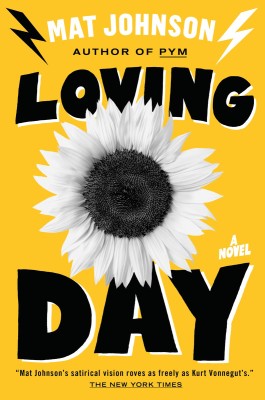

IN HIS NEW BOOK Loving Day, Mat Johnson writes that there are two types of biracial people: sunflowers and Oreos. Sunflowers are white on the outside but black on the inside. Oreos, on the other hand, are black on the outside but white on the inside. It is the juxtaposition of these two opposites that creates something uniquely different from either while retaining certain properties of both. But what if there is another way of seeing people who share dual or multiple racial heritages—not as a sunflower or an Oreo but as a combination of both entities, like a Russian Matryoshka doll all the way down to one’s DNA and the most infinitesimal particle of one’s soul? Are we as a society ready to handle a new paradigm of a sunflower with an Oreo center which inside the creamy filling contains another sunflower with a smaller Oreo and on and on into infinity—never fully being one thing or the other on the inside or on the outside, but simultaneously being both things in all ways and at all times in a uniquely beautiful and enigmatic way?

I first made Mat Johnson’s acquaintance on Twitter, drawn in by his humor and his observations about the absurdities of life and the absurdities we pretend not to notice in ourselves. It was a refreshing change to the forced humor one must gird her loins and bear on social media along with the endless array of cat pictures. And, of course, it doesn’t hurt that Mat is a handsome man. His intense gaze captivates. You’re not sure if he’s thoughtfully considering you or seriously about to snatch a knot in your ass; either way the look is magnetic and dangerously seductive. The offspring of an African-American mother and an Irish-American father Mat describes himself as mulatto (possibly better known as biracial to you and me) and that is the focus of his new novel.

Mat admits that the book’s protagonist, Warren Duffy, struggles with many of the internal monologues he himself has dealt with concerning his mixed ethnicity. In Loving Day, Warren is a self-described “sunflower”: white on the outside but black on the inside. Mat has said that while growing up in north Philly and even now, people are not sure what he is and that even though for most of his life he has identified ethnically as black, he now embraces both sides of his racial heritage equally.

I admit the first time I laid eyes on Matt’s photo on his Twitter profile and even in subsequent photos afterwards my eyes immediately identified him as black. In Louisiana, where there is a large portion of mixed racial heritages, and where I grew up, there is a strict, unwritten social code of who is black and who is white. When skin color doesn’t make classification instantly obvious such ethnic markers as width of the bridge of the nose, shape and fullness of the lips, slope of the forehead, size and set of the ears, the angle the mandible meets the skull and even the roundness of the back of the head in adults are all considered. Curly and wavy hair is suspect. The eye does a quick, subconscious analysis of body shape: the length of the torso in relation to the length of the legs, the way the arms drop from the shoulders, the setting and musculature of the backside. The ears hearken to every inflection in the voice: the tone, timbre, rhythm, and phrasing. I even had a college friend who insisted (erroneously) that “true” whites (pure-blood Anglo-Saxons) did not have half moons at the base of their fingernails and that was always a sure-fire giveaway. So trained were we to look for these characteristics of racial lineage that even living among a plethora of mixed peoples (some multi-generational), I am aware of only having called one wrong once in my life.

However, in 1970s working class Germantown and Mt. Airy sections of Philadelphia there may not have been such a historically biracially pervasive culture as in Louisiana. Looking at adorable pictures of Mat as a little boy he appears white, and yet he grew up in a predominantly black neighborhood with an African-American, divorced, social worker mother so he identified as black. Spending every other weekend with his Irish-American father, he was able to develop an appreciation for both sides of his heritage, but his primary influences were black and for the most part, the way he saw the world was as well. And he wasn’t adverse—pale skin, fine curly hair and all—to donning an Afrocentric dashiki on occasion.

And yet…Mat admits to always feeling as if he had to prove his spiritual and mental blackness to his peers to overcompensate for the physical whiteness of his skin. Such a continual need to affirm that one has a right to belong can have quite an effect on a little boy and the way he views the world around him as well as the man he is to become.

Johnson shares these traits with Warren Duffy: a comic book illustrator and failed comic book store owner and husband. At the beginning of the novel, Duffy returns from abroad after a divorce from his Welsh wife to his north Philadelphia home where he as been bequeathed a decrepit mansion by his deceased father. As he struggles to successfully deal with his crumbling legacy, he learns to his surprise that he is a father himself—to a teenage Jewish girl no less: the result of a youthful indiscretion. What follows is a sometimes humorous, sometimes poignant and always thought-provoking odyssey that sees Duffy trying to deal with fatherhood, his remaining hang-ups about his racial identity, a possible cult, new love and two crack heads that are oddly ephemeral.

Mat is a Creative Writing professor at the University of Houston and the author of the novels Loving Day (2015), PYM (2011), Hunting in Harlem (2003), Drop (2000), the nonfiction novella The Great Negro Plot and the graphic novels Incognegro (2008), Dark Rain (2010), and Right State (2012). He graciously agreed to take a few moments to answer a few questions about Loving Day, the enigma of race in America, fatherhood, writing and the publishing industry:

Tell us a little about Loving Day.

It’s the most general questions that are always the hardest. Loving Day is a novel set within a radical mulatto commune squatting in Fairmount Park, and also it has a crumbling haunted mansion, and within that world, a dad tries to connect with his daughter. What it’s about, that I’ll leave for everyone else.

I believe all writers want to tell a good story, but I believe they also have something they want to say—a message they want to get across to their readers. What do you want to say with Loving Day? Besides, you know, “Hurry up and buy me”?

I don’t have anything I want to say; I have questions I need to ask. I don’t want to come in with a definitive answer on things, because then the work can become dogmatic, and dead on the page. What I try to do is create situations that can speak to issues I’m exploring, and then see where they go. With this novel, I just started with the first sentence, and then from there let the parts come together.

What is the takeaway for Loving Day for you as a writer? How have you been personally illuminated by the issues you’ve explored in the telling of the story?

As far as the ideas, the writing of the book is only part of the process. I got some things out of it, philosophically, emotionally. But what’s more important to me and frankly more important in general, is what other people got from it. The novel doesn’t exist on its own. It comes alive in its readership. What conversations start out there. What questions start to find answers. After it’s written, the readership is more important than the artist in bringing it to life.

When reading Pym—even among the absolute hilarious moments—I experienced a deep sense of the desperation of what it must be like to be a slave—not the American South slavery horror: there was no scorching sun in your novel, no boll weevils, no piercing cotton bolls that ripped the pads of slave’s fingers to shreds and gouged underneath their nails, no lacerating whip, no backbreaking “low” cotton, no paterollers and all the extraneous terrors that has traumatized descendants of American slaves for generations. Rather, in Pym’s sterile, artic environment I got a sense of the isolation, the loss of self identity and the mind-numbing drudgery when life is reduced to mere survival, and the helplessness and crippling dependency of what it must mean to be a slave even in modern times. You go on to state that even though people in the U.S are no longer subject to institutionalized slavery, there are ways we enslave ourselves even if it is only to our lusts and to our dreams. Care to expound upon that for people who have not yet had the pleasure of reading Pym?

I think you did a great job already! So let me expand on that: this is what is so important about fiction. History can tell you what happens. And when it’s told right, it can be a tale of passion and weight. But what a novel does that a history book never could is let the reader leave their own life and directly experience the emotional life of others. And to do that, you don’t need to be literal. We’ve become accustomed to the images of slavery; it becomes almost a genre on the page. But through the fantastic, through the altering of factual reality, you can actual get closer to the emotional reality.

What do you think comedy brings to literary fiction? What are the best ways you find to interject comedic moments into your writing? When do you think humor is most likely to succeed? To fail?

I’m rarely conscious that I’m putting comedy into the work; I’ve realized my humor on the page has more to do with how I see the world than a conscious attempt at humor. Comedy, and satire specifically, works well when it’s focused on powerful absurdities. The greatest American satirical writing has been about war (Joseph Heller, Kurt Vonnegut), or about race (Ralph Ellison, Chester Himes, Percival Everett, George Schuyler, Paul Beatty, etc.), because both are powerful forces in our society, and utterly absurd.

What is your regular writing routine like? Did you approach Loving Day any differently than previous novels? If so, in what way?

I steal time then I write within that time. I have a wife and three kids, am in a full-time professorial role, plus I travel around the country and do reading and lectures regularly. I don’t have the luxury of a set schedule anymore. So I steal time wherever I can. That’s how Loving Day was written, in stolen, disconnected hours.

How much of your own history is a part of your books? How much of the real you do we get to see in your characters? Which characters have you written that you feel are the most like you?

People don’t like to hear this, because they want a character as stand in for the author—our brains demand that simplicity. But the truth is, almost all the main characters are parts of me. Not just the protagonist, who sometimes does grow from a seed of one distorted aspect of my person, but all the other major characters as well. That’s how I try to bring them alive.

I think in this book, being biracial and having a biracial lead character, people are bound to make that leap. But again, absurd: white people write novels with white lead characters all the time, and nobody thinks that makes the book autobiographical.

Being biracial, have you ever wanted to be one race or the other? If so, which race would you have chosen and why?

I think it’s natural to want to be fully accepted into the community of which you are a part. I wanted to just be black, as opposed to black with an asterisk. This is part of why thinking of myself as ethnically (as opposed to racially) black was not healthy for me. It felt like I was cutting half of me family away to fit into a definition. Your definition of self should fit you, not the other way around.

In a world with such an indelibly engraved color line, at what point did you become comfortable being a product of two races? What do you think fed into that?

I think the final moment happened when I was introduced to a person at an exclusively black cultural event to which I’d been invited. This was about a decade ago. When we met, I recognized the look on their face as they took me in. It said, You look white, and I’m going to treat you like you’re a fraud who doesn’t belong here unless you prove to me that you’re really black enough. I recognized this, because I’d dealt with this response so many times in my life. And usually, in the past, I complied, to put them at ease. But I was finally too old for that shit. So I didn’t play the game. And in response, over the days that this went on, they got increasingly agitated by me. And I didn’t give a fuck. My days of trying to make other people comfortable with my racial identity were over.

Many authors have approached the enigma of “whiteness.” Maya Angelou wrote in “I Know Why The Caged Bird Sings” that as a child she was convinced it had to do with white people’s private areas. Other authors of color have compared it to a state of mind or a sense of place or privilege. I had a childhood friend who was sure it could be found in just the right bottle of shampoo. Unfortunately, I don’t know that literature (even literature written by many black authors) has probed the equally enigmatic concept of “blackness”, as if blackness is no more than, at best, merely a foil for its polar opposite or, at worst, a void that all good things disappear into. As a man who is both black and white what is your concept of “biracialness” as it pertains to the combination of the two?

I don’t really think I’m black and white. As far as the racial caste system, I’m black. Ethnically, I’m African American and Irish American. I have privileges in this country for looking white, but they only go so far. And even if we call White American an ethnicity, it would be one defined by majority dominance, and the worldview that causes, and I don’t share that worldview. So I don’t prefer the word biracial. I don’t even like mixed, really, it’s too vague. For first generation people with black and white parents, I like mulatto. People think it comes from the word mule, but it predates that considerably. It’s the only word that actually says what this experience is about, historically.

Did growing up biracial and being an only child affect how you see the world, how you saw yourself?

I think everyone sees the world based on how, where, and with whom they grow up. With white people, because they see their experience as the normative universal, they often don’t realize how heavily their whiteness effects there perception of reality.

As a professor, what is the best writing advice you can give your students? What writing advice have you come across that you would tell them to disregard completely?

One of the hard things about writing is that everyone has there own path, their own demons to conquer. But for a beginning writer, my advice would be, Just write. Write through the dreck that everyone has to produce to get to the point that they can do what they want on the page. Make time. And if you can never bring yourself to write, if it’s something you just feel guilty about not doing, walk away and do something more fulfilling with your life.

All authors today are encouraged to have a significant online presence. What are your thoughts on that? Do you think it adds to or detracts from the writer’s mystique?

Mystique is dead. I don’t know if that’s a totally bad thing; it humanizes the artist. But yeah, we’re still adjusting to what this hyper-present world means. This is the end of being able to hide anything.

When I got on Twitter in the spring of 2008, it was just an utterly impractical little site where a bunch of my writer friends were goofing off. There was no retweet button, so everyone’s reach was limited. There wasn’t even in-site picture hosting, or favorites. So it was a lot quieter. When the retweet button came on, overnight it became a broadcast medium, and that’s when interaction changed dramatically. I just happened to be sitting on the volcano when it blew up, and you can’t advise young writers along those lines: look for the next internet volcano and sit on it, and then your career will blow up.

In Loving Day, the protagonist, Warren Duffy, has to learn very quickly how to be a father. What did you learn about being a father from growing up in a single parent home? What have you learned about being a father since you’ve become one?

The single biggest lesson, which shifted me from prolonged childhood to adulthood, was simply learning that your life is not about you. Before, everything I did was for myself, or someone I chose. Then there’s this little stranger, and I have no choice but to accept that every day I get out of bed for her. That was a wake up, literally.

What have you learned about being a father now that your children are older and their needs, and consequently their ways of viewing you, have changed?

When I started Loving Day, my oldest was only five. I wrote the scenes in the first hundred pages of the book imagining what it would be like to have a teenage daughter. By the time I finished, eight years later, she was a teenager. I’m in awe of that now. Ultimately, although the character is not her or my younger daughter, I was able to see into a world and way of interacting through them.

Being a father made me an adult. And not instantly: it took years, and the process isn’t over. But without this experience, I wouldn’t have been able to mature as quickly. I used to look at the world as if I was the protagonist. Now I’m reminded daily that I’m just another character in an ensemble. My day, my time, my money, it’s not focused on me. It’s focused on my children. That’s humbling.

As a writer, how do you define success? Do you think there is a definition of failure for a writer?

At this point, for me, success has been about growth, and fulfilling potential. The farther I push my work, the more I feel successful. But it’s a constantly moving metric, so I don’t know if you ever feel like you’ve made it. I doubt it. You can always make more.

What published works are you most proud of and why?

That’s like asking which of your kids do you love most. I’m proud of all of them, for different reasons. I also wish that each had been able to do more.

What are the challenges you see in writing and publishing novels when the protagonist is other than white?

The biggest racial publishing challenge to a novel isn’t the cast of the characters; it’s the race of the author. White audiences want books by white people. White publishing wants to make money, so reinforces it by throwing their money behind white authors disproportionately. If you’re not white in publishing, you are at an immense disadvantage. Check the VIDA numbers as they pertain to race this last year. They’re horrific.

Do you have any ideas on what can be done in the publishing industry so that it is more receptive of diverse authors? If you were invited to give a speech on this very topic, what would be your talking points?

We need more senior editors, VPs of Marketing and Sales, who aren’t upper middle-class Caucasians. The readership is there. It just isn’t being tapped effectively. In publishing, the real money comes in at the top of the food chain, and people wait it out on substandard salaries (to live in NYC) in hopes that they’ll make it to a high paying position. It’s a 1% business model. So if your family isn’t subsidizing you, and you don’t have a wealthy spouse, it’s hard to hold on long enough to make it to the top. And at the top, there isn’t a great appreciation of diversity either. Not a ton as far as the books published, and even less when it comes to sharing power.

In a video interview you gave with the University of Oregon you touched on the concept of “The Emperor’s New Book” in that there is a tendency of a lot of authors of contemporary literary fiction to write novels that are so boring or abstract as to be unreadable as a litmus test of the reader’s intelligence or superhuman powers of concentration. You contrasted this to authors of the 19th century who were able to create smart literature that still retained a riveting, page-turning quality. What do you see as the challenges of literary fiction today if it is to remain a viable part of the publishing marketplace?

Honestly, I can barely manage what I have to do with my own books; the idea of thinking about what publishing has to do overall is overwhelming.

I will say this, if publishing continues to be overwhelmingly white and upper middle class and higher, it’s doomed like baseball. Did you hear the Chris Rock riff on how baseball has gotten so white and insular that it’s dying? The same exact thing is going on in publishing.

What do you think your books bring to the table in the ever ongoing discussion of race relations?

I think writing about mixed experience is a healthy reminder that the racial caste system we’ve created is bullshit. I’ll take that as a win.

What is on the horizon for you? What are you working on now and what do you hope to accomplish with it?

I like to switch things up; I get bored. Right now I’m playing with a historical novel set amid the Irish riots that targeted black Philadelphians between 1834-42. It’s wild, the black community was actually doing pretty well, and the Irish resented them for it, and the Nativists pit them against each other rather effectively. Philly is my home, and my Irish ancestors arrived in Philly in 1832, so I feel connected to both sides. We’ll see.

You start with a dream. You build a physical structure around the ghost images in your mind. Sometimes, the gravity of reality pulls it down. But sometimes you get lucky, and when you’re done, something that’s never existed in the world is sitting there before you.

Fantastic interview!

Thank you, Gabriel. Coming from you, that is a compliment I will cherish.

I’m opposed to Mat Johnson’s acceptance of the one-drop myth. If you look white then you ARE white. To say otherwise is racist. “White” is also multiracial.

http://melungeon.ning.com/forum/topics/5th-union-presentation-by-a-d-powell