“COLOR IS CONSCIOUSNESS itself, color is feeling,” says William H. Gass in On Being Blue, and these qualities are “alive in time like the stickiness of honey or the rough lap of the cat, for color is connection.” His diminutive book on the color blue, first published in 1976, is alive with all kinds of connections, and provokes a range of feelings, in spite of its stated adherence to just one segment of the spectrum. On Being Blue was reissued earlier this year as part of the New York Review of Books Classics series, garnering a whole new generation’s worth of attention and praise, but not all parts of the book stand the test of time. Beneath its somewhat abstract premise, Gass reveals (and willingly recycles via quoting) the same sad, faded phallocentric proclivities as his generation of male American writers.[i] But before I give you, ahem, a blow-by-blow description, I’d like to talk a little bit about Gass the man; the field of color literature, particularly books on blue; and to trace a little bit of the context in which the book was produced.

Gass, now almost 90 years old, is a major figure in American literature – a novelist, poet, and critic, positively dripping with awards. You might call Gass a writer’s writer given his interest in the very unit of the sentence like his recently published collection of essays Life Sentences (2012). Gass was also a philosophy professor for many years, which is perhaps why he subtitles this book “A Philosophical Inquiry,” and indeed, he deals rather deftly (and swiftly) with the color theories of Plato, Democritus, Epicurus, Descartes and Schopenhauer. But above all, this was the first and, some might argue, the finest exponent of subjective color literature – writing which is a deeply idiosyncratic response to the spectrum of hues that surrounds us, seeping into our art, language, and dreams. Gass didn’t write a book of optical theory, or a book suggesting links between your favorite color and your personality type. He wrote about his particular, personal take on one color – blue – in order to see just how far that simple premise could lead him, for blue is the talismanic force which goads each sentence and binds the book together, it is “the color consciousness becomes when caressed; it is the dark inside of sentences, sentences which follow their own turnings inward out of sight like the whorls of a shell, and which we follow warily…”[ii]

There have been a plethora of books about one or other aspect of color over the years, starting with the scientific classics – Isaac Newton’s Opticks and Goethe’s Theory of Colors, which most color writers (including myself) dutifully skim, and then sagely reference. Artists, naturally, have a lot to say about color (Van Gogh, Matisse), and even philosophers tackle the subject (see Wittgenstein’s laconic, epigrammatic Remarks on Color, written in 1951). Then there are mid-twentieth century pop-science tomes like Color Psychology and Color Therapy, in which color “expert” Faber Birren ruminates on the auras of “savages.”

Gass was clearly a game-changer, and ahead of the pack – almost twenty years had passed before Alexander Theroux published first The Primary Colors, and then The Secondary Colors; essays filled with free-associations on individual spectral hues in a pre-Google, encyclopaedic frenzy. Around the same time in the early 90s, Derek Jarman penned Chroma, his poignant personal farewell to color and thus to life, as he first went blind, then eventually died due to AIDS-related complications. Significantly to the theme of blue, Jarman’s filmic swansong was called just that, Blue, featuring nothing but the last color he could see before the eternal dark descended – a deep blue screen for 79 minutes, with a soundtrack full of loss and longing, but also searing moments of joy.

http://youtu.be/wVaC3XKSi5M

For the next few years, color seemed to have slipped from the agenda, until Scottish artist David Batchelor released a brilliant little book called Chromophobia in 2000, in which he accused Western culture, including, even especially, the contemporary art world, of being fundamentally anti-color. Perhaps in order to disprove Bachelor’s argument, a subsequent smorgasbord of books emerged, exploring the evolution of pigments and dyes, and tracing socio-historical currents of color. [iii] Contrary to Batchelor’s thesis, color was also back on the contemporary art agenda. There were major exhibitions focusing on aspects of color with their attendant showy catalogues, such as Color After Klein (2005) and Color Chart (2008). The art and culture magazine Cabinet began publishing their wonderful “Colors” column, in which a different writer for each issue is given a random hue as the spark for some free-ranging text. Batchelor returned to the scene in 2008 as the editor of Colour, part of a series released by London’s Whitechapel Gallery dedicated to issues in contemporary art, and filled with all the pertinent quotes by philosophers, artists and writers (including Gass) about everything you could ever possibly want to know about the spectral stuff. Of course, the reissue of Gass’s book is all part of this color-saturated zeitgeist, and as I write, there’s a show on now at the Kunsthalle Wien called Blue Times.

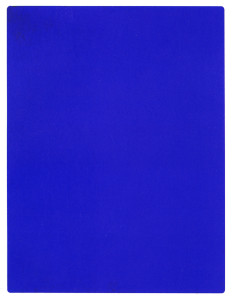

IKB 191, aka International Klein Blue, a painting of Yves Klein’s made with his patented color which was IKB was developed by him and chemists at pharma co Rhône Poulenc.

Color is the ultimate leveler – everyone has an opinion, and this is perhaps why the books continue to proliferate. Anthropologist Michael Taussig wrote What Color is the Sacred? well aware that “color is full of kitsch traps” and that color makes fools of writers because “it allows us to say the first and, after that, the many things that willy-nilly enter our head and make us feel dizzy with profundity touching on the theological.”

I tried to write like this myself in my own take on color, A Rainbow Reader, in which I free-associated on each of the spectral hues, never for a minute worrying that it had all been done before. For as Jarman wrote, “I know that my colors are not yours. Two colors are never the same, even if they’re from the same tube.” Maggie Nelson, aware that she’s not the first or last to do so, defends her own decision to write about her personal relationship with the color in Bluets from 2009:

“It does not really bother me that half the adults in the Western world also love blue, or that every dozen years or so someone feels compelled to write a book about it. I feel confident enough of the specificity and strength of my relation to it to share. Besides, it must be admitted that if blue is anything on this earth, it is abundant.”

When I was researching blue for A Rainbow Reader, I somehow missed the plethora of women’s writing on this most ubiquitous of colors. All I saw was Burroughs, Genet, Gass, and Jarman: a cocktail of cops, cocks and blue jeans. I announced the color altogether too masculine for my taste, grumbling my way through the chapter, and the book went to press last year. But this year’s re-release of Gass’s take on blue prompted me to see if there were any specifically feminist takes on this boy’s-own color, and I wasn’t disappointed. Nelson’s book Bluets is as poetic, as diminutive, and as sassy as Gass’s, without the craw-sticking moments of misogyny.[iv] Bluets is epigrammatic – written in perfect bite-size chunks, like Gass’s pebbles shaped into syllables, like the “sucking stones” sequence from Samuel Beckett’s Molloy, a pleasantly non-misogynistic passage which Gass gives high praises, or Virgina Woolf’s pockets full of rocks, in which she walked to her drowning, and now walks her way into and out of Nelson’s text. Nelson’s fragments form traces – like Hansel and Gretel finding their way out of the forest – or accrete into small heaps of sadness and pain, but also of incredible defiance, with an electric blue energy that jolts the reader out of complacency.

There are also illuminating blue passages in Rebecca Solnit’s A Field Guide to Getting Lost in which the writer argues for an aesthetics of wandering, and frequent excursions into “The Blue of Distance.” In The Anthropology of Turquoise, nature writer Ellen Meloy wrote about her Four Corners desert home with passionate metaphysical fervor, mining the sacred stone for all its stories: geological, cultural, and sensory. And, just as my own book was coming out, another woman released another book on her love for the color: Blue Mythologies by the art historian Carol Mavor. Both Nelson and Mavor compare themselves to satin bowerbirds, Mavor to the male, as she is the collector of blue; Nelson to the female, for “When I see photos of these blue bowers, I feel so much desire that I wonder if I might have been born into the wrong species.”

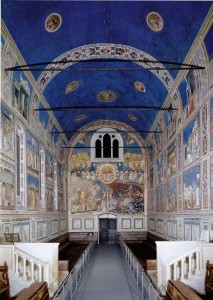

Of course, this ubiquity, this abundance of colored text that Nelson talks of, means that many of the same sources get recycled, ad infinitum. Many of us blue ladies (Gass might have pejoratively called us Bluestockings) plucked facts from the French color historian Michel Pastoureau and wove them into our blue-tinged reveries, and we all mentioned those usual suspects of blue, Yves Klein and Derek Jarman.[v] We all quote from Julia Kristeva’s essay on “Giotto’s Joy” from Desire in Language, in which the feminist philosopher unpicks the mystical blue of Giotto’s Padua Chapel, only to say that color is “the laying down of One Meaning so that it might at once be pulverised, multiplied into plural meanings” which is, I suppose, what Nelson and I, and even, or especially, Gass, were all trying to do.

Giotto’s frescoes in the Scrovegni Chapell in Padua, ca 1300.

Generation and gender means that Gass’s take on blue is unique, though not unimpeachable.[vi] It’s also written around the time that Nixon resigned his office at the White House rather than face certain impeachment, so it’s no wonder that there’s a pall of disillusion, of cynicism that hangs over the work: the Watergate Scandal was all over the news. The Summer of Love seems a world away, while the Vietnam War only recently ground to a halt. Feminism is on the rise, and while Gass was a staunch fan of Gertrude Stein, writing hallmark essays on her work, he seems to have less sympathy for what he calls the “prick-skinning women” of the mid-70s.

Gass announces all the avenues his blue book could follow, for blue is “pedantic, indecent and censorious” and many more things besides. While he does deal with color perception and philosophy, and even sadness, the twin themes that predominate throughout On Being Blue are sex and the written word, and the inevitable relationship between the two.

Gass begins this adventure of letters with a memory of the blue-covered “Little Library” books that he read as an adolescent, “hoping for a cock stand.” There is a pleasing circularity in the fact that we, too, are holding in our hands a small blue-covered book, which whispers from the outset of the erotic potential of blue. Gass is blunt from the get go: “We always plate our sexual subjects first. It is the original reason why we read… the only reason why we write.” True or not, this dance of desire with words keeps us guessing which of the two is closer to Gass’s heart – or crotch. He talks of “the use of language like a lover… not the language of love, but the love of language, not matter, but meaning, not what the tongue touches, but what it forms, not lips and nipples, but nouns and verbs.” The very rhythm of the sentence, the way it juggles oppositions like cupping breasts, while encouraging our tongues to tiptoe outside our mouths and read aloud, proves the tactility of language. Like a lover, Gass seems to beg us to vocalize these pleasures of the text. Yet, “It’s not the word made flesh we want in writing, in poetry and fiction, but the flesh made word.”

While Gass is not averse to rattling off a list of blue-colored stuff (indeed he opens the whole affair with “Blue pencils, blue noses, blue movies, laws, blue legs and stockings…”), he selects several of his favorite passages of fleshy words, not because they are blue-hued, but because they are blue as in mildly pornographic, the sort of thing, we assume, that gave the adolescent Gass a cock stand. But here is where I part company with him, for what he finds titillating just gives me the blues; his cerebral cock seems to stand tallest for tales of rape and abuse. Gass chooses to analyze the prose of the rape scene of the “whoreship” Cyprian in John Barth’s Sot-Weed Factor (1960), as well as alluding to the rape of Temple Drake with a corncob in William Faulkner’s Sanctuary (1931). A woman gets badly beaten in John Hawkes’s The Lime Twig (1961) and Gass says matter-of-factly “This passage is impossible to overpraise…an example of total control.” He repeats phrases from this description of a sadistic beating as though picking morsels from his teeth, delectating the afterglow of a fine repast. Later, he concedes that “It wasn’t nice of Thick to beat Margaret,” and “I really don’t know if he did it beautifully or not” (spoken as though there was potential for such a thing as a “beautiful beating”), “but Hawkes’s account is beautiful.”

I gain no aesthetic pleasure from the violence of these passages, they make me wince and set off explosions of blue-black bruises in my feminist cortex, like fireworks in negative. And it’s quite clear that Gass has no time for feminists. While pontificating on the patois of the penis, he says “…in a world of prick-skinning women, perhaps a twanger is what one needs. These days are drear.” Strange that he should feel the mana of his member under threat from flagellant feminists, when the character Thick uses his “truncheon as a penis” while, in Sanctuary, “Temple Drake begins to bleed.” Stranger still that Gass doesn’t follow his own advice to avoid violent language. He says, “The wise writer watches himself” (of course, the writer is a he), “for with so much hate inside them – in ‘bang,’ in ‘screw,’ in ‘prick,’ in ‘piece,’ in ‘hump’ – how can he be sure he has not been infected – by ‘slit,’ by ‘gash’ – and his skills, supreme while he’s discreet, will not fail him? Not an enterprise for amateurs. Even the best are betrayed.” Indeed.

While Gass does mention Mansfield, Woolf, Colette and Stein, there’s an assumption throughout that the reader, like the writer, is male, and that even as he countenances female agency, he does so from the perspective of the patriarchal, missionary-position male, noting that during sex, “the body of the beloved… alters under us…escapes our authority and powers.” And again, “If I say, to the lady lying under me, ‘hurry up, please, it’s time,’ I am quoting, and my fucking may be quoting, too…” (italics mine).

In spite of all this writerly virility, there is a recurrent loathing for the facts of female sexuality, viz “the acidulous salts of the vagina,” although at times it can be beguilingly humorous, such as “Ellen’s merry-whiskered friend” or words like “quim” – vulgar Victorian for vagina. Gass seems to love coinages which sound faintly naughty, like quint and quink. He laments our “impoverished” vocabulary, and has tried to introduce the following neologisms: “‘squeer,’ ‘crott,’ ‘kotswinkling,’ and ‘papdapper,’ but without success.” In today’s landscape of rapidly diminishing linguistic diversity, there is a sense of the quaint, the quirky, even the Joycean in Gass’s prose, as in, made to be read aloud, as Jarman’s thoughts on blue were read aloud over the vast blue screen.

It’s Gass’s intimate care for words, if not for women, that redeems On Being Blue, as for example when he ponders the way in which “Children collect nouns, bugs, bottlecaps, seashells, verbs: what’s that? what’s it doing now? who’s this? and with the greed which rushes through them like rain down gulleys, they immediately grasp the prepositions of belonging and the pronouns of possession. But how often do they ask how cold it is, what color, how loud, rare, warm, responsive, kind, how soft, how wet, how noxious, loving, indiscreet, how sour?”

There’s a supreme bathos in Gass’s writing about the miracle of language, “when in your mouth teeth turn into dragons and you do against the odds what Demosthenes did by the Aegean: shape pebbles into syllables and make stones sound,” only to use that gift for cheap thrills. With disarming honesty, Gass notes that “my desire for another man’s wife commingles with the disgust I feel at my taste for flaccid boobs…” Imagining himself to possess the power of invisibility, he laments, “What good is my peek at her pubic hair if I must also see the red lines made by her panties, the pimples on her rump, broken veins like the print of a lavender thumb, the stepped-on look of a day’s-end muff? I’ve that at home.” Amazingly, the book ends with a dedication to his wife!

From the day’s-end muff, to the day which begins badly when “the morning prick is limp,” Gass is blue about real-life sex, which is perhaps why he is so inexorably attracted to the printed word, where we can “continue to drain through the cunt till we reach metaphor…” He writes this in relation to a passage from Henry Miller’s Tropic of Capricorn. It says something about the other quotations Gass chooses, that the oft-called misogynist machismo of Miller seems altogether empathetic by comparison.

Reading Gass makes me tired and sad, and also unsure of my reaction to his hurtful fantasies. I second-guess the response of Gass and his macho cadre – I’m a prude, a small-boob prick-skinner with squashed-muff syndrome. If I were better looking, I wouldn’t have these issues with patriarchal literature, because I’d be spending all my time with my legs behind my head, and then everyone would be happier. Right? Or else, I would be patted on the head and placated with that gem which I occasionally have recourse to myself, “It doesn’t matter what the words say, but how they say it.”[vii] Perhaps it’s that despite Gass’s supremely self-conscious style (he is known for having taken 30 years to write a novel) sexism seems to emanate out of the gaps in this book like body odor – an unconscious production, excusable as a “sign of the times.” This personal response is not intended to vilify Gass but to beg for vigilance in our reading and writing, and in particular to contextualize the resuscitation of past texts. All the discussion surrounding this particular reprint seems to manifestly avoid any discussion of sexual politics.

Perhaps, after all, my lingering malaise over On Being Blue is true to the color: all those who write about blue seem to be in agreement about its ineffability (although Gass tries very hard to eff it)[viii]. Kristeva notes that blue is always the limit case of human perception – the last color our developing eyes learn to see, the last color left at the bottom of the ocean, the first color that emerges out of darkness, etc… while Solnit writes about the fact that distant landscapes dissolve into blue light – but, like the rainbow, elude capture, so you can never find this mythical place of blue. Therefore, blue automatically represents desire and longing for the things you can’t have. For Gass and Nelson it is nothing short of celestial – Gass calls blue “the godlike hue” while Nelson sees “all the shreds of blue garbage bags stuck in brambles, or the bright blue tarps flapping over every shanty and fish stand in the world,” as “the fingerprints of God.”

I guess with a sigh that Gass’s misogyny is (somewhat) redeemable, since we forgive “genius” every time, just like we do for Johannes Brahms and James Brown and everyone in between. Like a peahen appraising the eye feathers of a peacock’s shimmering fan, I remain a sucker for verbal sheen. But after feasting on Taussig, Meloy, Solnit and Nelson, I’m no longer sure that Gass has the brightest blue feathers on the block.

[i] From John Updike’s Couples, to Philip Roth’s Portnoy’s Complaint, to James Salter’s A Sport and a Pastime, the novels of the late 1960s and early 1970s lived out a very one-sided version of the sexual revolution.

[ii] In this sentence Gass seems to be agreeing with a quote by Kandinsky which he mentions later, that blue ‘moves into itself, like a snail retreating into its shell, and draws away from the spectator.’

[iii] Simon Garfield’s Mauve: How One Man Invented a Color that Changed the World (2000); Michel Pastoreau’s Blue: The History of a Color (2001); Victoria Finlay’s Color: A Natural History of the Palette (2002); Philip Ball’s Bright Earth: The Invention of Color (2003); Amy Butler Greenfield’s A Perfect Red (2005) – and all of this without mentioning the bubbling vats of books on Indigo.

[iv] Although Nelson does provide me with more evidence of blue’s phallic aura when she notes that one of Viagra’s side-effects includes seeing the world with a blue tint, and that this “has something to do with a protein in the penis that bears a similarity to a protein in the retina…”

[v] I do learn something new, however: from Solnit that artist Yves Klein, with his leaping from windows and judo obsession, was on speed all the time, hence his early demise in 1962 at the tender age of 34, and from Nelson that Jarman’s hero Wittgenstein, who he made a beautiful biographical film about, also wrote his book on color when he was dying, of stomach cancer in 1951.

[vi] Which reminds me, the poet Lyn Hejinian wrote on cyan in Cabinet’s “Colors” column, noting that cyanide is blue but has a peach-blossom odor, and can be extracted from the oil of bitter almonds which are in the peach family.

[vii] Maggie Nelson, my new hero, hits back at Gass in Bluets: “After asserting that the blue we want from life is in fact found only in fiction, he counsels the writer to ‘give up the blue things of this world in favour of the words which say them.’ This is Puritanism, not eros. For my part I have no interest in catching a glimpse of or offering you an unblemished ass or an airbrushed cunt.” Nelson refuses to choose “between the blue things of the world and the words that say them.”

[viii] See Samuel Beckett’s Watt, 1953 “What we know partakes in no small measure of the nature of what has so happily been called the unutterable or ineffable, so that any attempt to utter or eff it is doomed to fail, doomed, doomed to fail.”