WHEN I WAS 14, I became a musician to get two things: revenge and girls. I did not seek to shape swirling emotions, or to express levels of experience so deep that mere language cannot access them. No. In time, I would stumble on aspects of music that make it what philosopher Immanuel Kant called “the quickening art,” i.e. the art by which a listener connects to the soul, but in the beginning, the only quickening I desired was of a carnal nature. And you know what? It worked. Following that initial “mission accomplished” beachhead (enemies chagrined! intimacy achieved!), I spent years playing bass in rock bands, touring the world, and sharing stages with artists like James Brown, Chuck Berry, John Hiatt, NRBQ, The Cult, the Red Hot Chili Peppers, Jonathan Richman, and, I kid you not, Sir Ian McKellen, all before I turned 25. Mine was a full musician’s life, but, to my surprise, not yet fulfilled.

These days, the half-century mark looms, and my most recent musical memories include playing at preschools and children’s hospitals. That may read like a depressing joke, and when I’m in the getting-to-know-you phase of a relationship – like now – folks often pity me at this point. And that’s fine. The truth is, in those venues, I’ve experienced my most memorable connections through music.

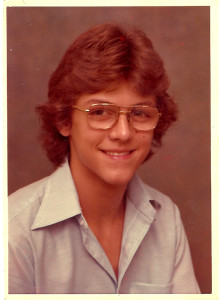

But I’m getting ahead of myself. In 1979, my main musical goal was to elicit cuddling, although I feigned otherwise (“I wanna show how fucked up everything is!”). I was a six-foot-tall, 150-pound 14-year-old with Coke bottle-thick glasses, a lazy eye, and a disco mullet. (Cystic acne would hit me at 16.)

I’d been bullied, abandoned, and beat up, blah blah blah, and wanted to tip the scales. As Nature would have it, during this gawkiest of phases, I was also girl crazy. (Nature’s understandable disdain for humankind is never clearer than during adolescence, when she fires you up while simultaneously saddling you with handicaps both real and imagined.) I needed help. In a rare moment of adolescent clarity, I sensed my newly enlarged hands could make use of the DNA bequeathed to me by my seven-years-deceased dad, who’d been a guitar player and campfire songster.

That DNA hummed in my blood while my best friend, Todd, a fellow misfit with a shock of orangey hair and a weight problem, made the jump to actually playing. Like me, Todd was a bespectacled, card-carrying member of the KISS Army (we’d seen them on the Love Gun tour). He’d been playing a Univox electric guitar for a year, and was getting good at deciphering Led Zeppelin records, which impressed me. My call to action, however, came from seeing Semaphore, a band of rich kids with high-end instruments – a Les Paul guitar, a Fender Precision bass, Marshall amps – and a lead singer who sang way off-key, but in time-honored tradition, owned a PA, and was fearless as a drunk in a karaoke bar. Opening with Chicago’s “25 or 6 to 4,” Semaphore tore up a carport under the palpable gaze of Bonne Bell lip-glossed honeys, and I was sold.

My mom drove me to Atlanta’s Metro Music and purchased a Rythmline (sic) bass, a plywood copy of a Fender like the one Shaun Cassidy pretended to play on The Hardy Boys. She also picked up a small Kustom amp, which I soon manslaughtered. Initially, I took lessons from creepy Mr. Woody, but when he put his porcine hand on my leg and asked, “You like girls?”, I did not go back, but rather hung out more with Todd, who taught me well.

Why bass and not guitar? In part because no other local teen except the kid in Semaphore played bass, and I figured the exotic four-string would draw more attention, preferably from geared-up rich kids and the aforementioned lip-glossed honeys. Maybe it was also instinct. I loved the way the bass fit in my hands, the heft against my protruding hipbones and cutoff-clad thigh, the strings’ slight resistance to my curious fingers before giving up a low, rumbling note I could feel – and make others feel – south of the solar plexus. I still love that.

The rich kids disgusted Todd. While I was cruising the rec-room parties, my friend joined Weight Watchers, dropped about 100 pounds, and answered the call of Rocky Horror and punk rock. For a year or so, he and I fell out, as he blasted the Cramps and Siouxsie and the Banshees to my Styx and Kansas, making his guitar howl with an antisocial intensity that suited him. To freak out his tormentors at our high school, he cut the word FEAR into his arm. In many spiral-bound notebooks, he drew Wes Craven-inspired, intricately detailed pictures of his enemies dismembered, bludgeoned, and/or gutted. He joined no bands, which is probably just as well. (He would later get his master’s degree in painting.)

Meanwhile, after the jumpstart Todd gave me, I woodshedded intensely, and joined metal cover bands Voyage and Ickee Phudj (pronounced “Icky Fudge”). We covered Rush, Def Leppard, Led Zeppelin, Judas Priest, Pink Floyd, et al. I also did a stint in Little Dreamer, a quintet featuring a 16-year-old wunderkind girl vocalist, perhaps the best singer I’ve ever backed. Little Dreamer specialized in Heart and Pat Benatar, and yes, I can still play irony-free renditions of “Barracuda” and “Hit Me With Your Best Shot.”

I cannot say if any of these bands were good, but we all sure thought we were badass; we had fans, played paying gigs, and there was no living with us. And, as a direct result of being a neophyte bass player, I lost my virginity at 15 to a gorgeous, green-eyed girl who looked like Melissa Sue Anderson from Little House on the Prairie.

Still, my cardinal trait in those days was restlessness. After a year, I moved to Athens, Ga., to play in arty funk outfit Go Van Go. I stayed for about 12 months, attended UGA briefly, took a room in an antebellum house, worked at Kinko’s, gigged and toured with Go Van Go, and watched from the wings as local heroes R.E.M. lived the dream.

I chased that dream to Manhattan, where, at age 21, I joined the Fleshtones, all New Yawkers ten years my senior who’d been together a decade, and whose lead singer and mastermind, Peter Zaremba, hosted MTV’s The Cutting Edge. Certainly the best live band I ever played in, this quintet enjoyed considerable fame in Europe, and in the “college rock” scene. Best phrase to describe them: “garage rock titans.” They sounded (and still sound) like early Rolling Stones, Kinks, 13th Floor Elevators, and other bands now celebrated on Little Steven’s Underground Garage. They taught me a lot, and took me across the country, and to France, Italy, Spain, Greece, Switzerland, Germany, Hawaii, and Martinique.

I was a Fleshtone for almost two years. I jammed with Peter Buck and The Bangles, and got to entertain many thousands while seeing the world. While I’m not sure about my teen bands, I know, beyond any doubt, that the Fleshtones were a formidable live act. We weren’t “good.” We were great. And there was no living with us.

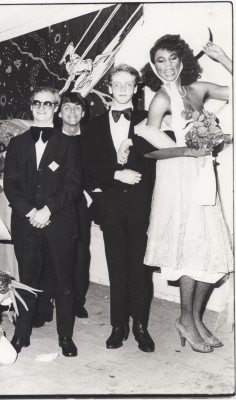

But I was still restless and unsatisfied. I met my wife, Holly, when our bands shared a bill. (Again, early objective achieved.) She played a classic 1959 Fender Jazzmaster, and her guitar hero was noise maven Blixa Bargeld from Einstürzende Neubauten and Nick Cave’s Bad Seeds. Her all-female band, Dar Furlines, pioneered punk polka, and did very well for a while there. They sported corsets, fishnets, sexy boots, big hats, and psycho-beerhall girl attire (think St. Pauli Girl meets Morticia Addams). They offered up raucous proto-riot grrl numbers with titles like “Sworn to Fun, Loyal to None,” “Nichts, Nein, Frankenstein,” and “Polka Palooka.” I was smitten.

Holly was – and remains – a music aficionado with thousands of LPs. Among other things, she introduced me to great songwriters like Paul Westerberg, Nick Drake, Steve Earle, Townes Van Zandt, and even Hank Williams, Sr., who I’d never appreciated. I decided I wanted to be known as a songwriter. I sensed a new chapter beginning in my life, so I quit The Fleshtones, with whom I’d fallen out over several things, and decided to focus on my guitar work and try to be a troubadour. I’d seen a Leonard Cohen documentary while on tour, and it hit me like a bolt. I even dreamed Cohen was my rabbi. In my mind, I enraptured with words and melody, as opposed to volume and showmanship.

Initially, however, this move did not go well. Remember, I’d spent a decade as “the rock bass player.” I soon learned how much harder it is to engage solo, and because I lacked stellar songs and/or a commanding voice, it took years of fitful trial-and-error to get good at it. Meanwhile, Jeff Buckley and Chris Whitley were performing in the bars I played and worked, and they were great, arriving like ball lightning and leaving the air singed in their wakes. (Also, audible gasps from women of all ages.)

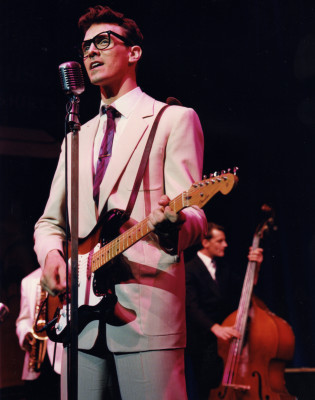

I struggled in the early 90s, pre-Nevermind scene, and accepted bass player gigs while working on songs. I joined and quit several (doomed) acts: a Jane’s Addiction-type band signed to Island, an insane Nina Hagen wannabe German vocalist bankrolled by her PCP-smoking Italian husband, and “the new Billy Idol,” signed to Polygram. While I did get to record at Jimi Hendrix’s Electric Lady Studio, I grew dispirited. My cassette four-track demos and showcases yielded meetings with A & R folks, but no checks were signed. I took more bartending gigs and pursued acting (I’d been a teen actor), enrolling in classes at David Mamet’s Atlantic Theater Company (Bill Macy and Mamet were my teachers). I eventually got some work, most notably as Buddy Holly in the London production of the jukebox musical Buddy: The Buddy Holly Story. As Buddy, I played a Strat, acted, and sang 17 Buddy songs five nights a week for a year, first on tour through the UK, then in the West End. For the first time in my life, I made good money.

The gig started great, but after a year, it was time to come home. I was a mess. I returned to NYC in a depression, and detoxing from Xanax. I turned down an offer to tour as bassist for Garbage, and invested in long-avoided therapy. Holly and I almost split up.

Things began to turn around when, unbeknownst to me, Holly submitted a cassette of my material to Rosanne Cash, who was vetting tapes for a songwriting workshop at the Omega Institute in Rhinebeck, NY. Rosanne accepted me into her Essence of Songwriting class, which changed my life. I would return to this workshop two more times, like a summer camp. I recall looking at my fellow songwriters and thinking, these are my people.

Back in NYC, I bartended, gigged solo, and, for the first time since my teens, learned lots of covers as a means of deciphering songs I liked (and to entertain friends and family). Although now I tackled “My Funny Valentine” and “Wichita Lineman” as opposed to, say, REO Speedwagon’s “Roll With the Changes.” The last time I attended Essence of Songwriting, Holly was pregnant with our son, Jack.

…to this day did great, with raves in Billboard, Mojo, the New York Times, and a spotlight on nationally syndicated NPR show The World Café. When I played live, audiences listened, and I savored that sweet, fleeting sense of my work hitting its intended mark (at least half the time).

Sweet, yes. But being a dad trumps that. Rather than go on the road to promote …to this day, I stayed home on St. Mark’s Place with Jack. Holly, who’d long since left her band behind to write and edit, worked for Wenner Media as head of Rolling Stone Press, while I became a stay-at-home-dad. (Though Jack and I had a circuit around the East Village. We didn’t stay home much.)

Hands-on parenthood was the best experience of my life, a transformative time. I gigged and wrote little for five years, yet I knew I was logging rich material for future work (and how). I gladly turned down a couple more offers to tour as a bassist.

Three years into this new chapter, Rosanne, with whom I’d become friends, asked me to help her and husband/producer, John Leventhal, finish a song entitled “44 Stories.” I did, and she included it on her Grammy-nominated 2003 album Rules of Travel. She also encouraged me to write prose: “When are you going to sharpen your prose pencil?” she asked. (And here we are.)

My family moved to the Catskills, and I took a job as a teacher’s assistant at Jack’s hippie preschool (not unlike bartending, it turns out). After a year, my boss asked me to bring in my guitar to play for the 2, 3, and 4-year-olds. All told, about 15 kids, some having diapers changed by me. I’d performed before thousands by this point, yet I was anxious the wee ones would express displeasure, even tot hatred for my playing. One thing you discover working with very young children: generally, preschoolers have not yet learned to lie, and this is both great and harrowing. Nevertheless, I brought in my old acoustic and played Johnny Cash and Beatles songs, and experienced an epiphany: I’m good at this.

Playing live, interactive music focused the kids like nothing else, and their minds, indeed, quickened; the texture of the atmosphere changed, grew more connective, unified. They particularly loved minor key songs like “Ghost Riders in the Sky,” and a tune I wrote about getting hurt, a blues called “The Boo Boo Song,” which elicited tales of how they’d injured themselves. They showed off scrapes and scars, like bikers in a bar comparing tattoos. And I always told them, to their astonishment, that skin, bones, and hearts are stronger when they heal.

From my experiences in the preschool, I created the persona Uncle Rock, and stepped into the post-Raffi world of the Children’s Music Troubadour, now known as the “kindie” scene. I released another “grown-up” CD – Lazyeye – on which Rosanne and Kate Pierson of the B-52’s guested. But writing, performing, and promoting the Uncle Rock material took precedence. It was more fun and lucrative.

I spent several years playing many Uncle Rock shows for families, and getting good press: “Shel Silverstein meets Buddy Holly!” – New York Post. “For kids’ music with an edge, Uncle Rock is your go-to guy.” – NY Daily News. I released CDs on which I honored the darkness to which the preschool kids responded, and folks bought them. Frequently, parents told me an Uncle Rock show was the first time they’d experienced live music with their kids, or it was the first time their child had seen someone play in person. And who knew it could be so fun? It occurred to me I was reconnecting people to an ancient tradition, to music as community bonding, beyond technology or fashion, and they often reacted with a combo of surprise, reawakening, and relief.

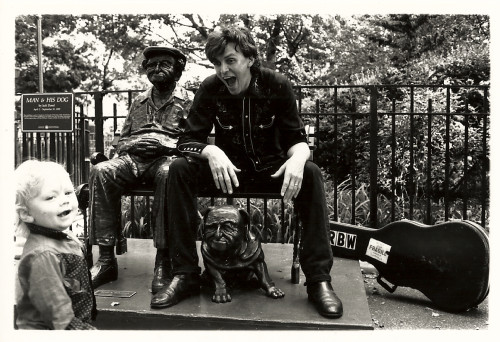

Best of all, I got to hang out a lot with Jack, who was, and remains, my favorite person. The Uncle Rock endeavor began as a father-son project, and Jack was my little sidekick, singing and vamping and getting the crowd hyped up. We had some big fun. We performed at the Austin City Limits Festival, all over Manhattan, throughout the Tri-State area, in Los Angeles and San Francisco. I wrote a song about death (made into a great video by my friend Barney Miller) and a song about how getting too many presents often makes kids feel awful. I gigged a lot, and, combined with copious airplay on satellite radio, I made a decent living.

At one gig, I was performing my usual set closer, the James Brown-inspired, “It’s Hot! (Don’t Touch It!),” on which I would yell, a la the Godfather of Soul, “IT’S HOT!” and entreat the audience to yell into the mic: “DON’T TOUCH IT!” It was a smaller-than-usual crowd, and I was miffed about that, but there was one 6-year-old who kept yelling “DON’T TOUCH IT!” on cue. He was really into it. After the show, his father approached and said, “I gotta tell you, my son’s autistic, and that’s the first time he’s ever spoken on cue. Ever. Thanks.”

My Sloan-Kettering gigs were intense, too. For about a year, I volunteered for Musicians on Call, a service that sends musicians to care centers to perform. I played mostly for kids being treated for cancer. One day, at the Sloan-Kettering Pediatric Pavilion, I teamed up with a couple of heroically funny Big Apple Circus clowns. Kids ranging from toddlers to teens were in all manner of nightmarish discomfort, which I will not detail here, and sometimes nurses (talk about heroic) sent us away. But several times our impromptu act relieved the kids, and even made them – and, crucially, their parents – smile, laugh, and sing. “Oh,” I recall thinking. “Music can do this, too.” The quickening art.

Recently, a much-copied Facebook status update was: “If you could send your teenage self a two-word message, what would it be?” I was in a bad mood, feeling poor and puny, so I wrote: “stay focused.” I’ve sometimes thought perhaps I’d have had more success (money) if I’d stuck with one thing, rather than honor the urge to bolt and take on new challenges. But in retrospect, I wouldn’t send that. Ambitions stoked while gazing at ceiling posters of Aerosmith and Jimmy Page, or while witnessing solo Steve Earle captivate Irving Plaza, did not pan out as planned, of course, but the adventures were – and remain – memorable and rich, and continue in forms I could not have comprehended at 14 (or at 25). All my strides, whether they led to successes or failures, brought me to here, to this writing, my first as music editor for The Weeklings, and that feels right. So, after mature consideration, the two word message I’d send that gangly kid, stinking of Clearasil, navigating the sweat-slicked neck of a $100 bass, is as follows: “Rock on.”

Pingback: Rock On for The Weeklings | solitude & good company

I so look forward to reading more Robert Burke Warren re: music. The world needs another snark-free voice on the “quickening art.”

Thanks, Babs! Your wish is my command.

Lovely read Robert…I always enjoy your talents in all mediums. The piece with Gandalf is a hoot!

Thank you, Tom! And yes, Gandalf ROCKS! Who knew?

Pingback: Not A Misspent Youth, Part 7: Wee Wee Pole/RuPaul and me in Marietta, Ga., 1983 | solitude & good company

Pingback: The Final Popped Culture | The Weeklings