THIS MORNING WHILE making us migas—the tex-mex version with strips of corn tortilla in the scrambled eggs—my boyfriend told me a story about translation. When he was in his twenties and working at a bookstore in London he was visited by his friend Tim, a former college roommate. Tim was working for the UN in Budapest then, translating a document for a brief for the World Court. Before his visit to London, Tim asked a woman he was dating in Budapest if she wanted anything from his trip. She asked for a Gabriel García Márquez book, the one that appears in English as 100 Years of Solitude. Not knowing what the title was in English however, the woman had translated it herself, and Tim showed up at the bookstore with a slip of paper that offered the title The Lifelong Loneliness.

Having read 100 Years of Solitude some years ago, my memory of the book squares well with this title, with its historical scale and sense of exuberant tragedy. The Lifelong Loneliness sounds a more intimate book, more ordinary, but perhaps because of this, a sadder one too. I’d like to read this book and find myself wishing the woman in Budapest had translated more than just the title.

It’s perhaps a commonplace of how we think about translation in the present to acknowledge that it is a subjective rather than objective art, and that a translator is not a neutral conduit through which a text can cross languages without gathering new content from the changed context and leaving behind untranslatable remains. But it’s important in telling this story, in this case the story about translation as a practice, to acknowledge not only the affect of the translator as a intermediary and of language as her medium, but also the text’s geographic and temporal journeys—ones in which the translator enacts a series of border crossings that are political as well as semantic.

This brings me to the story that in this text has prompted these others, Dante’s Inferno. An epic poem seven centuries old, the Inferno is one of the most translated texts of all time. This undoubtedly has to do with its relevance to so many times not its own, but I wonder too if it has something to do with the relationship of the narrative itself to translation. In the Inferno Dante famously plays himself, guided through Hell by the poet Virgil. Through Virgil Dante situates himself in relationship to the past and so assumes his influence to the future through this lineage. But it’s not just Dante’s insertion of himself into a canon that seems to demand his text’s proliferation throughout time, but more importantly the centrality of border crossing to the narrative of the poem itself. To cross from living to dead and back again is about as transgressive a passage as can be imagined; after this, where can’t the text go?

Mary Jo Bang’s new translation of Inferno and Patricia Cronin’s paintings inspired by the poem are two examples of the Inferno’s transgressive potential realized in the collapse of borders not only spiritual, but geopolitical and temporal as well. Bang’s Inferno translates the 14th century Italian to 21st century English while including references to music, literature, political figures, and popular culture of the present, just as Dante himself did for his contemporaries, while additionally providing notes that offer an invaluable history of the text and its many translations. Also like Dante, Bang is first a poet, and her translation privileges the rhythm and flow of her text over a pedantic interpretation.

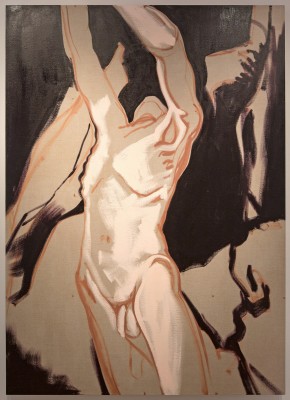

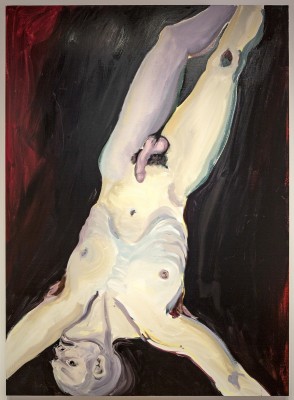

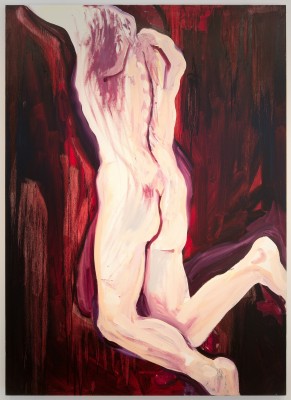

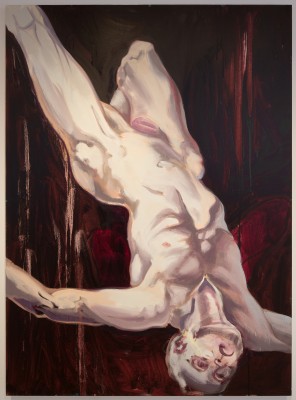

Cronin’s previous projects, while working across different disciplines and mediums, have always been about the political body—specifically the political body as seen from a queer, feminist perspective. They have also emerged from a love of the histories of painting, sculpture, and literature. When one inhabits a desire that isn’t represented in these histories, however, to love them becomes synonymous with the desire to rework them, to expand traditional methods and narratives to make room for the objects of ones own desire, and in the case of the Inferno, one’s own demons. For example, Cronin described an earlier group of watercolors of her and her partner making love as, in part, a rethinking of Courbet’s The Origin of the World—a painting of a naked woman in bed in which the point of view is between her legs, looking up her body. Only in Cronin’s paintings, this time it’s a female gaze on a female body. Her work inspired by the Inferno has a similar sense of intimacy, as if somehow she was there with Dante and his shades. This is another sense in which her work, like Bang’s, brings perspectives to the places and people of the Inferno that would have been unimaginable to Dante. Such is the work of good translation.

~

The following excerpt of Bang’s Inferno, which include Cantos XXXIII and XXXIV and their notes, were chosen by Cronin to accompany her work. Inferno by Dante Alighieri, translated by Mary Jo Bang, appears with permission of the author and Graywolf Press.

~

CANTO XXXIII

THE sinner lifted his mouth

From his gruesome meal, wiped it

On the hair of the head he’d ravaged,

Then began: “You’d have me refresh my sense

Of desperate grief when just the thought of it

Rips my heart in two—even before I utter a word.

But if what I tell you will plant the seed

That will flower into notoriety for the traitor

I’m gnawing on, I’ll talk through my tears.

I don’t know who you are, or how it is

You’ve come down here, but hearing you speak

I assume you’re Florentine.

If so, it’s enough for you to know I was Count Ugolino;

And this one, Archbishop Ruggieri.

Now I’ll tell you why we’re such close neighbors. 15

I don’t need to tell how he devised an evil scheme

To have me, who’d trusted him,

Seized and then put to death,

But what you couldn’t have heard

Is how cruel my death was. Now you’ll know,

And you’ll decide whether or not it was justified.

There’s a narrow slit of a window in the loft—

That after what happened to me is now known

As Hunger Tower (it’ll still have more men in it)—

Through which I’d watched the moon come and go

Several times when I had a bad dream

That tore a hole in the canvas that covers the future.

A man with a miter, dressed as master of the hunt,

Was chasing a wolf and his cubs

Toward the mountain that hides Lucca 30

From the houses of Pisa. In front of him,

Were long-legged scenthounds, eager and lean,

Plus men from three Pisan families.

After only a short time, the father wolf and his sons

Seemed exhausted and I thought I saw wounds

Where the hounds’ teeth had torn through their hindquarters.

I woke just before dawn to the sound of my sons,

Who were with me, talking in their sleep

And whimpering for a bite of bread.

You’re a cruel man if it doesn’t sadden you

To imagine my dread at what I saw was coming.

If this doesn’t bring you to tears, what would?

Now they were awake and it was nearing the time

They usually brought us our breakfast;

Each of us had had a nervous-making dream. 45

Then from below I heard the sound of someone

Hammering nails in the door to the terrible tower.

I looked at my sons without saying a word.

I didn’t cry; you’d think I had a heart of stone,

But they were crying and my youngest, sweet little Anselm,

Asked, ‘Why are you looking like that? What’s wrong?’

Still, not a tear, and I said nothing

That entire day and that night,

Until the next day’s sun lit up the world.

As soon as a few rays of light found their way

Into the prison gloom and I could see

From their four faces what mine must look like,

I began to chew my hands in grief.

Thinking this was evidence of hunger,

They immediately stood up and offered, 60

‘Father, it would be less painful

If you’d eat one of us; you dressed us

In this worthless flesh—now take it.’

I calmed myself so I wouldn’t add to their suffering.

All that day and the next we didn’t speak—

Cruel earth, why didn’t you crack open?

On the fourth day, Gaddo threw himself down

On the floor in front of me, pleading,

‘Father, why won’t you help me?’

That’s where he died. And just as you see me here

In front of you, I watched the other three die

One by one, on days five and six. I was already blind

But I crawled from one to the other, feeling for them.

I kept calling to them for two more days, even though

They were dead. Finally, starvation overcame grief.” 75

When he’d finished, he sneered at the awful skull,

Then grabbed it and bit down hard,

Locking on to it like a dog on a bone.

Ah, Pisa, you shame the rest of us

Who live in that lovely land where one says sì for “yes.”

Since your neighbors are reluctant to punish you,

I hope the islands of Capraia and Gorgona

Drift over and stop up the mouth of the Arno

And drown every last one of you.

Even if Count Ugolino had, as they say, betrayed you

By trading castles for favors, you shouldn’t have

Put his children through that torture.

Their young age, you neo-Thebes,

Made Uguccione and Brigata,

As well as the other two, entirely guiltless. 90

We kept walking and farther on came to other shades—

Their heads were crudely cocooned in ice;

Their faces, instead of bent down, were turned up.

Their very tears prevent them from crying.

The evidence of their grief is stopped at the edge

Of their eyes and backs up to increase their misery.

The initial tears freeze and form a glass ledge

That catches the next set and on and on until finally

The entire eye socket is filled with ice.

Although any feeling had already left my face,

The cold having caused it

To go numb like a callus,

I now thought I felt a wind blowing. I asked,

“What’s causing the air to move—there can’t be wind here,

Right, since there’s no source of heat?” 105

My teacher said, “You’ll soon be

Where your own eyes will tell you

What’s bringing down this blast of air.”

At that, one of the sad bad ones in the ice-crust

Cried out, “You ghosts, so cruel

That you’ve been assigned this final station,

Could you remove the ice-mask from my eyes

So I can release a little of the grief

That fills my heart before my tears refreeze?”

I told him, “If you want me to help you,

Tell me who you are—then let me be sent

To the lowest level if I don’t relieve your misery.”

“Fine,” he said, “I’m Fra Alberigo, the one who ordered

Fruit from the evil orchard; here I am, paying—

With interest—an empire of dates for the few figs I served.” 120

“Oh,” I said, “then you’re already dead?”

“I have no idea how my body’s doing

Up there in the world,” he explained.

“You see, this region of Ptolomea has a special feature:

A soul headed here often tumbles down

Even before Atropos cuts the thread.

To make you all the more willing

To scrape this plate-glass panel of tears from my face,

I’ll tell you more: the instant a soul betrays

The way I did, the body is taken over by a devil,

And it becomes a Boilerplate, a mechanical man,

Until its clock runs out

And the soul pitches headfirst into this pit;

It’s possible the body of the soul who’s wintering here

Behind me might still be walking around on the earth. 135

You must know if you’ve just arrived.

He’s Branca d’Oria. It’s been years

Since he crawled into this deep freeze.”

“I think,” I said to him, “you’re putting me on.

Because Branca d’Oria is definitely not dead.

He eats, He drinks, he sleeps, he picks out clothes, he puts them on.”

“In the ditch of the Psycho-Clawz,” he said,

“Above here, where the thick sticky tar boils nonstop,

Michel Zanche hadn’t even arrived

When a devil moved in

And took over that man’s body; the same thing

Happened to his treacherous partner-in-crime cousin.

But now, reach out your hand and remove the ice

So I can open my eyes.” Reader, I refused.

The only courtesy due a traitor is contempt. 150

You people of Genoa, you’re a race estranged

From everything ethical and you’re pie-eyed with vice;

Why haven’t you been banished from the planet?

Here, with one of the worst spirits of Romagna,

I found one of yours who, for all his evil mischief,

Already has his soul submerged in Cocytus,

While his body moves above as one of the living dead.

~

CANTO XXXIV

“THE banners of the King of Hell come forth,”

My teacher said, “and straight at us.

Look ahead and see if you can see him.”

Like when a thick fog lifts, or like at dusk

In the Western world when one can just make out the hint

Of a wind turbine turning in the distance,

I thought I saw some mechanistic device like that; then

Due to the wind, I ducked behind my teacher,

Since there was no other shelter.

I was now—and I’m filled with dread as I write these lines—

Where the shades were completely covered,

Visible through the ice like bits of straw trapped in glass.

Some are lying flat; some are standing head-up;

Others are upside down; some are bent over,

Their faces facing their feet. 15

When we were close enough,

My teacher wanted to point out the creature

Who’d once been a pretty little love-god;

He stepped to one side and made me stop, saying,

“Look, it’s Dis, and this is the place

Where you have to arm yourself with courage.”

Exactly how faint and frozen I’d begun to feel,

Don’t ask, Reader, because I can’t express it;

Words could never capture it.

I didn’t die. But neither did I go on living.

Think about it, let your mind focus a little

On what I’d become: not dead, but no longer alive.

The Emperor of Kingdom Woe was stuck

In the ice at the level of his chest;

I’m closer to being the size of a giant 30

Than giants are to the size of his arms.

Imagine, now, how large the whole must be

In proportion to a part like that.

If he used to be as handsome as he is now hideous,

And raised his eyebrows in contempt of his creator,

One can see how every bit of ire, envy, and despair

Derives from him. I was totally astonished

To see his head had three faces:

The one in front, facing us, was red;

There were two others, joined to the first

By a seam that began at the center of the shoulder;

The three became one at the crown.

The face on the right was pasty yellow-white;

The face on the left looked like that of those

Who live where the Nile begins in Africa. 45

The two enormous wings that emerged from under each

Were of a size that makes sense for a bird that big;

I’ve never seen a sail that large at sea.

They were featherless and webbed,

Like bat wings. He flapped them nonstop

To create three waves of downdraft,

Which is why Cocytus is forever frozen.

He cried from all six eyes

While tears and bloody drool dripped from all three chins.

In each mouth he chomped on a sinner,

Using his teeth like a flax-mallet

To keep the three in perpetual pain.

For the one in front, the biting was nothing

Compared to the clawing: at times

His back was a mass of missing skin. 60

“That soul up there suffers the worst,”

My teacher said. “Judas Iscariot.

His head stays inside, while his kicking feet stick out.

Those other two whose heads hang down,

The one dangling from the dark mug is Brutus—

Look how he thrashes without uttering a word—

The other is Cassius, who looks much more muscular

Without his skin. But night’s coming again

And we have to go. We’ve seen all there is to see.”

As he wished, I put my arms around his neck.

He waited until the wings were open wide, and then,

Like girls gathering roses, seized the time and place

To grab onto the shag on the side and lower himself,

Bristle by bristle, through the thin space

Between the matted pelt and ragged ice rim. 75

When we came to where the femur pivots

And the hip is thickest, my guide, straining

And short of breath,

Turned himself around so his head was where

His feet had been, and clutched the hair and pulled

Himself up, as if we were heading back to Hell.

“Hold tight,” my teacher said, panting like a man

At the point of exhaustion. “These are the stairs

We have to take to escape from so much evil.”

He exited through a crevice in the rock

And sat me down on the edge to rest,

Then he carefully made his way to where I was.

I looked up, expecting to see Lucifer

Just as I’d left him but instead

His legs were leading up. 90

If I was perplexed by this, let simple minds

That fail to grasp what point I’d passed

Consider how they would feel.

“On your feet,” said my teacher.

“We still have a long way to go; it’s not an easy road

And the sun says it’s seven-thirty a.m. again.”

Here we were, not in a palace stateroom

But in an oubliette formed by natural forces,

Dim-lit, with an uneven floor.

“Teacher, before I tear myself from this Hellhole,”

I said, once I’d stood up,

“Talk to me a little while and clear up my confusion.

Where’s the ice? And him, how is it he’s fixed like this,

Upside down? And how, in an hour and a half,

Did the sun move from evening to morning?” 105

He told me: “You imagine you’re still on the other side

Of the center, where I grabbed onto the hair

Of that wicked worm that burrows through the world.

And you were there as long as I descended,

But when I turned myself around

You passed the point of maximum gravity.

You’re now under the southern celestial hemisphere,

Opposite the one that canopies the continent

And where, at the highest center, is the site

Where the man who was born sinless and lived

Without sinning was put to death. Your feet are on

The small circle that forms the other surface of Judecca.

It’s morning here when it’s evening there,

And the one whose hair we used as a ladder

Is fixed right where he was before. 120

He landed on this side when he fell from Heaven

And the landmass that had been here

Recoiled in horror. The sea closed like a curtain.

That land then migrated to earth’s other side;

Whatever he displaced was forced up to form the ground

We’ll find above, perhaps creating this cavity.”

Down there, in a remote corner—

The distance of Beelzebub’s tomb times two—

Is an area one can’t find by sight in that low light

But only by the sound of a stream that,

As it trickles down a slight incline,

Has carved a winding canyon through the rock.

My teacher and I entered that secluded passage

That would lead us back to the lit world.

Not wanting to waste time resting, we climbed— 135

Him first, then me—until we came to a round opening

Through which I saw some of the beautiful things

That come with Heaven. And we walked out

To once again catch sight of the stars.

NOTES TO CANTO XXXIII

13–14. Count Ugolino; / And this one, Archbishop Ruggieri: Ugolino della Gherardesca (d. 1289) was a Pisan nobleman from a Ghibelline family. To extend his powers, he conspired with his brother-in-law, the Guelph leader Giovanni Visconti, to seize Pisa. He was subsequently banished but later allowed to return. He then conspired with Archbishop Ruggieri degli Ubaldini, a Ghibelline, to discredit his nephew (Giovanni’s son) Nino Visconti, an innocent Guelph.

17–18. To have me, who’d trusted him, / Seized and then put to death: After Nino Visconti was exiled, Ruggieri turned on Ugolino and accused him of having given away some outlying castles to the Florentines. Ruggieri had Ugolino, his two adult sons, and two teenage grandsons imprisoned; he then starved them to death.

25–26. I’d watched the moon come and go / Several times: The men were imprisoned in late July and they died in early February.

28–31. A man with a miter, dressed as master of the hunt . . . Pisa: Mount San Giuliano divides Pisa and Lucca. In Ugolino’s prophetic dream, it appears that Archbishop Ruggieri (the master) is chasing Ugolino (the wolf) and his family toward Lucca, an area where the count had political connections.

33. Plus men from three Pisan families: Dante names three prominent Ghibelline families from Pisa who sided with Ruggieri against Ugolino: Gualandi, Sismondi, and Lanfranchi.

50. my youngest, sweet little Anselm: Dante calls the boy Anselmuccio; -uccio is a diminutive suffix used as a term of endearment. The grandson was approximately fifteen years old.

67. Gaddo: The fourth son of Count Ugolino.

82–84. I hope the islands of Capraia and Gorgona . . . stop up the mouth of the Arno / And drown every last one of you: Capraia and Gorgona are two small Mediterranean islands close to the mouth of the Arno River. They belonged to Pisa in Dante’s time.

88. you neo-Thebes: Thebes was famous for bloodshed and political upheaval.

89. Uguccione and Brigata: Uguccione was Ugolino’s fifth and youngest son, and the younger brother of Gaddo. Brigata was Ugolino’s grandson and the brother of Anselm. The father of the two grandsons was Ugolino’s eldest son, Guelfo.

91–93. We kept walking and farther on came to other shades . . . Their faces, instead of bent down, were turned up: This is the third section of the ninth circle, Ptolomea (or Tolomea); it will be named in line 124. This section is reserved for those who betrayed friends and guests. Their souls are sent here immediately upon committing their crimes even though their bodies may continue to live on Earth. The name Ptolomea may have been taken from the story of Ptolemy from I Maccabees 16.11–17. In a power grab, he slew his father-in-law and his two sons, after having invited them to a banquet. In Antenora, the faces looked forward; in Caina, the faces were bent down; here in Ptolomea, the faces are upturned.

118. Fra Alberigo: Friar Alberigo (d. 1307), a nobleman from the Guelph Manfredi family of Faenza, became a Jolly Friar.

118–120. the one who ordered / Fruit from the evil orchard; here I am, paying— / With interest—an empire of dates for the few figs I served: He famously invited two family members who had plotted against him in a power struggle to a banquet. After the dinner, Alberigo ordered fruit to be served; this was the signal for assassins to come forth and stab the two guests to death. Now he says the fruits of his crime are more costly than the fruit he once served; dates in that era were imported and therefore more expensive than figs, which were local to Tuscany.

122–123. “I have no idea how my body’s doing / Up there in the world”: The date of his death is unknown but from this we can assume he was still alive in 1300.

125–126. A soul headed here often tumbles down / Even before Atropos cuts the thread: Atropos is the third of the three Fates: Clotho spins the yarn, Lachesis measures it, and Atropos ends a life by snipping it.

131. a Boilerplate, a mechanical man: Boilerplate, a character created by Paul Guinan, is a robot invented by the fictional Archibald Balthazar Champion in order to “resolve the con-flicts of nations without the deaths of men.” He is featured in the coffee-table book Boilerplate: History’s Mechanical Marvel by Paul Guinan and Anina Bennett. The term “boilerplate” more generally refers to standardized, formulaic language often found in legal documents. [ed’s note: The book has also recently been optioned by JJ Abrams production company.]

137. He’s Branca d’Oria. It’s been years / Since he crawled into this deep freeze: Branca d’Oria (d. c. 1325) was a Ghibelline nobleman from Genoa who murdered his father-in-law Michel Zanche, the governor of Logudoro, and another relative at a banquet.

149. Reader, I refused: “Reader, I married him” is a famous line from Charlotte Brontë’s novel Jane Eyre. The novel was first published in England in 1847 as Jane Eyre. An Autobiography under the pseudonym Currer Bell.

154. With one of the worst spirits of Romagna: Friar Alberigo (see note to line 118).

157. one of the living dead: “The living dead” is a broad term that today refers to zombies—fictional characters who are reanimated corpses or mindless human beings. The term was popularized by George A. Romero’s 1968 horror film Night of the Living Dead; there have since been countless sequels and spin-offs. Pythagoras used the term to describe those who lack spiritual awareness.

NOTES TO CANTO XXXIV

1. “The banners of the King of Hell come forth”: This phrase is a parody of the first line of the Vexilla Regis, a Latin passion hymn in praise of the cross by Venantius Fortunatus, bishop of Poitiers (c. 530–610); it is usually sung on Good Friday. The first stanza is:

Vexilla regis prodeunt,

Fulget crucis mysterium,

Quo carne carnis conditor

Suspensus est patibulo.Trans:

The banners of the King come forth,

The Cross’s mystery shines;

And there the builder of the earth

His sacred breath resigns.

The Reverend John Wesley Thomas interprets Dante’s parody of the line as a sting- ing rebuke of object worship. He argues that “the ancient Iconoclasts, Claudius, bishop of Turin, and probably Dante himself, were of the opinion that the adoration of the cross was the invention of the Antichrist” (346). The banners are meant to refer to Satan’s wings, just coming into view.

2. and straight at us: Technically the banners aren’t coming toward Dante and Virgil; the two men are moving toward them.

17–18. the creature / Who’d once been a pretty little love-god: Before he suffered the sin of pride and fell, Lucifer was the most beautiful of all the angels; afterward, he’s hideous. The “little Love-god” in Shakespeare’s “Sonnet 154” is Cupid:

The little Love-god lying once asleep

Laid by his side his heart-inflaming brand,

Whilst many nymphs that vow’d chaste life to keep

Came tripping by; but in her maiden hand . . .

20. Look, it’s Dis: The city of Dis begins at the sixth circle and ends at Lucifer, in the center of the ninth. In this instance, Lucifer, the ruler of the devils, is referred to as the embodiment of Dis. In the Aeneid Virgil uses the name Dis for Pluto, Greek god of the underworld.

20–21. this is the place / Where you have to arm yourself with courage: On October 16, 1793, when the Revolutionary Tribunal juror Abbé Girard accompanied Marie Antoinette to the guillotine, he reportedly said to her, “This is the moment, Madam, to arm your- self with courage.” To which she reportedly replied, “Courage! The moment when my ills are going to end is not the moment when courage is going to fail me!” Fraser, Marie Antoinette, 440.

36–37. One can see how every bit of ire, envy, and despair // Derives from him: John Milton, Paradise Lost (4.114–115):

Thus while he spake, each passion dimm’d his face

Thrice chang’d with pale, ire, envy, and despair . . .

39–45. red . . . yellow-white . . . Africa: Many commentators presume the three colors are meant to represent the inhabitants of the then-known continents: Europe (red), Asia (yellow-white), and Africa (brown). Vernon (2:634–635) notes that his father, Lord Vernon, sided with Buti’s view that red is meant to suggest Rome (and the Guelphs); black, Florence (and the Neri); and yellow-white, France (with its traditional pattern of gold fleur-de-lis against a white background). Others argue that the colors represent weaknesses: red as hatred, yellow as impotence, and black as ignorance. In any case, the satanic three-in-one is the antithesis of the Holy Trinity.

45. where the Nile begins in Africa: Ethiopia.

46–51. two enormous wings that emerged from under each . . . To create three waves of down- draft: Isaiah 6:2 speaks of six-winged seraphim: “with twain he covered his face, and with twain he covered his feet, and with twain he did fly.”

62–67. Judas Iscariot . . . Brutus . . . Cassius: These are the world’s three worst sinners: Judas for betraying Christ, Brutus and Cassius for betraying the Roman emperor Julius Caesar.

68–69. But night’s coming again / And we have to go. We’ve seen all there is to see: It’s now approximately 6:00 p.m. on the Saturday before Easter Sunday in the Northern Hemisphere (where Jerusalem is located). It has taken Dante and Virgil twenty-four hours— from Good Friday evening to Holy Saturday evening—to traverse the nine circles of Hell. The next twenty-four hours will be spent traveling from where Satan sits at the center of Earth to the point where the two men will exit from a crevice at the base of Mount Purgatory, which sits on an island in the Southern Hemisphere; both the island and its mountain were formed when rock was displaced by the impact of Satan’s fall from Heaven. When Dante and Virgil exit it will be 7:30 a.m. on Easter Monday; they will see the stars in the dawn sky.

72. Like girls gathering roses, seized the time and place: The carpe diem phrase collige, virgo, rosas (“maidens, gather roses”) is taken from the poem “De rosis nascentibus” (also referred to as “Idyllium de rosis”) by Decimius Magnus Ausonius (d. c. 395), a Roman poet and rhetorician. Edmund Spenser incorporated the line in The Faerie Queen (2.12):

Gather therefore the rose, whilest yet is prime,

For soone comes age, that will her pride delowre:

Gather the rose of love, whilest yet is time,

Whilest loving thou mayst loved be with equall crime.

The seventeenth-century poet Robert Herrick incorporated the phrase as “Gather ye rosebuds while ye may” in his poem “To the Virgins, to Make Much of Time”; the Pre-Raphaelite painter John William Waterhouse titled a 1909 oil painting Gather Ye Rosebuds While Ye May.

96. And the sun says it’s seven-thirty a.m. again: Dante says the sun has returned to mezza terza, or midway between 6:00 and 9:00 a.m.; it is therefore 7:30 a.m. Holy Saturday morning where they are in the Southern Hemisphere. Since there has been a twelve- hour time change; it is still only 7:30 p.m. Saturday evening in Jerusalem. It will take them another twenty-one or twenty-two hours to reach the point where they exit at dawn on Easter morning at the foot of Mount Purgatory. Dante’s emergence from Hell echoes the Easter Sunday resurrection of Jesus Christ.

103–105. Where’s the ice? And him, how is it he’s fixed like this, / Upside down? And how, in an hour and a half, / Did the sun move from evening to morning?: Dante mistakenly thought when Virgil turned around that he was climbing back up, toward Satan’s head. He was not. He was climbing down through the hollow that surrounds the lower half of Satan’s body (he is stuck in the ice at his waist). Dante is also mistaken about the time; it has been thirteen and a half hours, not an hour and a half. Virgil has to explain the twelve-hour time change.

110–111. But when I turned myself around / You passed the point of maximum gravity: Medieval scientists wrongly believed that the point of maximum gravity was at the center of Earth; in fact it is at the surface.

117. Judecca: The fourth and final zone of Cocytus is named after Judas Iscariot, who dangles from Satan’s middle mouth. Commentators vary on whether Judecca is disc- shaped or whether it includes the entire sphere of ice in which Satan is embedded.

130–131. But only by the sound of a stream that, / As it trickles down a slight incline: The stream is thought to be run-off from Lethe, the river of forgetfulness, in which the penitent in Purgatory have washed off their sins. Purgatorio, XXVIII, 130–132.

139. To once again catch sight of the stars: All three cantiche—Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso—end with the word stelle (“stars”), a reiterative gesture to Heaven.