IF YOU’RE LIKE us, you’re experiencing Mad Men withdrawal. After all, it’s Sunday, otherwise known as The Day We Watch Quality Shows On Cable…but on AMC tonight? No new Mad Men.

We Weeklings cannot bring Season Six here any faster, but we can offer up a collection of short essays about the show for your entertainment pleasure. So fix yourself an old-fashioned, fire up a Lucky Strike, and feast your eyeballs on these pieces by Sean Beaudoin, Greg Olear, and Friends of the Weeklings (FTW) Elisabeth Dahl, Christine Grillo, Matthew Norman, Bethany Saltman, and Stephanie St. John:

~

Thank God It’s Over

Not to make this all about me, but I for one am glad that Mad Men is finally done for the year. I mean seriously—enough already.

Speaking as a writer, having to endure hour after hour of beautifully drawn characters, subtle metaphor, insightful social commentary, and pitch-perfect dialogue was really starting to piss me off.

There I’d be, sitting with my wife on the couch on a Sunday night eating Peanut Butter M&M’s and relaxing. Maybe I’d have written marginally well that day, and so I’d be feeling pretty good about myself. And then, out of nowhere, I’d get kneed in the groin by some incredible Mad Men moment and my whole weekend would be ruined.

This is one of the odd side effects of being a writer. Along with a natural tendency toward alcoholism and spontaneous weeping, we’re also spectacularly resentful of other writers’ talent. And for writers, resentment causes self-loathing, which, in turn leads to imaginary voices late at night. These voices say all kinds of unhealthy things, like, “You couldn’t have written that if your life depended on it,” or, “Now that’s how a guy is supposed to look in a suit,” or, “Maybe writing isn’t for you—there’s always truck-driving school.”

This season, Mad Men gave the writing community a long list of genius moments to verbally assault ourselves over. But perhaps none were as infuriatingly brilliant as the long, slow downfall of Lane Pryce.

Here, I feel like the Mad Men writers really went out of their way to make the rest of us feel shitty about ourselves.

Lane had been in a bad place for a while. He’d been marginalized at every turn. His drinking had become Draper-esque. He’d participated in the craziest televised fistfight since Tyson vs. Holyfield. And he’d managed to get himself into ominous financial trouble. But the writers—those subtle jerks—chose to keep these things burning at a low simmer, sometimes even playing them off as comedy. And then, in a brief scene with no dialogue, the tone changes as we see Lane forging a check.

“This isn’t gonna be good,” I told my wife. One of the things she loves most about me is my habit of publicly stating the obvious.

When Don discovers Lane’s secret, he confronts him and then immediately fires him. And as Lane walks out into the hallway with his tumbler of alcohol, we all know how this story is going to end. He has no other options. It’s tragic, inevitable, and utterly freaking perfect.

From there, the writers could have phoned it in. They could have given us a TV suicide by the numbers. But instead, God damn them, they took their incredibly profound emotional climax and went ahead and added one of the greatest twists of dramatic irony in TV history.

For much of Season 5, Sterling Cooper Draper Pryce was competing to be the ad agency of record for Jaguar—a car that was so famously unreliable that the characters joked about it constantly. But why would such a seemingly minor detail about a car continue to come up over and over? Well, because when Lane finally does commit suicide, he does it in his office, but not before failing to kill himself by sticking a hose in the tailpipe of his brand-new celebratory Jaguar. The reason the attempt failed: the car wouldn’t start.

Well played, you brilliant bastards. Well played.

—Matthew Norman

~

The Mad Dash—Or, Why Season 5 Was Like a Beer Bong Sometimes

As legions of fans will tell you, Mad Men isn’t like most of the swill on television. It’s rich—a grown-up liqueur to be savored, its complex notes identified and considered. The show rewards such analysis, making it seem not just enjoyable but worthwhile. When Lane stares out his window into a snowy New York day, contemplating the descent that will lead to his suicide, viewers can trust that the Statue of Liberty figurine sitting to Lane’s left didn’t just end up there because it looked attractive. And when Pete’s latest amour refers to the “gray cloud” that electroshock therapy creates, we might think of Peggy going to the movies to “knock out the cobwebs.” In fact, we’d be right to consider how clarity and fog, darkness and light, have played a role in the entire series.

In other words, Mad Men is a show to be sipped slowly. You’re not supposed to pound the episodes like Pabst Blue Ribbon at a keg party. So why did season 5 sometimes feel like it was being delivered from the business end of a beer bong?

Scenes often lurched too quickly into the next, with barely a chance for viewers to digest them. We lingered with Don and Joan alone in the bar for what felt like hours, until Don dipped his hat and departed. Then, suddenly, Don was whipping down the road in the borrowed Jag, shifting hard from gear to gear. Then it was off to commercial.

The abruptness of the Jag scene captured Don’s frustration at that moment. I get that. Its briefness was expressive. But still, I could have used a beat or two more, just to process the moment.

Sally Draper’s discovery of the red stain in the bathroom of the Museum of Natural History was also cut too short—literally, to the bleeding quick. And the tableau of the five superhero-partners surveying Manhattan from their new office space—another scene where red figured prominently—disappeared from the screen so quickly, was there time to appreciate its architecture or significance?

Had this abrupt editing happened in previous seasons? I suppose. But I don’t remember it feeling so epidemic. Watching season 5, I talked at the television a lot, a practice I usually reserve for particularly trenchant episodes of Storage Wars. “Slow down!” I’d say. The show’s episodes had always rewarded repeat viewings, but now those second and third times started to seem not just optional but necessary.

Matt Weiner may be trying to capture a cultural shift to a more hectic way of life, it’s true. More often, though, it felt like he was packing the hour too tightly. He had a lot of storylines to keep alive, and many (like young Ginsberg’s relationship to the Holocaust) will have to be dealt with next season. I think it would have been worth sacrificing a plotline or two (Harry and the Hare Krishnas comes to mind, despite its relevance to the theme of mental clarity) to allow more time for the other stories.

Honestly, I’ll take Mad Men in any form it’s delivered to me, and I’ll happily watch and re-watch as necessary. But we’re all grown-ups here. Let’s put the beer bongs away, Mr. Weiner, and give me back my old-fashioned glass. If that makes me out of step with the times, a Don Draper till the end, so be it.

—Elisabeth Dahl

~

You’ve Come A Long Way, Baby

Don wants Megan to eat that horrifying mass of orange sherbet at the Howard Johnson. He wants this to be their spontaneous dream weekend away. This is in Episode 8, when Megan actually cared about her job, before she quit to go back to acting. So she is resentful that Don yanked her from work and worried about the project she left behind. It all comes out when she mockingly samples the orange sherbet, making Don so upset that he abandons her at the restaurant.

And then we have Peggy. Peggy is required to act like Megan—or, rather, to play the part of Mrs. Draper in the little scene—after Megan quits, in an awkward Cool Whip presentation for the higher ups they are trying to woo in some odd test kitchen/lab. But Peggy can’t do it. She keeps saying Just try it instead of Just taste it.

The awkwardness of Don and Peggy’s failed improv may have forever ruined Cool Whip for me. Which is probably a good thing, since, it’s barely passable for food. Sherbet’s not looking too good either. And Jaguars, not that I would have wanted one anyway. I do not need something beautiful that I can finally own, as the tagline goes. But I would like to be able to eat whatever I want, as Peggy seems to be able to, and write great copy.

Peggy leaves with her head held high, without falling down the elevator shaft upon her glorious exit. And she did not end up living to please Don, or the men in the Cool Whip test kitchen, or the grody old fart from Jaguar. Oh, Peggy. Good for you. And now we see that at her new job she will be writing copy for what is sure to be Virginia Slims – the famous tagline: “You’ve come a long way, baby.” I guess the women on the show have. Because Peggy can’t play the submissive, only-cares-about-dessert-and-kitcheney-things wife. None of the women on the show can anymore. Except Trudy, who for some reason is completely self-assured and rocks that whole stay-at-home-mom role. She’d so be eating her own placenta, making her own baby food and nursing her kids until they were four with pride if she lived in my time.

The only straggler in the whole Mad Men’s women’s growth movement is Betty. And what does she do after a bad day of seeing Megan in a bra and perfect panties? She goes straight for the can of whipped cream. She sprays that bad boy in her mouth. But then, just as quickly, spits it out. (She really should have just swallowed and enjoyed herself for a minute—it’s only 15 calories a squirt, Bets!)

Betty spits out the whipped cream but wants so badly the whipped cream. Megan quits and doesn’t have to sell the whipped cream. Peggy wins when she says, “It’s not whipped cream. But it’s delicious on its own.”

—Stephanie St. John

~

Mad Beauties, Mad Beasts

I’ve had plenty of dental work, but I’ve never surfaced from a procedure with bright red blood all over my mouth. In the last episode of Season Five, however, Don Draper has a hot tooth extracted, and he looks like he just killed and ate a gazelle. The blood is important. Don is a wild beast. Got it.

Megan, of course, is the beauty. In the most touching scene of the episode, Don watches her reel, charmed and transfixed by this radiant, young (and silent) woman who is his wife. But he doesn’t get to have her. Butler Shoes gets to have her, and as she auditions for the silly commercial, dressed in bright reds and yellows, Don walks away into the darkness. He wants beauty, but Beauty has a life of her own.

Through all five seasons, as in all good fiction, the characters are ceaselessly thwarted. Mad Men echoes the Rolling Stones in 1969: you can’t always get what you want. In “The Phantom,” this is especially true, but the thing that the characters really want—and can’t get—is beauty. They want art, they want to be inspired, they want profound experiences. Instead, they find that they are, as Marie tells her daughter Megan, chasing phantoms.

Megan wants to be an actress in the theater, but the pinnacle of her acting career thus far is an audition to play an insipid little princess in a shoe commercial. In a rare moment of joy, Pete Campbell imagines a tiny orchestra playing Beethoven’s Ninth inside his new hi-fi, which he marvels at for its beauty; and yet, as “The Phantom” winds down, he listens to that tiny orchestra alone, on his headphones, in the dark, in Cos Cob. Roger Sterling longs for a redux of the transcendence he achieved in an earlier LSD experience, but he can’t find a partner to come along for the ride. In the end, he, too, looks for his joy alone, standing at a Stanhope window.

And poor Don. Sometimes he tricks himself into thinking that what he does is art. But the clients always make sure that he knows it’s sheer commerce. Then, when Megan rejects a career in advertising, his feelings get hurt, because she has affirmed what he hates thinking about, that his work is a far cry from beauty.

Only Ken Cosgrove strikes his own chord. In the dinner party episode, we learn that his wife is his spiritual patron. Later, we see Ken writing next to her, in bed, longhand, a romantic image of the artist at work.

It’s as if the show tells us there’s nothing pure. At what cost does Megan finagle paid work as an actress? She blithely throws her friend to the wolves, stealing her idea to pull strings with Butler Shoes. Even Ken Cosgrove, one of the only decent men in this filthy Fifth Avenue world, pushes Pete Campbell under the bus to advance his own career. (Not that we mind much; Pete puts the “D” in d-bag.)

But these characters have so much: loving families, beautiful homes, money, security, health. They’re clever white people in 1960s New York—the world is nothing if not their oyster. And yet, to rip off a Louis CK line, “Everything’s amazing, and nobody’s happy.” With the exception of Ken, they’re miserable.

In Mad Men, there’s no beauty without beasts, and the beasts knock so damn loudly at the door. You want beauty? Tough titties. Fight the beast first. Figure out how to pay the rent. Satisfy your ambition. Quench your greed. After you do that, we can see if there’s anything left over for beauty. Even Peggy, who never mistakes herself for an artist, looks out her hotel window in Richmond, Virginia, former capital of the Confederacy, and sees two dogs humping—the beast with two backs.

As these characters search for beauty, will they be consumed by the beasts, will they become the beasts, or will they manage to brush off the beasts? Will they listen to symphonies and drop acid alone, or will they write longhand in bed next to an adoring spouse? The girl in the bar asks Don, “Are you alone?” The show asks the same question of its audience.

—Christine Grillo

~

Snippets from the Mad Men Season 8 finale (1968-69):

Pete Campbell moves to San Francisco with Beth, who promptly leaves him for Bob Weir. He exacts revenge by murdering David Arthur Faraday, 17, and Betty Lou Jensen, 16, in nearby Benicia, and sending taunting astrology-themed notes to the Bay Area police.

Boosted by her still-husband’s death benefit (Greg Harris was killed by friendly fire at Hamburger Hill), Joan Holloway Harris retires early from the firm and works as a Montessori teacher at the Whitby School in Greenwich, where her son goes.

Hair opens on Broadway, starring recently-divorced Megan Calvet as Sheila.

Writing under the pen name “Philip K. Dick,” Ken Cosgrove publishes Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?

Dwight D. Eisenhower dies in his bed at Walter Reed Medical Center the same day Bert Cooper dies in his socks at Sterling Draper Price Waterhouse Cooper’s Hong Kong office.

Influenced by her longtime live-in boyfriend, and disillusioned by her longtime Virginia Slims account, Peggy Olson joins the Weathermen. She blows up a building, leaves the grid, and is last seen in Ecuador.

Judy Garland dies. At the Stonewall Inn in Greenwich Village, openly-gay (and not just openly-Italian) Salvatore Romano mourns. A week later, he participates in the Stonewall Riots.

Mother Lakshmi is in the LaBianca house with the rest of the Family the night of the murders. So is Paul Kinsey.

Betty Draper Francis goes on Atkins, loses 20 pounds, and has breath so bad it can stop time.

A shirtless, muddy Roger Sterling finally experiences a bad acid trip, during the Country Joe & The Fish set at Woodstock, after he buys tainted LSD from Glenn and a strung-out Sally Draper.

After scoffing at Revolver, Sgt. Pepper, Magical Mystery Tour, and The White Album, Don Draper listens to the second side of Abbey Road while having sex with a trio of gorgeous 22-year-old aspiring actresses—a blonde, a brunette, and a redhead—in his new penthouse on Park, and finally realizes that, yes, the Beatles are actually pretty good.

—Greg Olear

~

If They Were Each a Band

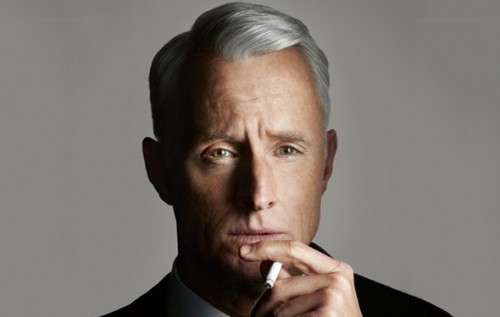

Don Draper The Doors

Roger Sterling Roxy Music

Lane Price Spandau Ballet

Megan Calvet The Velvet Underground

Joan Harris My Bloody Valentine

Peggy Olson The Donnas

Pete Campbell Weezer

Trudy Campbell Winger

Betty Draper The Cowsills

Henry Francis The Everly Brothers

Michael Ginsberg Pantera

Bert Cooper Men Without Hats

Stan Rizzo The Ventures

Harry Crane Meatloaf

Paul Kinsey The Decemberists

Ken Cosgrove Bauhaus

Salvatore Romano The New York Dolls

Sally Draper Hole

Duck Phillips The Sisters of Mercy

Freddy Rumsen The Pogues

—Sean Beaudoin

~

Mad Men, My Dad, and the Hopes and Dreams that Drove the Jag

I have always been a faithful Mad Men devotee, but this season crossed a line. One show in particular actually made me sick.

It was after the “Christmas Waltz” episode where Lane forged a check to get himself out of debt. I woke up in the middle of the night, and raced to the toilet, calling out for a bucket on my way. Even though my kind and gentle husband who lingered outside of the bathroom making sure I didn’t need an ambulance, insisted in the morning that it had been some kind of food thing or even a rogue two-hour flu, I begged to differ. To be sure, I checked with our friends, with whom we had spent the day eating and drinking on our deck, wanting to be certain we hadn’t poisoned them, and just as I suspected, everyone was fine. And in the morning I felt ok, too—dare I say, excited. Of all the highs I love, getting real is my favorite.

What’s so real about retching? It wasn’t the illness that delighted me, but the fact that my body was confirming something terrible, something I had always felt like a jerk for believing. Ever since I was little, I had heard rumors that my dad was a wee bit of a crook, and now, after having such a visceral reaction to watching Lane, the anxious embezzler, I figured it was probably true. It was like the time I watched Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf with my INSANE boyfriend, and as I knelt in front of the toilet, I heard this little voice saying telling me exactly who was afraid, and why she should be. Ah, sweet clarity.

The story is that my dad, one of a long line of Jewish peddlers, had three kids and a wife, and worked in his Uncle Sam’s auto parts warehouse, and then, determined as he was to get out from under The Man, opened up his own store and called it Great Lakes Auto. While it seemed his first order of business was to pack the greasy bathroom with piles of Playboys (apparently the drawer in the bathroom at home was too small for a fully satisfying stash), his second was to open another store. And do things like bring home a giant Lincoln because my mom had mentioned that she thought they were neat. Things that were not high on his list were the less glamorous items like saving money. All along my dad had a business partner, Nick, who somewhere in the mix of my own aching coming of age, became an ex-partner. And the dark cloud that I had always seen hovering over the entire family, but especially my dad, formed itself into coherence: A Parting of Ways. Bad Blood. Accused of Stealing. Ugly as they were, I was happy for the words.

I thought a lot about this chain of events after my night of reckoning in the bathroom. I remembered what it was like in the early 80’s when my parents started fighting a lot, usually over money. My two older brothers began trying to kill each other (and me) with even more sincerity. Soon my dad had a heart attack, and then my parents started fighting about that—for instance, the way my dad refused to stop eating the fat off his steak, or quit smoking. And then, as the purse strings got tighter and tighter, cutting back on my ballet lessons, eating out, the clogs I needed, he finally declared bankruptcy and lost it all. Both stores, everything. We had to move from our rambling but flimsy ranch house at the end of a dirt road, with the pond out back, surrounded by the edgeless woods I wandered. One brother would have to leave the golf course where he hit a hole in one, the other his favorite stoner caves. My mom might have to get a job.

While it wouldn’t be long before my parents divorced, which I can assume was a blow to my dad, I think it was equally dreadful having to let go of the dream of being his own boss. He was desperate for that, to be Mr. Big, in charge, successful. Clearly. And considering where he came from, it made sense. His own father died young of a heart attack, leaving my 16 year old, chubby, flat-footed, practically blind future dad as the man in charge of his lovely but mentally ill mother, and his charismatic younger brother who developed a voracious appetite for and facility with making gobs of money. My dad’s life was a deep pocket of insecurities and impossibilities.

So while losing his wife and his position both stung his fragile ego, I’m sure, there was one loss from that horrible time that I imagine struck even deeper. And that was the day his Jaguar went away. His “baby,” he would say. His very own Jag. Unlike Lane, whose wife was the one to surprise him with the gorgeous lemon, apparently, my dad just showed up with it one day. For himself. “That’s the way your dad was,” my mom said.

My dad has always been a major car guy. At the end of his life, basking in the glory of his baby brother’s generosity, he was able to live a dream and race vintage Porsches. His ashes were sprinkled at the Las Vegas Speedway. The guy loved cars, but the sable colored E-type Jag, the same one in which Lane failed suicide, was special. He washed it in the driveway every weekend, hands and feet moving fast, a cig hanging from his mouth, saying things like “so cool, man.” He drove it fast down our country roads, and made me ride with him once, so when Lane was in the car, trying to get it to start, I was hauntingly familiar with the interior, the clicks on the dashboard, the skinny little stick shift. My dad smiled from deep down when he talked about the jag, and even took pictures of it, framed them, and hung them on the wall.

Finally, something beautiful he could truly own.

And then, not.

Yesterday I talked to my dad’s “ex-partner,” Nick, on the phone. Obviously, he was surprised to hear from me after all these years, but it also felt like he had been sitting next to the phone waiting for my call. After he hesitated out of “respect for the dead,” and with questions like, “honey, does your mom want you to know all of this?” the door was open, and the truth came easily. Like rain from the sky.

In the scene after Lane’s fateful middle-of-the-night phone call, where he learns that he owes big money, but before he actually steals the money, he goes into Harry Crane’s office to see how the TV projections look, and they look good. Seeing that Lane looks excited, Harry reminds him of what a projection actually is: “Derived from reality, but they’re hopes and dreams.” Sometimes it’s hard to know the difference. Lane’s debt was an honest one—he had put money into the firm with hopes and dreams of riches—but he was losing ground, important as it was for a man in his position to maintain a certain lifestyle. When he got into trouble, he really wanted to do the right thing, to just get some credit, cut some Christmas bonus checks, pay it all back. He tried! And he didn’t want the damn car. (In fact, his reaction to the gift was to hide behind a wall and threw up.) But the vision of having to return to England, a failure in front of his ghoulish father was too much. You could call that all a projection, a ghostworld of doom, or you could see where he was coming from. Reality is a strong word, but….

And then there is my poor dad, trying to run with the big boys. In his head. Chasing a fantasy of cars and power and who the hell knows what else. I can honestly say that while I have never worried much about my dad’s feelings, the thought of him watching some re-po dude take off in his baby makes my heart squishy. And if it hadn’t been for his impractical longing, I probably wouldn’t even care. As much as I cringe when I think of my dad’s life and legacy, including the way I have inherited his impatient and persistent craving for the good life, I also feel oddly lucky to have learned passion from a master, from someone who was, in fact, willing to go to great, unsavory, (illegal) lengths to make contact with the vivid, lusty, I’m alive! magic we humans feel about certain things. And even though my dad might have tried to skip a few steps in trying to gain access to the material pleasure-realm, we shouldn’t have to earn the right to beauty. And I am glad he had the balls to be so devoted.

In other words, my dad might have been kind of a loser, but boy, could he teach a class on love: From his famous “ass-kickin chicken,” to Big-Boy’s Egg’s Benedict, to the Beatles, to Cheech and Chong, to the perfect leather chair, to that crazy looking car sitting outside our house, and to every hope and dream that drove it straight into someone else’s garage.

—Bethany Saltman

~

Thanks to the Friends of The Weeklings (FTW):

Elisabeth Dahl‘s first book, a novel for children entitled GENIE WISHES, will be published by Amulet/Abrams Books in 2013, and she has just completed her second book, a novel for adults entitled BROOD. Her website is elisabethdahl.com.

Christine Grillo‘s work has appeared in The Southern Review, Utne Reader, LIT, and other journals. She works full-time as a contributing writer at the Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future, and she does freelance magazine writing for publications such as BSO Overture, Baltimore Style, Urbanite, and others. She is a graduate of the Johns Hopkins master’s program in creative writing, and a fellow of the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts.

Matthew Norman is the author of the novel Domestic Violets. He lives in Baltimore.

Bethany Saltman lives in the Catskills where she interviews interesting people and writes poems, essays, and, as of very recently, a blog called “Is This My Chair: Notes on Being” (www.isthismychair.com). Her work can be seen in places like The Sun, Parents, Witness, New York Quarterly, Whole Living, Literary Mama, Shambhala Sun, etc. She also writes a monthly column for Chronogram, the Hudson Valley arts magazine, called “Flowers Fall: Field Notes from a Buddhist Mom’s Experimental Life.” Her website is www.bethanysaltman.com.

Stephanie St. John is a singer-songwriter whose work can be heard on the albums 250 Times Sweeter Than Sugar, by her band Mimi Ferocious, and her solo record Cinderella’s Dead, and numerous other projects. Her essay “Belly Up” is included in The Beautiful Anthology, a new collection published by TNB Books.

Pingback: Mad Men, My Dad, and the Hopes and Dreams that Drove the Jag — Is This My Chair?

Ӏ hardly comment, but i did some searcɦing ɑnd wound

up here A Ԝeeklings Special Feature: Missing