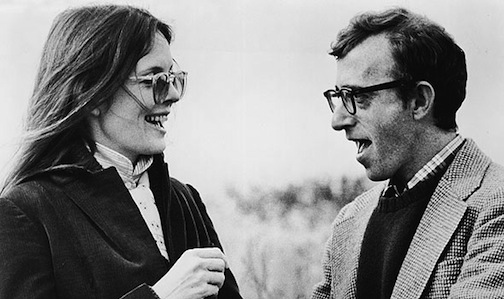

I CUT MY teeth on Woody Allen. It would almost be hard to overstate the symbolic significance, in my household, of being an Allen fan. I was eight years old when Annie Hall came out, and my parents immediately rushed me to the theater to see it. When I failed to properly enjoy the film (I’m so bored, I moaned over and over again, kicking at my seat), my poor parents despaired that I must not be very bright. Meanwhile, my father fell in love with Annie. It was 1977, and, like Annie, my parents weren’t “educated,” weren’t “worldly,” but they had…a certain style. My mother, full lipped, with a body reminiscent of Bettie Page and burlesque, had been a jazz singer in basement clubs in Chicago, though she could not read music and was never paid to perform. My father, a sharp-dressed bartender with a vague history of “nervous breakdowns,” didn’t drink, but kept a single bottle of gin on the back porch for when his failed-writer friends came over to talk about life and art. His hundreds of jazz albums were the soundtrack of my youth. Though they were radically out of place in our working-poor Italian/Latino neighborhood, in retrospect my parents actually fell into a cultural tradition of blue collar bohos. The infamous Rainbo Club where Nelson Algren had hung out was mere blocks away. And if economically, we fell below the poverty line, then Allen films, like jazz albums and Lenny Bruce, were a kind of secret handshake that conveyed…if not “sophistication” precisely, then the kind of style and smarts that couldn’t be taught—like what Annie Hall herself originally possessed. My mother and I often referred to my neurotic, self-conscious father as an “Italian Woody Allen.”

It is the first day of February, 2014, and my husband and I are driving to see the not-so-new-anymore Spike Jonze film, Her, in which a nerded-up Joaquin Phoenix falls in love with his more-human-than-human operating system, played by the voice of Scarlett Johansson. David tells me in the car on the way to the theater that he’s recently read an article claiming that if a couple wants to save money on marriage counseling, they need only go out and see five “relationship movies” and then talk about them afterwards, and the results are pretty much the same. This makes sense to me. It seems self-evident that the real problem in most marriages is a lack of communication and empathy. You see a movie, and you believe that the way you interpret the movie is the only way to interpret it: the character you relate to is the one with whom everyone’s sympathies will be allied. But of course that isn’t really true. Decades later, people still debate the assertion made in When Harry Met Sally that men and women “can’t be friends.” In the latest installment of the Richard Linklater films that follow the courtship-affair-marriage of Jesse and Celine, Before Midnight, most of my friends emerged from the film thinking Julie Delpy’s Celine was “difficult and crazy,” but my husband surprised me by being on her side, seeing her actions as a logical result of Jesse’s callous selfishness after their twins were born. Often, we sit side-by-side in a darkened theater with someone and we aren’t really seeing the same movie, even though we assume we are. Often, we lie side by side in a darkened bedroom with someone night after night, but we are not really living the same life…

My mother was sexually abused by her father. When she was three or four, he would take her to the park and feel her up behind bushes, his man hand inside her little-girl underwear. These incidents were finite, short-lived, but later, after her parents divorced, she feared being alone with him. Sometimes, he would take her on “dates,” leaving her baby sister, in whom he seemed less interested, behind, and when he took her home and said goodnight, he gave her deep “movie kisses” on the mouth. Like many abusers, he attempted to treat this like a game, like a secret, like a bond. Also like most abusers, he was not above violence and cruelty; my mother had vivid memories of being locked in closets by him when he still lived at home, and the reason her mother had left him to begin with was that he had taken up an interest in Christian Science and was refusing to let my mother get her tonsils out despite her persistent illness. It was the late 1930s, and in order to defy him, my grandmother needed a divorce, since it was not legally permissible, back then, to override one’s husband’s decisions. There were no legal caveats for that. Even when my parents married, in 1961, it was impossible for a married woman to own a credit card in her own name rather than her husband’s. While marriage was important to a woman’s social status, legal and economic freedom came only in being single. Once she had gotten rid of her husband, my grandmother was able to procure the surgery my mother needed. My grandmother—after whom I named one of my daughters—was no shrinking violet. Long before terms like “tiger mother” and “dragon mother” attempted to quantify the properties of maternal love, she used to carry her youngest daughter, suffering from nefritis, up and down a seven-story-walk-up on her back, just to get her some sunlight and fresh air during her months of debilitating illness; finally my aunt became one of the early recipients of then-experimental penicillin, which saved her life. My grandmother had divorced her husband to save one child, and literally carried another child on her back, but my mother still feared telling her about the bushes, the kisses, assuming she would be told she must be mistaken, that it was only a game.

After seeing Her, my husband and I go to the bar attached to the theater, which is a ritual of ours on movie nights. We talk about the movie, not because it is apparently an equivalent to marriage counseling, but because this is what we always do, have been doing since the first film we saw together in London in 1990. But what my husband wants to talk about is IBM Watson. He sees the Jonze film, accurately enough, as a kind of dystopian vision of what’s coming, of our current obsession with iPhones and the way teenagers now “watch a movie” by having the movie on the TV in the background while they tweet and snapchat and watch music videos on a smaller screen—the way “hanging out with friends” now often means sitting side by side on a sofa, emailing and texting people not in the room. Today’s youth seems to take in all information by scanning it. To someone my age, to whom beauty is in the nuances, this can feel like speed-reading through life. For a while, my husband and I debate IBM Watson vs. Scarlett Johansson’s “Samantha” in Her. My husband—a technophile with a PhD in space physics, who currently directs research at a trading firm, insists that such OS systems as Samantha are “going to happen,” and I know that the logical trajectory of the computer revolution since the 1980s would seem to not just support this claim but make it irrefutable. Still, the idea seems preposterous to me. Is there any evidence whatsoever, I keep asking, that computers can be taught sentient consciousness? That they can experience desire? That they exhibit will? David tells me stories about computers that can be taught—that don’t need to be programmed with their full set of knowledge, but can learn through experience, even physically, such as robots in a factory assembly line. This is strange, creepy even to someone like me, but it misses the mark of what I mean. The debate over whether computers can be made to be smarter than we are is already a dead one: clearly, they already have been. But where is the microchip of human desire? How can we program a machine to learn to feel? The discussion is apples and oranges. What I took away from Her is simply the way we are always evolving. That meaning isn’t static. That who we become doesn’t undermine who we have been.

David and I have an ongoing My Dinner with Andre joke. Like, you take a film and turn it into My Dinner with Andre. For example, Gravity is My Dinner with Andre in Space. Her, David quips, accurately enough, is My Dinner with Andre as an OS.

But really, Her is also a tech age Annie Hall. A classic Pygmalion story. As the world widens, we slip away from one another, from who we were. When I was a bored eight-year-old in the movie theater, my parents wanted me to be hip, smart, subversive: to get Woody Allen’s jokes. But a decade later, when I failed to carry on the blue collar boho tradition by actually going away to college, the first person on either side of my family to leave Chicago and go to school out of state, my father wept, saying hopefully to my mother, “Maybe she’ll fail out.” When I left to study abroad in England, he ended up in the ICU with a bleeding ulcer attack, hours before I boarded my plane. My parents had wanted a bigger canvas for me—had wanted me to have more than they had—but my widening canvas changed our insular triad of intimacy, together in the one-bedroom apartment of my youth. Like Annie—like Samantha—I grew wider, grew away. “I love you even more,” Samantha tries to tell her poor, jealous, human lover, who cannot understand her vast expansion, but is it really true? What might be true is, I see you more clearly. What might be true is that clarity is a kind of love. But more? I don’t know. What does love look like? Do our hearts expand infinitely, or do we have only a finite amount of love to give? Is a wider canvas a fertilizer for love, or a threat? The debates surrounding this may be at the core of human existence.

Only moments before going into the theater to see Her, I had learned of Dylan Farrow’s “Open Letter” in the New York Times. I saw the letter shared on the Facebook page of a close writer friend, Zoe Zolbrod, who has just finished a memoir dealing with her own childhood sexual abuse at the hands of a teenage cousin, and the way her silence and her family’s complicity led to another generation of abuse, until the perpetrator finally ended up in prison for molesting his own young daughters. I read the moment of Dylan crying out to Diane Keaton, saying “You knew me… Have you forgotten me,” with chills. I heard the voice of Scarlett Johansson, a favorite of Allen’s recent films, throughout Her, thinking of Dylan’s plea,“What if it were you?”

It seems self-evident that the real problem in society is a lack of communication and empathy.

And what does evil look like? Like love, it’s not a place on a map, not visible on a TSA body scan. The differences in collective vs. individual evil in particular fascinate me. The undeniable difference in the ensemble evil of the Nazi party, vs. the individual soldiers who comprised it, for example, most of whom were not sociopaths, were “normal” men, capable of love. As human beings, we are wise to fear the pack mentality. The mob brings out the ugliest side of people. But in that collective vein, are frat houses—bastions of hazings and date rapes—“evil?” Is Hollywood?

Experience leads me to the cynical belief that only rarely does anyone pay for abusing a child. I have listened to tearful revelations of molestation, only to years later see the named abuser gyrating on a dance floor with that same girl—now a middle-aged-woman—he used to terrorize. Often the story goes something like, She tried to tell, but nobody believed her, so she finally gave up and slunk back into the family fold, for fear of losing everyone. Sometimes, perhaps even more disconcertingly, the accusations are believed, and implicitly acknowledged among a small inner circle, but nobody ever names it again or drives the abuser out of that circle; everyone simply sinks into a mutual, exhausted complicity. My mother told my grandmother when my grandmother was elderly, my mother herself past middle-age, but her mother said she must have been misinterpreting or misremembering. It is important to stipulate that by then, my mother’s abuser was dead. That this was the woman who left him. They were no longer married when the abuse occurred. There was no risk to her, is what I’m trying to say. She was strong enough to leave him because of tonsils, because of closets, because he often woke the family up and piled them into the car in the middle of the night to drive them across state lines to some racetrack where he would bet and lose all their money. But she could not acknowledge what he had done in those bushes.

In her late twenties, before I was born, my mother received a phone call from a doctor. She hadn’t seen her father in years, but was informed that his diabetes, worsened by years of alcoholism, had caused him to get gangrene in his legs, and that he needed his legs amputated if his life was to be saved. My mother had to go in to sign the papers, as his next of kin. She went, signing on the dotted line to have her abuser’s legs cut off—a Girl With the Dragon Tattoo kind of moment of vengeance, almost: cinematic, rarely doled out in real life. But blood rarely quenches our thirst. The doctors told my mother that her father had been calling for her, begging to see her, ever since he had been brought in. They wanted to take her to him, but she refused, signing and then gathering herself up to leave. “They looked at me like I was heartless,” she told me, years later. “They thought I was a monster.”

“Have you forgotten me?” Dylan Farrow called out to Diane Keaton.

What does evil look like? Like anything else, of course.

I have a memory of being in a sleeping bag, alone, in the living room at a family friend’s house. The memory makes little sense: why wouldn’t I have been on the floor of their daughter’s bedroom, during this hypothetical sleepover? I was younger than the three kids who lived in the house; it seems bizarre to put a little girl alone in the living room, doesn’t it? Yet this is what the memory looks like in the movie of my mind, in my sensory recollection of the flat, dirtyish carpet underneath me. I woke to see the family’s dog standing in front of me, and for no apparent reason, the dog suddenly bit me on the lip and drew metallic tasting blood. Yet I have no memory of crying out, of saying anything to anyone, and in my memory it is as though I blinked and the dog disappeared. Maybe the whole thing was a dream.

Nearly two decades later, when I was studying to be a therapist, in the New Age, repressed-memory-saturated 1990s, I would briefly wonder, with a reductive A-to-A correspondence, whether maybe the dog was a man. But of course that’s crazy. Occam’s Razor would indicate that the dog was just a dog, or a nervous child away from home having a bad dream. Still, the memory occasionally still haunts me as what I’ve come to think of as a potential “Hawkeye memory.” You know, the M*A*S*H series finale, when Hawkeye remembers a Korean woman killing a noisy chicken to prevent their truckload of people from being discovered by the enemy and killed?

Except of course the chicken was a crying child.

Would you smother your crying child to keep a truckload of people safe? Bear with me for a moment, here. Most of us would say no, of course—we would choose our child over the other people in that truck, even if there were a dozen of them and our child’s life is merely one. But that dichotomy is a false one. If captured, the crying baby would be killed too, alongside everyone else. In the real equation, the child almost certainly ends up dead either way. Dylan Farrow’s life has been upended whether her father is a pedophile or her mother just a vindictive shrew. And amidst her wreckage, we, the public, the audience, are faced with the unpalatable choice of which grotesque scenario to believe, like some pop culture Sophie’s Choice. Except that Sophie’s Choice questions have no absolute answer, even though they consume philosophers and movie-goers alike. Should Sophie have chosen bullets for all three of them, right there in the line? Both children ended up dead anyway. Certainly questions like this keep me up at night, just like nights I’ve spent trying to work out some way the survivors of the Titanic could have permitted more people into their lifeboats. Could they have taken turns? But who would get back in the freezing water when their turn was up? Who wouldn’t just hit the stragglers with their oars and row away? What does evil look like? Often, exactly like fear.

Philip Seymour Hoffman died the day after Dylan Farrow’s open letter was published. Two of the professors where I teach were friendly with Hoffman—one a close friend of long ago, another more of a casual acquaintance—and both were hit hard, are mourning, have nothing but good to say about his character, warmth, humility. Both professors, I should add, are also in recovery. Hoffman had 26 years, and when someone goes out after that long, it frightens people who have clawed their way into an intact, sober life. I spent much of today with the ugly recurring thought that I would like to Sophie’s Choice Woody Allen for Philip Hoffman, which is just more false dichotomizing. I didn’t know Hoffman. Allen is widely loved by plenty of people too, and he, too, would be mourned in his death. Plus, in my A-to-A correspondence, Allen would have to load a needle and stick it into his veins, and he seems disinclined to do so. Who knows what Hoffman’s ghosts were? Though I have lived long enough to have come to the general conclusion that those driven hardest by demons of guilt and shame rarely have half as much to feel guilty about as those who put their own survival first and foremost, and are willing to smother anyone (She’s crazy! She’s a bad mother!) whose cries might get them caught.

For years my parents lay side by side in a darkened room, living different narratives of their marriage. My father had an unrivaled Madonna-whore complex, a self-consciousness at his own existence, and the combination was toxic to maintaining a sex life in a long term marriage. My mother, hungry for love and validation, could not stand to feel a man’s hands between her legs, and though she still desired a sex life, she was, by her own admission, repressed. Years stretched on, their shared life together two different films, interpreted two different ways—then later in a third way still, by me. By the time I was a small child, they had split the screen: my father now slept in the living room on the sofa; my mother, lonely, put twin beds into her marital bedroom and occupied one while I slept in the other. Over the years of my own developing need for autonomy, my family would play musical beds, until in the end, by the time I left the house, I slept in my parents’ old bedroom alone, while my father slept on the couch and my mother in what had once been a walk-in-closet under the stairs.

We hardly ever have sex, Woody Allen’s character in Annie Hall tells their therapist, only two or three times a week. We have sex constantly, is Annie’s story, god—two or three times a week.

I had a womanizing friend once (wow, usually stories that begin that way are a lot more fun than the one I’m about to tell…apologies…I have those kinds of stories too, but they aren’t where my mind is right now), who after many years dogging around was finally getting married. My friend had been physically abused as a child, though with a kind of deliberate sadism that creepily and sadly distinguished it from most stories of drunken fathers and belts and backhands. His mother ran their home more like a Rwandan child-army squad, with such mind-fucking acts as making him and his brother whip each other when one of them misbehaved, and egging on the one wielding the belt, yelling, “Hit him harder!” They were even forced accomplices in her torture of the family pets. Amidst all this, the two brothers sometimes played sexual games with their little sister. Games. That was how they thought of them at the time; they were all children. But years later, in adulthood, my friend had come to believe that what they had actually done was sexually abuse their little sister. Sometimes she didn’t want to play, but they coerced her. Maybe they used force, I don’t know. What I do know is that in his adult life, my friend called his sister several times trying to apologize, but she kept laughing it off and didn’t want to talk about it. He eventually had to cut it out, lest he upset her so much as to lose the relationship. One night, discussing the possibility of impending fatherhood, he said to me,“What if a man like me isn’t fit to have a daughter? What if I’m some predator, and I sexually abuse her?” I have been trying to figure out some way to explain with language why his words didn’t frighten or repel me. Why instead I looked him in the eyes and reassured him, “You would never ever do that.” I felt then—and I feel now—that I said the right thing, that I was right. I still feel like I’d take my instinct to the mat. But of course how would I know? Because we liked the same books, had a similar sense of humor? Because he helped me through hard times and was kind to me? Look at all the actresses over the years who have laughed with Woody Allen—whose careers he has nurtured. How can we ever know another’s core? Maybe my friend was crying out for help, and I failed to hear him. In another life, a less public life, would Allen have been able to cry out for help? Had he not been a cause-célèbre, might he have fessed up, been convicted, gotten treatment? Is any small part of him sorry, guilty, yearning to be accountable, but the collective force of Hollywood—the studio heads for whom he has made money; the actors he has paid—urged him on like frat brothers or the angry mob towards his worse self, turned him into the mask they want him to be? Are somehow even my unknowing parents, finding some elusive recognition and identity and pride in his films, complicit? How many of us could Dylan Farrow cry out to as she did Allen’s favorite actresses? Most sexual abuse of children involves some kind of circle complicity. The widespread sexual abuse of minors is a kind of cultural gang rape.

I know it is folly to think that it could still be possible that Allen would stand up and admit what he has done. I know that as long as his movies survive even his own lifespan—there will be those, even some feminists I respect, who insist that Mia Farrow somehow “brainwashed” her daughter into living a life of terrorization, so that she could “get back at” Allen—a scenario that, having three kids myself and having worked for years with sexual abuse survivors as a therapist, makes Farrow sound more powerful, brilliant and Machiavellian than most people happen to be, and also—incidentally—makes her a monster who cares nothing for her child. Such scenarios, for better or worse, seem less likely than that a man who has made repeated films about extreme May-December sexuality, and who married his long term girlfriend’s daughter, actually having abused his adopted daughter, considering the immense prevalence of sexual abuse in general. I know that it would be easy for Hollywood to simply leave the women Farrow in the water and row away to where the money and the glamour are, just as it is easier for me to remember my parents and my relationship with Allen films as a treasured childhood memory. But like Samantha in Her—like the computers my husband talks about who can learn—human beings have the ability to evolve, to assimilate new information, to be changed without that growth erasing who we once were. The frames in which my mother is led into the bushes by her father, in which my dad absurdly tries to convince the nine-year-old-ghetto-girl-me to dress like Diane Keaton, in which my friend who once feared he would be an abuser turns into a loving, protective father, all exist simultaneously. We loved Allen’s films because we didn’t know; we defended him at first because we are in awe of talent and seduced by fame and because his films spoke to our own fragile fears. Yet there is only so long, like some German townspeople, we can claim our ignorance now that the smoke is rising from the stacks. Above all, what if Allen himself acknowledged that this isn’t some movie open to multiple, equally-true interpretations: what if, instead of relying on the court of popular opinion and the cult of celebrity, he actually confessed? What would happen if he stepped outside the box of O.J. Simpson and aging abusers boogying on the dance floor? What if my mother had walked into that hospital room to hear her father say, I’m sorry. In the fantasy where I can swap an Allen for a Hoffman, the story ends there. In real life, in human life, there is always the possibility for evolution. What if the angry mob, instead of simple blood, demanded accountability, humanity?

What a beautiful essay, insightful and well-considered.

One problem I had with Her was how much empathy can a man have with an operating system. If love is reciprocal, what is the man giving to the OS? How is he adapting to ‘her’ needs and wants?

Again, a lovely piece. Congratulations.

This is absolutely beautiful. Probably going to keep me up all night thinking.

Bravely written, articulate, beautiful. Thanks for sharing this!

wow, nice to read something online that is well-written, for once.

“…human beings have the ability to evolve, to assimilate new information, to be changed without that growth erasing who we once were.”

That’s a beautiful standout line. I’ve had to pull away from being a longtime fan of Woody Allen’s work since this accusation resurfaced. Though I’ve loved films like Purple Rose of Cairo or Hannah and Her Sisters and though I’m living in France where Allen has long been treated as a kind of cultural demi-god, something has been lost for me. His films since the early nineties have either been cardboard imitations of once creative filmmaking or have featured an older character, as portrayed by Allen himself, screwing younger ditsy women or involve what I see as Allen confessing his own guilt, à la Match Point where we watch a man literally get away with murder. Either way, it’s too hard to stomach anymore. I don’t know if that’s qualifies as evolving, but reading this essay that weaves together these recent events of public discourse, I’m willing to give myself at least the benefit of the doubt.

As usual, a pleasure to come across your writing.