IF WE MISS THIS,” I say, darkly, “I will be really, really cross.” And I will, but I won’t be that surprised, because isn’t the art exhibition that takes place a few hundred yards down the road from where you live the one that you’re most likely to let pass through, resolutely unvisited? But on this occasion I prevail, although – naturally – only on the day before the gallerists move in to take down the six tapestries that constitute Grayson Perry’s The Vanity of Small Differences.

A small number of Perry’s ceramic vases also feature in the exhibition; he is perhaps best known as the Turner-Prize-winning potter, and also for his tranvestitism, which finds expression in his appearances as Claire, a girlish figure swathed in nursery-rhyme frocks and ribbons. He is one of those Englishmen who seem to have got round his compatriots’ innate mistrust of artiness by trumping them with their fondness for an eccentric; and he has recently made a further bid for national treasure status (virtually an official title in this country) by focusing his gaze on one of our abiding obsessions: class.

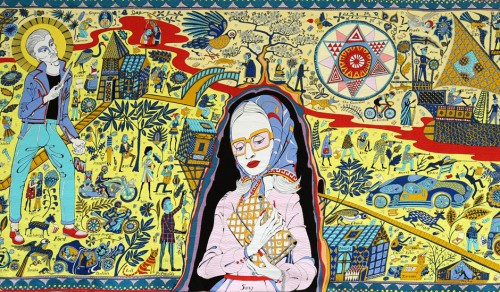

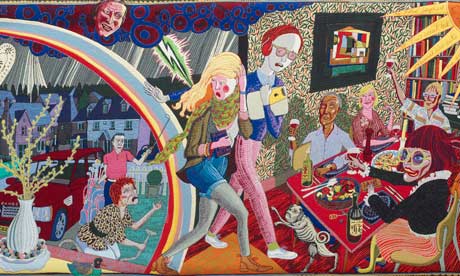

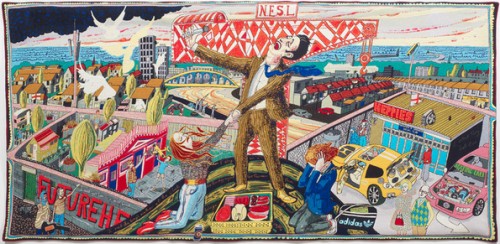

The Vanity of Small Differences is allied to a series of three television programs that Perry made called “All in the Best Possible Taste,” in which he parachuted himself into three different communities: working-class, in Sunderland, in the North-East of England; middle-class, in Tunbridge Wells, in Home-Counties Kent; and upper-class, in the Cotswolds (proper Middle England countryside). In each case, he attempted to build some kind of portrait of those he met by scrutinizing their tastes – how they choose to decorate their homes, what they wear, what they eat, what kind of language they use. And then, he wove a tapestry – a real one – and showed it right back to them.

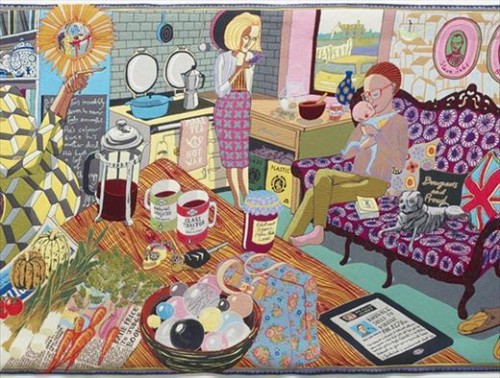

Grayson Perry and the signifiers of taste and class: Penguin Paperback mugs, Philip Larkin, iPads and a French press....

I confess it now; I am the ideal audience for this kind of stuff, and I love Perry. I particularly love his struggle with aspiration and with social mobility. I spent several years of my childhood in Essex, where Perry also grew up, and I now live about a five-minute walk from where he lives, in North London. I doubt either of us expected to find ourselves here, in an arty, affluent, leafy neighbourhood, surrounded by old buildings and old culture. The money round here’s not particularly old; for that you have to go further north, or further west, where the population is more aristo than journo and there are more hedge funders than psychotherapists. And there are pockets of Essex, to be sure, where there’s a lot, lot more money than there is here. But I don’t think those are the pockets that either Perry or I saw most of.

So it’s with a great sense of fellow feeling that I set off to see the tapestries, trotting past the MacDonalds’ drive-thru and the newbuild, recession-defying loft-style apartments outside which – and this almost makes us turn back, it’s so upsetting – there has been a hideous road traffic accident. The highway that leads down to the city is closed off; emergency vehicles and personnel swarm silently; in the middle of the road is a pile of protective leathers and boots that, we realise, have been cut off the rider of the motorbike that lies crumpled, too close to a huge lorry for comfort.

At which point it seems frivolous to go and see some artworks about soft furnishings and tableware and accents.

In fact, though, the tapestries are somber things, unsurprisingly since they are modelled on Hogarth’s scabrous cautionary tale, The Rake’s Progress. Here, Hogarth’s Tom morphs into Perry’s Tim, a prodigy who rises from impoverished beginnings to become an internet-age guru, embarking in the process on a class odyssey that takes him from rundown city centers and workingmen’s clubs to brightly lit interiors studded with patterned cushions and Mediterranean cookery to the crumbling estates of the landed gentry. And eventually, it takes him, in eerie echo of the scene we have just witnessed outside, to twisted metal and shattered glass on an inner-city carriageway.

It didn’t surprise me that the pieces that held my attention for longest featured tableaux that captured Tim at the moment where he was exiting one class but was not yet at home in another. I loved particularly glimpsing what I think was a copy of Philip Larkin’s Collected Poems lying on a sofa next to him; I imagine Larkin’s apprehension of the fear and hatred bound up in class tensions was a great comfort to him. I shuddered slightly when I saw the exact recycling containers that stand in the corner of my kitchen in Tim Rakewell’s irreproachably middle-class home; it reinforced my unexpressed anxiety that doing the right thing with my empty bottles makes me feel more socially secure than ecologically helpful.

What, I felt, as I walked home, was awe at Perry’s observational skills and at his ability to weave – literally – a story. I felt that he had done that brilliant thing: made a piece of work with as much heart as brains.

But I also felt a confusion. We know that traditional class structures – lower, middle, upper – are now thoroughly untrustworthy, in permanent flux, the barriers between them porous. We know that huge factors – economic instability, migrant populations, to name just a couple – have changed the face of British society forever. And Perry had gestured cleverly to much of this confusion. But what, really, do we mean when we talk about class? And what does it profit us to do so?

I wonder particularly what we are afraid of. One way of reading a modern-day Rake’s Progress – one way of reading Perry’s tale of Tim Rakewell, which ends in tragedy – is as a warning of the dangers of social mobility. And yet, in other contexts, we believe in it thoroughly: we want people to be able to be free to do as they wish with their lives, to be untrammelled by the constrictions – real or perceived – of their birth. And yet: if we are terrified of social mobility, where do we want people to go from, and to? And do we fear that, however hard they try – and as Larkin once suggested – they will never really escape their beginnings?

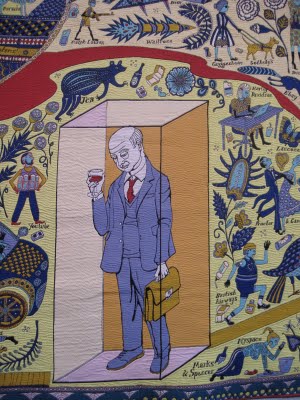

Another detail of the Walthamstow Tapestry, working man in a cube with wine. Of course probably bought at Marks & Spencer like his suit.

A week or so later, I pick up the weekend magazine supplement to see Grayson Perry on its cover, wearing a Panama hat, sipping a mug of tea, looking wide-eyed above the strapline: “What are you going to eat tonight?” It did not refer, exactly, to a recipe special – although fear not, there were plenty of those too, because it is virtually against the law to print a magazine without them these days – but rather to a hoary old chestnut: what people of different classes call the meals we eat at different times of the day. One thing is quite delightfully unproblematic here: we all seem to call breakfast “breakfast,” whether it’s eggs and bacon, or Cornflakes, or devilled kidneys, or coffee and cigarettes. After that, it’s a free-for-all: lunch isn’t exactly posh, but the working-classes will often refer to their middle-of-the-day meal as dinner, whereas those elsewhere on the class spectrum will use dinner to refer to a rather more elaborate meal eaten later on in the evening, some hours after the working-classes have had their tea. Confused? You will be, just as soon as we’ve started talking about supper.

Various celebrities had been canvassed about what they called what, with Grayson making some perfectly sensible and puckishly expressed points (“The word supper,” he suggested, “implies a subtle rebuke to the aspirational classes who are gauche enough to hold dinner parties at home”). But I found the piece as a whole unutterably depressing. Why? Because it is a piece that I could have read (and probably did) twenty years ago. This is not (really) a subtle rebuke to the magazine, because it was a nifty piece of commissioning and a fun idea. But its existence, however humorous, posited the idea of an actual problem that needed serious thought. And because no one they asked said – who cares about this shit anymore?

[Postscript: The postman, luckily enough, always rings twice. When we came back from the gallery, there was a note telling us that we’d missed a parcel and needed to go and collect it from the sorting office. But not long afterwards, there was a knock at the door. The postie had popped back again, just on the offchance we might have returned. Along with our package, he brought unexpected and cheering news: the motorcyclist had sustained two broken legs, but lived to tell the tale. This is, of course, unrelated to art except by peculiar coincidence, and quite probably has little to do with class warfare, but it is surely always worth passing on a happy ending.]