“He what?” Mom said, confused, but focused.

“Well we’ve been listening to WQXI nonstop and if you’re the thirteenth caller when they play a Beatles song your name gets put in a bucket and Todd called in and got his name in the bucket when they played ‘Taxman’ and that was last week and they called him at home today and told him they pulled his name out of the bucket and he won every Beatles album ever made!”

“Every album? How many is that?”

“Seventeen! That’s a lot we don’t have!”

Mom frowned and lit up another Carlton.

“Isn’t that so cool?” I said. “He gets to pick ‘em up on Monday at WXQI!”

Mom shook her head, bit her lip, gazed at the withering azaleas outside the window.

”Isn’t that so cool?” I repeated. “Mommy…?”

She forced a smile. “Um, yeah, it is. That’s a… wonderful thing. Seventeen albums. And how old is Todd now?”

“He’s eleven, Mommy. You know that.”

“Yeah I know that. Eleven. An eleven-year-old kid has every Beatles album.”

“What is it? Mommy? Is that… bad?”

“Well, he’s not a real fan,” she said. “He doesn’t know. He can’t… appreciate such a… such a… treasure.”

“He is a real fan, though,” I was anxious to let her know. How could she not know? I was still hoping to light her up. “He loves Wings, too.”

This was all true. Todd already owned a couple slightly warped, very scratched Beatles albums, passed down from his brother, and he had the new, hit Wings At the Speed of Sound LP, and played them all incessantly as he drew the covers in pencil in his Academie sketch book.

“OK,” Mom said, sighing. “OK. Tell him I said congratulations.” She shook her head again and turned back to her magazine.

My mom was jealous. Of my best friend. This filled me with a lonely kind of sadness, twined with a compulsion to say or do something that would spark the air, make everything all better. But a familiar vibe radiated from the nook: leave me alone. She dragged on her smoke and turned the pages of her Time. She wasn’t actually reading. Just waiting for me to go.

I sucked down the rest of my coffee and drew from the caffeine-and-sugar spike in my blood. I headed back up the steaming street to Todd’s, squinting against the glare, the merciless sun on my tanned, wiry arms.

I’d left Todd fitfully picking out the “Day Tripper” riff on his acoustic, and giggling. In the wake of his win, he’d suddenly become obsessed with finally learning to play the cheap guitar that was gathering dust in his house. Fortune had smiled upon him, and all was forward motion, like a cool river current calling me to step in.

~

Todd was still hacking away at the “Day Tripper” riff when I walked in to the chill of his family’s living room. (The Butlers’ door was never locked during the day.) There he was, rocking over his instrument. He had nailed the riff and was playing it over and over and over in a kind of trance, sunk into a plush chair, his red hair plastered to his forehead despite the ever-present AC, his chubby hands as active as when he drew pictures.

“Good Lord, Todd!” his father called from the den, where he lay supine on his duct-taped La-Z-Boy, swathed in a cigarette fog, sort-of watching the afternoon movie while Mrs. Butler fried chicken in the kitchen. “You’re gonna send me ‘round the bend if you don’t… modulate or… something.” His voice was somehow proud and exasperated at once. Mr. Butler was an erstwhile cocktail lounge pianist and writer of piano instruction manuals who now worked as an exterminator.

Todd kept at it, actually laying into the riff harder, louder, as Mr. Butler groaned in mock defeat. Finally, Todd made a mistake and stomped his foot on the carpet.

“Damn!” he yelled. “Dammit shit!”

“Todd!” his dad protested, not moving a muscle except to suck on his Pall Mall. “Imma wash your mouth out with soap, son.” Then he chuckled at the idea, which was, in fact, a joke. Todd’s parents were not keen on discipline.

“That sounds great,” I said. “Just like the record.” It did. The right notes, the right feel. My friend was cracking the code.

Todd nodded and wiped hair from his face, panting. “Wanna stay over tonight? Late Movie’s Godzilla vs. Mothra.”

“Yeah, I’ll call my mom.”

“Did you tell her about my albums?” his face brightened as he returned fully to this plane.

“Yeah, it blew her mind.”

“We could stay at your house instead of here,” Todd said, flicking his gaze toward the den, irritated at his father for daring to try to shut him down. “Your house is the best. Your mom is the best. Your pillows are the best. They’re cool underneath.”

Like most of my friends, Todd had a little crush on my mom. And he loved rooting through the skeleton crate, holding up various bones and the halved skull, weighing them in his hands, and poring over Mom’s medical books, some of which featured graphic photos of horrifically diseased or wounded bodies. (Elephantiasis! Herpes! Syphilis! Sucking chest wound! Foot cut off by a lawn mower!) But mostly he loved the gorgeous Gray’s Anatomy drawings of interwoven muscles and nerves and systems; these could captivate him for hours.

“Your TV’s better than ours,” I said. This was true. I also didn’t want to subject Todd to my mom’s jealousy. She would very likely unwittingly say something negative and break the spell of Todd’s win, which, in the confines of Todd’s house, still hung in the air like a scent, co-mingling with the intoxicating smell of Mrs. Butler’s fried chicken.

“Fine,” he said. He held his guitar up for me to hold while he extricated his overlarge body from the chair. The neck of the instrument was slick with sweat. “I could show you some stuff,” he said, nodding to the guitar.

“Maybe later,” I said, not yet ready to answer the muse’s call, which was rising yearly. My mouth watered for the boxed crackers, sweets, and assorted goodies in the Butler kitchen, where we were never told, “Wait! That’ll ruin your appetite!” Because nothing ever did.

~

Todd’s parents were long asleep, Godzilla vs. Mothra was long over, and my friend and I sat on the cooling stoop of his family’s front porch drinking Suisse Mocha flavor General Foods International Coffee in plastic tumblers, talking nonstop, and listening to the night sounds wax and wane in the creeping morning dew; nightingales, moths against the screens, persistent hum of electricity, intermittent dog barking, distant traffic like a river.

We talked for hours about him winning the Beatles records; time and again we replayed each event leading up to the fateful call from the WQXI DJ; we discussed the Godzilla movie, comparing it to our other favorite monster movies, like Destroy All Monsters, Dracula, and Godzilla vs. the Smog Monster, in which you could briefly see a woman’s boobs. We spoke ill of Jaws, which had come out the previous summer, and which we’d both been too terrified to see, but had heard about from our braver acquaintances.

“This skinny dipping girl gets totally eaten onscreen,” Todd said. “And a kid in a raft, too, with, like, explosions of blood and stuff.”

“No, no, no, no, no, no.” I said.

“I heard people totally puked in the lobbies. Yum!”

“Stop.”

Enlivened by talk of gore and vomit, Todd stood in the yellowy porch light. “Let’s walk to that lady’s house,” he said.

I knew who he meant: the hippie-ish, longhaired, twenty-something woman down the street. On the last Halloween we’d trick-or-treated, before we’d aged out of the tradition, she’d come to her door clad only in a sheet. This had been a couple years before, but the encounter haunted us.

I’d been dressed as a pirate, Todd in a professional-looking Frankenstein’s monster get-up he’d made in his room. His costume featured realistic stitch scars, electrical bolts epoxied to his neck, a dusty black suit, and green makeup on his face and hands. The piece de resistance was a headpiece he made from a brown lunch bag soaked in some kind of stiffening agent and affixed with fake black hair, giving an authentic rectangular-Frankenstein-head look. My pirate costume was merely a bandanna, a paper pirate hat, a plastic cutlass stuck in my belt loop, and a Groucho Marx nose taped to my glasses.

In prowling our usual circuit, we’d noticed the lights on in a duplex, the curtained door revealing a humble kitchen with a spice rack and dishes in the sink. As with every Halloween, we were bolder than usual. We knocked hard for a minute or so.

Just as we were turning to go, a figure bounded into the kitchen, footfalls on the floorboards softly audible. Through the dingy curtains, she was a blur. But then she opened the door. Holding a toga-ed sheet against her torso, her breasts defined against the thin cotton, she sized us up with open-faced glee.

“Oh my fucking god,” she laughed, smells of candles and pot wafting around her. “Ya’ll look AMAZING. I’m so sorry! We didn’t get any candy! God damn it, ya’ll.”

“Uhhh….”

Music trickled from a room. Bad Company. “Shooting Star.” I knew all the words.

“You’re Frankenstein, riiiiight?” she asked.

Todd made an affirmative grunt.

“That’s a fucking amazing costume, kid, where’d you get it?”

Todd found his voice: “I made it.”

“No shit!”

“I made mine, too…” I said, barely.

“You’re a pirate! I’m scared!” She laughed again, a kind of phlegmy bark, full of gusto, then looked back over her shoulder and frowned for a moment, then focused back on us with a lopsided grin.

“Sorry we don’t got any candy…” she said and pouted.

We both made gestures and sounds that all meant: that’s totally OK.

“Cool. Ya’ll’re cool. Be safe!” As she shut the door she said, “Happy All Hallows Eve!”

We rejoined the sentiment and watched her through cracks in the curtains as she slunk back through the kitchen, her ass buoyant beneath the sheet. She flicked the light off as she vanished into a dark hallway.

“Whoa,” Todd had said. “She was totally doing it with some guy back there.”

~

Now, several years later, we were walking back to the scene under bug-swarmed streetlights, two boys a little older, crazier, and braver, rock and roll ringing in our ears, the first whiffs of adolescence rising in our sweat. Todd, in fact, due to his rotundity, was sporting some impressive B.O.

“You ever see her?” I asked.

“Nope. She might not live there any more.”

“But she might.”

“Maybe we’ll get a look, she seemed like a total pothead, she’s probably up.”

We found the duplex. It was dark and forlorn, one side of it now entangled in kudzu, a screen dangling from the porch like a scab. Somewhere a cat yowled.

We stood in the flickery streetlight for a few moments, savoring the memory of the woman, saying nothing. What were we planning to do, exactly? Peep in her window, now that we were on the brink of full-on teen stupidity?

“Actually,” Todd broke the spell, “I think she must’ve moved away, now that I think about it.”

“She was totally fucking her boyfriend that night, though,” I ventured.

“You know it.”

We walked back the short distance to Todd’s house, the shadows lending all the familiar objects of our world a temporary mystery. Everything, including us, was soft, ill-defined; we could melt into the space between the dark and the bushes, the formlessness between the sleeping houses.

Todd gazed to the paling sky and gasped. “Looks like we’re staying up all night. We are. We’re staying up all night. Cool.”

“I’m not even tired,” I said.

“Me neither. Hey look.” He stopped at the corner of his street.

“What?”

“Did you know that without light, everything’s black and white? Look around, look at that house. That house is usually blue, but now it’s gray, right?”

“Wow. It is.”

“As the sun comes up, everything will get its color back. That’s what happens. Let’s go watch in the driveway!”

And so we did. As dawn crept over our neighborhood, we sat at the edge of Todd’s driveway and watched the colors come in. We stared for long stretches of time at individual objects. Minutes dragged by, slowly at first, then ever quicker.

“That car’s turning red!” Todd said. “It’s, like, purple, see? But it’ll be red soon!”

I saw, and thrilled at it.

“What do you see?” Todd asked. “Any green?”

I looked at the huge oak across the street. Sure enough, I could see green in the leaves where before I’d perceived only gray. I told Todd.

“Yeah!” he said. “I see it!” Then he sang, “It’s Not East Being Green” in a perfect Kermit the Frog impersonation.

“You could really be an imitator, like Rich Little,” I said.

“Impressionist,” Todd said, fatigue creeping into his voice. “It’s impressionist.”

“No it’s not,” I said, also suddenly tired. “It’s imitator.”

He harrumphed and was about to lean into his (correct) point when his eyes widened. “Check that out!” he said. “The bricks! They’re red now! Red, I say!”

The sky blazed in the east as color flooded back into our world with accelerating force, a transition heretofore unseen by either of us. The sun was not yet peeking through the pines, but we could feel its oncoming presence. I became acutely aware of time, of the moment, knowing I would remember; I was having a memorable experience with my friend, and he would remember, too. Years form now. I knew it. The certainty was oddly solid, heavy in my fluttery insides.

Cars began to pass, people waking up, starting their Sundays. The fascination exacted a toll, and as the sugar eked from our blood, we headed back to Todd’s room, past his parents’ bedroom, where Mr. Butler snored riotously and somehow Mrs. Butler slept through it.

In Todd’s room, we’d fashioned a fort that encompassed his bed and the foam mattress I slept on, plus some scattered crumby plates, his little turntable, and his existing Beatles records – Magical Mystery Tour and Hey Jude – which we’d pored over, reading what few liner notes we could find, sinking our attention into the photos. Todd had attached a sheet to a box fan he ran nonstop in his open window at night, the whirr of it helping lull him to sleep. The sheet billowed out over us like a parachute tent as we flopped onto our beds, the droning wind in our ears.

Todd reached over and started up his stereo, placing the needle on track one, side two of Hey Jude, which was the seven-minute title song. He plugged in his headphones and left them on the floor between us, where the song played out in tinny, scratchy miniature, faraway but right there, electric lullaby telling us to take a sad song and make it better, re-connecting us to his fantastic fortune, his seventeen Beatle albums, waiting for him, for us, like the rest of our lives.

Thanks so much for that … as a friend of Todd’s wife, Clare, I have heard a lot about him from her. This, right here, summed up the parts that I wish I knew. What a great friendship.

Did y’all make cassette tape of the albums for your mom? LOL … :-D

Again, thanks for sharing.

Hi Benita,

Thank you. Todd was such an important part of my life. Part of my drive to write about him is so people who didn’t know him will see a bit of why we all loved him so much and, hopefully, share his spirit. And no, we did not make cassettes for my mom. In later years she acknowledged that the LPs were put to better use with Todd (and me) anyway.

I knew Todd in San Francisco. He and Clare made such an impression on my partner Dante and I that I will always feel blessed to have known him and her. Thank you for this beautiful recollection. I felt like I was right there with you.

Thanks so much, Ric. More to come.

Pingback: Younger Americans: Bowie Through Our Eyes | The WeeklingsThe Weeklings

May I just say what a comfort to uncover somebody who

really knows what they are talking about on the web.

You certainly know how to bring an issue to light and make it important.

More people really need to read this and understand this side of your story.

I can’t believe you aren’t more popular because you most

certainly have the gift.