SEVERAL WEEKS before the revelation that he wasn’t actually dying, I asked my father if there was anything he’d like to do before he died. He was at that point nine months into treatment for intestinal cancer. We were seated at our cluttered kitchen table, in the housing projects of De Land, Florida, going over his will again. It was clear he enjoyed the solemnity of discussing his own death, so once a month we would take time to imagine life without him; as a drug addict and failed pastor who lost custody of his five children, occasions for him to feel important were seldom. In any case, the process of parceling his possessions took only a few minutes because he owned nothing, and as the eldest of his five kids—the heir to his, um, empire—it was important I understood his wishes.

After deciding who would inherit his toaster and A/C window unit, I asked if there was anything he’d like to see before he died. Jerusalem? Varanasi? The Grand Canyon? For someone who had lived his entire life within a thirty-mile radius, there surely must be something out there worth seeing. The question seemed to distress him. It was as if he’d never thought of it. He pondered for a moment and said he’d get back to me.

Then the next day he told me, without a trace of irony, that his dying wish was to go to the Holy Land Experience, a Biblical-themed amusement park in Orlando. He wanted to “get close to God.” I was staggered. It takes a brilliant mind to dream up such a lazy way to heaven.

(Disclaimer: I am no man of prayer, but I respect one’s freedom to enjoy a turkey leg in the HLE’s re-creation of a first century market. Though distasteful, I think a song-and-dance interpretation of Jesus’ death is a harmless way to spend an afternoon. It might even be spiritually fulfilling—in the way Doritos fill an empty belly. I intend not to disparage everyone who goes there, but more specifically my dad and his dubious, half-assed idea of spiritual endeavor.)

My first response was laughter. Irreverent, condescending laughter. The entire idea of a Jesus-oriented theme park is inherently funny. In a land where the Pope is Mickey Mouse, they’ve built an oasis of Judeo-Christian values. A few miles from International Drive—Orlando’s mecca of unbridled consumerism—sits the world’s largest indoor replica of Jerusalem, replete with a model of the Holy Temple, where, according to the Bible, Jesus chased away the moneychangers for sacrilegious profiteering. Of all the places to find heaven, this had to be the least likely.

The point of pilgrimage, as I understood it, was to get closer to what’s real. Forty-five million tourists a year go to Orlando not to find reality, but to escape into fantasy and simulacrum. Escapism is its creed. I began to wonder if my dad could distinguish between a life-changing epiphany and a pleasant afternoon at a theme park.

But the more I thought about it, the sadder it became. A transcendent religious experience requires effort. One must get dirty when digging for treasure. A pilgrimage is a journey to the root of one’s faith, in search of something ancient and pure and indelibly true; to see with one’s eyes the very place where these spiritually enriching stories occurred—events upon which one’s entire life and worldview is based.

I imagined my father in white shawls, among the pilgrims thronging the streets of Bethlehem, awaiting the kiss of divinity.

But, alas, my father is a very lazy man.

~

I’m sure if you asked him, my dad would say his happiest moments were when his children were born. That’s a default human response, like thanking God for your Emmy. But I was with him the day he received his first Social Security Disability check. Never before have I witnessed such uninhibited joy. He cried and shook me by the shoulders and embraced me. Then he took me to Denny’s to celebrate. After a few decades of menial labor, he had received the greatest blessing of all: free money from the government. He would never work again. A Grand Slam was in order.

Officially, he was disabled because his bipolar depression made him unemployable. This might be true. But in practice, he was unemployable because he was high on crack cocaine, among other things. The SS checks enabled him to lead his preferred lifestyle: a wild binge for the first week of the month, followed by three weeks of withdrawal, terror and self-loathing.

As you can imagine, this routine makes being a father difficult. We kids enjoyed an unsupervised, frontier lifestyle for a few years. I was 12 and my own chaperone, essentially. Teachers began to notice the squalor in which we lived, and before long the Department of Children and Families intervened to relieve him of his duties. My younger siblings moved in with my grandparents and have lived there ever since. I began the circuit of foster homes, detention centers and orphanages that defined my adolescence. Eventually, I exhausted my options and ended up right where I started: living with my dad, in the projects of De Land.

Just as I began to truly resent him, he was diagnosed with polyps in the duodenum area of his small intestine. Cancer is the bane of my family, having claimed scores of aunts, uncles, and cousins. We Neighbors are raised with the fatalistic certainty that it will find us. Why improve one’s life in the face of such heinousness? Why start jogging, for instance, when you can never outrun the ultimate Olympian, cancer? Overwhelmingly, the Neighbor response has been drug abuse, the shirking of social responsibility, and suicide.

So it was no surprise that cancer had come to claim another. In the months that followed, my father’s life became an endless itinerary of doctor’s visits. Several times a month, either my aunt or grandmother or I would drive him to Orlando or Gainesville to meet with specialists. He consumed ever-increasing volumes of medications: painkillers, uppers, downers, anti-depressants. His hair thinned and he gained a tremendous amount of weight. Often, I would wake in the middle of the night to the sound of him puking, and would have to drive him to the emergency room. His illness became mine as well; my grades plummeted with the stress.

Hospice, normally reserved for people in the final stages of illness, was called in. It seemed premature; hospice is something you summon in the ninth inning, not the third. Our apartment began to resemble a distribution center for medical supplies: tubes, syringes, strange beeping machines whose function was unclear. I particularly remember something that looked like a walker, the type an elderly person might use, but in the center was a toilet seat. In case you could not make it to the commode, you could sit right there and shit.

Knowing my dad, I was skeptical. He relishes pity. And because he was seeing so many different doctors so often, none of us knew the real extent of his illness. We took the appointments and prescriptions and equipment as evidence that his ailment was something other than an elaborate ruse. It had to be, right? Certainly our medical system is competent enough to prevent people who aren’t really sick from receiving tens of thousands of dollars worth of unnecessary treatment, right?

Throughout this my dad was adamant that he would not just lie down and accept death. He was going to fight this thing, he said. He gave me several rousing speeches peppered with filched movie quotes to impress his courage upon me. For a while, he began to resemble a good man who had been dealt a bad hand. For the first time in many years, we saw the elementary spark of decency in him. I think we all felt good believing this was real.

~

I later came to know that the Holy Land Experience is owned by the Trinity Broadcasting Network, a titan of evangelical programming. We’ve all seen the pastors on television preaching before a full stadium of believers, performing miracles with the wave of a hand. The Praise-a-Thon fundraising drives. Yeah, that’s them. Their roster of charlatans boasts household names like Billy Graham and Bishop T.D. Jakes, the motivational speaker Joel Osteen, and faith-healer Benny Hinn; perennially popular programs include the 700 Club with Pat Robertson and Praise the Lord, the station’s flagship show, which is filmed in the Church of All Nations, at the Holy Land Experience.

The network was founded by Paul and Jan Crouch in 1973. They are vocal proponents of what is known as Prosperity Gospel, which maintains that God rewards people financially for making contributions to the church. It is commonly called the “health and wealth” doctrine. According to this understanding of the Bible, being rich is a sign that one is favored by the Almighty. Though Jesus was an advocate for the meek and the downtrodden, in Prosperity Gospel, the poor are afforded no sympathy. The Have-Nots should pray harder. And the logic creates a circuit: The wealthy have more disposable income to donate, and can thus accrue more blessings. It’s like compounding interest.

Such shameless tricks are not novel. Oral Roberts, a famed Pentecostal televangelist, claimed in 1987 that God would “take him home” if he failed to raise eight million dollars in donations. But the Trinity Broadcasting Network has refined the process, becoming a financial juggernaut over the last decade.

Here’s Bishop Clarence McClendon, on his show Take it by Force: “Some of you are wrestling with debt that you cannot pay off. God told me this morning to tell you to…sow a seed on that credit card that you want God to pay off… Get Jesus on that credit card! Make a pledge on that credit card!” He then promised that God would make the debt disappear within 30 days.

Or take Mr. Crouch himself, on Praise the Lord: “Have you got something that you have been praying about for 10, 15, 20 years? You have been praying for it and haven’t gotten it… It could be that you haven’t gotten it because you are a tightwad and you haven’t given your 10 percent.”

The Trinity Broadcasting Network sees the relationship between God and man in almost mechanical terms, where donating money is like pressing God’s blessings button. Pastor Creflo A. Dollar (seriously, that’s his name) has described it as a contract with the Almighty. As Mr. Crouch explained: “When you give to God, you’re simply loaning it to the Lord and He gives it right on back.” On numerous occasions, he has told stories on-air of seriously indebted people who made donations, only to mysteriously receive a check for several times that amount. In Prosperity Gospel, it is really this easy: Give us your money and God will give you the Lexus you’ve always wanted.

And the message is working. Revenue for the Trinity Broadcasting Network in 2010 alone was over 175 million dollars. It has nearly 830 million dollars in assets. And because it’s a religious organization, its income is tax-exempt. The TBN empire now includes five television stations, a theme park, a movie studio, and Trinity Music City, an entertainment complex on Conway Twitty’s former estate. Mr. and Mrs. Crouch personally fetch a combined salary of $764,000 per year. They own 30 homes and have access to the network’s private jet. If wealth is a reward for piety, they’ve clearly put in some serious praying time.

Dear Reader, I’d like to direct your attention to a few passages in the Good Book itself, passages which may have eluded the folks at the TBN:

Matthew 6:24: No one can serve two masters. Either you will hate the one and love the other, or you will be devoted to the one and despise the other. You cannot serve both God and money.

1 Timothy 6: 9-10: But those who desire to be rich fall into temptation, into a snare, into many senseless and harmful desire that plunge people into ruin and destruction. For the love of money is a root of all kinds of evil.

Mark 10:25: It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the Kingdom of Heaven.

The message seems pretty unambiguous: Beware of money because it will make you an asshole.

Of course, in Prosperity Gospel, the Bible is pruned of its anti-materialist passages and seamlessly blended with the glorification of Gatsbyian success that is distinctly American. Through this clever interpretation, piety and prosperity become bedfellows, and the rash self-interest of Adam Smith becomes one with Jesus’ altruism. I can only imagine how different the Bible would have been if Jesus had been rational about His self-interest.

So what initially appeared to be a paradox—a replica of the Holy Land in money-worshipping, consumerist Orlando—may be perfectly consonant seen through the prism of Prosperity Gospel.

~

We were in Miami visiting a doctor when I found out my dad didn’t have cancer. Up until then, we had only heard pieces of the story from different doctors; most of what we knew was what my dad reported. I was eager to hear just how bad his condition was. I even brought a notebook and pen to be sure I wouldn’t miss any important dates or instructions.

While it was true that my dad had polyps in his small intestine, they were not yet cancerous. The doctors were aware of our family history and were considering preventative surgery, but first my dad had to lose a great deal of weight. True to form, he preferred to undergo gastric bypass surgery—an expensive, dangerous and, in his case, completely unnecessary operation—as opposed to any meaningful regiment of diet and exercise.

The doctor told us explicitly that my father didn’t have cancer and that the surgery would be preventative. Then he told us again, because clearly my dad didn’t understand and kept asking silly questions under the assumption that he really was dying. The doctor was noticeably annoyed; I think he suspected (correctly) that he was being hustled. Then he told us there was a 40 percent chance of complication in the gastric bypass. He instructed my dad to see a dietician to help him prepare for the operation and the changes in lifestyle he would have to make to ensure it would be successful. This was all good news.

I wrote in my notebook: “Forty percent chance of complication.”

When we returned, we gathered the family around the table at my grandparents’ house to deliver the news. My sisters were hugging each other in anticipation. My grandfather—probably the single toughest person I know—fidgeted with his pipe, bracing for the worst. Then my dad says, straight-faced, that the doctor told him there was a 40 percent chance that he would survive the operation. The cancer was real bad, he said, but he was going to be strong and fight this.

To this day, I am unsure whether he was tactlessly manipulating the family or he genuinely believed he was dying. The truth is probably in the middle. In any case, I immediately interrupted him. You are not dying. You don’t even need this surgery, really. There’s a 40 percent chance of complication, not survival. I then told the entire family that I suspected this was a con to get drugs. The ruse was up.

The appeal of his plan was clear: sell his prescriptions at a profit and continue his addiction to crack, all the while eliciting pity from his family. He could even be thought of as courageous in his confrontation with cancer. It was brilliant. Meanwhile, my family grieved for his impending death.

After that revelation no one trusted him. His veil of heroism had been shredded, revealing a lazy, drug-addled, unlovable bum. No more speeches quoting Braveheart. No more teary-eyed discussions of who will inherit his toaster when he dies. Our reservoir of pity and goodwill had been taxed to exhaustion. All that was left was contempt.

And there was no resolution to his cancer story, either. He just stopped. No more doctors, no more medicine. No gastric bypass. Nothing. I wonder if even he realized, finally, it was all bullshit. With no one left to con, he was free to pursue his preferred lifestyle without pretense. If he wasn’t really dying, he was going to do his best to live like he was already dead. Things got real weird and I moved out shortly thereafter.

What to do with our brief time on Earth? I cannot think of a question more difficult to answer. In retrospect, I see that the promise of an impending death had solved that riddle for him. For a man with no ambitions, no dreams, no talents, a heroic battle with cancer imbued life with meaning. It gave him direction and purpose and, in a sick way, allowed him to become the man he wished to be. He needed cancer. Robbed of that, he was forced to take inventory of his life and all the mistakes he’d made along the way.

~

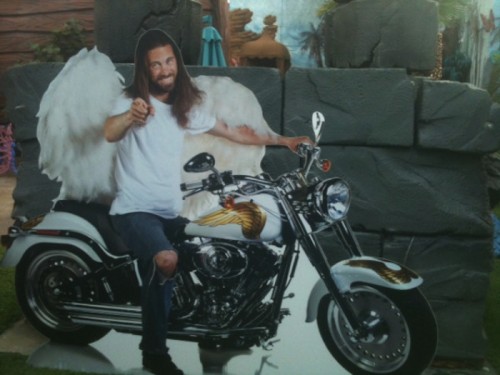

Several weeks before the revelation that he wasn’t dying, my dad went to the Holy Land Experience to “get right with God” before he died. He invited me to go, but being a fiercely anti-religious teenager, I passed. He went with his sister and the two of them shared what he described as a “life-changing experience.” He told me that the Passion—a re-enactment of Jesus’ crucifixion—had moved him to tears. It was clear something within him was stirred.

In the days that followed, I saw a new man entirely. He seemed more patient and magnanimous. He spent his Sundays at church and his afternoons thumbing through a Bible. That lasted until the first of the month, of course, but I don’t doubt its authenticity.

It caused me to reflect. Is there anything capable of moving me to tears? Anything that could compel this ardent cynic to become a better person? Though I had been so righteous and dismissive, I knew I had no Jerusalem, or even a corny, theme-park proxy for it. Though I found it misguided and delusional, I was envious of his faith.

It’s easy to be cynical about a place like the Holy Land Experience. But he wasn’t. The gaudy shawls on the actor who played Jesus didn’t offend him. He didn’t mind that the teen working the concession stand had a faux beard to look like Moses and was charging five dollars for a soda. He wasn’t upset by the obvious dichotomy between Jesus’ message and the cesspool of commercialism in which it was presented.

He was in a place that suggests nothing is sacred and all is beholden to the dollar, yet managed to have an authentic experience of emotional and spiritual gravitas. In Orlando, which could easily be defined as hell, he found something resembling heaven, if only for a little while. That’s a miracle indeed.

This was perfect to read on a Sunday morning

because there’s a mighty sermon here.

Excellent writing, sir.