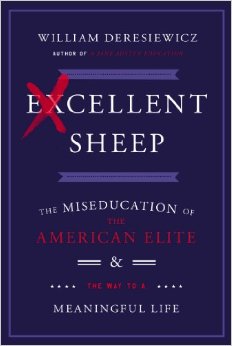

In the just-released Excellent Sheep: The Miseducation of the American Elite and the Way to a Meaningful Life, the former Yale professor William Deresiewicz rails against the system of elite higher education that formed him, and that he abetted for years. Part history, part manifesto, part cultural critique, part blistering political polemic, and part memoir, Excellent Sheep is both smart and inspiring, and has the urgency of the letters of St. Paul after the Damascene conversion. It’s one of those books that you want everyone you know to read so you can talk about it immediately. Whether or not you agree with his arguments, there are enough ideas in these 256 pages to spend a full semester discussing. In short, Excellent Sheep is a book worthy of your attention.

Deresiewicz graciously answered several pages of questions I’d prepared, in what turned out to be a far-reaching discussion:

(Greg Olear) I enjoyed your book very much. I found it both insightful and inspiring, and although it’s clearly written to young adults who are about to go, are in, or have recently graduated from college, I found it applicable to my own life as I unequivocally enter my middle age.

But I’ll admit that at times I was also anxious because my fancy-pants alma mater wasn’t mentioned. I’m sure you’re going to get criticized for being “elitist,” whatever that word means. What’s your response to that?

(William Deresiewicz) I’m glad you liked the book. I should say that it’s written not only for the young adults you mention, but also for their parents, teachers, professors—really, anyone concerned with elite higher education, which really should be everyone, because we all live in a country that’s run by people the system produces.

I guess that’s the answer to the charge of elitism. People have accused me of elitism for simply daring to acknowledge the existence of an elite and of the schools that serve it. I talk about the Ivy Leagues and their peer institutions because those are the schools that so many kids and parents, especially in the upper middle class, are obsessed with. But if it makes you feel any better, I define elite colleges as, roughly, the top 100 most selective schools. I’m sure your fancy pants alma mater is one of them.

(GO) That will make no small number of my fellow alumni very happy.

(WD) This actually goes well beyond the Ivy League. James Fallows estimates that about 10-15% of high school graduates are caught up in the competition for spots at selective schools. That amounts to something like 400,000 kids a year.

(GO) Again and again in the book, you advocate for the humanities, railing against this pervasive notion that any mode of study that does not lead itself to gainful employment is a frivolous waste of time and money. As both an English major and a novelist, I cheered…although I’ll own that the voices in my head denouncing my chosen pursuits were not quieted. So I’ll play devil’s advocate here. How can you tell an 18-year-old kid about to rack up 80 grand in student loans to study literature instead of “something useful”?

(WD) It isn’t either/or: either a liberal arts education or a specialized, vocational one. American higher education, uniquely among the world’s systems, makes room for both. You major in one thing, but you get to take lots of courses in others. Study something useful, by all means, but don’t forget that college is also about something else, something equally important.

People also need to know that the liberal arts are themselves extremely useful. “Your College Major Is a Minor Issue, Employers Say,” runs a recent headline in The Wall Street Journal. A survey of 318 companies found that 93% cite “critical thinking, communication and problem-solving skills as more important than a candidate’s undergraduate major.” Another recent survey found that 30% of companies were recruiting liberal arts graduates, second only to engineering and computer science, at 34%, and far ahead of finance and accounting, at 18%. “Increasingly, anything you learn is going to become obsolete within a decade,” Larry Summers has said. “The most important kind of learning is about how to learn.” And that’s exactly the kind of learning that the liberal arts foster.

(GO) When I was in school 20 years ago, there was a real push against “the canon,” and for what seemed like very thoughtful, sound reasons—mostly that “the canon” is the DWEM-o-sphere. And yet are also very compelling arguments why it’s “the canon.” Not only is it good, but it represents the pinnacle of human thought for much of recorded history. You hint at this in your book, extolling the virtues (and the vices) of the Gilded Age elite schools. Do you think we should bring back this sort of classical education?

(WD) Actually, I don’t argue for a return to the canon or a classical education or the Gilded Age schools. I do love the Great Books, which I taught for many years at Columbia and Yale, but I advocate for them, to the limited extent that I do, not because they represent the pinnacle of human thought (though they certainly represent a pinnacle), but because they remain the intellectual foundation of Western society.

What I really say, though, is that students should study not the Great Books, but just, great books: challenging works of literature and philosophy from whatever time or place. The fact is that the Great Books idea, the idea that college should center on a general education conducted through the study of the humanities, belonged not only to the 19th century but also to the great flowering of public higher education in America during the first two thirds of the 20th century. That is why universities turned to British literature, and later also American literature, in the first place: to create a body of work that could be studied by young people who did not learn Greek and Latin at prep school.

(GO) My freshman year, some guys were selling t-shirts. On the front were logos of Harvard and Yale and Dartmouth etc., and it read “THE IVY LEAGUE,” and that on the back it had the Hoya bulldog, and it said, “BECAUSE NOT EVERYONE COULD GET INTO [NAME OF MY SCHOOL].” Even at the time it struck me as preposterous. First, because it was absolutely not true—if any of us had gotten into Harvard, we’d have gone there—and also because it was such a naked expression of our collective status anxiety. Nevertheless they sold a lot of t-shirts.

(WD) Well, this is one of the big roots of the problem: this ridiculous status competition that exists within, largely, the upper-middle-class and that centers on where you went to college (or where your kids are going). It’s a huge waste of time and resources, and it isn’t making anybody happy or society a better place.

(GO) The single best part of college was the first few weeks of freshman year. You’re in the dorms, and everyone is required to live there, no matter who they are, so there’s this great diversity of people from all over the country and the world, and no one really knows anyone else yet, so for a fleeting period of time, it’s totally okay to just walk around, knock on doors, and meet people. There’s nothing like it in my experience in all of life, and it’s irreplicable. You talk about college as a holistic experience, and that is how it begins. Going to community college for two years and living home and then transferring in later just ain’t the same.

(WD) I agree: which is exactly why we need to recommit ourselves to making high-quality, four-year, public higher education free for everyone who is capable of taking advantage of it—instead of pouring our resources into a few schools that only a few thousand kids can attend.

(GO) When you phrase it that way, it makes it seem like our system of higher education mirrors the distribution of our wealth.

(WD) Like just about everything else these days, I’m afraid. If I can quote from the book, in reference to the selective college admissions process: “What matters isn’t how you do, but that you’ve been permitted to participate at all. The winners go to Brown; the losers go to Brandeis; the vast majority of kids, who never had a chance to play, go to Underfunded State University, or Budget Gulch Community College, or nowhere at all.”

(GO) Thank you for presenting Amy Chua, author of Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother, in the proper light. Do you know if she’s read your book? If so, I suspect she’ll be flattered rather than angry.

(WD) Ha! I hesitate to speculate on the mind of Amy Chua. She and her husband have already written another ridiculous book in the same vein, which I assailed in The New Republic.

(GO) The most inspiring line in a book full of them is when you discuss your own awakening to being part of the rat race. “I was also missing something else: the joy that comes when you stop feeling threatened by other people’s accomplishments and let yourself be open to the beauty that they bring into the world.” I’ve glimpsed that sort of joy, but I don’t feel it enough, because like most writers, I am too often consumed by “compare/despair[1. The publishing industry has its own institutionalized compare/despair machine, which it calls the Book Expo.].” Any advice on how to achieve this?

(WD) Oh, God. It’s very hard. I still struggle with it myself, though less so than I used to. It’s helped me to think about AA, how they teach you that it’s a daily struggle. You can’t deny those feelings, you can only be aware of them and try to remember how foolish they are. And then I think it’s the other thing: the more you get in touch with that feeling of joy that your envy makes you miss, the more incentive you have to let go of the envy.

(GO) I spent three semesters as an adjunct, teaching creative writing at a very nice program at Manhattanville. I enjoyed it, but I had to stop because of the huge disparity between work hours and wages. And as professors go, I was a tourist. There are plenty of really excellent adjuncts who struggle to get by, and yet collectively form the backbone of our higher education system. What can we do about this?

(WD) We need to force institutions to prioritize spending on instruction (which has hardly gone up at all in recent years) instead of the things that they have been spending money on: buildings, administrative salaries, overseas programs, etc. How are we going to do that? We can start by leveraging the unfortunate fact that schools now regard their students as customers. If kids and families started demanding real professors instead of adjuncts, colleges would have to change their policies.

(GO) Dick Durbin just introduced a bill that would eliminate student loan debt for adjuncts. Is that a step in the right direction?

(WD) I hadn’t been aware of this. Yes, it would certainly be a step in the right direction. A small step, though. We need to reverse the tide of adjunctification, not just palliate it.

(GO) On page 138-9, you write: “To question everything, to melt down the world in thought and seek to reforge it anew, was seen, for the better part of two centuries, as the duty and privilege of being young. Great changes come out of this, of which the rights revolutions were only the final chapter. The sixties were not the exception; we are.”

Then you note that “perhaps it’s no surprise that students at selective colleges feel so little distance from the system. After all, it’s working rather well for them.” The gyst here is that this new crop of kids is more conservative, in the sense of seeking to maintain the status quo, than ever before. Do you see this carrying over into politics as well? Are we graduating a bunch of Barry Goldwaters?

(WD) Absolutely not. The kind of conservatism you’re talking about is very different from political conservatism. It’s really a kind of bipartisan self-satisfaction. I think of Bill Clinton, who ratified the neoliberal or Reaganite consensus in politics, then went on to become an entrepreneur of humanitarianism in essentially the same vein: lots of high-status kids running around the world helping the less fortunate, but always within the framework of the same neoliberal idea, always working within the system instead of stepping back and trying to change it fundamentally, which wouldn’t be so good for them.

(GO) You make a similar point beautifully in Excellent Sheep, really calling out the post-Boomer generations about their political detachment. Here:

So think about the way that things have changed over the last twenty years. Think about the way they’ve changed in terms of technology and food, the areas that the culture cares about the most. Smartphones, iPads, farmers’ markets, sustainable agriculture—great, right? (Great for those who can afford them, anyway). Now think about the way they’ve changed in terms of politics and economics, the things with which the culture refuses to dirty its hands. The Iraq War, Citizens United, the financial crisis, ever-widening equality. That doesn’t look to me like such a deal. With the “creative class” is busy playing with its toys, the world is circling the drain.

Part of the issue here is, I mean, what’s to be done? As you point out later in the book, our politicians almost all come from the same elite colleges, and an astonishing number are legacies. We are all set for Bush-Clinton redux in 2016. Something must be done, sure. But it feels hopeless sometimes, which I think is why people take to Twitter. At least that’s doing something, even if it’s ultimately useless. Should we start occupying college buildings again? What do we do?

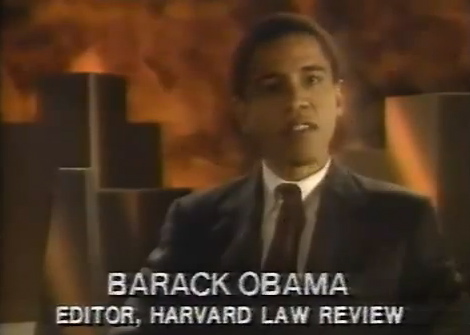

(WD) I don’t have an answer for that; I only know that we need to find one. We don’t even all need to find the same one, and it certainly doesn’t need to be (and probably shouldn’t be) the one that young people came to in the 60s (occupying college buildings, etc.). But the thing about politics is that it doesn’t go away just because you decide to stop thinking about it. There was an article in the Times recently about how people thought there was going to be an Obama generation just like there had been a Kennedy generation and a Reagan generation: that a cohort of young people would be inspired to enter politics to make the world a better place. It turns out that not only is that not happening, it isn’t even happening among his former staffers, who are all going into consulting or something like that.

(GO) There was a brief moment after Obama was elected when I thought: there’s a chance that this guy might be one of the really great presidents, an FDR for our time. Suffice it to say, this did not come to pass. He’s been a huge disappointment, I think, for almost everyone. And you propose a key reason in the book: he’s a technocrat, the exemplar of our elite higher education system—and thus not capable of the radical thought necessary to affect real change.

(WD) I think that’s true. It’s not that I don’t prefer him to the alternative—believe me, I do—and if it’s a matter of the lesser of two evils (as it pretty much always is), I’ll be out there knocking on doors. But he does exemplify a lot of the problems with the system—as do pretty much every major party presidential nominee since Michael Dukakis (albeit not all of them in the same way).

(GO) You are brave enough in the book to talk about diversity, and to say what should be obvious but remains largely unspoken: that the “diversity” we’re building at colleges and at companies after that is really people in the same socio-economic class who are of different ethnic backgrounds. Class is ignored, probably because it’s harder to quantify. I remember when Condi Rice’s inclusion in George W. Bush’s cabinet was lauded as a nod to diversity. I was like, “She’s a neo-con like the rest of them!” Why does this notion persist?

(WD) It persists because liberals stopped talking about class a long time ago and started talking about those other forms of diversity. I don’t blame conservatives for this; they would ignore all of these issues if they could. But as I see it, our new multiracial, gender-neutral meritocracy has more or less abandoned everybody else.

(GO) I didn’t realize it at the time, but that was the significance of the O.J. Simpson verdict. It showed that, for the first time, class and money and status were more important in this country than race.

(WD) Race is still important, but we also need to recognize that race is often a way of not talking about class.

(GO) That is something that has never occurred to me before, that race is often a way of not talking about class. Care to expound on that a little?

(WD) I’m not saying anything that hasn’t been said before, most notably by Walter Benn Michaels in The Trouble with Diversity. We seem to think that we’ve exhausted the issue of inequality when we talk about race, gender, and sexuality. Or at least, we used to. Things have changed of late, I think—outside of the academy, if not within it yet. But the point is, a multiracial, gender-neutral elite is just as capable of perpetuating its class position as the old WASP aristocracy.

(GO) A few times you talk about the “PhD Glut” of the 1970s, but you don’t cite a principal reason: that many of those advanced degrees were pursued as an alternative to mandatory military service during Vietnam. By the end of that war, there were more college educated Americans than ever before. Do you think that this has anything to do with the income disparity that has only widened since then?

(WD) You’re mistaken about the history. More people went to college because of Vietnam, and maybe a few more went to graduate school, but Vietnam was over in 1973, when the PhD glut was only getting started. The real reason for it has to do with the end of the postwar boom in higher education. From 1949-79, the number of students more than quadrupled, the number of faculty nearly tripled, and institutions were established at a rate of almost one a week. That all came crashing to a rather sudden halt as the baby boom started to age out of college and states started to withdraw funding for higher education. The one thing that didn’t change was the production of PhD’s. Hence the ongoing glut.

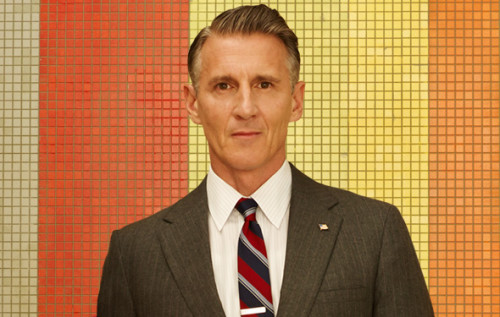

(GO) I live in upstate New York, in a town with a state university no less, and I did not know until your book that Nelson Rockefeller of all people was responsible for setting up our higher education system. Here’s a guy who was unquestionably conservative—his drug laws are repressive and ill-conceived, for starters—and wealthier than almost anyone, and he thought it was his responsibility to give back. That means that today’s crop of wealthy arrivistes are more conservative than Henry on Mad Men. What gives?

(WD) What gives is an enormous shift since the postwar decades in the way we think about society and ourselves in relation to society. Rockefeller wasn’t actually conservative, however ill-conceived his drug laws were. He belonged to that species that used to be known as liberal Republicans. The point is that there used to be “the liberal consensus”: that the best way to structure society was through a mixed economy—some public, some private, with the public regulating and taxing the private for the sake of funding public goods. Then came Buckley and Reagan, and now we have what might be called a conservative consensus. That’s why Clinton looks more conservative then Rockefeller, and maybe even Nixon. We need to start pushing back. It’s going to take a long time (it took a long time for Buckley and Reagan), but we need to start.

(GO) Cut to Nixon, rolling in his grave.

But seriously, it is astounding to me how many people in this country vote against their own interests. For example, the states whose governors have refused federal aid for Obamacare tend to be, economically, the states who need that aid the most. I think this ties into the higher education system, for reasons you point out: the beneficiaries of that system, who are collectively running the country, are in no hurry to change it.

(WD) True, but I think we need to be wary about deciding that people are voting against their own interests. I see a large pattern that goes beyond the United States to places like Eastern Ukraine or rural Thailand. We blame people for resisting what we call progressive, liberal reform, voting for conservative, nationalistic parties (including the Republicans). But the fact is that liberalism now largely means neoliberalism. Those people aren’t going to benefit from Westernization (or what we might call, in this country, Northernization). They’re simply going to get eaten alive by urban, liberal elites.

(GO) Maybe. But they’ll pay less for health insurance.

You talk about the ridiculous gap in taxation levels—George W. Bush went to war, twice, and still cut taxes on the rich; he was supposed to be the education president but he obviously sucks at math—and all the lost revenue that should have been collected: “as far as I’m considered,” you write, “that money belongs to the rest of us.” How can we get that to happen? Why are people in the United States so afraid of socialism? And wherefore this bizarre theory that Obama is a socialist?

(WD) Forty years of right-wing propaganda accompanied by 40 years of liberals essentially avoiding the issue of class. From the Progressive era through the New Deal and the Great Society, we built what essentially was (or at least was in the process of becoming) a social democratic state: high taxes, high public spending, diminishing inequality, increasing prosperity. We can get back there, but it’s going to take not only political organization, but also intellectual mobilization. The left needs to rebuild its stock of ideas.

(GO) I’m not sure what you’re working on next, but might I suggest writing a manifesto proposing a new stock of ideas for the left? That’s something I’d really want to read.

(WD) Ha! Like so much I talk about in the book, this needs to be a large, collective project, and it’s going to take a long time.

I can’t say enough about this piece. It made me furious, excited, happy, depressed, invigorated, provided a sense of solidarity and exacerbated my alienation. For starters. In other words, it did what any piece of great writing does. Can’t wait to read Deresiewicz’s book, as I suspect it will be a tilt-a-whirl of the emotions expressed above.

His book is great, Sean. It’s almost like taking a really engaging class.

Thanks so much for the kind words.

http://nymag.com/daily/intelligencer/2014/08/cornel-west-and-the-insular-obama-hating-left.html

There were a few people I kept thinking of while reading the book, good sir, and you were one of them. Read it. I’m curious what you’ll think.

Obama’s got two years left. A lot can happen in two years. I wanted more, much more, especially with regard to banking and the financial crisis, but his accomplishments are not unimpressive.