IN 19TH CENTURY France, a position in the Paris Opéra Ballet was the dream of many a poverty-stricken girl. The ballet offered a chance to escape the gutter, to find fame and fortune if she had talent and ambition, and in many cases, if she was able to attract the attentions of a wealthy male admirer. Along with their own private boxes at the Paris Opéra, men who held season tickets—the abonnés—had purchased entrance to the foyer de la danse, a space built to encourage encounters with the ballet girls. Charles Garnier, the architect of the opera house, intended the lavish foyer as the perfect showcase for “the charming swarms of ballerinas, in their picturesque and coquettish costumes.” Wives and male dancers were not allowed to enter, and it was there that the abonnés went to mingle with the lightly-clad ballet girls as they warmed up pre-performance and during intermissions. Here highlife met lowlife; the foyer served as a sort of gentleman’s club where industrialists and noblemen with enough clout to advance a girl’s career sought mistresses. In his memoirs, Louis Véron, a 19th century director of the Opéra, writes, “Attending the Opéra was fashionable; keeping a ballet girl even more so.”

~

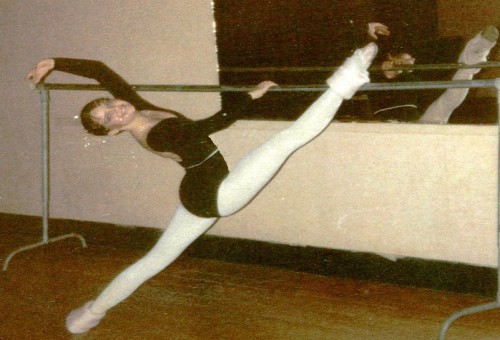

As a teenager in Niagara Falls I spent four, sometimes five, nights a week in the basement of an old bank on the American side of the river, a large low-ceilinged room that had once—a yellowed sign told us—served as a bomb shelter. The ballet mistress, who’d trained with the National Ballet of Canada, would call out, “A little more sweat, if you please,” and at the barre, we would plié more deeply or arch our backs more fully. Sometimes we would have a moment’s rest, and I would roll stiffness from my shoulders, gazing at one of the Edgar Degas prints tacked to the walls. I felt a kinship with his ballet girls, sometimes glorious on the stage but often as not scratching their backs or limbering at the barre just like I was. I saw their heaving ribs, their exhaustion, their thighs trained to roll outward from the hip. I saw their love of dance, too—no different from my own—and their commitment to perhaps the most grueling art form in the world. Decades would pass before I discovered the seedy roots of the Paris Opéra Ballet and the exploitation of the ballet girls I had once so admired.

~

In the corps de ballet of the belle époque, the girls were paid less than subsistence level wages and counted on patronage to put ballet slippers on their feet and meat on their tables (the ideal ballet girl of the day was of a “decent voluptuousness”). It was commonplace for abonnés to lobby the Opéra’s administration for a girl’s advancement through the ranks of the ballet and to pay the claque to lead the theatregoers in the orchestra stalls into a frenzy of applause on a girl’s debut. Once she achieved première danseuse status, she left behind the crowded, shared dressing room of the corps de ballet and was awarded an ornate boudoir-like individual dressing room—one more befitting the abonnés she would receive there once the curtain fell. The cost of patronage could escalate far beyond slippers. Abonnés gave gifts of jewels and fine lace, paid hairdressing bills, and swallowed the cost of private lessons and even carriages and luxurious apartments, generally in return for sexual favors. The Opéra turned a blind eye, even facilitated the sexual trafficking. They may have called it patronage, but through the lens of our modern age, it appears as little more than preying upon the young and poor.

Marie van Goethem, the model for Edgar Degas’s famous sculpture Little Dancer Aged Fourteen, was a typical ballet girl of the era. She lived on the lower slopes of Montmartre, a few blocks from Degas’s studio. Her father, a tailor, was dead, and her mother was a laundress. She would have borne the raw, reddened hands and the stooped, aching back of one who scrubbed, beat and wrung laundry from dawn to dusk six days a week and a half day on Sunday in return for the few francs that kept destitution at bay. Marie trained at the Paris Opéra dance school and was later promoted to the corps de ballet. It is not known whether she had drawn the attentions of an abonné and reaped the security such a liaison would provide. But when Degas unveiled Little Dancer in 1881, the public—all too familiar with ways of the Opéra—assumed that she had. They called her a “flower of the gutter” and said her face was “imprinted with the detestable promise of every vice.” Underpinned by a long history of sexual liaisons at Opéra, they saw a fourteen-year-old girl as depraved—a whore.

Edgar Degas, Little Dancer Aged Fourteen, 1878-1881, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon, courtesy of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC.

Much as was the case for Little Dancer, any blame for the questionable liaisons fell squarely on the shoulders of the ballet girls. Never mind that they were perennially underpaid and often as not stalked by poverty. Never mind that the alternative to the ballet was the laundry, the same drudgery and hardship Marie’s mother endured. For accepting the security the abonnés offered, the girls were deemed to have the “lightest of morals” and called sauteuses, a word meaning both “those who leap” and “sluts.”

In his memoir, Véron asserts that the girls—lowly pedigrees or not—knew “all the tricks of coquettishness” and were well schooled in “the art of being beautiful.” The historical record seems to suggest that despite advantages of wealth and education, the Opéra’s finest gentlemen had been hoodwinked by the scheming, clawing, sluttish ballet girls. Those exploitative men get off scot-free. “Protector” was the term most commonly used to describe the relationship of an abonné to a ballet girl he both fondled and fed.

As I delved into hard truths of their lives researching my novel, it became apparent that any kinship I felt with Degas’s ballet girls was sorely misplaced. Society had advanced, and in our modern age, ballet was by and large a high-minded pursuit of privileged young girls. Long gone were the days when men attended performances to ogle ballet girls as a sort of foreplay to the possibilities of afterwards. Only it soon became clear those days are not long gone and are hardly over.

~

Anastasia Volochkova, former soloist with the Bolshoi Ballet, has in recent months accused the Bolshoi Theater’s general director, Anatoly Iksanov, of turning the famed ballet company into a “giant brothel” where dancers as young as thirteen were expected to have sex with sponsors. She first made the claim on a Russian TV talk show and then repeated the assertion to the Russian media. “It mainly happened with the corps de ballet but also,” she said, “with the soloists.”

“Ten years ago,” she said, “when I was dancing at the theater, I repeatedly received such propositions to share the beds of oligarchs. The girls were forced to go along to grand dinners and given advance warning that afterwards they would be expected to go to bed and have sex. When the girls asked: ‘What happens if we refuse?’ they were told that they would not go on tour or even perform at the Bolshoi Theater.”

Iksanov has been quick to dismiss the accusations as “dirt and ravings,” and some say Volochkova, who was famously dismissed from the ballet for being “too fat,” has an axe to grind. But I am left uneasy. The Bolshoi, for years now, has been mired in scandal. A few weeks ago the veteran principle dancer Nikolai Tsiskaridze, who has repeatedly accused Iksanov of corruption and advocated for his removal from the company’s leadership, was fired from the ballet. In January a masked man threw sulphuric acid into the face of the artistic director, Sergei Filin, and dancer Pavel Dmitrichenko has been arrested on charges of arranging the attack. Two years ago Gennady Yanin, who was under consideration for promotion from company manager to artistic director, was ousted from the Bolshoi after graphic images of him having sex with other men were circulated across gay-intolerant Russia. And now, with Volochkova strangely snapped to silent, one cannot help but wonder if she has been threatened or bribed, not when so much is clearly unwell at the Bolshoi Ballet.

In belle époque Paris, the abonnés had the power to make or break a girl’s career, and in many cases, to spare her a life of utter destitution. The high-mindedness of the art and the status of the abonnés muddled the view of what amounted to the sexual trafficking of young girls at the Paris Opéra Ballet. Is it possible that the same factors have contributed to another of the world’s foremost ballet companies—one mired in scandal and accusations of corruption— serving as a “giant brothel,” this time in our modern age?

There are easy parallels to make. Same as for the 19th century Paris Opéra Ballet, today’s Bolshoi is recognized worldwide as dance powerhouse and national jewel, and is integral to the social life of the country’s elite. Like the 19th century Paris Opera’s corps de ballet, the Bolshoi’s gives the impression of an endless stream of girls—90-odd females compared to fourteen for London’s Royal Ballet. I do not claim expertise in the values of contemporary Russia, whether they might be aligned with those of the belle époque society that permitted, even encouraged, young girls to sate the longings of high-ranking gentlemen. I have noted, though, that President Valdimir Putin recently divorced his wife, seemingly for a rhythmic gymnast half his age. There is the old adage about smoke and fire, too, and certainly smoke billows from behind the curtain of the Bolshoi Theatre. But more than that, the combination of young ambitious females and powerful men with the authority to make or break their careers has proven itself time and again to be profoundly flawed. This is an age-old power dynamic, and to see it’s still in operation is truly depressing.

Though I never quite cut it as a real ballet girl, I think about my innocence as I stood at the barre, seeking the perfection that sets a girl on the stage. And I wonder now if I should be grateful that my footwork sometimes lagged the music, that my insteps are not the high sort necessary for the exquisite lines sought by the art of ballet.

Reading an article about ballet and how not too long ago ballet was a way out of the slums for the girls whose mothers could scrape up enough money to enable them to take classes. So they could attract a mate of means. This article mentions that there some of the balcony and box seats could be used for private assignations.

It reminded me that even in Tombstone Arizona, in the wild west where it couldn’t get any cruder or ruder there was The Bird Cage Saloon. The saloon didn’t have a high balcony but it had a mezzanine where there were “box seats,” with doors on them.

It would appear that all the classes had their way of getting their way in private. Or at least pretend private. The Hoi Poloi want the lower classes to think that they, the upper classes, are all that dignified and resigned. And they were just human like everybody else. All the classes were equally guilty of snogging where and when ever they could.

Pingback: 5. Belles of the Belle Epoque | The Land of Desire

In my case i have worker who would have people believe that about people with addh and pain of body eg. Arthritis both hips back and knee scoliosis dyslexic

I don’t know what they want. I think they want to ho me out. This case worker epic Sherry sends behind me dangerous drug people. People I would never talk too.

Pingback: Why the ballerinas of the Paris Opera were considered easy-going girls – Eigoinfo