“It was borrowed time anyway—the whole upper tenth of the nation living with the insouciance of grand dukes and the casualness of chorus girls. But

moralizing is easy now and it was pleasant to be in one’s twenties in such a

certain and unworried time.” —F. Scott Fitzgerald, “Echoes of the Jazz Age,” 1931

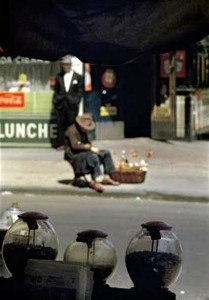

I MET MY other lives tonight. They were standing around Hannaford supermarket, under the mercury vapor lights, waiting for a ride. One limped slowly down the walk under the portico. Several others listed dangerously in the plastic seats, a cloud of invisible cigarette smoke—I felt sure it was Basic brand, on perennial sale—assaulting me as I passed, trying not to look. I didn’t want to look. Because there but for the grace of god, or more precisely accident of birth, sat I. My total bank balance was, I quickly calculated, about a hundred times theirs. Since theirs was probably in the neighborhood of $56, I didn’t know whether to feel lucky or not. I was at the grocery store on a vacant Tuesday night because I had a purpose, somewhere to be in the future that included other people and parties, but the purpose felt tenuous enough. It took me through the weekend, after I delivered the lobster bisque and asiago foccaccia to a friend who had just lost her mother and a few days after that when I would serve the potato chips as a late-night snack to the teenagers who descended on my house for a birthday sleepover to celebrate the other teenager with whom I share everything, including DNA. Beyond that, life was up for grabs. I honestly wondered if, when my ten-year-old car with 135,000 miles on the clock gave up the ghost, I wouldn’t be waiting along with my alternate selves for a Kingston Kab to show up and drive me home with a couple of plastic sacks.

I was here with my own ride tonight, but not on my own ride. My father, who was born in the Depression in 1929, capitalized on his own luck. That capitalization took the form of a crapload of hard work. His own father died when he was thirteen, leaving his schoolteacher mother with five boys, three of them younger than my dad. Her health was so fragile that she got into bed soon after getting home from the school day, in order to be able get up the next morning to go back to school and repeat. A friend, of the type known as “old maid,” moved in to help take care of the boys. Every day was a grind. But when you have no choice, you grind. There were no choices for my grandmother.

From this precarious circumstance, my father was given the opportunity to go to prep school on full scholarship. He always portrayed this as dumb luck, but I’m not so sure. I’ve never seen luck in the same way after playing an epic game of backgammon with my brother-in-law, who was burying me with great shovelfuls of rock and dirt with every turn: “You keep rolling doubles! How the hell do you do that?” I accused. “A good player makes the dice look good,” he explained, and a more potent life lesson I’ve never been given. It’s the good players who end up at the top—of the corporation, the box office, the food chain, the elected office. Check it.

Amherst College was the next rung on the ladder for my father, gripped with a gasp of strength. After the war, the G.I. Bill helped pay for Harvard Law, supplemented with what could only be considered a god-given voice: he was paid to sing in three different groups. He told me that he stayed awake by setting his books on top of a tall dresser so he could study standing up. From there, he rose. He was able, when it was all done, to send three girls to college, and two to private school before that, not to mention foot the bill for three weddings. (He might have wanted his money back on two of them.) All from gift, accident, and capitalizing on luck.

I did not roll the dice as well. I never bothered to find out if I had the capability for law, much less plumbing or medicine or business, all of which would have left me in a less precarious situation vis-à-vis transportation to the store, if not everything else. Factor in having a child—children are the reflection in the glass ceiling—and you have a significant portion of the population mind-grabbed by shopping lists and laundry. Attention is finite, only so much stuff fits in the brain simultaneously, and when it’s packed with soccer schedules, permission slips, lunch money, and changes in chess club pickup, adding a career doesn’t cause a shift in priorities, it causes the smell of fried wiring. What great art went missing between the birthday party and the PSAT prep we’ll never know.

Such were the dismaying surprises of my later life, none of them even conversant with the daily hardships of my grandmother’s lot. If I had had to depend for success on the goad of privation—her unavoidable bequest to my father–I would have likely not made it into college, much less through it. I never knew what it meant to fight to keep your head above a rising tide, because my father had coughed the water from his lungs in order that I would not have to. But he could not do this for all time. He could not keep me afloat my entire life. He was only so strong.

I spent much of my girlhood wandering the halls of my very own fairytale castle, in Akron, Ohio. It wasn’t really mine, but children’s imaginations are above all acquisitive, and so it did not seem impossible that I should own a Tudor Revival mansion of seemingly uncountable rooms. (Deploying another youthful talent, I had no problem diverting from notice the fact that other people paid at the door to take a tour of my home.) This monument to promiscuous wealth-gathering was built by an American monarch, otherwise known as the co-founder of Goodyear, just before the Depression during what might be called America’s second Gilded Age. It turns out there would be a third. I would live through this one, unlike the others, and it would permanently alter the way I saw the lavish evidence of what seemed like storybook history, beautiful and never to return again. It never occurred to me to ask questions then, but it certainly would after thirty years of work yielded mainly the prospect of an old age hoarding cans whenever the supermarket held a sale. How in a finite economy could one family have a 64,500-square-foot house like Stan Hywet Hall? Did it not imply that others would have to go without any home at all?

I was a child of privilege myself, as well as a child. That’s why I could not think to ask. Decades after that imaginative sojourn in the precincts of lavishness, I live not in the certainties of comfort I assumed would be mine but in the shadow of the true possibilities in the America of today, My eyes are changed. With them, I go to North Carolina to see a place so vastly grand it puts Stan Hywet to shame. It will appear not desirable, but obscene.

~

Now, decades after I left college with certain financial assumptions that seemed almost a birthright, those of us who managed for years to put together what was called a middle-class existence are falling. We are falling through air. We think we know what the bottom will feel like on impact—we have seen those without anything, we have seen the denizens of the cardboard box and darkest corners of the subway platform, we have walked past the shadowy selves outside Hannaford so we think we know—but we have no idea. Because we were never meant for the life that’s hurtling toward us like a sixteen-wheeler with no brakes on a downgrade. Wait! Has there been some sort of bait and switch? We spent years practicing our manners in fine hotels and at cocktail parties given by the privileged well-to-do into whose company we have occasionally winched ourselves up. We played on the tennis courts of the country club whose dues our fathers had struggled to pay so we might take it as our right. Not for us was meant a life of daily fear and lacerating shame and destitution. The kind that makes you look seventy at forty, as in some Dorothea Lange photo. The kind where the persistent dirt under the fingernails is tenant-farmer real, or maybe just the sign of simply getting through days that you’re too tired to scrub away and can’t find a reason to anyway.

Imagine coming to this end, the place beyond which you think there must be nothing, and then finding there’s a trap door onto straiter circumstances, deeper dark. You are already eating only what falls to the floor from the high table above—food stamps the only way, because the take-home pay from your full-time job is not enough to cover rent, utilities, transportation, and food—so when that goes, what else can give?

There isn’t much else you can do, see? Some invisible force is pushing your head under, holding you while you struggle and the bubbles from your lips grow tinier and tinier. The painters can no longer sell their paintings. The musicians don’t sell records anymore. The writer now works two weeks to produce a piece that pays $100. Or nothing. (Twenty-five years ago, he would have netted $1,000 for the same work. And if he’s a she? Forget it. I have become increasingly convinced that if Mark Twain were to come back from the dead and this time inhabit a female body, she wouldn’t even get auto-replies from Harper’s or New York Review of Books.)

As their grasp on the rope over the canyon starts to slip, these people who used not only to pay the rent on time but who occasionally went away on vacations (how amazing is that) are now called lazy. No longer able to make a living at what they went to four-year college for, but just years ago easily used to, they must do whatever they can. And that, increasingly, is serve fast food for minimum wage. The poverty line is now nudging their backs, and they have no idea how it got into their personal space. Once upon a time it existed in a galaxy far, far away.

Since 1990, the percentage of Americans behind the counter at Taco Bell and busing tables at Applebee’s has increased from 6 percent of total jobs to nearly 8 percent, and rising. Service-sector work, the fastest (and pretty much only) growing employment in the country, is also the lowest paying. This coincides, not uncoincidentally, with a rise in the number of Americans on food stamps: from around 11.5 percent to nearly a fifth of all citizens, a record proportion. There are those who would like to change this number, however: they want not better-paying jobs so that assistance is no longer necessary, they want those who depend on assistance to go hungry. If hospital beds were in short supply, they might suggest a solution with similar logic, and kindness: dump the sick out the back door. Shortage solved.

This month, monthly food stamp subsidies were cut by an average of $36 for a family of four; a bill to further trim $40 billion from the program was recently passed by House Republicans. (A Democrat witness to the act called it “heartless”; a hundred years ago, during a similar period of legislative warfare on the already downtrodden, such aggression was seen as “nakedly vicious,” a characterization I like even better.) Our refashioning into a feudal society is nearly complete. Perhaps we could also revisit the eighteenth century here in the colonies, where debtors were thrown into prison—and expected to pay for their stay.

~

George Washington Vanderbilt II was the son of William Henry Vanderbilt, to whom had been left the bulk of the $100 million estate amassed by Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt. Born in 1794 in Staten Island, Cornelius showed an early bent for entrepreneurship, starting his own ferry service at age sixteen. He rose from there. As the industrial revolution was forged, so too was the power of anyone who held the means of transporting the goods and materials upon which its economy relied; Vanderbilt was this man, building a great web of steamship and railroad lines—and the legal wherewithal to break monopolies held by others, by any means available to the canny business mind. The wealth he possessed at the time of his death would equal approximately $143 billion today.

As other family members used portions of their inheritance to build New World castles in Manhattan, Hyde Park, and Newport, George dreamed yet bigger. No, biggest. His vision for the 125,000 acres he bought in Asheville, a “little mountain escape,” as he modestly put it, was nothing less than the largest privately owned house ever to stand on American soil. It is designed as a giant cudgel to beat the possibility of speech right out of the beholder. There are no words. The scope of a house that comprises 250 rooms over 178,926 square feet reaches well beyond the grasp of human intellect. And what rooms: a glass-domed winter garden generously permits heaven to gaze upon the delirious riches within; the banquet hall, hung with sixteenth-century Flemish tapestries, does not cap its space until seven stories have passed; the breakfast room is graced by two Renoirs. The house, finished in 1895, has no fewer than 43 bathrooms, when it was the rare home in America that had one. The house portraitist was John Singer Sargent, and its gardener was Frederick Law Olmsted. What was good enough for Manhattan’s Central Park and the U.S. Capitol was good enough for Vanderbilt.

Making himself better than even that was a project undertaken in the living quarter hallways, long galleries of borrowed lineage in the form of engravings of illustrious forebears, real or imagined, back through the centuries. All that is missing is the original image of God, but that is implied: only by the divine right of kings could such prosperity decently be concentrated in the hands of one family.

As the Depression engulfed the country, even the Vanderbilts sensed its yawning depths. (Their proximity no doubt encouraged by the fact that George had spent so much of his patrimony, not to mention time, furnishing the palace that he had no way to replenish it.) And so his daughter, Cornelia, opened it to the public in 1930. Perhaps it was intended to act upon the charred hopes of common folk as were the era’s movies, the spangled musical and the screwball comedy; not so much escapist as pure magic—a conjured world where there was time to dance, where love and humorously resolved minor troubles were the primary concerns. Whatever, the family had hit upon a way to maintain itself: as perverse spectacle. It offered the sight of the unimaginable to the invisible. Today the house remains in the family’s ownership, billed as “an American treasure.” But it is not now, and never was, any such thing. It is a treasure indeed—a million times a treasure—but it was never American; it was Vanderbiltian, a national economy unto itself, which fact is made manifest by the three miles of driveway that detaches this Valhalla of money from the world beyond.

It is the model to which we are now returned. Economically speaking, most of us still go to the outhouse while a few luxuriate in the hot water run directly into their porcelain tubs after they have discreetly flushed their waste down one of 43 commodes. We are at a moment with an odd sense of familiarity about it, a distant déjà vu. Did we get lost in the woods, wander for years, only to find we were traveling in a large circle and have returned to the point at which we set out? Because it looks like it: there have never been more people—46.5 million at current count—living in poverty in this country. Between 2009 and 2012, incomes of the top 1 percent of Americans increased more than 31 percent, at the same time the remaining 99 percent swept up the crumbs with just a 0.4 percent rise. (IRS statistics recently studied by a consortium of economists reveal that since 1993, the real incomes of the top minority of earners grew 86.1 percent against gains of only 6.6 percent for the bottom majority.) This means we fell asleep in 2012 but we woke up in 1912. That is when income disparity in this country was last this wide. If we are indeed in a hundred-year Groundhog Day loop, we still must look forward to tent cities springing up in public parks, more tone-deafness in a Congress that passes the equivalent of Smoot-Hawley Tariff Acts to further ream out what’s left of financial hope, and veterans hawking five-cent apples on street corners to hungry formerly employed businessmen who can’t afford even that. Today’s millions of “forgotten men” can only hope to stay awake long enough to see a candidate appear and offer a new deal. The old one stinks like rotten fish.

Meanwhile, the crowds press through Biltmore in a hypnotic dream, moving slowly so as not to step on the heels of the paying guest in front. They have spent $59 to view what would never be theirs—what is in fact representative of a political collusion by which what little they now have will be taken from them and given to the Vanderbilts by other names who build their own chateaux on the distant horizon. A sop is thrown to their longing, although they will have to pay for it, too: “Bring Biltmore® Home,” trumpets the brochure. And so you may wish to have your own Sargent portrait of George to hang in your hall, for $260. Or perhaps a five-piece place setting of Vanderbilt service china, for $85. It’s obviously no concern of theirs what will happen once you put it on your table. As luck would have it, it looks very likely it will not be holding much food.

“I never knew what it meant to fight to keep your head above a rising tide, because my father had coughed the water from his lungs in order that I would not have to. But he could not do this for all time. He could not keep me afloat my entire life. He was only so strong.”

This resonated with me so incredibly powerfully. Brilliant stuff-

“What great art went missing between the birthday party & the PSAT prep we’ll never know.” But this is exactly art.

Howdy! Do you know if they make any plugins

to protect against hackers? I’m kinda paranoid about losing everything I’ve worked hard on.

Any suggestions?

Utilize Ninjagram to remark on applicable hash tags in

your specialty just you don’t say some insane poop on pics and

make no since saying it. The Instagram likes you obtain really

should be authentic persons and can help in long run small business.

Driving your car an inundation most typically associated with Instagram likes to a specific part of

content is going to make the situation that rather more more than likely which your Instagram followers perform the given same, moving along the group more deeply and consequently much deeper within marital life on your Instagram bill ( space and giving an most unending amount healthy have an effect on.