ONCE A MONTH or so, The Weeklings editors are each required to respond to a single cultural question in this wildly popular parlor game. Music, movies, television, books, dance, sex, sports, art, and death are all up for grabs. There are no correct answers, no political correctness allowed, and only one rule: sheer, brute honesty.

As always, please, no wagering.

What cultural figure of the 60’s best represents you–the way you dress, act, create, see the world, or wish the world saw you. It can be Chuck Berry or Chairman Mao. It can be Betty Friedan or Betty Rubble. More importantly, why?

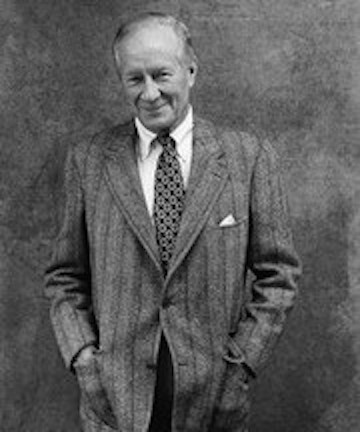

HENRY CHERRY –

It was the 70s by the time I met him. I was six. He had been my old man’s professor and mentor at the University of Virginia. Before that, he ran the art department for Tulane’s Newcomb College in New Orleans, served in the foreign service, and was a Marine lieutenant fighting the good fight in the Pacific Theater during World War II. His name was John Canaday. Just as he tired of academia, Canaday rather extraordinarily landed the best job in the world- chief art critic for the New York Times at the dawn of the 60s. He wrote art criticism for the Times from 1959 until 1973. Canaday virulently derided Abstract Expressionism, a stance that overshadowed his whole career at the Grey Lady. But he wasn’t just an art historian. Canaday wrote spy novels, and a smart restaurant guide for New Yorkers and tourists alike . His most famous work was a single volume treatise tracing art history from the time of David to Picasso that also included a five page architectural addendum in which Canaday thrashed Frank Lloyd Wright’s leaky pretensions. At six, I didn’t know anything about all that. I only knew that when I told him I wanted to be a writer he said, well then, the best practice for that is writing letters to your friends. Then he wrote down his address and handed it to me.

SEAN MURPHY –

I love the ‘60s and write often about the significant things that did happen, did not happen and should have happened during that decade. In terms of import, be it artistic, social, political, cultural, opinions on what matters and endures about the ‘60s says as much or more about the person offering an opinion. In spite of my interest and enthusiasm, I’m pretty sure I wouldn’t have wanted to be a young man in the ‘60s. Sure, I could have been witness to too many milestones to count, in real time. I also could have been killed in Vietnam, or in the streets, or fried my greedy brain with too much LSD or, worst of all, somehow been a Nixon supporter. Every event and individual from this seminal decade has assumed mythic status, but so many of the figures we admire were not admirable people. It’s worth the gifts they left, we say, often correctly. But has there been a single period in American history where so many people get too much credit for talking loud and saying nothing (unlike, say, the cat who wrote that song)? The older I get and the more I learn—about the ‘60s, America, myself—the deeper my awe of the man who changed his name to Muhammad Ali grows. Is there one figure (don’t say John Lennon) who humanizes, epitomizes, the racial, sociological, human upheaval of the era? Here is the rarest of folks who was the best in the world at what he did, at the height of his ability to make history, and money, willing to sacrifice it on principle. And more: a cause that every year is proven more prescient and unassailable on both moral and military levels. April 28, 1967, a little over a month before Sgt. Pepper initiated the Summer of Love, Ali made a statement as brave, audacious and impactful as any of that—or any—decade. Look: we live in a time where we can boast about our beliefs and have our righteousness measured by likes and follows, all from the safety of an overpriced coffee shop. As such, I’ll continue to be humbled and inspired, as a dude with big hopes and modest abilities, by the icon who stared down doubt, ignorance, security and compliance. Ali is the exception to the way we’re ruled, and how we roll, and like the rest of us mortals, his biggest fight took place outside the ring.

JANET STEEN –

I think I have a lot of Franny in me, Franny from J.D. Salinger’s famous novella Franny and Zooey, published in 1961. Franny is a college girl who questions a lot and wants to believe that people are motivated by more than ego. She is slouching toward a vague understanding of what spiritual enlightenment might be. Franny is underwhelmed by her college boyfriend, Lane, who talks too much about himself. She cries in the bathroom, and later, is much more comfortable sitting quietly on the couch with her cat. Quiet study of life and people: I guess that’s what I think of when I think of Franny.

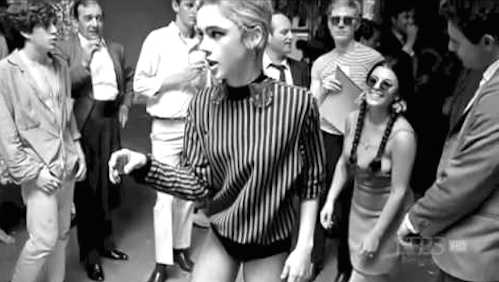

SEAN BEAUDOIN –

I am obviously Edie Sedgewick: pretty, vapid, caught in the middle of a societal and cultural upheaval, from a family of vast wealth, with great legs and a hard jones for rude powders and bathtub gin. I am the avant-garde at its most banal and pretentious, I am a human can of Campbell’s Tomato hanging in a gallery waiting to be bid upon. I am what Bob Dylan left behind and wrote a devastating song about, a pair of lungs that smoked a thousand cigarettes just last week, a neck twisted way past style and grace and mannered aloofness. I am lips to die for. I am sucked Factory-dry. I am a VHS copy of Ciao Manhattan! I am Edie. And she is me.

ROBERT BURKE WARREN –

Among Sixties icons, the Man in Black lingers in my mind. Although he “arrived” in the Fifties, and enacted an unexpected, magnificent final act in the Nineties, Johnny Cash was at his peak and his nadir in the Sixties; his works and actions from this decade resonate most with me. 1963 saw the odd, intense, mariachi-country “Ring of Fire,” his biggest-ever hit, but the mid-60s were a bad time for him – drugs, alcohol, jail, no hits. He surrendered to the shadows and almost didn’t make it back. Yet – by Divine Grace, he insisted – he did make it back, and worked to make things right for himself and his loved ones. He closed out the decade with the still-astonishing live-in-prison albums At Folsom Prison (1968), and At San Quentin (1969), revitalizing his career despite the suits objecting to the LPs’ rawness. He hosted a network TV show (’69-’71) on which he insisted on including the pot references in Kris Kristofferson’s “Sunday Morning Coming Down,” infuriating network execs. As he made strides, he never became complacent; he was always searching, showing that the process is the thing. During this time, he broadened from “country star” to something much, much more, connecting all manner of people to their inner strangers, to their essence, which, it turns out, is not so different from another’s essence. He was country, rock and roll, outsider and mainstream, a spiritual man who also celebrated the fleshy world, honored tradition while also giving it the finger – literally – when necessary. In the Sixties, Johnny Cash found the common ground of rednecks, hippies, Christians, atheists, patriots, apostates, moms in VW Bugs, truckers, and toddlers, to name a few. He wrote “I Walk the Line” in the Fifties, but in the Sixties, he did it. I endeavor to do the same.

ASHLEY PEREZ –

When asked for a cultural icon, my mind immediately wants to ask, “which culture?” So instead of picking an iconic American persona from the 60’s, I choose to look at a subject that is near and dear to my heart: horror. To that end, I would have to select Italian horror master Mario Bava. In 1960, he release, Black Sunday, an amazing gem of a movie featuring Barbara Steele (herself, an amazing cultural icon.) It was his movie, Twitch of the Death Nerve, that was blatantly ripped off to make the Friday the 13th movie. His visual style of directing gives the story atmosphere and inspires terror. Something I am always looking to do as a writer is tweak the little things to enhance the overall story. That is what Bava does through and through. Plus, he brings out the dark side in me. Just look him up and start with Black Sunday and you will be changed. You’re welcome.

LAWRENCE BENNER –

Leonard Nimoy. Sitting in the living room watching Star Trek, while your sister who smells like armpits and tuna fish is drawing pictures of stallions that she fantasizes might someday transport her far away, and while your brother who smells like pot-smoke and semen-crusted socks is scanning old maps and fantasizing about historical conquest, and while your mom is in a distant room, smelling like Tom Collins mixer, reading Agatha Christie and weeping, Spock is pinching people’s necks until they pass out, arching his eyebrows, ordering instant magical food from behind a sliding door, taking it back to his room full of vaguely Buddhist-looking statuary and moody red light bulbs and throwing on a record-tape—that one with the Vulcan Harp music on it—and smoking his bong while brushing on blue eyeshadow.

JAMIE BLAINE

I was a skinny sophomore with prescription sunglasses and a peach fuzz mustache. Secretly crushed on Tiff Taylor for nearly a year before I asked her to Midwinter Ball and she finally said: yes. Desperate to impress, I showed up on her doorstep in a midnight blue tuxedo, hair professionally coiffed from Impressions by Rikki and my uncle’s fake Rolex hanging loosely at my wrist. “If you really want to look sharp,” Unc had suggested, “lose that tie and wear your collar open.”I shoved two sticks of Trident into my mouth, slipped another shirt button loose and rang Tiff’s bell. Her dad answered with a scotch on the rocks in hand, looking like a cross between Colonel Sanders and Ed McMahon. “Sir,” I said, flashing a thousand-watt smile. “How you doin’ tonight?” He looked me over, swaying, confused at first, briefly perturbed, finally indifferent. “Tiffy,” he called towards the top of the stairs, “Sammy Davis Jr. is here.”

GREG OLEAR

The Sixties are a vastly overrated decade, fondly recalled by former hippies who now vote Republican and Gen Xers who worship the over-commercialized likes of Jim Morrison, Jack Kerouac, John Lennon, and similar “cool” figures who rose to prominence at that time. If made to select a cultural icon from this ten-year period, I’ll go with Frank Sinatra. Sure, the best was no longer yet to come, but he was still one of the most famous people on the planet — a singer, actor, lover, fighter, and bon vivant. He recorded “Sinatra at the Sands” in 1965. He was a tireless civil rights advocate, who was integral in desegregation of Nevada casinos, and a big supporter of Martin Luther King, Jr. Also he slept with half the actresses in Hollywood. As a fellow Italian American from New Jersey, I can’t help but admire the doors he opened. I was living in Hoboken, where he was born, when he died, and the place went nuts. EVERYONE paid homage. Even the gangbangers in the low-ride cars with the purple lights underneath were blaring “Luck Be a Lady.” #Respect.

Ah, I love this:

At six, I didn’t know anything about all that. I only knew that when I told him I wanted to be a writer he said, well then, the best practice for that is writing letters to your friends. Then he wrote down his address and handed it to me.

Pingback: Muhammad Ali's Biggest Victory - Murphy's Law

That was wonderful…but, now I’ll be singing Sammy Davis songs all day!

Pingback: Original Poem: ON THIS DAY IN HISTORY, 1967: MUHAMMAD ALI REFUSES ARMY INDUCTION* | Murphy's Law