(Last week in Part I, Quentin Rowan met his match, his doppelganger, David Marks, both fourteen and at Friends Seminary.)

THIRTY YEARS EARLIER, and 2,756 miles away, a young boy in Hawthorne, California also named David Marks was just starting to play guitar with his friend Carl Wilson across the street. Carl’s older brother Brian was writing his own songs, and he liked the scratchy adolescent fury of Carl and David’s electric guitars in tandem. In April of 1962, Brian Wilson took David Marks along to a studio called Western Recorders to play on his songs “Surfin’ Safari” and “409,” which would become the first hit record for their new band, the Beach Boys.

The group was quickly snatched up and signed to Capitol Records where more hits were expected right away. David Marks found himself playing guitar and singing harmonies on tracks like “Surfer Girl,” “In My Room,” and “Be True To Your School.” They blasted from every channel on the transistor radio dial up and down the Sunshine State’s blue longitudes, soon the entire country. The songs seemed piped in from a charmed and forever-warming afternoon where history no longer mattered because children ran the world and the only stimuli they needed were sex, Honda scooters, and Collier custom surfboards. The future would be sweet as strawberry milkshakes on Venice Beach, that magic look from the amber-eyed bikini girl as she ran down to the white and infinite surf.

In a sadly revealing bit of misfortune, it turned out Brian Wilson had never liked the ocean. His brother Dennis was the surfer; Brian found the power of the ocean frightening. As a boy he’d suffered from night terrors. He began writing cheerful pop songs as a teenager to push away the voices and drown them out, but once the Beach Boys were famous, the voices were simply replaced by those of his father Murry and the executives at Capitol.

Because the Beach Boys had been pigeonholed by the surf craze, Wilson was brought back time and again to the subject of the Pacific Ocean. Like the narrator of “The Secret Sharer,” while “far from all human eyes, with only sky and sea for spectators and judges,” he was forced to contemplate the molten chaos, to sing the beauty of its pewter waves in two-minute radio symphonies until it drove him mad.

Similarly, it was the time David Marks spent with Brian Wilson – like the captain’s time with Leggatt – that allowed him to catch a glimpse of his own creative side, waiting dormant, desperate to be released. He quit the band at the height of their success, wanting to write his own songs.

Brian Wilson’s songwriting, like his ego, was delicate and worked best when he had David Marks and Carl to protect it with their heavy guitars. Marks’ own songs were darker, primitive in comparison, but powerful, like shadow to Wilson’s light. Having spent some time deepening his consciousness with the Beach Boys, David Marks, like some spirit embryo in second birth, formed his own band and signed with A&M. They were called the Marksmen and Murry Wilson reportedly asked local deejays not to play their records.

The Marksmen were big in California, but their records failed to sell nationally and they eventually gave up. Marks spent some time as a session player in Los Angeles before forming a new band, the Moon, with Matthew Moore (of the Matthew Moore Plus Four) and the rhythm section of proto-country rock outfit Hearts and Flowers.

The Moon lived at Continental Studios in Hollywood for months recording their baroque pop masterpiece Without Earth. Besides one ill-conceived song “Brother Lou’s Love Colony,” it’s a near-perfect record. Tracks like “Papers,” “Faces,” and “I Should Be Dreaming,” expand and exfoliate and reveal as much as any pop song could then, especially in the bloom-like days after Revolver, when a hint of the existential came whispering underneath luminous layers of George Martin-inspired strings and sitars. Unfortunately, the album was under-promoted and failed to sell. The Moon stayed at Continental and logged in 470 hours of studio time recording their second album, the more sophisticated and mysterious The Moon.

The sophomore effort has a hall of mirrors quality to it, almost audibly lysergic, which seems to turn some people off as much as it appeals to others who’ve been there, insomuch as it feels like a crystallization or rationalized version of the way one’s brain is occupied by LSD. Even without having tasted those otherwise unreachable frequencies, The Moon is still so agonizingly beautiful, faultless even. It’s astonishing that songs like “Lebanon,” “Not to Know,” and “Life is a Season,” with all their fragile, moth-like beauty weren’t major hits.

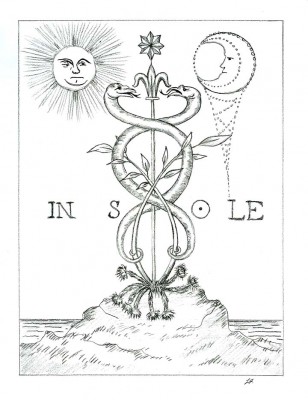

Interestingly, in the alchemical tradition, the moon is a feminine property, representing and sharing a strong association with water and tides. It reaches its greatest potential only when incorporated or joined with the sun. The famous alchemist Paracelsus wrote: “Just as the sun shines through a glass… the sun and the moon and all planets, as well as all the stars and the whole chaos, are in man.” But the moon gives off no light. It is a luminary body, but relies on light from the sun to project and mirror its image indirectly, through the black sleet of space, to our eyes on earth.

Water too, was important to the alchemist’s practice as a symbol of the unconscious. It was their belief that there was another, a higher person within our selves to give birth to. This could only occur through some expansion or deepening of consciousness. Just as the captain in “The Secret Sharer” reaches down into the night-blue sea to pull the rope that, like an umbilical cord, brings the naked Leggatt into the world, so did Brian Wilson, a living symbol of the bewitching power of sun and surf, take David Marks into his orbit until the latter had built up enough confidence to take control of his ship.

Twenty-one years after the release of The Moon, when I met my David Marks, something similar happened. I’d always thought myself whole, the captain of my own ship. But in the whirl of our brief time together that winter of 1990, I began to see the darker things, the thousands of sharp pieces toppling everywhere, trying to hold together inside me. It might be too much to say I was asleep in some silent place until David Marks woke me to some fuller experience of life as Leggatt does the captain, yet I can’t deny that I needed some of his light catching, even tearing, at me to begin my own journey.

I began writing poetry after he was expelled. We were reading the Romantic poets and the teacher asked us to do an imitation. Coleridge was too subtle for me and Wordsworth too long-winded, but I liked Shelley. The faces are obscured now, the memory, but I can still see the burst of interest, the congratulations, as I read mine to the class.

Several weeks later, I was with a delegation of teenagers, hunched under an aluminum archway when some early spring rain came bouncing down. A joint was lit and passed around, scarlet at the tip, with lush garlands of smoke floating off. A freckled girl blew dimples of smoke into my mouth. It scorched my throat but felt sinuous and ripply. Soon I was inhaling off the slender roach directly. By then it had stopped raining, but we were still standing under the rust of pipes and white street lamps and we began to giggle. It seemed the funniest thing on earth that we hadn’t noticed the rain stop through the flicker of smoke.

After a few months of smoking marijuana recreationally, buying weak twenty bags at a fake record store on Ninth Street, it occurred to me that drugs were possibly the connection missing between David Marks and myself the previous year. Maybe I’d seen him as an awkward bird because he’d been learning to fly in a completely different manner. I picked up the phone one day (he still called my house quite often) and agreed to meet.

It was June and blue rainfall had done wonders for the city. We met at some café in the West Village in full daylight, and he looked well, I thought, except for a jagged bowl-cut that was several inches shorter on the right side. I remember thinking I’d just sit there and let him do his thing and see if I could understand or not. If his words made any sense, then perhaps it would mean I’d misjudged him earlier.

The first thing he did was hand me a notebook, a five-subject college-ruled notebook filled with pencil chicken-scratch, and say, “That’s my novel.”

I reached for it, impersonating an interested party. “Oh yeah? What’s it about?”

“The Wheel of Time.”

“Huh.”

“You know it?”

“What?”

“The Kalachakra?”

“Hmm.”

“It’s like cycles, you know. Of the planets. of time. Even breath.”

“Right.”

I was catching some of what he said, minor bits of debris awash in the overall dispensing of wisdom. Sensing he could, possibly, dwell forever on the matter of the Wheel of Time and the illusory world of images that myself and the rest of humanity were still being fed by, I asked how his year at the United Nations School had gone.

“All right, I guess. But I got messed up on a girl.”

“Oh yeah?”

Suddenly he was an ordinary teenager again. Shuddering, embarrassed, far from the miasma of Eastern wisdom.

“Yeah, she dumped me pretty hard.”

“I’m sorry.”

“Right in front of all her friends.”

“Woah.”

There was something sinuous in his eyes as he spoke about her. The stain of hurt she’d left seemed real enough to cut through the sheets of menthol rising before him as if from the ruins of the Kalachakra itself.

“What are you doing this summer?” he asked after some time.

I suppose I’d been touched enough by the sadness as he talked about his girl that I felt unguarded enough to tell him my summer plans. I was going to Bennington to study poetry. David Marks nodded, his glance cast downward across the shadows chilling MacDougal Street, its collective of chess shops and head shops, untraveled that time of day.

I wish I could say I caught something, a word, a phrase, anything in his reaction to signify he’d caught interest and held onto the fact, but I didn’t. After a few moments of silence, I made an excuse and vanished down Bleecker Street.

So it was a surprise to see David Marks on my first day at Bennington, checking into the dorm across from mine. He still had his haircut and scuffed jeans and hunched shoulders, and to anyone else would have been just another nervy teen there to pass the summer in an educational fashion amongst the green shades.

For me, seeing him there, having told him I was going to Bennington and getting no response beyond the tiny upsweep of a nod, felt wrong, as though he’d made a deliberate point of stumbling out of nowhere, and securing a last-minute spot in the program, just to show me he could follow me anywhere. I might think it was my life, but he’d always be right behind me if I chose to look, a constant presence just inside the narrow frame.

I walked back through the afternoon to my dorm and found the guy with a touch of black hair spilling out from his ponytail, my RA, and told him the story.

“There’s this guy.”

“Yeah?”

“He just moved into Canfield.”

“You mean the guy with the weird hair?”

“Yeah.”

“Go on.”

“I think he followed me here.”

“How so?”

“I went to school with him, and we were sort of friends, but he started acting really weird and got kicked out. Then I saw him back in June and told him I was coming here, and he didn’t say anything, but now he’s here and…”

“I can go talk to Student Services and they can talk to him about it.”

“Really?”

“Sure. They can just sort of gently give him a warning, you know, not to bother you.”

That first afternoon of greetings and orientations, I met a guy named Stewart who liked the Velvet Underground and was handsome and graceful and confident, with a neat mantle of hair the color of dark chocolate. We sat together through orientation and then at dinner, after which we wandered out into the woods while the sky turned the color of grape gum.

Stewart had a soda can from dinner and we used it as a bong, which seemed to me to be the most inventive and resourceful thing a person could do in life. I remember the silver-flecked shine on the can under the soft flame, laughing, talking about the girls we’d seen so far, until my brain felt stuffed with marshmallows and we wandered back.

I made my way slowly up the ancient wooden stairs to my room only to find the door already open. There was a slight hint of ghost in the air, as the memory of locking it with the key in my pocket seeped back, and I peered in around the doorjamb cautiously. There was an old face, familiar, and saturated with something unpleasant, developing under the overhead light I’d just flicked on. David Marks.

He was sitting on my bed, back in the darkness. He’d broken in somehow and decided to wait in the dark. All I could make out were the main components. The bedroom deepness, the dark outside, the unexpected country coolness seeping in like a butterfly’s touch, those skinny legs crossed at such a familiar angle, the hunched back, posture worse than my own, just enough light to see his face, waiting, serious, ready for some sort of elevated discussion.

I could feel my brain inverting, taking in the frontiers of the peculiar scene, the fringes of unease turning into something more serious.

“What…”

“The door was unlocked.”

“I’m pretty sure I locked it.”

He rose, with no warning, light overhead catching his hair flowing asymmetrically, night-time silence around us springing towards a crescendo.

“Why did you lock it?”

“Cause I don’t want people to steal my stuff.”

“What stuff?”

“My typewriter.”

“Fuck your typewriter. Everyone’s got word processors anyway.”

“Fine.”

“So why’d you really lock it?”

“You’re insane.”

“Aha!”

“I locked it to keep you out.” I could feel my heart pounding as we stood eye to eye. Something in his face had exploded. He was all red, and time was flickering on and off. Slowing.

“What are you so scared of?”

“Look, man, I told you I was coming here. You didn’t say anything, and then you showed up. How can I not think you followed me?”

“What if I did?”

“Well, then it’s kind of fucked up.”

“Why? We’re friends.”

“We were friends. Then it turned out you were lying about everything and then you did that thing with Sarah… and… ”

We were still eye to eye. Who would look away first?

“And what?”

“And then you attacked Steve Kosinski and started throwing stuff at people.”

“So?”

“It’s not normal.”

The light in the room was growing very red.

“Look, man, you have to leave, okay?”

“Can’t we just talk?”

“No.”

After agonizing over it a few moments, he made for the door, but not before he flashed me a look that seemed to imply that I was the one in the throes of folly. Perhaps one day I’d understand.

“David.”

“What?”

“If you break into my room again, I’m going to have to tell my RA and he’ll tell Student Services.”

This appeared to be the worst duplicity, the final insult, and David Marks pulled back his head, hair shimmering in the light, and laughed while his face turned purple, hoarsely, in profile. He fled, blowing out the door and its broken lock, as if the whole episode had all been some game in the dark, at the edge of the mirror-frame, in a haunted room that sometimes breathed and sometimes sighed after night-fall.

Creeping into bed, I found the blankets rustled and remembered him sitting there waiting, long and slender, and the smell of his menthol cigarettes. I tried to sleep but couldn’t stop wondering what was it he wanted from me.

Meantime, my ponytailed RA, Jason, was true to his word, and when it turned out David Marks and I were meant to be in the same poetry workshop, had me transferred to a different one. I didn’t see David Marks for some time, as if Student Services really had spoken to him, and when I did, he’d slow down and stare. But shortly thereafter, he found a girlfriend, oddly reminiscent of Sarah, with dark hair bonneting her pale, severe face.

Coupled-up, he became a model of rectitude. Occasionally, I’d spy him across the dining hall shooting me sharp glances as he ate his cheese fries. Then he’d turn to his girlfriend and whisper something, and they’d erupt into bobbing laughter. I can only imagine what kinds of stories he told her, but my suspicion is that it it was simply this story with the roles reversed.

It was easy, though, to forget about it. I had new friends. Stewart and Stella and Lizzie. I had my poetry to work on and The Velvets cover band I’d formed with Stewart and Jason. Even further into the salt reaches of night, I had marijuana to smoke with Stewart, and now Stella and Lizzie, out in the grassy fur or the hills tucked below campus.

The summer had developed in such unexpected ways (girls, friends, writing) I forgot about the awful fear I’d experienced that first night. In fact, I began to worry once more, that I’d misjudged David Marks, that maybe it was me and not him. Two weeks before we were going to leave, all the poetry workshops gathered in an auditorium for a student reading. Everyone had to read something, one or two poems, with a five-minute time limit. David Marks was the second or third person to read. He rose from a magenta cloud of teenage boys all with similar brown hair and oily skin. At the podium he pulled out his manuscript and said, “Another Ten Thousand Years of Suffering.”

The large room, clustered as it was with kids pretentious as myself, had been shocked into something like silence by this remark. Was it the title of his poem, or some non sequitur?

David Marks went on to mumble for five minutes until he was forced to stop, reading what seemed to be a monologue from the perspective of Jesus on the Cross. The experience of sitting there listening felt somewhat analogous to be bludgeoned with the sharp edges of a copy of The Brothers Karamazov.

At dinner that evening I sat with some girls from my workshop who were discussing the death/ exile/suffering trifecta his poem seemed to be propagating, when one of them pointed out that whenever she saw him, David Marks was eating cheese fries, smoking cigarettes, or making out with his girlfriend. His life, it seemed, was tied to the immediate, to pleasure. In a sense, it was the reverse of his somber jeremiad about Time, Death, the institutions of Death, and really whatever else was worrying him. I burst out laughing because what she said crystallized something I’d sensed but never put into words.

But then, I too would go on to try to eat and smoke and steal my way to joy, to life. It would take years of bitterness, depression, and finally humiliation before I could see it didn’t come from outside. But really there’s no place where past and future meet, it’s all more or less fixed after the fact, and I still haven’t found a way to get back, past the dreadnoughts of time, to whisper in my own ear, let alone his.

That year autumn came in heedless of summer and destroyed it completely. I was depressed to be back in school again without any friends. The administration caught on pretty quickly, and my French teacher dispatched me to see the head of the upper school. Some poems I’d written for extra credit had the signalings of mania to them.

The upper-school man in his plaster room wasn’t so bad. He read me a poem about a panther by Rilke. The panther was cool, human-eyed one supposed, as it turned and turned again behind the frosted paint on the bars of its cage. And, of course, what it turned out he was trying to say was what everyone who’d ever worn a suit and gone to look at animals in cages before him had told me, “You build your own jails, kid.” There’s no such thing as depression, just like there’s no such thing as animals that can talk or magic children that move invisibly through the countries of night.

That November I visited Stewart in Washington and took LSD, which I liked because it made the clocks run faster, and the inward weave of my self-hatred not sting as much. When I reread “The Secret Sharer” now, the underwater world of Leggatt and the captain was simply a fog of shadow selves swimming the beaches of individuation, traversing the voiceless sea, night across night, waiting out each thousand-yeared whirl of the clock for the moment when one shadow could see itself in another and acknowledge that it contained everything it refused to accept about itself.