ABOUT FIFTY PAGES INTO my recently published debut novel, Perfectly Broken, the parents of a two-year-old have sex. It’s the first of four sex scenes in the 270-page book. A little backstory: in the scene, this couple has fitfully navigated a rough day, the kid is asleep in another room, and it’s summer in New York City. My protagonist, an insecure dad, narrates. He’s horny. What provoked his ardor? He made some good decisions that day, and he was helpful in a crisis. For fleeting moments, he entertains the notion that he may very well be exactly where he is meant to be; all that has come before – even some horrific trauma, some humiliating failure –is OK, because of this day. These factors are like Spanish fly to his libido.

It would spoil the book to go into other scenes, but suffice to say, they’re cut from similar cloth.

While the concept of unattached, animal sex appeals to the id, in writing Perfectly Broken, I wanted to render more relatable – dare I say realistic – sex, while keeping it id-friendly. The canoodling, be it awkward, rushed, interrupted, spiked with guilt or rage, or blunted/enhanced by pharmaceuticals, should still be steamy.

I believe part of the writer’s job is to brighten shadowy corners, elicit feelings of kinship, to make a reader say, “I didn’t know someone else felt that. I feel less alone.” That distinctive intimacy is one of many satisfactions for both reader and author. In creating the sexual aspects of my novel, I hoped readers would recall desire rising at odd times: the spark of a lover’s will, a childhood memory of being safe and cared for, a spate of uncharacteristically risky behavior; a tattoo faded, an appendectomy scar; doing the dishes, guilt, revenge. Stretch marks. Feeling like you know what the fuck you’re doing. Surviving emotional disaster, coming out of a haze to find the landscape broader than before.

And what of grief as reset button? In the wake of devastating loss, a chasm opens within, and the body craves nothing more than physical contact to temporarily fill that space. Words? No. Prayers? No. Sex? Yes, please. Of course grief can shut a person down completely, but it can also demand intimacy, even risky intimacy. It can blunt reason as much as any intoxicant.

These outlier aphrodisiacs are less-trod terrain, at least in my reading. Perhaps not as appealing to the reptile brain as, say, porn, but nevertheless fascinating. Thus, in keeping with the “write a book you’d want to read” dictum, I inserted them, and others, into Perfectly Broken.

Writing Perfectly Broken took about three and a half years. Those forty months or so were rife with emotion, in both imaginary situations created in the narrative, and in worry over how readers (if I found any) would receive some very adult situations. Like, for instance, “the sex stuff.” I would love to say I didn’t care, and in fact, on very good days, that was true. But on occasion, anxiety clouded my mind.

I’d never written an adult novel – I’ve written two unpublished kids’ books, a lot of arts features, and countless songs, some of which have helped pay the bills. I am a family man, the father of an 18-year-old son, and his mother and I have been married for almost twenty-eight years. We’re all active members of a close-knit, rural community of country folk and New York City expats, nestled in the Catskill Mountains.

Crucially, many of these people first encountered me, and still primarily view me, as children’s entertainer Uncle Rock.

Uncle Rock is a persona I created in 2005. He appeals mostly to kids aged 8 and under. Parents appreciate me, too, and in the late ‘aughts, they bought thousands of my CDs and drove their children to my shows, which stretched along the eastern seaboard and even to Texas and California. After many years in rock n’ roll bands, I was striving to be an update on Pete Seeger, to create interactive, edgy music that families enjoyed together. For about six years, Uncle Rock was the primary focus of my creative energy, and I made a living wage. My tagline, courtesy of the LA Times, was “the Ramones meets Shel Silverstein.” I had a lot of fun, especially when my son was part of the band. (He retired around age twelve.)

Generally, I enjoyed audience perceptions of me. I feel sure my fans’ parents did not suspect I was writing a very adult novel while my music spun in their CD changer alongside Raffi and the Wiggles. I almost never talked about my book-in-progress to anyone, fans, friends, or family.

Would these parents, to whom I am grateful, see my book as smut memoir, or just smut, and picture my family, peers, and me in the throes of infidelity, drug abuse, irresponsibility, resentment, deception, and questionable parenting? And if so, wouldn’t that diminish me in their eyes?

I talked to my family about my concerns. To my eternal gratitude, they both said, “We’re fine. We don’t care what people think. Keep going.”

Also, it occurred to me the imagined scandalized parents would need to read my book to make assumptions. And that would probably mean they’d bought it. Which would be good, of course.

Still, if I was going to turn in a completed manuscript, I couldn’t think about them. So I imagined and fixated on an intimate, a person who would bail me out of jail if and when I couldn’t keep my façade intact, when I did what my darkest self told me, consequences be damned. I wrote for the one who really knows me, and would forgive me. Once I hewed to a clear picture of whom I was writing for, the book came easier, and got better, and I finished it.

Nevertheless, while working, I’d not only hear, I’d viscerally feel a voice saying: “Writing this will ruin you. You’re putting close relationships on the line. You cannot afford that. You’re writing explicit sex scenes featuring flawed strivers on the verge of middle age, you’re creating detailed portraits of damaged, often difficult people. Worse, readers will think this is you and your dearest ones, no matter what you say. You don’t know what you’re doing. All this time and effort and risk: wasted. If you get published, you will lose love.”

That voice. Most of us endure a version of that voice. It speaks for the part of me craving the illusion of control over what others think of me. Thankfully, turns out the act of sitting down and writing, of powering through, is anathema to that voice.

As in crisis, the writing process is a getting-to-know-you experience. This can be frightening, but also emboldening. In constructing Perfectly Broken, some unearthed traits proved pleasantly noisy; I discovered aspects that hum and churn and crackle: inside me a punk rock band, a playground, a summer storm, an exultant protest march, an oiled printing press run amok in a basement. The aforementioned warning voice could not compete with all that activity, and faded in the din of production.

I recall reading a scientific article about the effects of worry. It cited data in which worry over outcome is often more physically and emotionally damaging than the actual outcome.

Perfectly Broken has been available for a month now, and thus far, I have not burst into flame or suffered any ill effects I know of. No shunning. I’m happy people are buying it, reading it, and liking it. Some love it. A few do not like it, and that’s OK. The fans mention relating to the characters’ foibles and passions; they enjoy being transported, even if the journey is, at times, perilous, emotionally and otherwise. These readers feel pleasantly, privately recognized. Quite a few are moms. Only a handful directly mention the sex, but those are compliments, too.

Of course people out in the big wide world know naught of me, or of Uncle Rock (he’s not that famous), and among them, there is no discussion of whether or not Perfectly Broken is roman a clef or complete fiction. These people just know if they do or don’t like it. For them, and for my circle, Perfectly Broken is a world we create together, in which their perceptions don’t always align with my intentions. But that is the beauty of story. I conjure the original version, and it gets up-cycled in readers’ minds and memories. They forget or mistake details, and fill them in with their own information. That fascinates me.

Occasionally, I hit the bull’s eye. I get the response I wanted. My reader feels a spark of connection and says, “You nailed it. Thank you. I feel less alone.” I light up with immense gratitude in these moments, when everything I created, whether in fear or inspiration, feels right.

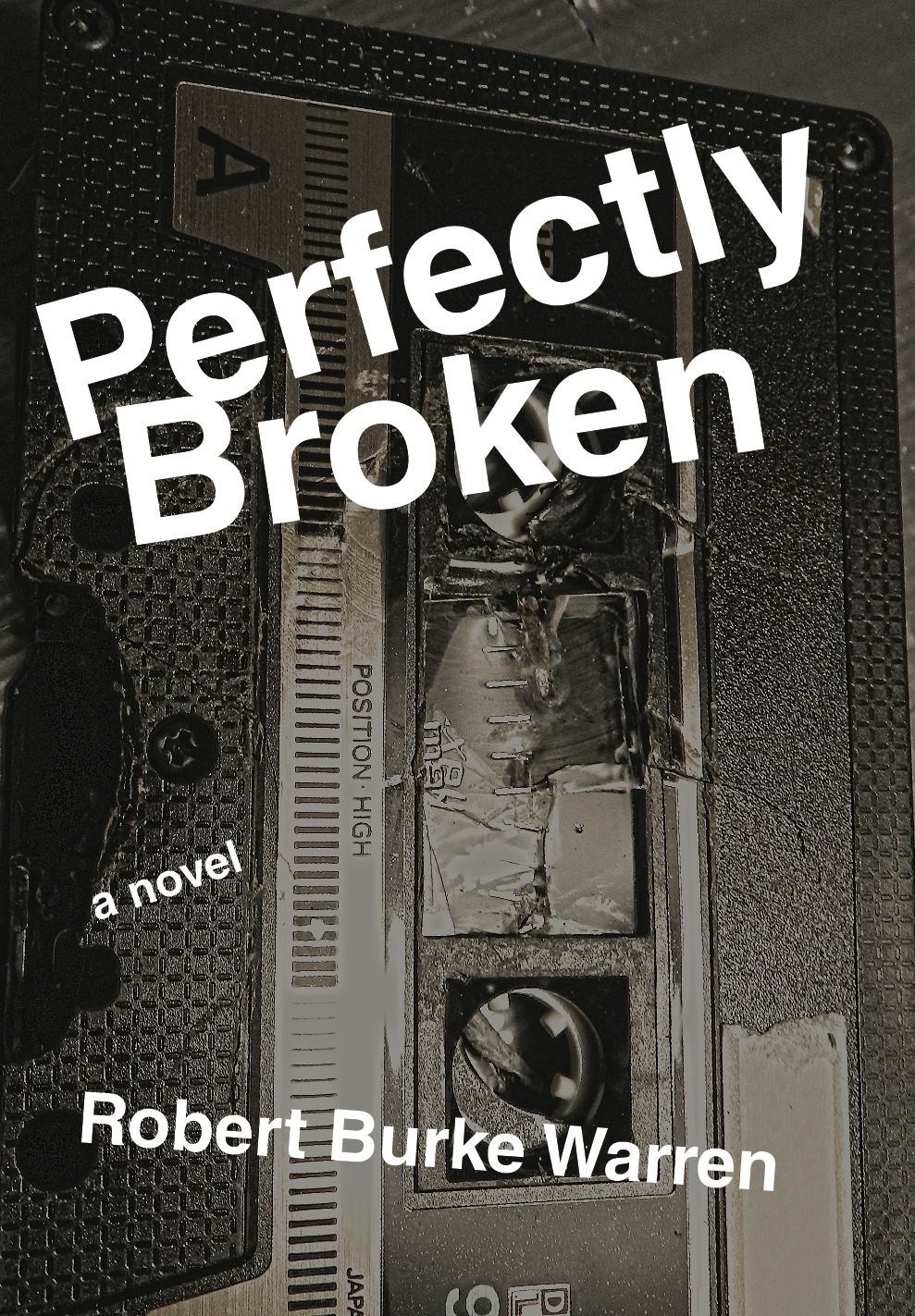

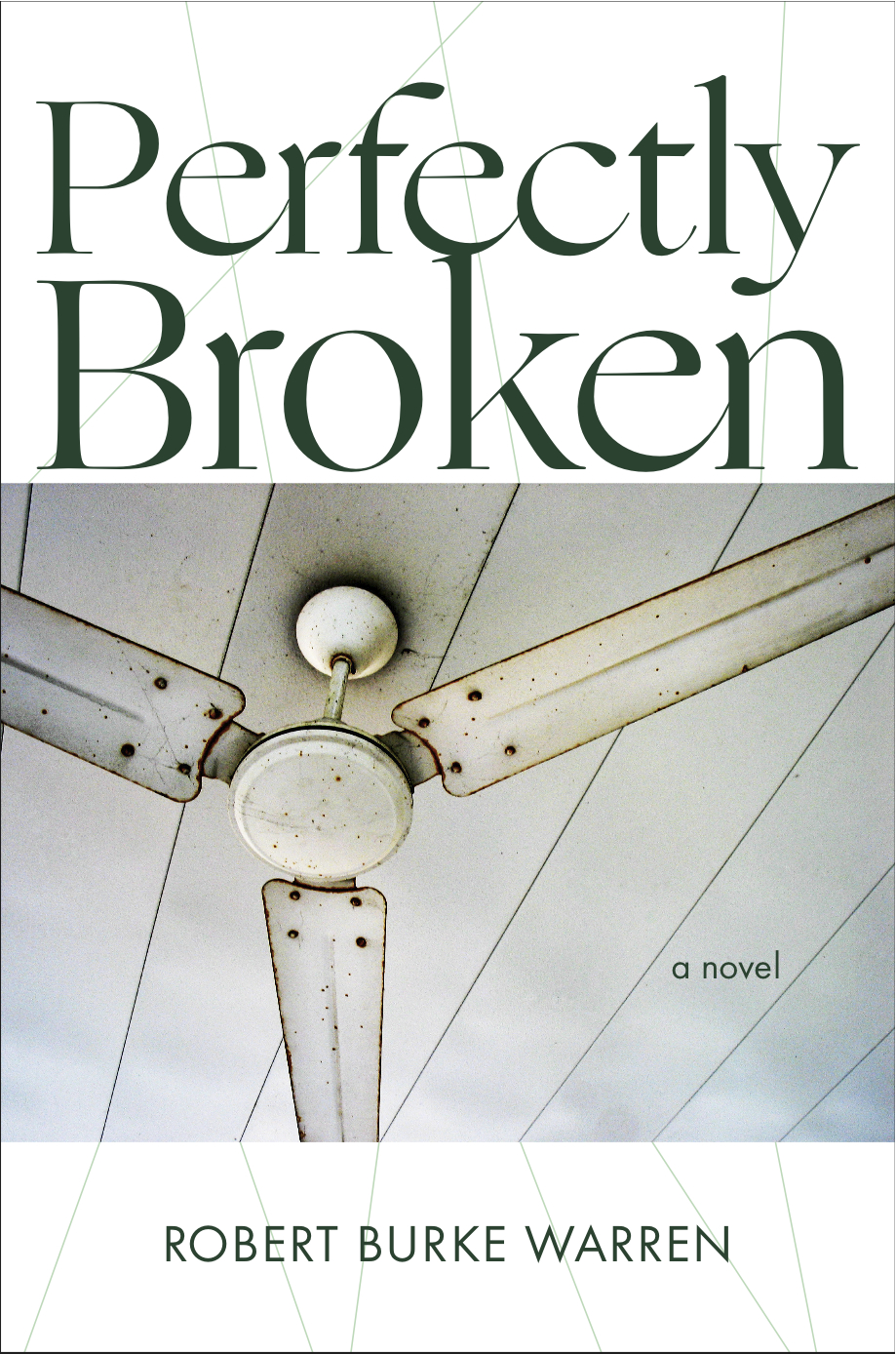

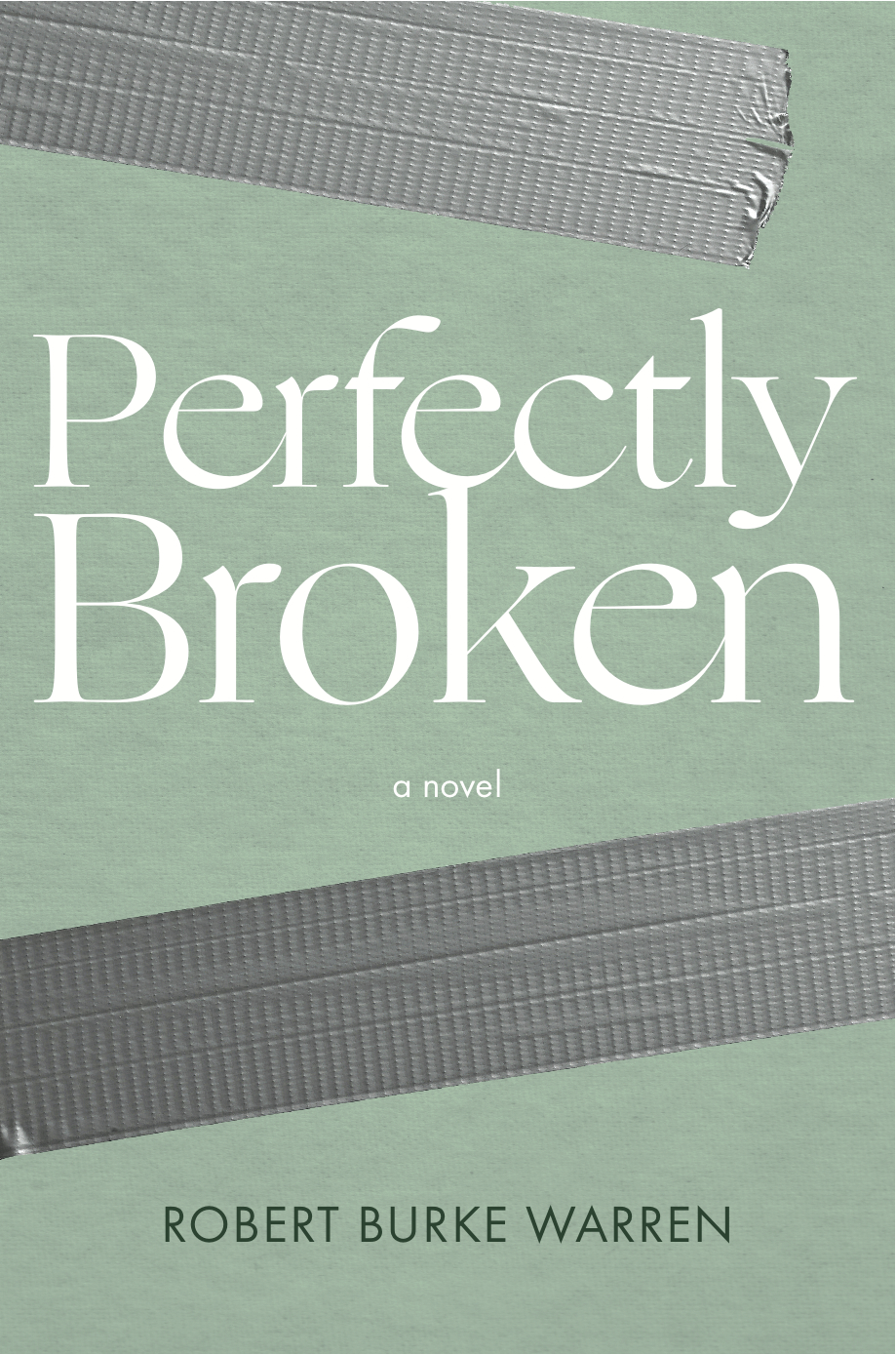

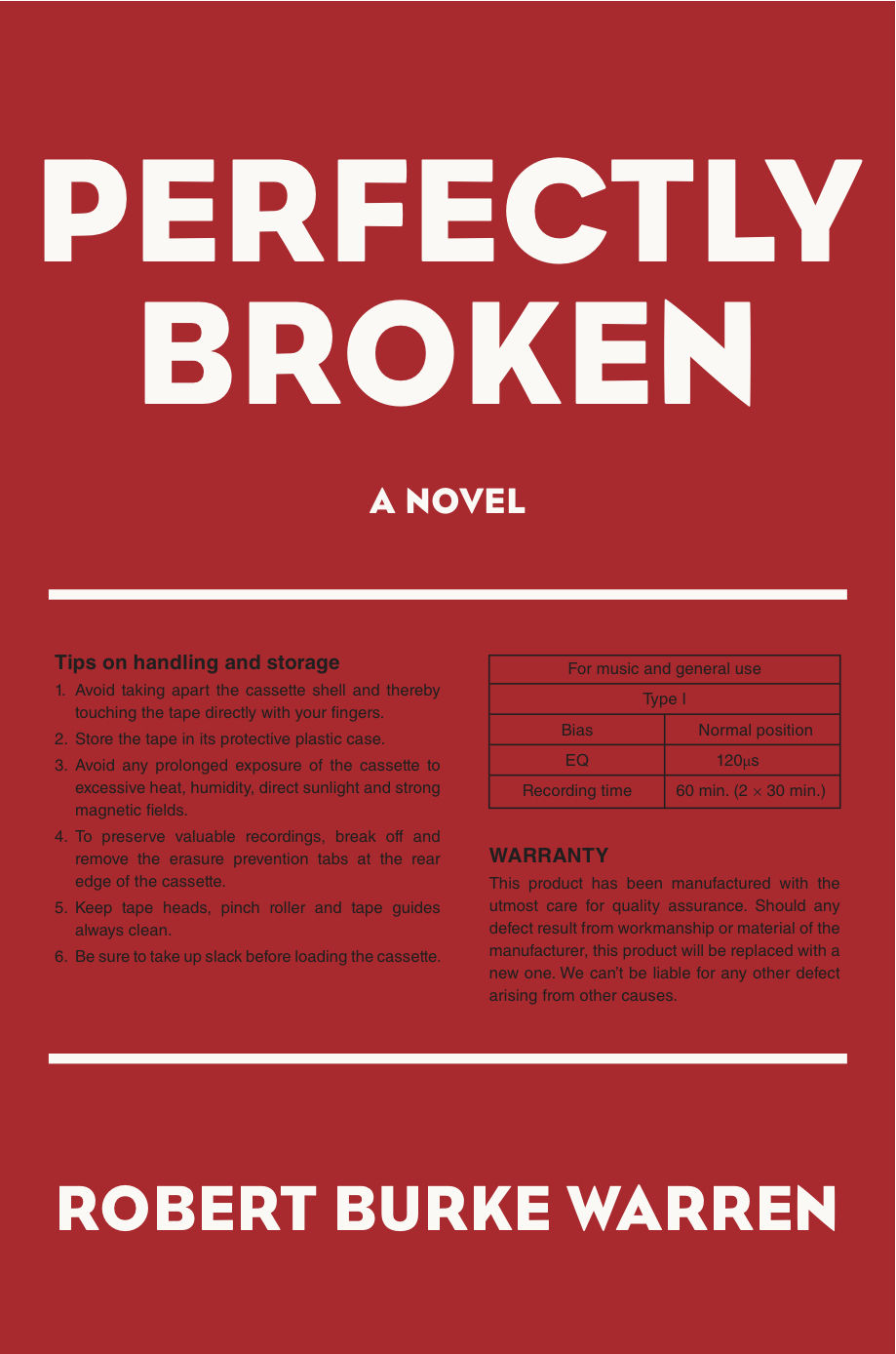

All Perfectly Broken cover designs by Mark Lerner