Over the next month we’re excerpting Tessa Laird’s social history of the spectrum A Rainbow Reader. Last week in Part II we tackled war and peace, drugs and protest in the color Orange.

IT ALL STARTED with Yellow.

It was the late 90s, and we were driving back from an outdoor party. This one wasn’t held in the Mojave Desert, as was typical for the Southern California rave scene but in some rocky, pine-covered hills. Also different were the drugs we’d taken. Ecstasy, our drug of choice, wasn’t available, so we paid $5 each for liquid acid, administered from an eye-dropper and straight onto our tongues by the dealer, like communion. Not long afterwards, we found someone selling ecstasy, and in a rare moment of abandon my boyfriend suggested we do both. This is what’s known as ‘candy flipping’ – acid provides the visuals, but ecstasy keeps the trip from delving into dark psychic abysses.

The combination was incredibly intense, and, of course, I had to vomit. The music completely screwed with my spatial-temporal sense, and the pine trees were so staggering in their magnificence that any attempt to look up at them resulted in my falling on my ass. Remaining prone like a helpless insect was the safest position, and for much of the time all I could do was lie in a tent groaning as my (male) lover became a Vietnamese (female) prostitute, and I relived the whole sorry rape of Southeast Asia by the US military as a remorseful white Army private. Later two more friends tumbled into the tiny tent to make a human tamale. I thought I was going to die.

When the sun came out, we ventured forth from our tents. The only friend who had remained effortlessly clean-cut and hadn’t turned into a swamp-creature was nevertheless blowing bubbles, like the Thompsons in the Tintin adventure The Land of Black Gold (and subsequently Adventures on the Moon). I had pink hair at the time (I mean, it was really pink, a result of other sorts of chemicals, slathered on the scalp rather than ingested), and that magenta crowning glory along with my carrying a turquoise parasol while walking among pines gave everyone else visions of a psychedelic version of the Willow Pattern, Britain’s appropriation of mystic Cathay. For myself though, I was inside an Indian miniature with grey-green shrubbery and tiny yellow flowers; a wild-eyed Brazilian girl rolling in the grass became a gazelle with her kohl-rimmed eyes and long, coffee-colored limbs.

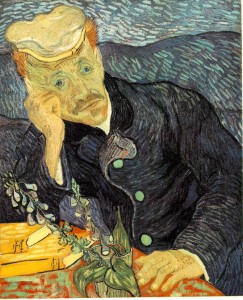

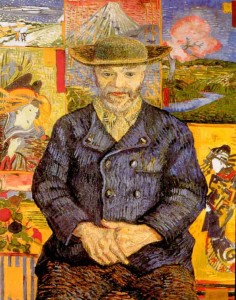

Eventually, it was time to go, and we piled into our friend’s white van. I was convinced we were speeding but apparently we were crawling. I was sick with fear. The only thing I could do to take my mind off imminent death was concentrate on the roadside flowers. I guess it was spring, or what passes for spring in the endless desert that surrounds LA. Everywhere, little yellow flowers had come out, and they made two yellow stripes on either side of the road like a canary-colored runway into the sun. Mesmerized by this royal carpet, I felt a surge of warmth and understanding for Van Gogh, so closely associated with this color, who once said, “There is a sun, a light that for want of a better word I can only call yellow, pale sulfur-yellow, pale golden yellow. How lovely yellow is!”[1]I wondered if the chemicals I had taken into my system had gone some way toward approximating Van Gogh’s supposed chemical imbalance. Alexander Theroux writes that “There are certain critics who ascribe the penchant for yellow of Van Gogh, an incipient xanthopsiac, as the possible result of his having been poisoned by digitalis, which at the time was given as a treatment for epilepsy.”[2] Certainly, in his last years Van Gogh painted a portrait of his Sanatorium’s Doctor Gachet with a “yellow book and a foxglove [digitalis] plant with purple flowers.”[3]

Vincent Van Gogh, Portrait of Dr. Gachet

Theroux continues on the unhinged artist and his crazy colors: “Vincent wrote to his brother Theo from Arles in 1890: ‘All the colors that the Impressionists have brought into fashion are unstable. So there is all the more reason to use them boldly… time will tone them down only too well.’”[4] And Phillip Ball picks up where Theroux leaves off, noting that the artist’s orders for materials “reveal a penchant for some of the most fugitive colors on the market, and clearly Van Gogh was neither ignorant of this nor too crazed to care. Rather, one almost has the impression that his primary concern was not for longevity but simply to get these garish visions out of his head. It was a head that, by all appearances, burned with sickly yellow, the ‘citron yellow’ of his café’s lamps, the sulfur yellow he perceived in Arles. In The Sower (1888) it is the yellow of the sun’s baleful glow, an orb that offers no warmth or comfort but looms like a sickly, incandescent moon.”[5]

And yet yellow was a color, according to Van Gogh, “capable of charming God.”[6] The artist, like the color he is most closely associated with, remains a paradox. Universally loved, he has become little more than a cliché in the art world, yet every original Van Gogh I have seen has gripped me in a way no other painter has managed. Walter Benjamin’s nebulous notion of the aura, the mana of the artwork’s presence which no reproduction could convey, was, according to Benjamin, actualized by Van Gogh’s late paintings. He wrote: “One could say that the aura appears to have been painted together with the various objects.”[7] Van Gogh’s paintings are palpable. They speak in the present tense about nature and life-force and energy and information, instigating the same toxic swoon as the magnificent swirling pines I saw at the all-night party, nature experienced in its raw state without the filters we create in order to sustain polite society, in order to not go completely insane.

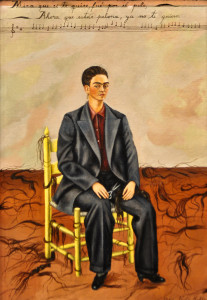

It wasn’t just Van Gogh I saw inside this carpet of yellow whizzing by my window; Frida Kahlo was there too with her Few Small Nips (1935), a scene in which a woman is brutally murdered by her jealous boyfriend. The yellow floor, covered with patches of blood, radiates a nauseating glow. In her Self Portrait with Cropped Hair (1940) Kahlo glares down the viewer from an oversized yellow chair, which, by the way, nods to Van Gogh’s famous yellow chair, the one he painted in 1888. Wearing a baggy man’s suit, Kahlo seems to have become the husband she lost to divorce in 1939. The identification with Van Gogh is deliberate – he severed his ear after rejection in love, and she has sacrificed her womanly tresses after one too many insults from the irredeemably promiscuous Diego Rivera. Kahlo’s diary revealed that yellow for her stood for “madness, sickness and fear,” but was also “part of the sun and of joy.”[8]

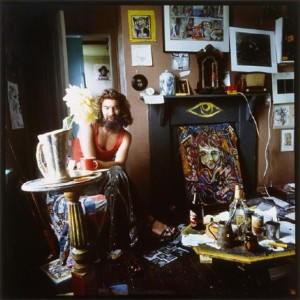

The New Zealand neo-expressionist Phil Clairmont, working in the 1970s in a drug-fuelled haze, and perhaps channeling Van Gogh, used a pungent yellow in his psychedelic interiors before taking his own life. He said, “It’s important to realize that when you’re actually painting, that painting is quite a down-to-earth business; you’re not emoting all over the place. I never shed tears when I apply cadmium yellow to the painting, although I love the color.”[9] Robert Smithson died in a light plane crash when he was surveying sites for his earth work Amarillo Ramp, which I guess you could translate as a “canary-colored runway,” except his trajectory was, like Icarus’, unforgivingly earthward. Then there was Kandinsky, who saw yellow as the cosmic firmament, the background against which his spiritualist shapes danced, and the Yellow Brick Road, the Yellow Submarine, not to mention just about all road signs (which are yellow) of altered consciousness. I remembered as we followed our own Yellow Brick Road in the white van from the party back to the Emerald City of Los Angeles that I’d always scribbled notes when reading, particularly passages with the color yellow in them, like about yellow kid gloves, yellowed paper and yellow journalism. Why was I so attracted to yellow?

The New Zealand neo-expressionist Phil Clairmont, working in the 1970s in a drug-fuelled haze, and perhaps channeling Van Gogh, used a pungent yellow in his psychedelic interiors before taking his own life. He said, “It’s important to realize that when you’re actually painting, that painting is quite a down-to-earth business; you’re not emoting all over the place. I never shed tears when I apply cadmium yellow to the painting, although I love the color.”[9] Robert Smithson died in a light plane crash when he was surveying sites for his earth work Amarillo Ramp, which I guess you could translate as a “canary-colored runway,” except his trajectory was, like Icarus’, unforgivingly earthward. Then there was Kandinsky, who saw yellow as the cosmic firmament, the background against which his spiritualist shapes danced, and the Yellow Brick Road, the Yellow Submarine, not to mention just about all road signs (which are yellow) of altered consciousness. I remembered as we followed our own Yellow Brick Road in the white van from the party back to the Emerald City of Los Angeles that I’d always scribbled notes when reading, particularly passages with the color yellow in them, like about yellow kid gloves, yellowed paper and yellow journalism. Why was I so attracted to yellow?

I bought a second-hand copy of Dear Theo, Van Gogh’s letters to his brother, in the hopes that I might get to the heart (or perhaps the yellow belly) of this mystery. But I didn’t get very far with the book, full of such quotidian detail. Perhaps, after all, my life in a San Fernando Valley group house where drugs and loud music were staples had little in common with Van Gogh, the earnest preacher’s son. Our vistas were different for one. He lived through harsh Dutch winters, and there was no winter in the scrubby desert where I was living. In the backyard was a pepper tree with bunches of pink peppercorns and a dusty prickly pear cacti. Pink lilies burst through the undergrowth, and turtledoves pecked around them in the leaf litter while the occasional grey squirrel scampered across rooftops. Ruby-throated hummingbirds, with their emerald wings, made frequent appearances. They are recycled warriors according to Aztec lore (and there were Aztecs, or their descendants, all around us, pumping out mariachi music even louder than our techno).

But I did copy this phrase from Dear Theo:

I always think that the best way to know God is to love many things. Love a friend, a wife, something, whatever you like, but one must love with a lofty and serious intimate sympathy, with strength, with intelligence, and one must always try to know deeper, better, and more. That leads to God; that leads to unwavering faith.[10]

I had just fallen in love, and I thought this was a good indication that I was on the right path. At that moment love and spirituality were one, and I felt like Parvati ravished by Shiva, or like a Sufi who sings about his beloved as a metaphor for the divine.

New Zealand painter Philip Clairmont perhaps channeling Van Gogh, photographed here by Marti Friedlander, 1978. Image courtesy of the photographer and the Christchurch Art Gallery.

~

The person responsible for bringing me together with my divine lover was G., and somehow, I associate G. with yellow, not because he was the golden boy of first the Auckland, then the Los Angeles art scene, but because we disagreed about that color as about many things. He claimed to hate yellow but made yellow art works and stole yellow flowers under yellow sodium street lights and ran a gallery with a yellow kitchen and bathroom. He took me to the yellow desert, where I met my yellow love, for which I should be eternally grateful. Yet, I could never feel anything but yellow bile between us, G. and me, and I swear I could smell the yellow smell of sulfur whenever he was near.

G. still maintains iconic status in various pockets of the art world years after his accidental death. He left Auckland for Los Angeles in 1996 to get an MFA. When G. lived in Auckland, he and a group of friends had set up Auckland’s first artist-run gallery. So in L.A., when his peers graduated and started to wonder what to do about their crushing debts, they hit upon starting up their own gallery and selling a shit load of artwork. In fact, they brainstormed the idea at a rave in the Mojave Desert. I’m sure it was G.’s hands-on experience that got the ball rolling, and he just happened to be at the epicenter of a new wave. The group rented a building in Chinatown, and soon, a raft of galleries opened on the same strip, Chung King Road, and it became a West Coast art phenomenon that everyone wanted in on.

While all this was brewing, I was wrapping up two years of directing The Physics Room gallery in Christchurch, New Zealand. I was itching to go overseas, and the first stop was Los Angeles, for the launch of G.’s new gallery. As soon as I got off the plane, I was plied with various drugs by a Kiwi ex-flame who had become a trucker in the States. This was to become a theme. Things were available here that you could only dream of in New Zealand.

Everyone, including G., knew the long-haired dude of Eastern extraction who always wore green (like any good native of Emerald City). G. invited him to DJ his gallery launch, and that’s when I first saw my future lover, in a dingy basement decorated with streamers, playing music I couldn’t understand, while the Kiwi trucker and his mate, another New Zealand import, waved their arms around in a drug-fuelled frenzy. I was terribly embarrassed. A few hours later I was in the juggernaut of the Big Rig, heading East across the country. But by the end of the month I was back in California, in the Mojave Desert, in the arms of the green guy. G. had gotten me there, on the condition that I paid for everything (the car rental and the drugs). He had insisted that he and I have three ecstasy hits divided by two, rather than one each. Perhaps this was why the lights ebbed and flowed with every pulse of the music (there are no lighting rigs in the desert, just the Milky Way and the moon). Whatever it was, my brain chemistry locked onto the coordinates of a specific individual, and they have been stuck in that pattern ever since.

It was a notorious party because someone died that night. A Latino teenager, taking acid for the first time, jumped around the massive rock formations and broke his back. On the way home G., our driver, fell asleep at the wheel, and we only awoke to the blaring of a horn as a car coming in the opposite direction swerved out of our way. Later that night, G. made me salads and encouraged me to take vitamins in a rare moment of caring. He was so full of paradoxes, with a cupboard full of supplements and a parallel desire to take every risk imaginable.

~

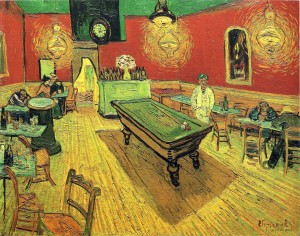

G. and I dated briefly when I was 18 and he had just turned 21. Our affair lasted all of two months and two weeks. I was still living at home, but my parents had a custom-built shed delivered to the garden the minute I became ‘sexually active.’ This became my bedroom, and I painted the walls lemon yellow with turquoise trim. G. ridiculed my choice, claiming that the yellow made him feel ill. Perhaps he was thinking of Van Gogh’s Night Café, of which the artist himself said: “I’ve tried to express the idea that the café is a place where one can ruin himself, go mad, commit crimes. I’ve tried by means of contrasts of delicate pink and wine and blood red, of Louis Quinze and Veronese green, contrasting with the yellow greens and hard white greens, all in an atmosphere of a devil’s furnace, of pale sulfur, to express, as it were, the power of darkness of a low dive.”[11]

Van Gogh’s Night Cafe, of which Vincent Van G himself said: “the café is a place where one can ruin himself, go mad, commit crimes.”

~

In 1890 Charlotte Perkins Gilman wrote a semi-autobiographical short story about post-partum psychosis called The Yellow Wallpaper. It’s a proto-feminist account of ‘hysteria’ being a by-product of marital and societal control of women. The story’s narrator has been confined to the bedroom of a country house by her physician husband for three months of rest. Instead, she becomes fixated on the room’s yellow patterned wallpaper, declaring, “The color is repellent, almost revolting: a smouldering unclean yellow, strangely faded by the slow-turning sunlight. It is a dull yet lurid orange in some places, a sickly sulphur tint in others.”[12]

And yet a few days later she writes: “I’m getting really fond of the room in spite of the wallpaper. Perhaps because of the wallpaper. It dwells in my mind so!”[13] Later still, she has nothing good to say about the paper that makes her think of all the yellow things she ever saw, “Not beautiful ones like buttercups, but old, foul, bad yellow things.”[14] A smell begins to bother her, which she can’t place; she ends up deciding it is the color of the paper itself: “A yellow smell.”[15]

The pattern that begins to emerge with alarming frequency from the paper, particularly at night, is that of a woman behind bars – like the narrator. Eventually the wallpaper woman liberates herself, slipping right out from her decorative confines, and lurking in the shrubbery of the old house’s estate. At this point, the wallpaper escapee and the narrator have completely fused identities – they have become one woman driven mad by confinement, forced to live in a two-dimensional world.

~

“Too much yellow light can cause arguments between people.”[16]

~

The yellowest artwork I can think of is by G. Called Golden Evenings, he made it in 1994, and I never made it to the show but saw an image of the work on the catalogue cover: an entire room painted buttery yellow with two peepholes at different heights in the walls. Two serious looking men in black eyeball the peepholes.[17]

When I first saw the cover, I felt sick (perhaps it was the yellow). How could G. ridicule me for painting my bedroom a delicate shade of lemon, then make an artwork of national significance which was a whole room in bilious buttercup? It’s an indication of my rather tangled emotions that I found this tantamount to plagiarism, or at least a clear case of hypocrisy. It never occurred to me that perhaps he’d painted the room yellow because he hated the color, because he wanted to induce repulsion in his viewers. Van Gogh wrote, “The picture of the ‘Night Cafe’ is one of the ugliest I have done. It is the equivalent, though different, of the ‘Potato Eaters.’ But (…) these are the only ones which appear to have any deep meaning.”[18]

Even Kandinsky, who used yellow so liberally and seemingly so lovingly, said, “Yellow is the typically earthly color. It can never have profound meaning. An intermixture of blue makes it a sickly color. It may be paralleled in human nature, with madness, not with melancholy or hypochondriacal mania, but rather with violent raving lunacy.”[19]

Kandinsky was the ultimate artist-synaesthete, who heard colors and saw musical notes, constructing a system of interrelationships based on what he felt to be universal truths rather than peculiarities. Sergei Eisenstein, on the other hand, was skeptical of this systematic approach, noting, “The gamut of color needed to create an image may be shot through with the yellow of sheaves of rye, the glinting curve of a scythe blade and the dazzling orb of the sun. In another it may be the man yellow of Chinaman’s face; a row of old-gold bracelets; or the yellow marks on the back of a salamander. Can this multiplicity of shades of yellow really correspond to a single musical note or to a single chord?”[20]

~

Journalist Victoria Finlay writes of the yellow pigment orpiment, that a woman in Batavia (Jakarta) in 1660 had become mad from it, “and climbed up the walls like a cat.”[21] Yellow and madness may have been the specialty of Van Gogh, but another artist illustrated insanity with cats. Louis Wain, the Victorian postcard painter whose charmingly anthropomorphized felines were his bread and butter, became utterly unhinged and started painting cosmic ur-cats, psychedelic phantom pusses in pulsating, radiating colors. Perhaps it’s because of the Psychology 101 textbook my father kept on his shelf, but to this day I associate Van Gogh and Wain, because they were both used as poster boys for mental disintegration as illustrated by artworks. Finlay goes on to talk about Victorian wallpaper poisoning, not as an excuse for the madness of these two artists, but as the possible cause of Napoleon’s death, among others. She also mentions a Persian cat that became covered with pustules after being locked in a green room.[22] I can’t help thinking of Wain’s demonic moggies against pullulating and possibly pestilent wallpaper, like those pulsating in the background of Van Gogh’s postman and the Woman Rocking A Cradle (both 1889), not to mention Charlotte Perkins Gilman and her inhabited yellow wallpaper.

The yellow and green theme at G.’s gallery was comparatively subdued, though perhaps obliquely referencing the Orientalism of bygone days. The gallery had been designed by well-known Los Angeles artist Pae White, giving the start-up space instant credibility. The kitchen was lemon yellow, very much like my old bedroom, only with a dark green, rather than turquoise, trim. But because this was the brainchild of an international art celebrity rather than an 18-year-old wannabe from Auckland, G. thought it fabulous (everything was better in L.A. than in N.Z., natch). Or maybe he had just mellowed (yellowed?), like old paper, or tobacco stains on a ceiling.

~

Michael Taussig writes about William Burroughs’ yellow bunker in the Bowery, downtown Manhattan, which was previously, perhaps appropriately, a YMCA locker room,

…whose mustard tones owed much to decades of young men’s sweating bodies. With a dash of sulfur, the sun that radiated out from Van Gogh’s sunflowers would revert to that other yellow, the yellow of hell and self-mutilation. The sacred likes to bite the hand that feeds it. It was scary, yet drew you in, not least because it was always just one step ahead of the game. ‘I kept myself going on coffee and alcohol,’ Van Gogh wrote his brother and benefactor, Theo, in 1889, the year in which he mutilated himself then took his life. ‘I admit all that, but all the same it is true that to attain the high yellow note that I attained last summer, I really had to be pretty well keyed up.’[23]

In the translation I have, the words used are not “keyed up” but “strung up.” And my own sick mind can’t help but think of Clairmont, and his chemical imbalance, which went well beyond coffee and alcohol, bringing speed and acid into the domestic interior, so that beds, chairs, couches and washing lines all leered with sinister intent on his shattered, kaleidoscopic canvases throughout the 1970s until, in 1984, he hung himself, strung himself up. Like a painting?

~

The artist John Christie, who published correspondence between himself and author John Berger on various colors in a book called I Send You This Cadmium Red, quotes a letter written by the painter Émile Bernard in 1890 describing Van Gogh’s funeral:

“On the walls of the room where his body reposed all his last canvases were nailed making a kind of halo around him… On the coffin, a simple white drapery and masses of flowers, the sunflowers that he so loved, yellow dahlias, yellow flowers everywhere. It was his favorite color, if you remember, symbol of the light he dreamed of finding in hearts as in artworks.”[24]

Christie is taken by a patch of sunlight that comes through the skylight of his home on a daily basis. It forms a warped rectangle of yellow, and eventually the painter is moved to paint it, to paint the wall yellow in the very spot where the sun shines; a kind of photogram-cum-mural. Suddenly, I understood a work by G. in which he as a young artist had painted a yellow oval on the ceiling of a gallery, and listed the primary ingredient as “spermicidal jelly,” a tongue-in-cheek critique of high-church Minimalists, for whom every decision, including what materials to use, where and when, verged on a sacrament.

~

One day I was sitting with G. in the gallery office while my East-West remix of a boyfriend was playing the turntables in the basement. G. started laughing because snatches of “Turning Japanese” by The Vapours started wafting up the stairwell. We chortled at this sophisticated, self-referential choice, sitting in the heart of L.A.’s Chinatown which, I wrote somewhere, was like Disneyland’s Toon Town only seen through slanted eyes.

It was when Van Gogh started turning Japanese that everything made sense. He wrote, “One’s sight changes; you see things with an eye more Japanese, you feel color differently. The Japanese draw quickly, very quickly, like a lightning flash, because their nerves are finer, their feeling simpler.”[25] Van Gogh had surrounded himself with Japanese prints: “My studio is not bad, especially as I have pinned a lot of little Japanese pictures on the wall, which amuse me very much: little women’s figures in gardens or on the beach, horsemen, flowers, knotty thorn branches.”[26] The “amusement” accelerates into a full-blown passion, an addiction, almost, as when he complains to Theo that “I find it dreadful sometimes not to be able to get hold of another lot of Japanese prints,”[27] and frets about his outstanding account with his dealer, a man called Bing in Paris, who, even in times of extreme financial stress, Van Gogh begs his brother to continue buying from.

Of Arles, he says, “Old chap, I feel as though I were in Japan.”[28] He writes that he will have to evacuate his yellow studio for the countryside if there is an outbreak of cholera in the summer. He writes, “I hope that later on other artists will rise up in this lovely country and do for it what the Japanese have done for theirs. I have no fear but that I shall always love this countryside. It is rather like Japanese art; once you love it, you never go back on it.” And then, in the very next sentence, conflating Japan, nature, and colors, all those ‘others’: “I am convinced that nature down here is what one needs to give one color. And the painter of the future will be such a colorist as has never yet been.”[29]

Van Gogh portrait of Pere Tanguy, 1887, in front of Van Gogh’s collection of Japanese prints.

~

He shot himself in a field of wheat in the noonday sun. He had written: “Yesterday I began a little thing that I see from my window – a field of yellow stubble that they are plowing. I have a canvas in my hand of a moonrise over the field, and am struggling with a canvas begun some days before my indisposition – a ‘Mower’. The study is all in yellow, terribly thickly painted, but the subject was fine and simple. For I see in this mower – a vague figure fighting like a devil in the midst of the heat to get to the end of his task – the image of death in the sense that humanity might be the corn he is reaping. So it is – if you like – the opposite to the sower I tried to do before. But there’s nothing sad in this death; it goes its way in broad daylight, with a sun flooding everything with a light of pure gold.”[30]

~

G. died, and it wasn’t a suicide and it wasn’t in a wheat field; it was an accidental overdose in New York, where he had been wheeling and dealing and partying with the same vivacious, charming greed he applied to everything. G., who loved medical imagery and once photographed a friend’s scabrous foot with a coroner’s tag, wound up in the City of New York morgue with a tag on his toe.

When G. died, his wake packed out MoCA’s Geffen Contemporary wing. Curator Connie Butler said that G. was in love with L.A., and L.A. was in love with G. I guess I learned from G. that unbridled ambition is a kind of love, maybe even the kind of lofty, serious love Van Gogh talked about, the kind that leads to God.

The photograph on G.’s memorial card was taken at a desert party. He is sitting on a rock, head thrown back in joyous laughter. It’s a grainy shot, and G. is dissolving, pixel by pixel, into the sun-baked sands of the desert. I try to imagine he died with a smile on his face, if not from the temporary high, then for the eternal notoriety of overdosing at the peak of his career. It would have been the same self-satisfied smile he wore the last night he fell asleep in my arms.

Next week, Tessa Laird’s spectrum study moves onto Green, not the color of jealousy, not money but love.

[1] Van Gogh, Vincent, Dear Theo: The Autobiography of Vincent Van Gogh, edited by Irving Stone (New York: Doubleday), 1946, 445.

[2] Theroux, Alexander, The Primary Colours: Three Essays (London: Paparmac), 1994, 148.

[3] Van Gogh, 563. In what is perhaps a more likely scenario, Xanthopsia is also associated with absinthe. Wallis, Robert J., “In Mighty Revelation: The Nine Herbs Charm, Mugwort Lore and Elf-Persons, An Animic Approach to Anglo-Saxon Magic.” Strange Attractor, Journal Four, London, 2011, 210.

[4] Theroux, The Primary Colours, 148.

[5] Ball, Philip. Bright Earth: The Invention of Colour (Hawthorn, Australia: Penguin), 2002, 220.

[6] Theroux, The Primary Colours, 141.

[7] Benjamin, Walter, On Hashish, translated by Howard Eiland and Others (Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press), 2006, 58.

[8] Hererra, Hayden. Frida: A Biography of Frida Kahlo. New York : Harper & Row, 1983, 284.

[9] Clairmont, Orlando (dir.), Clairmont on Clairmont, Artsville, Episode 13, TVNZ, 2007.

[10] Van Gogh, 44.

[11] In Artaud, Antonin, “Van Gogh: The Man Suicided by Society,” The Trembling Lamb (New York: Phoenix Bookshop), 1959, 13.

[12] Gilman, Charlotte Perkins. “The Yellow Wallpaper.” (1892). The Yellow Wallpaper, edited by Thomas Erskine and Connie Richards (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers UP), 1993, 32. Gilman wrote this in Pasadena, which was later the stomping ground of an unlikely trio, the occultist Aleister Crowley, rocket scientist Jack Parsons, and L. Ron Hubbard, founder of Scientology. It was also where G. went to art school, in mystery-shrouded hills where you might, if you were lucky, see David Lee Roth or a mountain lion.

[13] Ibid, 37.

[14] Ibid, 44.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Verner-Bonds, Lilian, Colour Healing: A Complete Guide To Restoring Balanced Health (Leicester: New Life Library; Anness Publishing Ltd), 1999, 40.

[17] Apparently what they saw was video footage of a sunset, a piss-take on the picturesque in New Zealand art.

[18] Van Gogh, 456.

[19] Kandinsky, Wassily, “Concerning the Spiritual in Art,” (1911), in Colour, edited by David Batchelor (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press), 2008, 61.

[20] Sergei Eisenstein “On Colour,” (1942), in ibid, 101-102.

[21] Finlay, 242. Perhaps this is the origin of “mad about saffron”?

[22] Ibid, 293.

[23] Taussig, What Colour is the Sacred? 34.

[24] Berger, John, and John Christie, I Send You This Cadmium Red (Barcelona: ACTAR), 2000, unpaginated, letter from John Christie dated August 97.

[25] Van Gogh, 422.

[26] Ibid, 370.

[27] Ibid, 418.

[28] Ibid, 396.

[29] Van Gogh, 409 (italics in the original).

[30] Ibid, 527.

”

The combination was incredibly intense, and, of course, I had to vomit”

I disagree, look at:

http://jcnewsandneighbor.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/851stedition.pdf Friendly, Laurine