I PULLED MY first shift when I turned thirteen. It was at a sad Italian restaurant in a neglected plaza of the sort that would later come to be known as a strip mall. The other stores were a dry cleaner’s, a real estate agency, and a sewing machine repair shop. The restaurant, Luigi’s, was owned by Luigi. He was perpetually irritated, wore thick Buddy Holly glasses, and didn’t speak much English. I made three dollars and twenty five cents an hour as a dishwasher. After each shift Luigi would calculate my pay (always thirteen dollars) on a napkin. He used fractions. Sometimes he’d come up with a figure other than thirteen dollars. I would remind him that I could add. He’d stare, as if trying to decode something in the folds of the crushed velvet curtains, and then grudgingly hand over the cash. Sometimes, just to be an extra hard-on, he paid in change.

Derek and Ray worked in the kitchen. They were both in their twenties, sideburns, smokes behind one ear, usually half-drunk. They constantly threatened to lock me in the walk-in with one of the waitresses and turn off the lights, which for some reason I found terrifying. At least once a shift Derek grabbed a jug of industrial dish soap, held it at crotch level, groaned, and squirted white liquid all over my station. Ray never failed to find it hilarious. Derek was having an affair with the much younger Mrs. Luigi. She would sometimes call on the order line and ask for him in a fake voice. He’d turn away and whisper into the dirty yellow receiver. Even I knew what was going on.

Luigi’s menu was a disinterested slog through the world of canned food, everything more or less a variation on lunchbox Italian—red sauce, white sauce, meatballs, cheese, dishwater spaghetti. In fact, the food was so bad I often turned down the free mid-shift meal even though I was starving. Entrées were served on heavy molded dishes shaped like large clams. The scalloped edges were impossible to wash. I took pride in hammering through pots and cutlery like a veteran dish dog, but when the place got busy I often couldn’t keep up. Ray would repeatedly demand that I extract my thumb from my cherry ass. Eventually Derek would just plunge to the elbow in brackish scum, extract a plate, wipe it on his apron, and serve it up. No one ever complained.

I worked at Luigi’s for over a year. Very few of my other friends had jobs and seemed mystified as to why I bothered. Or how I got my homework done. Or why I always smelled like a combination of sour veal and tomato paste. No doubt my father was pleased to be instilling an early work ethic, but getting the job had been my idea.

And I wanted the job badly.

Because I badly wanted to buy things.

And those things were records.

I guess at some point I just made a pragmatic decision: it was simply too humiliating trying to wheedle the requisite cash out of my parents. I wanted records—many, many more records than they would allow—and the only way to acquire the necessary vinyl was for me to take control of the means of production and distribution.

So I sweated into the metal sink shift after shift, daydreaming about a certain early Black Sabbath UK pressing, or a set of rare Beatles picture discs. When Luigi came grumbling and crotch-fiddling through the kitchen with his cigarette and khakis, lecturing no one in particular about the finer points of being Luigi, I would hum the words to “War Pigs” or “Polythene Pam” under my breath.

My lust for albums had begun a few Christmases earlier, with the gift of a Donald Duck turntable. It was a little plastic suitcase you could fold up and carry around. Donald’s face was molded into the back, while his sleeve and white-gloved hand provided the tone arm and needle cartridge. A speaker was built into the body. I knew Donald wasn’t cool, and wished that it was a Hulk or Fonzie model instead, but I was still in love. It was an interesting gift, because for a long time after receiving it, I owned no records. My parents neglected to follow through with the second half of the turntable equation, so for six months I lugged it around, setting up in various locations around the house and spinning the platter with my finger.

I think it was those first long, lean, vinyl-less months that truly set my jones in motion, and cemented it in place for the following thirty years.

Eventually I saved enough birthday checks and random dollar bills that I was allowed to buy 45s at Caldor’s. At that time Caldor (an east coast department store) still had a little lunch counter with orange vinyl stools and a milkshake machine. It also had a killer record section. While my mother searched for her list and selected the least dirty shopping cart, I raced headlong through Men’s, Women’s, Junior’s, Toys, Sundries, Electronics, and even Candy—to reach the record stacks in the far corner. All the 45s were hung along one wall, gleaming wax circles that dangled in rows from red pegs like a genius art project. I still remember the first platters I ever bought: Paper Lace’s Billy Don’t Be a Hero, Rhythm Heritage’s Theme from S.W.A.T, Sweet’s Ballroom Blitz, Silver Convention’s Fly Robin Fly, Amii Stewart’s Knock on Wood, Foreigner’s Star Rider, and The Temptations’ Funky Music Sho’ ‘Nuff Turns Me On.

I could recite dozens more without pausing, could reel them off like a loaded slam poet long into the night. I remember the titles so vividly because I played them without end while staring at the label art and memorizing production information for some test I was sure would come due in my future life, at the exact moment it was decided whether or not I’d make it as a pro musicologist and freelance repository of recording arcana.

I also remember the following birthday, and the near-orgasmic glee with which I unwrapped a repeatedly asked for Hartzell’s Tote 45, an awesomely hip and well-designed conveyance (and protector) for my elaborately indexed and archived discs.

However, the full flowering of my addiction did not take place until the following summer, when my long-bearded rugby-playing mountain-dude of an uncle inexplicably lost all interest in rock music over the course of what was no doubt a single harrowing weekend. For some reason he decided he just didn’t want his records anymore. Clearly it was a subject better left unspoken, doomed to be buried in the dark loam of family mythology, but as a result a great many records needed to be quickly shed like a stuffed monkey’s paw. Equally mysteriously, instead of selling them or trading them in, he decided to bestow them upon my sister and me.

The gift was monumental. Life-changing. Cataract surgery. Consciousness expansion. Aural freedom. An audience with the Pope or a random Lama. One hot August day I simply awoke a boy and went to bed a man. Walking into the living room where a stack of eighty albums waited on the rug was essentially the equivalent of a West Village painter returning to his garret after a hard day of grubbing for commissions and being presented, gratis, with fifty pounds of pure uncut Turkish hashish. I knew, even before touching the pleasingly architectural stack, that I would soon be transported. And I was right.

My sister and I fought over ownership of the albums for about a week, but she didn’t stand a chance. She pretended to care enough to resist my insistence on a full ownership stake up until someone called and invited her to the next party, at which point they were mine, all mine.

Consider, if you will, the enormity: a musically obsessed thirteen-year-old with suspect taste, ethics, and no real understanding of pop music suddenly locked in his room for months on end with an overheated Donald Duck turntable and pristine copies of The White Album, Abbey Road, Rust Never Sleeps, John Barleycorn Must Die, Tales From Topographic Oceans, Their Satanic Majesty’s Request, Live at Leeds, There’s No Place Like America Today, Surrealistic Pillow, Axis: Bold as Love, Avalon, Al Green Gets Next To You, That’s the Way God Planned It, Songs in the Key of Life, and Let’s Stay Together.

There were also albums by more obscure bands, like The Flock, 10cc, Ten Wheel Drive, Electric Flag, Ten Years After, Mc5, and Gun.

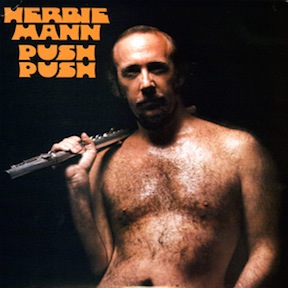

There was even this very disturbing, sexually charged and body wax repudiating classic by Herbie Mann:

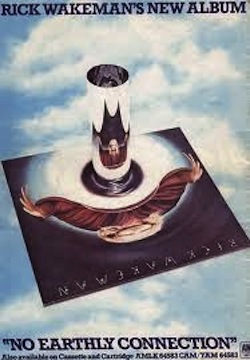

Amongst the varied Yes output was a Rick Wakeman solo album that came with a reflective metal cylinder you taped around a bracket over the sound hole, causing it to spin and make the picture of Rick on the label undulate and morph in just the sort of demonic fashion that might cause any number of impressionable adolescents to suddenly believe in backward masking, not to mention the slow ruination of their Zeppelin albums through attempted divination of the watery secrets lying along the stairway to heaven.

And so, without warning and far too early, I was shoved into the center of a very complex, angry, and drug-fueled sub genre of music that practically dripped with the accumulated bitterness and chaos of the early Seventies. I didn’t know how to process the emotions, let alone the harmonies, so I just absorbed them. Whole. I was dimly aware that thousands of dollars in future therapy awaited, but didn’t care. From that moment forward there was never an instance when I didn’t have music playing at glorious Donald-shattering volumes, a cacophony that resounded off the walls of my tiny room and the interior of my skull. I’d lay on my bed and stare at the ceiling, listening over and over to the mind-blowing weirdness of “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer,” or work on a book report of A Separate Peace while funk-strutting across the carpet to “Nothing from Nothing.”

That fall (after a truly relentless campaign of abject pleading) my parents took me to see Beatlemania in Manhattan. Essentially, it was four guys on stage doing Beatles covers while two hours of black-and-white photography documented everything from the British Invasion to Bull Conner and the Civil Rights movement as projected on a massive screen in the background. After being subjected to images of Kent State and Selma and Bobby Kennedy lying on the kitchen floor of the Ambassador Hotel, I was understandably scarred. But that didn’t stop me from insisting on the playground the following Monday—in the face of universal opposition—that Ringo was a way better drummer than Peter Criss. A group of boys surrounded me and demanded that I take it back. Always one to run from a fight in any other situation, for some reason on this day I would not relent. The much larger, older, and strident Kiss fan Mike Doty took it upon himself to end the argument by punching me in the face. I remember waking up on the ground holding my nose as the gym teacher, Mr. X, told me to stop sniveling, rub dirt on it, and walk it off.

My first experience with unconsciousness taught me two things: one, that Mr. X was not to be trusted, which, apparently, any number of players found out during “private consultations” in the locker room years later. And two: that Mike Doty was right. Peter Criss was better than Ringo. Victors write the history, and makeup defeats skinny ties. Not only was I converted, but from that point forward I was a huge Kiss fan, happy to tell anyone unlucky enough to be cornered all about the genius kick-drum part in “Cold Gin.”

In fact, this is the first actual full-length album I ever bought ($2.99, Caldor’s):

At some point later I acquired pubic hair, left Luigi’s, and moved on to better jobs: busboy, video store clerk, statuary laborer. Money allotted for vinyl got skimmed off by the need for hamburgers, beer, gas, parachute pants, and crappy jewelry for fleeting girlfriends. But most everything else went to my ballooning record collection. I also took to reading audiophile magazines like StereOpus and Audio Alternatives and The Absolute Sound. My Donald Duck turntable had long been replaced by a hand-me-down Soundesign rack unit, but it wasn’t nearly good enough. I knew I was doing my records an unspeakable injustice by playing them through a sound-sieve with measurably crappy response rates and the inability to adjust ohm output, so I convinced my father to co-sign a loan to buy the stereo system of my dreams. We went to the bank together, sat down with a loan officer—who with a phone call verified my busboy status and my weekly income (plus tips) at Beefsteak Charlie’s—and then handed me $800 cash. Borrowing $800 in 1985 was essentially like hitting a loan shark for $30,000 now. Plus the vig. I still can’t believe my father agreed to it. But I did pay it off by the time I graduated. And I still had the receiver until a few years ago, one I lugged in and out of various dorm rooms and squats and crappy apartments around the country over the course of two decades.Not long after, I discovered hardcore. And then Eric Dolphy. And then the Velvet Underground. Suddenly the majority of my collection seemed pointless and insipid. I didn’t want Traffic anymore. Jefferson Airplane was quickly unmasked as a bunch of whiny hippies. I hauled a station wagon full of boxes to Trash American Style, and traded four-hundred classic rock albums for forty Misfits, Minutemen, Fishbone, Pere Ubu, Bad Brains, Meat Puppets, Hüsker Dü, Billie Holiday, Charles Mingus, and Replacements originals. My collection changed, as all collections do. I continued to shed sides I no longer considered worthy, while mining deep veins and whole genres of stuff I couldn’t believe I’d never heard before. I became merciless about dropping dead weight, and yet my overall number continued to grow.

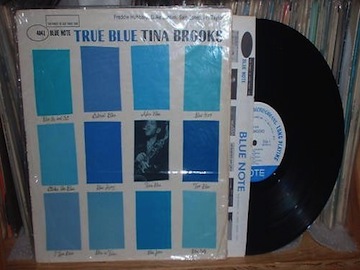

At the height of my indiscriminate and mainlining need, I might have had around 7,000 albums. Now I have maybe nine hundred. Rock bottom came quick. First it was CDs, and then torrents. The bitch of convenience. I just couldn’t carry that payload up another set of stairs. When we moved four years ago, I culled like a cruel rancher, ridding the herd of everything that wasn’t an original pressing or something so nostalgic and vital that there was no way I could part with it. Eighty percent of what remains is 50’s and 60’s jazz. The rest is obscure funk. Everything else is a soulless mp3 haunting my computer. All the punk stuff is long gone (sold on eBay at an outrageous profit.) The blues are mostly gone. The rock is gone. The honkeytonk is gone. The yard sale sludge is gone. The Leonard Nimoy album is gone.

All that remains, in this moment of clarity, is hard bop and raw memories.

![Kiss.Destroyer.cover[1]-001](https://www.theweeklings.com/wp-content/uploads/Kiss.Destroyer.cover1-001.jpg)

At fifteen, I stole $20 or $30 from a stranger’s purse in order to fund my own record-buying habit. I felt guilty at the time, and feel worse about it now, but anyway, you at least worked to afford your own habit.

Lots of evocative imagery here. I’ve already mentioned, elsewhere, “cataract surgery,” but I’m curious as to the smell of “sour veal,” though not so curious that I would seek it out.

Oh, and I believe you were upholding a family tradition by divesting yourself of the music of your youth. May you the spirit of D. Boon haunt you.

Typo! Where’s the goddamn edit function?

It is true, Duke, that you have no need for the actual sensory knowledge of sour veal to be introduced into your life at this late date.

Also true about our genetic familial need to shed vinyl, but divesting in my case only meant converting to binary code with lousy bass response and then storing on a hard drive.

The spirit of D. Boone haunts either way. So does Project Mersh.

“Or how I got my homework done”

I do not agree, read that:

http://dailytrojan.com/2013/04/08/60s-style-takes-over-runway/

Best regards, Merlene