Before I start criticizing Greil Marcus, I should mention that I might have plagiarized his essay on The Band from his book Mystery Train for my high school senior-year term paper. I don’t recall lifting any sentences directly, but I’m pretty sure I bandied about an idea or two without the proper citation. Having talked my English teacher into letting me write about The Band, and having Greil’s essay on hand, there was bound to be some crossover. Assiduous footnoting was not in my repertoire, and anyway the need to reference every thought or idea seemed a ridiculous burden on high schoolers just trying to say what they mean. Or trying to say anything at all.

What I was trying to say was: I really liked The Band. Greil Marcus liked them too, and wrote a long essay about them in his somewhat seminal Mystery Train – Images of America in Rock ‘n’ Roll Music. Greil – I’ll call him Greil, for I felt, at least briefly, like we were next of kin, to use a favored Band phrase – wrote beautifully about how The Band’s first two records, Music from Big Pink and The Band, fashioned a way back into America for young adults earnestly riding out the chaos of the late 1960s. Only 16 or 17 when I first read Greil’s essay, I hadn’t thought a lot about why these people would want or need to find a way back into America when they lived there already. Still, I’d had my own taste of alienation, however small-town and focused on some girl or another, and The Band helped me feel more at home too. Clearly, Greil was speaking the truth.

Greil also liked making sweeping statements. Sweeping statements, I’ve learned, allow one to say large, important things. Like: a song either changes utterly the way we see and feel and live in the world, or it fails to reach some not-always-clear moral or aesthetic standard, thereby precipitating its own disasters.

This, I believe, is only a slight exaggeration of Greil’s modus operandi. There’s certainly something exciting in this approach, which gives Greil’s writing the power it sometimes has. When writing about a recording of the song “Who Do You Love,” for example, sung by Ronnie Hawkins backed by The Band in its early stages, he says “It is possibly the most menacing piece of rock ‘n’ roll ever made.”

[embedyt]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ROuimcXJc5E[/embedyt]

Now, by any standard, aesthetic or moral, this is not true, nor was it true in the mid-1970s when Mystery Train was first published. It doesn’t matter much what other instance or rock ‘n’ roll menace comes to mind to counter this statement. I think immediately of the Thirteenth Floor Elevators of the mid-1960s, with the terrifying and exhilarating wail of Roky Erickson poised between heaven and hell – Roky and the rest of the band sounding genuinely on the verge of madness, as indeed one or two of them were.

[embedyt]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gHK9vj0VE7w[/embedyt]

This is, for me, much more menacing – scarier – than Ronnie Hawkins’ and The Band’s “Who Do You Love,” however bracing that recording might be. But, as I’ve said, it doesn’t matter much: Greil had made his point about The Band’s clear potential in its early years and the record’s signifying that something important this way comes.

The essay in question, “Pilgrim’s Progress,” obviously made an impression on my vulnerable, grasping, occasionally desperate teenage mind. How could it not? That someone took any rock ‘n’ roll this seriously, let alone music that was so important to me, turned out to be a lasting, ongoing revelation. And that is why Greil will forever be my friend. This friendship, however, was tested immediately by his shockingly assured-sounding put-down of something else that had impressed me terribly.

~

So this is where this becomes my story, not Greil’s or anyone else’s. Statements about what was good, better or best in The Band’s catalogue meant nothing to me; I hadn’t heard them yet. The painful struggles of artists maintaining both lives and art were barely on the perimeter of my world view. Falling in love, in all innocence, with someone’s art is not wholly an aesthetic choice, is it? There are deeper currents involved, deeper than whether or not you like the way someone draws the human face, in pencil, ink, paint, lyrics, melody, or in the interaction of musical instruments.

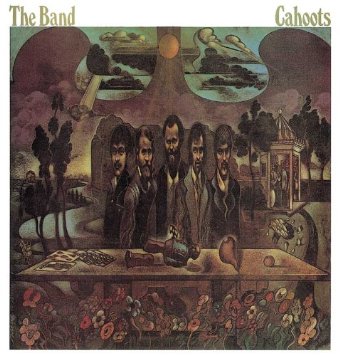

Just by chance, the first proper Band album I’d bought – after playing out my older brother’s copy of Rock of Ages, their much-acclaimed live record – was Cahoots, probably because I liked the name. I still like the name. It started with “Life is a Carnival,” another universally acclaimed Band moment, with its undertow of Band-specific funk supporting an untouchable horn arrangement by New Orleans master Allen Toussaint. This was followed by a fairly jolly, mandolin- and accordion-laden rendition of Dylan’s great “When I Paint My Masterpiece” – surely nothing there to bring offense to a true fan. After that, the record gets weirder, which I’ll address shortly.

[embedyt]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Io9tYdvrFgk[/embedyt]

Living in my open-hearted adolescent dream, I didn’t know the difference between weird and cool (and often still don’t). Therefore I loved Cahoots pretty much top to bottom. The unaccountable appeal of The Band’s three singers, Richard Manuel, Levon Helm and Rick Danko, permeated my bones and made me not only want to hear them but to become them. The music sounded like no one else’s, changing its character from song to song. To make it even better, I was probably the only kid in my class going ape over Cahoots, or listening to it at all, so it was my treasure, a mark of identity when joyful identification was like a line to heaven, or proof of heaven’s existence.

Imagine my sense of betrayal, then, when Greil Marcus turned on The Band, or on me, really, late in his “Pilgrims Progress” essay, to dismiss Cahoots as a failure, a mistake, a load of dung. Though it pains me, I present here the gist of Mr. Marcus’s summation of Cahoots:

“The songs were stiff and the music was constricted; all the humor and drive had gone. On The Band Robbie (Robertson) had breathed life into his characters in one line, and the singers made you care about them; here there were only abstractions and stereotypes, and the singers sounded as if they had no connection to the words they were given…The Band’s ability to present a sense of place was reduced to a humorless presentation of fixed images. The failure of language made even the good ideas of the lyrics unsatisfying – made the truth sound false.”

Enough, Greil. You’ve said enough. When I first read this, I’m sure I had no idea what the fuck he was talking about. Today, many, many years later, when I am surely older than Greil was when he wrote it, I have an inkling. It doesn’t change my feelings about the record, but I have an inkling.

I’ve since read enough, including Levon Helm’s memoir This Wheel’s on Fire, to know that success was in some ways a disaster for the group of friends who made The Band, and were in turn made by it. Drugs and alcohol, of course, along with the uneven distribution of large sums of money, disagreements over who wrote what, compromised friendship, weakening of joint artistic purpose – all of these are part of The Band’s story, and, to be honest, weren’t something I cared to hear about when I was 17 and my heroes were not supposed to have so many issues.

But hear about it I did, not only from brother Greil but from The Band itself. I didn’t know it at the time, but Cahoots wrestles openly with the mess their lives had become. Most telling, most painful, and most easy to ridicule if you’re a critic, is “Last of the Blacksmiths,” which directly (and jarringly) follows the jaunty rendition of “When I Paint My Masterpiece.” The lyric, not fully in control of itself, lurches between descriptions of creative crisis and the fight to maintain something akin to humanity in a world ruled by unrecognizable values: “Have mercy, cried the blacksmith / how you gonna replace human hands / found guilty said the judge / for not being in demand.”

And when the fog rolls away for a moment: “Frozen fingers at the keyboard / could this be the big reward / No answer came.”

[embedyt]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1Xt1rNvxZHA[/embedyt]

These words, coming from the mouth of Richard Manuel, are real enough; having done about half the songwriting on The Band’s first record, Manuel had stopped writing, or at least stopped contributing songs, by the time of Cahoots; he had all but retired, mired in addiction, when his compatriots coaxed him into making another album. But there’s more to the recording than defeat: Manuel’s heartbroken, heartbreaking voice is full, strong, and in command, and the song’s arrangement sounds like nothing else The Band ever attempted, before or after. Ominous open space between bass and piano gives way to what Robbie Robertson called Garth Hudson’s “elephant cry horns” that achieve every bit of the madness of the organ that pushed “Chest Fever” to its limits, back in the Big Pink days.

Despite its unnerving quality and occasionally unmoored lyrics, I’ve always, always loved “Last of the Blacksmiths.” This is the opposite of The Band playing it safe, which is something Greil Marcus lamented in some of The Band’s live performances. Through whatever devices it still had at its disposal, The Band managed to turn its deepest vulnerabilities – artistic and human – into sublimely weird rock ‘n’ roll. And since when is rock ‘n’ roll supposed to be entirely in control of itself anyway? As Yoko Ono once stated so succinctly: “The part that doesn’t fit is me.”

I will mercifully refrain from describing every other song on the record in such detail. There are other pleasures: another beautiful Richard Manuel vocal on Robertson’s sad, sweet “The Moon Struck One,” about a trio of young friends tragically reduced to a duo; “The River Hymn” (which even Greil admitted to liking), as wonderfully churchy and sentimental as The Band ever gets, with Levon Helm, through Robbie’s words, channeling the wise old men they still hoped to grow into: “Son, you ain’t never seen yourself / no crystal mirror / can show it clearer / come over here instead / son, you ain’t never eased yourself / till you laid it down in a river bed”; Rick Danko’s perfect, keening vocal on “Where Do We Go from Here,” whose title was (tellingly) also considered as a title for the album; and the alley-cat lust of “Volcano,” also sung by Danko, with Garth horning it up and Robbie’s trademark spiky guitar strategically inserted whenever everyone else takes a breath.

It’s touching that Robbie Robertson admits, in the liner notes of the re-mastered Cahoots CD, that the naming of the record was a kind of wishful thinking – imagining that the five men might one day be as close as they’d been during those years when they were just a band. Happily, that closeness was again achieved at least musically from time to time. The Band’s next studio record, Moondog Matinee, a collection of covers of rock ‘n’ roll songs they’d played growing up, contains some of their greatest ensemble playing – which is, after all, what they’re known for, and named for.

It’s helpful to remember that most artists don’t proceed in one direction – from good to bad or bad to good. It’s usually much messier and more interesting than that. It’s also helpful to remember that nobody, not Greil Marcus, nor I, nor you have the last word. What has sometimes intimidated impressionable me when reading Greil Marcus and others so apparently sure of themselves is the manner in which they make their pronouncements on the quality of this or that piece of music, or this or that piece of salt water taffy, for that matter – as if there’s nothing more to say about it, leaving no opening for anyone else to walk through. When you’re a teenager, you can half-believe that whatever you read is the final word. Once you’re older, you know that this is not the case. Even as a 17-year-old, I let myself be pushed around only so much. I didn’t, after all, include anything of Greil’s comments on Cahoots in my 12th-grade term paper. In the end, even with the touch of plagiarism, it was my term paper, not his. And I knew what I liked.