IN MAY 1984, Samantha Baker came downstairs for school to discover something horrific: her family had completely forgotten it was her sixteenth birthday.

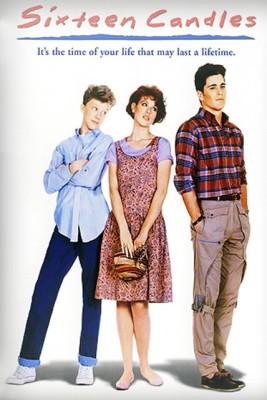

Samantha, of course, was Molly Ringwald in a fedora. The film was Sixteen Candles, and the moment was pivotal for the American Teen Movie.

Well, sure. There are other moments in John Hughes’ first outing as writer-director, which was released 30 years ago this week, that are more cinematic, more deftly comedic, more quotable. During the stretch of 24 hours leading up to Sam’s sister’s wedding to an “oily bohunk,” almost every scene is a highlight. Such as:

Sam fills out a secret sex survey (Question: “Have you ever done it?” Her reply: “I don’t think so.”) and pauses to peek at HIM. Jake Ryan. The perfect, unattainable boy she pines for. Who is staring in all his hotness right at her.

The Geek, aka Farmer Ted, aka Anthony Michael Hall, goes from being Sam’s spazzy suitor to her trusted confidant, all while sitting in a school auto shop car.

The Geek and the panties and a bathroom full of boys going, “Aaaaaahhhh.”

Weirdo grandparents squeeze boobies. Long Duk Dong gets blitzed and horny. A young, exquisitely nerdy John Cusack wears a headset. Catchphrases are born. Synthed-up background music feels organic. Everything Anthony Michael Hall does is genius. Michael Schoeffling as Jake manages to look dreamy in sweater vests and front-pocket chinos. We learn that reluctant brides and muscle relaxers really don’t mix.

At the end, Samantha runs out of the church after her sister’s wedding to yet another indignity: everyone’s left without her. But wait. The last car pulls away…and there’s Jake and his red Porsche. Both waiting. For her. Now here come the first chords of the Thompson Twins’ “If You Were Here,” and I don’t know anyone who doesn’t quietly freak out at this point.

It’s all terrific. But that first moment…Your whole family forgets your sixteenth birthday? That is drama. That gets deep into the nooks and crannies of every shitty thing you’ve ever felt about your life.

The brilliance of John Hughes was that he understood this. He got that the seemingly “small” everyday problems of American teenagers are, in fact, compelling enough to frame an entire film’s story. These problems are actually very big, and more importantly, they are very real.

In the early 1980’s, “teen comedy” meant “teen sex comedy.” There was Porky’s and The Last American Virgin and Losin’ It and Risky Business, all tales of boys trying to get laid. (Oops, I forgot Little Darlings, a story about girls trying to get laid.) Then there’s what I call the “teen California comedy,” as in Fast Times at Ridgemont High and Valley Girl.

Of course, I loved these movies. Everyone I knew did. They’re funny and have great soundtracks, so what’s not to like? It’s easy to forget that many of us couldn’t actually see them in the theatre, because they were rated R. (The one exception, for me, was Risky Business, which I saw with my grandmother, but I vowed to never speak of that again.) Most of us watched them on our newly-installed and still-wondrous cable channels and VCR’s. Which meant we saw them in our homes, on our parents’ turf. It also meant we saw them about 58 times.

I understand now that these movies were basically fantasy films. Who were these people? They didn’t resemble any kids I knew. Granted, I was a geek, but they barely even resembled kids I watched, quivering, from a distance. These films were set in the vague Other world of high school. The one I always felt like I was missing out on. Here, for a few hours, I could be part of it.

To find a teen movie that resonated with me in any authentic way, I had to go, figuratively, to Europe. Props again to HBO for endlessly airing the French blockbuster La Boum (The Party) starring a 13-year-old Sophie Marceau, and Bill Forsyth’s masterful debut Gregory’s Girl. Sometimes I could barely understand him for the Scottish accent, but I still felt a strong connection to Gregory. I, too, had impossible crushes. I, too, had dorky friends I spent a lot of time talking about my impossible crushes with. I, too, just wanted a conversation or a date or a possibility, with sex the last (terrifying) thing on my mind. What did it mean that in order to see my experiences mirrored back at me on a screen, I had to watch a foreign film?

In May of 1984, I was sixteen myself, with a freshly-earned driver’s license. My friends and I had just taken the SAT’s. None of us had puked right there on the bubble sheet, as we’d feared, so celebration was in order. We wanted to go see this new PG-rated movie with the cute guy on the poster. I picked up my friends in my parents’ Volvo, and we set out on our own for the Arcadian Shopping Mall in Ossining, NY. Turns out, this is the way Hughes wanted it. In a 1997 interview for MTV, he said, “…the movies are one of the few places a teenager can go sit by themselves or with friends and not have to deal with their parents…It’s a big part of the social experience.”

When we first meet Samantha Baker, she’s examining herself in the mirror. She’s trying to figure out if she looks different and special now that she’s sixteen, if the changes she feels on the inside show on the outside. I sat there in the theatre and thought, I have totally done that! Also, this girl is normal-looking. She looks like someone I could watch “General Hospital” with. And I actually have that same fedora.

It’s meaningful that Hughes wrote the character of Samantha with Ringwald in mind. He’d never met her, but he’d found her headshot and pinned it to his bulletin board before sitting down to write the Sixteen Candles screenplay over a single weekend. We’re supposed to believe, as Jake says, “there’s something about her,” and obviously there was. There is. She is average-special and everyday-fabulous.

(Aside #1: Hughes also created the part of The Geek for Anthony Michael Hall, inspired by Hall’s performance in National Lampoon’s Vacation, which Hughes wrote. Aside #2: They almost cast Viggo Mortensen as Jake. Molly Ringwald said he made her “weak in the knees” during a kissing screen test. I sort of can’t stop thinking about that.)

Watching the film again with my sadly critical adult eye, it’s hard not to notice the rough edges of the story. It’s sweet that Jake returns Sam’s underpants to her right before he presents her with a birthday cake, but also really creepy. We get misty-eyed when The Geek and Carolyn wake up in a Rolls Royce convertible to think they had sex but don’t remember it, but maybe it’s the beginning of something beautiful…and that’s also really creepy. Characters we like say “f**got” and “r*tard.” And then there’s the sole character of color, Long Duk Dong; hilarious, adorable, and a cringeworthy racist stereotype.

I can forgive all these things if I look at the movie as a time-capsule from a different era, but also when I consider how Hughes managed to subvert existing teen movie tropes. There’s a big school dance, but it’s at the beginning of the film, not the end. The party scene is important not for what happens in it, but away from it (Jake trying to call Samantha) and after it (the devastation of Jake’s house, Jake and The Geek bonding). There’s a Naked Boobs Shower Scene, but it’s two girls doing the ogling, and not in a sexual way but a jealous one. The parents are actually characters and not caricatures, and they make good in the end. The Popular Guy questions the trappings of his social status and yearns for something more meaningful. The Popular Girl is party hearty, but she’s very nice too. The movie is set not in southern California but an upper middle class Chicago suburb.

And in the end, nobody’s really trying to get laid. Sex is referred to and hinted at, of course, but the characters we care most about — Samantha, Jake, and The Geek — have higher priorities, even if they’re scared to admit it.

In a 1986 interview for Seventeen magazine, Hughes confessed that as a teen, he was obsessed with romance: “Most of my characters are romantic rather than sexual. I think that’s an essential difference in my pictures. I think they are more accurate in portraying young people as romantic — as wanting a relationship, an understanding with a member of the opposite sex more than just physical sex.”

For me, Sixteen Candles is about young people asking themselves, “Is it okay to feel what I feel? Am I allowed to want what I want?” Is Sam being selfish about her birthday, and crazy to think she has a chance with Jake? Ted doesn’t really want to “bag a babe.” He just wants a girlfriend; what if his dork friends find that out? (Pssst, Ted: I think they feel the same. Just a hunch.) When you finally understand that yes, you’re entitled to reject what others expect and assume about you, and yes, you should absolutely listen to your heart…then you’ve truly begun to grow up. But not, of course, without healthy and entertaining doses of angst and self-doubt.

The success of Sixteen Candles empowered Hughes to be less subtle with these themes in The Breakfast Club just one year later, which I’ll argue was his best film (and partially inspired my novel You Look Different in Real Life). The Breakfast Club, and its portrayal of identity and stereotypes, the invisible and arbitrary social boundaries of high school, felt even more realistic to me when I first saw it. In fact, when people ask me why I work in YA (Young Adult) fiction, I think back to that powerful sense of, “Wait, how did you see all the strange, secret, painful things inside my brain I thought I was a freak for feeling?” The urge to create that sense for someone else, with all the comfort and strength it can deliver, is one reason why I write what I write. I also believe that the key issues of the teen years are really the key issues of any age. I imagine John Hughes was driven by the same notions.

Sixteen Candles still sparks 30 years later because it captures, with a perfect balance of absurdity and honesty, that point in life we often wish we’d never left. You know the spot. Where love feels simple and it’s safe to dream big. Where everything seems terrible…but anything is possible.

In some ways, I live Samantha Baker’s day every day. I wake up and scan the mirror for evidence that I am changed, and unique, and deserving of everything I wish for. Then I go downstairs in my enormous fleece bathrobe, I mean fedora, to find that everyone has forgotten my birthday. Again. What will I do about it? I guess that’s where the fun begins.

Pingback: 100 Famous Directors’ Rules of Filmmaking | BRIAN KING