I.

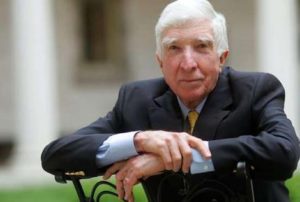

My relationship with John Updike was a complicated one in that it didn’t really exist. Or did it? With writers, it’s tough to say.

We can have connections, important ones, without ever meeting. They can be solitary admiration societies, one-way friendships of sorts. Or, they can be more conventional, involve shared human interaction, whether written, spoken, or (rarer still) the social graces required of real physical proximity. To be clear, though, John Updike and I were not friends, one-way or otherwise. But we did meet, once upon a time…

“John Updike fucking rocks,” I shouted at the darkened sky, doing my best impression of a nineteen-year old in the parking lot at a hair-metal concert. Honestly, that was the effect I was going for. And I’m positive I achieved it.

My friends Tom and Maria, and I had just gotten off the T at Government Center. It was cold and drizzly. The sky full dark, the lower air bright with lights from small storefronts and the blocky government buildings. There were people everywhere, some on their ways home, others headed out to eat or drink. We were on our way to Faneuil Hall for a reading, John Updike’s reading.

A little man in a fedora and trench coat scurried past, shifting his gaze for a quick appraisal of the caterwauling lunatic to his right. (That would have been me.) A glance and the little man was gone, a retreating shape against the night.

Some bean counter out to kill my fun, I probably thought. Which would have seemed a reasonable enough conclusion, I guess, for a bean counter like me, given a one-night-only furlough from his corporate prison on the sixtieth floor of the Hancock Tower.

“John Updike fucking rocks,” I said again, perhaps not as loud, still largely undaunted by my own stupidity. I was practically daring the little man to respond even as he faded into the distance. And he did, with the slightest nod, a sign of resignation, an acceptance that my lunacy would continue whether he wanted it to or not.

“Kurt, that was him,” Tom said, with a chuckle.

“What? Who?”

“Updike. That was him.”

“No.”

“Yes,” Maria agreed.

You may wonder how old was I then? Late twenties, something like that. I could probably figure it out if I had to. I was married (or close to it), living in Salem, home of fake witches and nightmare traffic. My future former wife, Sara, where was she that night? Somewhere, yes, definitely, obviously. But somewhere else, somewhere not with me. By that point, Sara had tired of literary events. She’d had enough of writers talking about writing as they went to see writers read their writing, as they sometimes got drunk and acted undignified in public. The whole scene was a real fucking drag for Sara, this writing hobby of mine. She had referred to it as that years before; something I was destined to never let her forget, something in the years since I’ve never let myself forget.

The marriage ended not so many years later. Two? Three? Five? I could figure it out, but would I sound horrible if I said it didn’t matter at this point? Even worse if I said I was glad she’s gone? Would I sound ridiculous, then, if I copped to still missing her once in a while? Or would that all simply sound human?

I’m not sure what I was thinking about at that moment, that night near Faneuil Hall, almost certainly not Sara. Maybe I was wondering whether that had really been John Updike, inventing scenarios in my head, one-way conversations as to what the great man had been thinking as he scurried away…

So this is what Rushdie was talking about? The fucking lunatics and their fatwas? This is what it’s all about, the fucking fatwas, and now they’ve come to America, to Boston? How I long for a simpler time, the years of my youth, the 30’s and 40’s and 50’s, before the world was broken, when all was still new and good, when liquor was cheap and we didn’t know smoking killed us.

I’ll need to call the police, of course, once I get to Faneuil Hall. And my agent to harangue her for not sending a car. The T? Riding the fucking subway at my age? God, and now I have to read. Okay, I can do that. But then the questions? And some asshole grad student (or two or six) trying to impress me, take me down a peg, or both? Or, what about this would-be executive over here? Maybe he’ll rush the stage. What if he’s armed? God, I hope they have security at Faneuil Hall. I really may need to call the cops. And after all that I’ll have to sign books. This is no way to spend a winter’s eve, not when you’re John Updike, icon of American literature, that’s for sure.

This wasn’t the real John Updike, though. This was a character, built of facts and rumors, biases and opinions. I still hadn’t met the real Updike yet. Rather, I’d glimpsed a little man scurrying away in the night, been told that was Updike, and created a backstory for him. I would meet the real Updike, though, a little later.

II.

I’ve only read one book by John Updike. Perhaps his most famous, the first in what eventually became the tetralogy of Harry “Rabbit” Angstrom, that book is Rabbit, Run, and I’ve actually read it twice, once for kicks, once for class. In my unscholarly opinion, Updike was a very talented stylist who wrote about topics I found (and find) uninteresting. Even the best attribute of Updike’s work, his prose, doesn’t always do it for me. At times, there’s no edge to Updike, almost as if he doesn’t care, as if writing is more a job than anything else.

Still, the man was incredibly successful as serious writers go. A major literary figure before I was born, he remained one until his death, and probably will long after mine. In this sense, there is some connection between us, tenuous and common as it may be. There were other connections, though, important if only for idiosyncratic reasons; connections that fleshed out the opinions I had of Updike, the constructed character I carried in my head as I approached Faneuil Hall.

There was the sage input I’d received from a grad school professor in the late nineties who told me to “Quit trying to write like Updike,” a goal (writing like Updike) that couldn’t have been further from my mind. In fairness to the instructor in question, he seemed fairly obsessed with the great man, not as an admirer of Updike’s work so much as his fame. The professor in question would pepper us with mentions of golfing with Updike, a veritable duffing bromance I expect amounted to one trip around the links many years before. This professor wrote page turners and screenplays, screenplays turned into page turners and page turners become screenplays. The entirety of his writing advice had to do with fame and monetary gain, the trappings of being a successful “author”, a word poisoned for me by its connection to this professor. In retrospect, he reminds me a bit of Donald Trump, if Donald Trump were a writing professor. This guy talked about stakes a lot, about always raising them in fiction. He made the same joke about grilling steaks again and again.

Then there were the days my wife and I spent with her friend up the coast in Ipswich, a place Updike had lived as a younger man. By that point he’d moved along the North Shore to Beverly Farms (and a mansion, I’m sure). And why not? All those books, many of them best sellers. The film options (The Witches of Eastwick, for example). After many years, Ipswich gossip still teemed with stories about John Updike, stories relayed by my wife’s friend, a life-long resident. She’d played with Updike’s children, looked on from a distance as he philandered around that small town, watched him eventually leave his young family and move, literally, down the street. So went the stories from my wife’s friend, so grew the legend of John Updike in my mind, a man who by circumstance and hearsay I became inclined to dislike, or at least to dismiss as boring and bourgeois, not worth my interest. Hence, my mock hysteria at the prospect of seeing him read. Sure, I was going. He was John Updike. But I was going with a chip on my shoulder, a little bit of insurance against disappointment.

The funny thing about Updike being bourgeois is that’s what I was becoming more and more myself, my career in finance advancing with those many halcyon midnights spent at that office in the Hancock Tower, my bank accounts getting fatter, writing time thinner, the act of writing itself growing more difficult until I stopped completely after I finished my MFA.

III.

There used to be a Waterstone’s by Faneuil Hall. The floors and floors of books and books, now all gone I think, turned into a food court or a fitness club, a Bloomie’s or a Macy’s. At that point, it was still a book store. That was where Updike went after the reading, to Waterstone’s to sign books.

The line for Updike was the longest I’d ever seen at a signing. It still is. The queue snaked from floor to floor of the store, through Science and Religion, Fiction and Children’s, doubling back on itself time and again. We’d been near the end of the line, but Tom and I had decided to stay, to wait. And eventually we’d gotten our chance, nearing the table where John Updike sat.

By the end of the evening, the Waterstone’s employees were imploring customers not to talk to Mr. Updike or make him sign too many books. The facts that should have been obvious: It was late at night, long after closing time. John Updike was nearing seventy. He was tired. People were imposing on him. And I watched as people continued to empty out their duffel bags and approach with their stacks of ten or fifteen books, watched as Updike signed them all without complaint, answered their questions about working at The New Yorker, whether he knew Cher and Jack Nicholson, the same questions he’d probably heard a dozen times just that night. Apparently, the Waterstone’s staffers were good at making blanket requests, bad at actually seeing them fulfilled. And Updike wasn’t going to do that. These were his fans. He was going to sit and sign.

We finally made it to the table, first Tom then me. I set the book I’d just purchased, In the Beauty of the Lilies, on the table before him. He took it in both hands, turned it and opened it, flipped to the title page. His pen descended, made its marks, as it had perhaps a thousand times that night, possibly millions in his life.

“Thank you, Mr. Updike, it’s an honor,” I said, star-struck, reclaiming my book, by that point feeling more than a little self-conscious about my bad manners earlier.

After all that waiting, after the liquor had worn off, I’d been forced to consider the reality of Updike rather than the abstraction of the character I had invented. He was an elderly man out on a cold night, sitting there, signing books. I hoped he wouldn’t recognize me. All I wanted was to get out of there.

“Well, I do fucking rock, don’t I?” he said, winking as Tom circled back, laughing, amazed.

And we stood there, the three of us, just three guys, three fellow dudes, as the rest of the world faded, as the last few people waiting in line disappeared, the store around us vanished, and all that was left were three writer dudes, laughing and laughing.

“I fucking rock, too,” said Tom.

“Well, you can goddam bet I rock, that’s for sure,” I added.

“Fucking rock,” said John Updike, “You guys fucking rock.”

IV.

Now that Updike is gone, dead nearly a decade, his fictional lilies wilted, swept away. Now that the rabbit has run and reduxed, been rich and at rest, we must reassess. We must deal with the reality of John Updike rather than the character constructed of myth and innuendo, the fiction that is fame, even such little fame as accrues to writers.

There are actually two things I remember about Updike’s work, two things that have stayed with me, and probably will until my death, I hope many years in the future. I think that’s all we can ask of most writers, as writers ourselves; or not ask really, but hope for, that some small bit of their work will stay with us in a meaningful way. For me, with Updike, the first is the beginning of Rabbit, Run.

“Boys are playing basketball around a telephone pole with a backboard bolted to it. Legs, shouts. The scrape and snap of Keds on loose alley pebbles seems to catapult their voices high into the moist March air blue above the wires.”

The rhythms, they’re what get me. “…Legs, shouts. The scrape and snap…” returns to me from time to time. No, it’s not the beginning of Lolita (though Updike clearly learned something from Nabokov). Still, it’s pretty good. It’s poetry, yes? Poetry become fiction.

The second thing that stays with me is the title of a later story of Updike’s, “Deaths of Distant Friends”. The lyrical beauty of that title—and more the truth of it—grows in my mind. The connections between people, the unavoidable loss of those connections, the sadness and joy that come with their memory.

I haven’t seen Tom and Maria in nearly a decade. It’s been even longer since Sara and I parted ways. As for John Updike, there was never a connection really, the end of the signing story an obvious fabrication. Admit it, though, you wanted that as much as I did.

Yes, I did meet Updike. And, yes, just as I said, I didn’t really know him. We weren’t friends. Except for the way certain people and events can fill our memories, can seem insignificant at first, then grow as the present retreats into the past.

I think of John Updike from time to time, of that night I met him, now years ago. More than Updike, I think of the people I’ve mentioned here and so many others, realities gone to the place all realities must, the shadow land of memory.

Beyond the veil, beyond our spent efforts and other, mortal failings, there can come visions, recognitions bright enough to change the way we see the world. These realizations are made still more magical by the fact that we had no cause for marking their consequence, nor that of the memories that spawned them, no obvious reason to do so when once we lived them, many years before.