DURING THE ELECTION SEASON, I spent some time on a writing project that involved dictators of the twentieth century. As I researched and then wrote about Pinochet and Kim Il Sung, Gadhafi and Saddam, Stalin and Hitler, the same phrases kept popping up: tortured…imprisoned without trial…ordered the execution of…crushed all who disagreed with him. Since 9/11, these phrases have taken on an uncomfortable relevance to the United States.

“We do not torture,” George W. Bush famously assured us—but we do. His own Attorney General, the just-following-orders Alberto Gonzalez, provided the legal framework for doing so, in the process putting the very definition of torture on the rack.

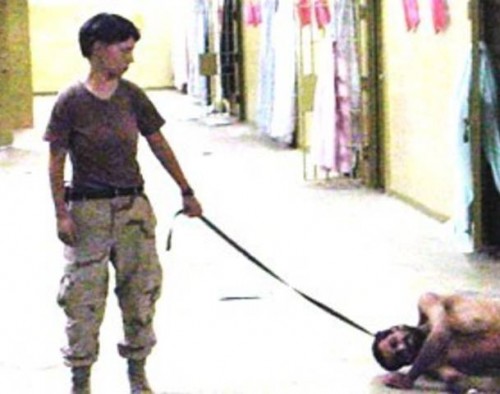

We torture, and our leaders defend the torture, and we make Oscar-nominated films extolling the torture. The torture does not really bother us. Abu Ghraib was not as big a scandal as it should have been because, as I’m hardly the first to suggest, the image of (presumed) terrorists being abused did not evoke much sympathy in most of us. So Lynndie England had some fun with some scumbag jihadists. So what. Fuck them.

But torture was—is—just the beginning. We also imprison suspected terrorists indefinitely, without trial. Bush fils started this, rounding up a motley collection of jihadists real and imagined and herding them into the Guantanamo Bay Detention Center. Barack Obama, after promising to close that prison complex—call it what it is: a concentration camp—decided instead to leave it open, thus condemning its inmates to life imprisonment.

So yes, we torture, and we hold without trial. We also blow terrorists (or what we hope are terrorists) out of the sky, like Zeus hurling a thunderbolt. What most liberals do not like to admit is that when it comes to random execution from on high, President Obama, the winner of the Nobel Peace Prize, is more guilty than even Bush/Cheney.

~

That the United States, the alleged Home of the Free, should flex some authoritarian muscle will not be a surprise to anyone versed in modern history. Our government spent much of the last century cozying up to dictators. An uncomfortable number of the despots I researched were, at one time or another, friends of the United States. Stalin was our ally in World War II; same with Chiang Kai-Shek. Tito was on our payroll for the duration of his reign in Yugoslavia—this was how he managed to keep his country, alone among the Communist states of Eastern Europe, out of poverty. We fomented coups in Iran and Chile, replacing the democratically-elected socialists Mohammad Mosaddegh and Salvador Allende with the reinstated Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi and the Kissingerian lapdog Augusto Pinochet, respectively. We supported the Taliban before we decided not to; we were bosom chums of Mubarak until the bitter end—Hillary Clinton and Mubarak’s wife were close—and we continue genuflecting before the autocratic House of Saud (home to our “secret” drone-strike base). However small-r republican we may be at home, the truth is that the USA prefers to work with despots abroad. Compared with the slow, measured steps of a democracy, tyranny makes for easier, more expedient governance. It is this predilection for enabling iron-fisted strongmen, and not “our freedoms,” that our enemies hate us for.

But the line has blurred. Our foreign policy, which grants the president powers approaching the dictatorial—and make no mistake: when a single human being can order executions in faraway lands from the Oval Office, without oversight, and they are carried out almost immediately, that is the stuff of dictatorship—has begun to seep into our domestic affairs.

All of the dictators I researched made a habit of imprisoning people without trial, often for political reasons. Hitler had Auschwitz and Dachau, and Stalin his gulags, just as Tito sent dissidents to the dreaded Goli Otok prison camp. Pinochet’s hold on power demanded he imprison—or, more often, “disappear”—his rivals. Kim Il Sung would intern those he did not approve of for generations, making sure their progeny remained incarcerated, too. Although we in the U.S. have deviated from our Constitutionally-mandated right to trial by jury from time to time during our history—Lincoln jailed journalists and suspended habeas corpus, FDR built internment camps for Japanese-Americans, and our treatment of both pacifists and “communist sympathizers” has been appalling—the United States has had a better track record than most with respect to fair trials. Yes, the system can be corrupt; yes, the guilty walk free (O.J.!) and the innocent do time. But our commitment to a fair hearing before a jury of peers is something we could always count on.

Could. Past tense.

Despite his 2008 campaign promises and some initial plans to move the “detention center” to Ohio (while maintaining the brazenly un-American policy of indefinite confinement), President Obama, at the urging of Congress, has given up trying to close it. Since it opened 11 years ago, Gitmo has held 779 men. This number includes three teenagers. Most of them have been released, generally to prisons in their home countries. We are told that the remaining 167 prisoners are the worst of the worst. We are told they are not nice men. We are told they will stop at nothing until they take America down. Perhaps. But surely there must be a more humane way to handle these people than indefinite detention in what Amnesty International calls “the gulag of our times”?

The horror of Gitmo might, I suppose, be written off as a historical oddity, a necessary evil to protect us from a new threat to America—FDR’s camps and Honest Abe’s jailed journalists—but for the pesky fact that it was merely the prelude to something more ominous. On New Year’s Eve, 2011, while the nation’s attention was focused elsewhere, President Obama signed into law the National Defense Authorization Act, which makes it clear that not just foreign nationals can be rounded up on faulty pretenses: so too can American citizens who engage in “terrorist” activities. For now, that definition seems to be confined to those who might bring harm upon the nation, killing a lot of people. But the definition is open to interpretation. Prosecutors have suggested that Bradley Manning (who has now been held without trial for over 1000 days) and Julian Assange are terrorists. And the rogue hacktivists from Anonymous. And the dearly-departed Aaron Swartz. Next it might be union leaders, radical environmentalists, porn enthusiasts, pot smokers, writers who defend the right of 9/11 researchers to exist, known anarchists from Twisp, subversive YA novelists. If a middling bureaucrat like Alberto Gonzalez can narrow the definition of torture, it stands to reason that expanding the definition of terrorist will not pose a problem. This, to me, is more terrifying than any terrorist plot.

But it gets worse. The policy of the United States is no longer to capture and detain “terrorists,” but to pick them off via drone strikes. Summary execution, needless to say, is another hallmark of totalitarianism. For many months now, Obama has not publicly acknowledged the drone program—indeed, his former press secretary was expressedly forbidden to mention it at all—although it has long been an open secret in Washington and, one supposes, the Arab world. It is only with the confirmation hearings of John O. Brennan as CIA director that information began to go public. (Brennan, an early adopter of Zero Dark Thirty-style torture as statecraft, is something of a poster boy for the Patriot Act, with all its attendant if inchoate horrors. That his hearing was suspended when protesters would not go quietly briefly restored my faith in humanity.) The president’s rationale for ordering the strikes, one imagines, must go like this: given the premise that a) a vengeful Islamic extremist is not going to stop trying to attack the United States while he still breathes, much like the villain from a bad horror movie, and therefore must be eliminated, and that b) drone strikes kill less indiscriminately than “smart” bombs, to say nothing of troops on the ground, it is therefore prudent to order drone strikes. I’m not naïve enough to suppose that any world leader can govern without making decisions about life and death. The president is managing risk here, playing with probabilities, applying the Bayes Theorem with regard to drone strikes in a way that would make Nate Silver proud. In short, he is executing his primary job, which is to defend the citizens of the United States. I like to think that if I knew what Obama knows, I would make the same decisions. Indeed, Brennan himself said as much during the hearings, explaining that “such actions [are] as a last resort to save lives, when there’s no other alternative,” and that the American people don’t grasp “the agony that we go through to make sure that we do not have any collateral injuries or deaths,” and that he feels “the American people will be quite pleased to know we’ve been quite judicious” in deciding when to hurl the Jovian thunderbolt at an alleged evildoer. Last week, Senator Lindsey Graham, a member of the Armed Services Committee, put the death toll at 4,700—almost 2,000 more than the death toll for 9/11. Are there really 4,700 high-level al Qaeda operatives in the world? Or, put another way: why have we killed so many people?

We’ve already used drone strikes to kill a U.S. citizen in Yemen; when will we begin using them on U.S. citizens at home? Glenn Greenwald, whose regular column in The Guardian is a must-read for anyone interested in our slow descent into totalitarianism, recently proposed that Christopher Dorner, the rogue LA cop-cum-domestic terrorist, represented a sort of case study in whether this policy should be used here. Dorner retreated to a cabin near Big Bear Lake, California, where he and pursuing officers had a stand off; several officers were injured, and one died. Because a drone strike on that remote cabin would have saved lives, the Dorner case could be, and probably will be, used at some point to defend the use of drone strikes domestically.

I have given the drone program considerable thought, especially while researching the dictators, and I have determined that what concerns me are not the strikes themselves, excessive as they seem, as much as the complete lack of oversight. Similarly, I have no issue with “the worst of the worst” rotting in prison, but I do object to the lack of due process. If a terrorist can be blown to smithereens at the whim of a single individual, then so can I, and so can you. If a terrorist can be held indefinitely without trial, then so can I, and so can you. Remember: what allowed Hitler and Stalin, Saddam and Gadhafi, Genghis Khan and Attila the Hun, and every other absolute ruler throughout history to torture and imprison and kill on a whim is the fact that they could.

Today, the man with his finger on the button is the genial Barack Obama, a man I voted for, a man I like and admire, a man whose judgment I trust. The president strikes me as grounded, guarded, pragmatic, and smart. Whatever some may believe, Obama is not Hitler. But the next guy might be. And therein lies the terror. Not recognizing this clear and present danger is Obama’s greatest failing as president.

Hmmm…how’s this for a beginning pushback?

“If a terrorist can be blown to smithereens at the whim of a single individual, then so can I, and so can you. ”

You’re right, literally, as “You and I” can be blown up by a terrorist.

You’re wrong in the implication that the US government will ever do it to “Greg Olear or Caleb Powell.” Unless, of course “You or I” decide to become terrorists or decide to go overseas and hang out with terrorists.

I fear the terrorist. I fear the Chris Dorner-like psycho in our society, I generally don’t fear the US government or police force, although I think specific elements are worthy of mistrust and worse. Don’t get me wrong, US foreign policy defines “moral ambiguity,” and characters like Kissinger and Cheney seem to have sociopathic concerns for the women and children of our enemies. But you, Greg Olear, have nothing tangible to fear from the US government and you never will…and you should know it.

Prejudice is a form of exception-rule dyslexia, the prejudice that we have toward the military or police is as excessive as our worst racial prejudices, and no less valid.

Obama made the world safer by destroying Anwar al-Alwlaki.

Deborah Baker’s National Book Award finalist The Convert, and Deborah Scroggins’ Wanted Women about Ayaan Hirsi Ali and Aiffia Saddiqui, and Ian Buruma’s Murder in Amsterdam are the tip of the iceberg when it comes to Islamic fundamentalism, but good places to start.

I’m part Iranian (despite my loaded Christian name), lived in Abu Dhabi, and I will stand up for a lot of Muslims, but al-Awlaki…never.

I’m not arguing that al-Alwlaki didn’t deserve what he got. I would have cheered if a drone missile blew Dorner off the face of the earth, just as I was happy that the hideous man in Alabama who held that child hostage was killed by the FBI.

The point is, when we strip away our ability to have trials, and grant our government the ability to kill people it deems “terrorists” — and do so in a way that doesn’t allow for judicial review, as the Supreme Court ruled today — it’s a slippery fucking slope. I think you’re probably right, that you and I have nothing to fear from the government…but I feel much less secure in that belief than I did on Labor Day, 2001.

Thanks for the book recs, and also, as always, for your take on things.

Gotcha, there’s a reason for due process, but in the three examples you mention, what other options would there be? In each case you don’t have enough info or time, even with al-Awlaki, a different case because of being overseas and on the hit list for years but who would have been difficult to capture alive.

It’s important to voice concerns and remind politicians to not overstep bounds.

Covert ops have been around for years, not that I’m an expert as by their very nature many remain off radar, but the battle’s migrated from communism to fundamentalism.

To steal from Thomas Paine, government is either a necessary evil or an intolerable evil. Ours is necessary and that of the fundamentalists would be intolerable.

Living in China, I’m often surrounded by expats bitching about why China sucks, and of course there are news reports and blogs and tweets about why it’s the most evil country around – basically, a bigger version of North Korea.

What I observe most commonly is that Americans complaining about China are often complaining about stuff that goes on at home – indefinite detention, corruption, govt spying on the people, etc. And usually – admittedly just to fuck with them – I’ll go on a counter rant about how China, which has a fairly indefensible govt, cannot compete with the US in terms of Evil Empire potential. Pretty much the first line of attack is to bring in the word “drone”. Then just list places that the US has gone without any real legal or ethic right, while China – the world’s bad guy – tends to rely on (admittedly childish) words.

Anyway, it’s an argument that works equally well against the left and right.

Nice to hear from you, David!

If we tilt any further toward totalitarianism, who knows, your next teaching gig might be in New York…

I’ll flip a coin. Heads = Pyongyang; tails = NYC.

Pingback: Bush in Rehab — The Good Men Project

Pingback: PRISM: Privacy Revoked in Security Measure — The Good Men Project