(In Part II, David Marks follows Quentin Rowan from the Beach Boys’ own David Marks to a poetry workshop in Bennington, Vermont)

THE WORD “WARLOCK” has had several definitions. Though it is generally assumed to mean a male witch, sorcerer, or wizard, there is some evidence that, back in the 13th century, the word (wǣrloga) simply referred to a traitor, deceiver, or a breaker of oaths. There is also a possibility it comes from varð-lokkur, an old Norse word referring to a “caller of spirits.”

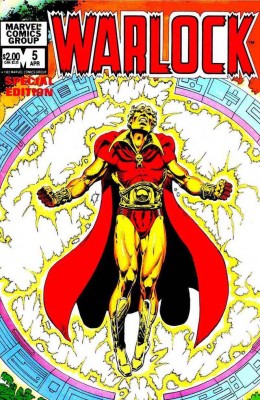

My own first encounter with the word was through a Marvel Comics character named Adam Warlock. He was a sort of super-being created in a lab called the Beehive to be the pinnacle of human evolution. Warlock was written in the Seventies by a guy named Jim Starlin with a trippy, cosmic vibe. Warlock has a Jesus Christ Superstar feel to him, wears something called the “Soul Gem” on his forehead and flies around outer space saving doomed races. Then one day he encounters his doppelgänger, the Magus. The Magus is an evil, purple-skinned version of Adam Warlock from an alternate universe, created through some kind of time paradox.

Warlock’s doppelgänger has been living on a planet called Sirus X where he’s gone insane, deciding he is a god, and starting up a little organization called the Universal Church of Truth. During a sort of intergalactic holy war, Adam Warlock goes up against his tyrannical second self and defeats him. In a moment that could only have been conceived of in 1975, Warlock returns to his own realm by following a “kismet trail” which resembles an actual path, through the galaxies.

Most doppelgänger stories, like Jim Starlin’s work on Warlock, tend to portray a protagonist at war with his double. Unlike Leggatt in “The Secret Sharer,” these doubles tend to be evil impersonators, hell-bent on ruining their other selves. Edgar Allan Poe’s “William Wilson” is a prime example. It features a slightly awful man named William Wilson who is followed wherever he goes by another man, also William Wilson whom he loathes and eventually sends to the graveyard, seeing only then that the second man was his conscience. Similarly, in Dostoyevsky’s The Double, Golyadkin brings on his own downfall, both socially and morally, with the inexorably building hatred he feels for a physical double whose personality is the polar opposite of his own.

Sometimes doppelgängers have to stand apart for a while to remember they once touched at the extremities, rested even, head-to-tail. The Grateful Dead and the Velvet Underground, for example, two bands we tend to think of as being diametrically opposed, were actually very much alike in their first few years. Both bands started out as the Warlocks, and as Mark Grief notes in the London Review of Books, both were founded in the same year and were “quickly taken up by other cultural movements and artists from other genres to furnish ‘house bands’ for collective projects.” In Northern California, in the communion of the early Acid Tests, the West Coast Warlocks had Ken Kesey for a guiding light, while back in New York, the East Coast Warlocks had Andy Warhol, who quickly installed them as the backbeat for his Exploding Plastic Inevitable, with its climaxing projections and lights and obligatory dancers.

But whereas Jerry and Phil and Pigpen were into a peace-time of acid-drenched summer evenings passing the pipe with Owlsley and Mountain Girl, Lou and Mo and John were tired folk. They lived in the city of night. They needed speed to bring them up, to that sharp, bitter cold world of factory-looped repetition, and heroin to bring them back down to the place with the white-painted organ and the overlapping compline choir of drag queens.

Both bands were generally considered to be better live than what they produced in the studio, and while the Dead went on to become partially known for their bootleg culture and migrant throng of worshipers, there are few live recordings of the Velvets droning on Sister Ray for an hour, or legendary unrecorded jams like “The Nothing Song” and “Melody Laughter.”

John Cale has said of the Velvets that the “aim of the band on the whole was to hypnotize audiences so that their subconscious would take over… It was an attempt to control the unconscious with the hypnotic.” This tells us something about why he and Lou chose to call themselves the Warlocks. The early Velvet Underground wanted to cast a spell over their fans. Perhaps the early Dead also saw themselves as Warlocks. Perhaps there really was a kind of enchantment to their improvisations, something transcendent from the brine of the unconscious sea, where sometimes a naked swimmer climbs aboard, a sharer in a world with no boundaries.

Every night a different show and a different rendition of “Dark Star” and with it another chance, another possibility of wiping out the frail ego, of crossing over, diving back through the shadows, the skimming wetness of the sea-embrace. But while both the Dead and the Velvets set out in 1965 to take us to the bottom layers of the collective unconscious, by 1967 they had become opposites of each other, with worlds of difference – geographical, cultural, musical, stylistic – separating them.

It’s interesting to note that the members of the Velvet Underground, like Golyadkin towards his double, tended to despise the Grateful Dead. In 1970, Lou Reed said of the Bay Area scene “… they’re getting third- hand blues. It’s a fad… People like the Jefferson Airplane, Grateful Dead, all those people are the most untalented bores that have ever lived.”

Maureen Tucker also talked about finding the Dead boring, and Sterling Morrison went so far as to say, “We left California alone for two years, because they’re so determined to do their own thing, their own San Francisco music. We were just rocking the boat – they don’t want to know about that.” Meanwhile the Dead, in their California world of light and color and uroboric space jams, like the double towards Golyadkin, seem to have been quite indifferent to the Velvets and their contempt.

It was only with the 1967 release of Lou Reed’s “I’ll Be Your Mirror,” a song about his experience receiving twenty-four rounds of electro-convulsive therapy as a teenager, that the sea of shared consciousness took on a different meaning. The treatment was administered to cure him of his homosexual feelings. What it did instead was make him blank and passive, unable to feel compassion for anyone else. The “I” of the song is no longer a dreamer in the collective dream, but simply a soulless reflection. His only role is to illuminate the apparent clarity and wholeness of others, like some sad little moon in a dimension of beguiling suns weaving a net of gold around the earth.

Perhaps net is the wrong word, perhaps it was something more like a cage. Imponderable. Visible only in moonlight. Seldom-encountered, but for the occasional wrinkle or flourish. By the age of seventeen I’d grown used to looking for those moments. Little illuminations. Specks of truth. When the gold fringes brimmed, seeped out into the blue for a bit. I was in the process of catching one, trying to, in the cafeteria at Oberlin College, when a tall icy girl named Catriona mentioned quite randomly that she’d gone to the United Nations school. I turned to ask if she’d known David Marks. She smiled deeply. She began to tell me stories that portrayed him as a kind of amusing maniac.

She recounted how he’d flow through the hallways on the verge of collapse, leaning against lockers or walls or even trash-bins, but it was always unclear why. Was he too tired to walk? Too high? Or was he simply so depressed, that skidding his shoulder along tiled school walls throughout Lower Manhattan was the best he could do?

This girl went on to tell me David Marks had developed a crush on a friend of hers. On Valentine’s Day, he got down sorrowfully on one knee before this lovely faun, with all her friends around her in the UN School cafeteria, light from the East River lacing their teenage forms, and recited a poem he’d written. Though it was very long, and his valentine rose before he was through, crying as she ran off though the late sun, the shadows of other boys, teachers, Cat remembered that the poem started out with the line, “I want to drink the juices of your vagina…”

Another year went by and I was a sophomore now at Oberlin. I’d just set up my first email account. I was in the computer lab when my high school girlfriend emailed from Reed College. I was surprised to hear from her; our break-up had not been pleasant, and the fault was mine. She wrote to tell me David Marks was there and she’d seen lot of him lately. When I asked what she meant exactly, she said: He’s been stalking me. Well, following me around, asking questions about you.

This was a new development. Was David Marks actually a parasite? Seeking out something similar in the cell-memory? Some sort of blight still looking for revenge? I apologized to her for the nuisance and told her how I’d dealt with it at Bennington.

When she wrote next, two years later, it was to tell me that David Marks was doing everything naked now. Going to class, going to dinner, going to bed. He did it all in the nude. She was frightened, she said. Everyone was. For a split-second I flashed on Leggatt swimming the Gulf of Siam, “ghastly, silvery, fishlike,” then typed in: Why?

As far as anyone was able to discern from him, it had started out with his streaking on an acid trip though campus. And, from there, something about the rejection of other people’s opinions, something about showing he no longer cared, something in the pure nihilism of the act had taken hold. He had hope now where once he had only known its absence, and if that meant alienating the student body of Reed College, apparently it was worth it insomuch as he was happy to no longer deny any part of himself. This was all of him, all that skin on display, down to the very last cell.

At a time in my own life when I was growing more and more concerned with covering my body and the things I saw as brittle about it, I found this sequence of events shocking. My earliest memories of David Marks, after all, were of him changing in the boy’s locker room. Was there something about that place and time that had stuck with him? Stirred up and started swimming through his molecules or memory on acid?

The image of his tearing out into the night like some visitation from a deeper place, wakening everyone he passed stayed with me. Sometimes I felt him to be running alongside me, naked and deathly-pale, but real as anything else in this world.

During a complicated period at Oberlin I fell in love with a girl named Eliza. She was tall and lithe with a lattice-like beauty that was hard to look at too long. Soon everyone else fell in love with her and I gave up. One gloomy afternoon at Mudd Library, she told me she’d transferred form Reed.

“Did you ever meet a guy named David Marks?” I asked.

She shook her head no.

“He… um. I think he ran around naked a lot?”

Her head bent, something shimmered inside her and she laughed with a little tremor.

“You mean Bare.”

“Bear?”

“Bare, you know, like naked.”

“Ha.”

“Yeah, everyone just called him Bare. I never knew what his real name was.”

“And he did everything naked?”

“Yeah, just about.”

“And people just let him do that?”

“I guess. I don’t know. He was kind of a fixture.”

“Huh.”

“Yeah, I almost signed up for this elective he was teaching. Students could teach electives for, like, half a credit.”

“Yeah?”

“It was a tour of the nude beaches of Oregon.”

“But you didn’t?”

“People warned me not to.”

“Because…”

“Because he was crazy.”