AN ODD THING just happened to me. I am writing this essay at a desk in a public library, the British library, no less, the largest public building built in the UK in the 20th century. I’m sitting, in silence, in a busy reading room, surrounded by literally hundreds of people. Most of us are tap-tap-tapping away at their computers, each in our own world, near enough to hear one another’s breathing and yet entirely isolated in our silence, the contractual silence that is the condition of our being here. Not that this is anything out of the ordinary. The “funny thing” happened outside in the café, where, having eaten alone and also in silence, an unknown man at a facing table called me over as I was leaving and asked, in flagrant contravention of unspoken library protocol, what I was working on. He invited me to sit, which I did, and we proceeded to chat with the superficial, stilted brevity of such awkward encounters, until sufficient time had elapsed that I felt able to take my leave without appearing rude. Now installed at the silent haven of my desk, I’m trying to work out what to make of this unexpected, unsolicited encounter. I was uncomfortable, and wary about why this stranger called me over and the demands he might make of me. I was also slightly irritated, unfairly disinterested, from the outset, not wishing to confide or to be confided in, eager to return to myself and my own thoughts. I also had the niggling suspicion that this was some kind of set-up, a trick to make a fool of me or to get something out of me. I was waiting for the punch line to this protracted, unfunny joke; for him to ask for my money, or my number; for his friends to appear and make a scene. Perhaps cynically my first thought was “is he for real?”

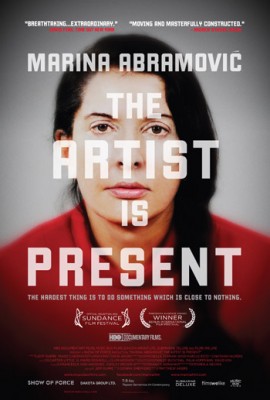

And, all those feelings – they could be ascribed to contemporary performance art. There’s been a huge surge in performance’s popularity the past few years. This summer Tate Modern opened their Tanks as a dedicated space for performance and video installations, while in the museum’s Turbine Hall Tino Seghal staged These associations , the first live art piece to be performed in the towering, empty space. In 2010, his This Progress, spiralled up the central rotunda of the Guggenheim Museum, and there were seventy-seven days of Marina Abramovic’s mute, immobile presence in MoMA’s atrium (The Artist Is Present). Here on this side of the pond, the Hayward Gallery in London staged Move: Choreographing You, while,. this year a whole floor of the Whitney Biennial was given over to performance, and in LA, there’s even a new gallery set up by hip young artists dedicated to, guess, yes, performance.

The Abramovic phenomenon in particular has come to exemplify the complicated alliance between performance, the museum, and institutional and commercial gallery spaces. For all its professed immediacy and the emphasis on the ephemeral “present,” MoMA did a good job of packaging up “the moment” and circulating it. There are photographs, official catalogue and the feature-length film. And, then there were the follow up shows later that year across both of Lisson Gallery’s London spaces exhibiting documentation from earlier Abramovic performances. All of which seems to scream, precisely, that the artist is not present. However you choose to evaluate the work and despite any reservations you may have about the mythical status of the artist or the art institution as a sanctified space, what’s undeniable is The Artist Is Present celebrated the face-to-face one-on-one encounter. And, that exchange is at the heart of the performance revival.

The week the Tanks opened, the Tate’s chairman Nicholas Serota talked in the Independent about how the space responded to people’s desire “to have an experience of the art of ‘with’… to be with something.” He went on to explain: “That kind of new form of interconnectivity is what performance is providing. We are a little bit fed up with people and organizations doing things at us. Maybe that’s why we are looking for something.” The emphasis is all on the ‘with.’ The idea is performance goes a step beyond merely asking us to be engaged spectators, instead it offers the possibility of response, of interaction – of connection. It’s me facing you and something passing between us, something experienced directly and even sometimes violently. Something real. But why are we looking for these things now? And why do we think that performance can deliver them?

It would be easy to point the finger at the rise of the internet and Facebook and the like. Also in our globalized era you can blame multinational capitalism, with its emphasis on individualism, and the abstract ease with which capital flows over borders while production and consumption become increasingly isolated. Thanks to communications and transportation the world and its markets are always “on.” We’re up-rooted and hyper-connected. The implicit corollary? Community is virtual, real neighbors disappearing. This fear underpins British Prime Minister David Cameron’s “big society” rhetoric. His suspicion is shared by big and little ‘c’ conservatives, and many others too – possibly even the world of performance art. And, now when we spend so much time looking at monitors, the idea of looking into someone’s eyes, is rare – even maybe fetishized. In fact, so many people cried while sitting opposite Marina Abramovic during The Artist Is Present that a whole tumblr was dedicated to them. (It’s interesting, though, that to provoke such a charge, Abramovic had to become less like a human and more like a piece of art: silent, passive, immobile, registering no emotion at all.) The potential “with” that performance can offer, and indeed sometimes promises is for “real” contact with other people.

But this is tricky territory. Firstly, the very idea that performance is “authentic” or “real” seems perverse or, at least, somewhat counter-intuitive. “Performance art” is called that to distinguish it from “life” and to mark it out as a stylized, hyper-codified way of acting and interacting. Even though, “real life” itself can be reduced to a series of daily rituals and performances, most people are keen to distinguish (perhaps erroneously) the roles they play from the people that they are. The promise of the unique and personal “connection” or “exchange” offered by performance is therefore conflicted or contradictory, since it relies on a repeatable and rehearsed formula. This was my issue with These associations, Seghal’s piece at the Tate (described so well recently in The Weeklings by Miranda Pope). Rather than experiencing the enriching, emotional exchanges I’d read about in countless reviews, both times I went, I felt isolated. I was alienated from both the private logic of the group and everyone watching from above or the side. All the time a little voice in the back of my mind was asking the performers (“interpreters,” in Seghal-speak), “How many times have you told this story?” and “Does it matter what I say in response?” The exchange’s brevity and anonymity was inhibiting (and intimidating) rather than liberating. I’m sure I would have felt the same sitting opposite Abramovic, with those big, dark eyes boring into me, surrounded by curious onlookers and impatient queuers. In fact, I can imagine few things more disengaging than being herded along at a security guard’s instruction in an interminable, shuffling line ready to take my place, framed in a perfectly symmetrical composition in the middle of MoMA’s glaringly bright atrium. This is always the contradiction with any participatory performance, particularly those like These associations or The Artist Is Present. I can only be a part of the audience by becoming an actor. So, if there are just the two of us, who is spectator and who is spectacle? Who is performing what for whom?

Maybe my experience of These associations wasn’t representative. Maybe I’m being unfair and happened to catch those particular performers on off days. Or, more likely, my lack of engagement was the result of my own social ineptitude. But banal exchanges and stiffness aren’t bad. I don’t mean this as a criticism of the work. In fact, that’s what made it most interesting. By highlighting the day-to-day awkwardness of human interactions, These associations expresses the awkwardness human interactions. An exchange with a “real” person, in whatever situation, can be a redemptive or enlightening – but just like my coffee-shop exchange, it’s equally likely to be uncomfortable, humdrum and frustrating.

If performances like These associations or The Artist Is Present can be called intimate, it is because they’re also seductions. The promise of a union always held at a distance. The very title of These associations implies something that isn’t fixed but a slippery hop, skip and jump across things and between them, coming together and moving apart, flighty and never fixed. One’s associate. Not friend; not lover. It has the slightly cold, slightly negative edge that manages to convey very precisely the ambivalence I experienced during the piece. Which, in reality, is probably exactly to be expected. Because that’s how relationships are and that’s how communities are. Complex and conflicting; hesitant and unpredictable, and this is true as much for the embodied and the local as for the far-flung and virtual.

Fetishizing, as Serota seems to do, the “with” of performance as the restoration of a broken social bond also seems to diminish performance’s potential to be willfully oppositional or “against.” Since the early 1960s, when they began to be known as such, performance artists have used direct engagement with their audience to be confrontational, flying in the face of the art world and its institutions, but also of social conventions and expected ways of interacting. Take the Viennese Actionists pissing in the street (Otto Muhl, Piss Action, 1968) and Valie Exports’s Tap and Touch Cinema, where members of the public were invited to touch the artists naked torso through the curtain of a ‘theatre’ box covering her upper body, through to Chris Burden asking a friend to shoot him in the arm from a range of fifteen feet (Shoot, 1971); Vito Acconci masturbating under a wooden ramp as visitors walked above (Seedbed, 1972); Gina Pane carving makeup into her face and bleeding as she watches herself in the mirror (Psyche, 1974); or Abramovic herself, standing naked in the small front room of a gallery in former Yugoslavia, next to a table of objects offered to the audience to use on her as they pleased (Rhythm 0, 1974). The history of live art is littered with famously transgressive, intrusive and violent works. These performances also made the spectator complicit in them, taking the form of accusations, rather than dialogue. What does it say about you to watch a man be shot, even if it is at his own instruction, and not stop it? Does it imply a perverse pleasure in the pain of others? A cold, clinical disinterestedness? An abuse of responsibility? What is an appropriate response to total passivity? What’s being offered? Who has the power?

It’s no coincidence that most of these famous pieces took place in the 60s and 70s, a time of intense social upheaval: the civil rights movement, gay rights, feminism, Vietnam protests, student protests across Europe…. All of them questioned the established the social order, and all of them staged massive public performances on a grand scale (and, what is a demonstration, if not a performance?). Voila: oppositional collectivity.

So, why now, at another moment of political and social unrest? Why are so many big institutions, opening their doors to performance, and why are they all so nostalgic? Not only are they reviving old performances, but also in this appeal to a redemptive “with,” they seem to be trying to restore a notion of community that’s seen to be under threat at the moment.

Take the most recent example: Martha Rosler’s ”performance,” her Meta-Monumental Garage Sale at MoMA. (In the same atrium that hosted Marina Abramovic two years ago). A literal garage sale, it’s the last in a series that she’s hosted in galleries since 1973. From her early video works such as Semiotics of the Kitchen (1974-75) through to her photomontages in which images from the war in Iraq collide with domestic interiors (Bringing the War Home: House Beautiful 2004, itself a reprieve of an early series from 1976-72 about the Vietnam War), Rosler’s work has sought to politicize the domestic, or domesticate the political. Holding a tag sale in a space more accustomed to displaying works whose value is so abstract and far removed from day-to-day financial transactions as to be almost meaningless makes a timely statement about the fickle nature of value. It’s all made more poignant by recent events in New York. But there’s something undeniably kitsch about this piece in an era of Ebay and Amazon marketplace. What’s most interesting about the haggling and bartering here is the idea that an item’s price has a narrative dimension, which allows its personal and affective value to be taken into account. But price, ultimately comes down to the same thing –the mechanics of desire, which determine how much someone is willing to pay.

I also bristled at MoMA curator Sabine Breitwieser’s description of the show in the New York Times as “a collective action.” Post-Sandy, there are probably numerous other projects in communities across the city far more worthy of the term. Meta-Monumental Garage Sale, for all its digs at abstract economics, involves a basic financial transaction: a $25 ticket fee for the chance to meet a famous artist. It’s funny how, after two decades of attempts by participatory and socially engaged practices to knock down the ivory tower, this strand of performance is almost idolatrous, with the authentic exchange promised by the performative “with” relying on the Artist, either directly (Abramovic) or indirectly (Seghal), for validation.

A review in the New Statesman uses the word ”hagiographical” to describe the film of The Artist is Present released earlier this year, a sentiment I’ve heard echoed elsewhere. I haven’t seen the film myself. I’m not sure what it could add to my (non) experience of the piece other than adding to this process by which Abramovic is gradually crystallizing into legend, which sits uneasily with my understanding of what her practice has always been about. But, I do know the movie has been wildy popular, both here in the UK and in the States, where it was first shown on HBO and is now on Netflix. Which is interesting, when you think about it, since on-demand television implies a kind of interconnectivity that’s about as far as you can get from the kind in her original performance. Yet, there’s a sense in which the film itself constitutes a kind of shared performance, even when viewed from the comfort of one’s own armchair. It performs in a different way, but it still offers the potential for emotional engagement, and it also becomes a shared reference point for conversation and communication.

Safely back in my quiet library seat, I’m surrounded by a pile of catalogues and performance documentation – and I’m wondering if I was too abrupt with the guy in the coffee shop. Did I leave too quickly? Should I have let my guard down a little and taken as a gift this unasked-for moment with someone who seemed genuinely interested in me and my work. Exchanges like this don’t happen all that often. But, here’s what it comes down to: as much as we may sometimes yearn for “real” connections with “real” people, just as often we are happy to experience this “withness” from the comfortable distance of our own space. Not everybody who was moved by the Abramovic movie would have been into the performance and vice-versa. What our hyper-connected age gives us is the possibility of interacting on a number of planes, none of which need necessarily be prioritized. Then there’s not interacting at all because sometimes, as Marina herself would doubtless confirm, you need the time and the space to be left alone with your thoughts. And, I’m sure that is as true now as it ever has been.

http://vimeo.com/40835539

<3 ice cream

Pingback: Praxis Makes Perfect | High Time: On Ritual and Duration | Art21 Blog

Pingback: Is He For Real? The Blurry Boundaries Of Contemporary Performance | Time-Based Studio

Pingback: Praxis Makes Perfect | High Time: On Ritual and Duration | Uber Patrol - The Definitive Cool Guide