BUZZING FROM A COUPLE VODKA SODAS and a thousand-dollar slot win, I didn’t notice them at first, but slowly they began to fill the casino floor. They were the faithful: men and women of all ages, some grey-haired, some conspicuously tattooed, wearing Monkees tour T-shirts and jeans, hooded sweatshirts and green Mike Nesmith hats. They looked incongruous in this crowd of gamblers. But there was one reason why they and I should all be here tonight: to see the Monkees play. The three Monkees, the only three that survive.

Now and then, pilgrimages feel necessary; friends of mine had gathered to watch the new Boyce and Hart movie, for instance, a documentary about two of the Monkees’ key songwriters, which had previews in New York and LA. But I was alone here, an island among my fellow ticket holders who were chatting and holding hands. We all abandoned the machines that were eating our cash and thronged the back of the room where the concert hall entrance was. My excitement was more nervous than happy—never having seen these guys but knowing so much, both good and bad, I had no idea what to expect.

How much do you really know about the Monkees?

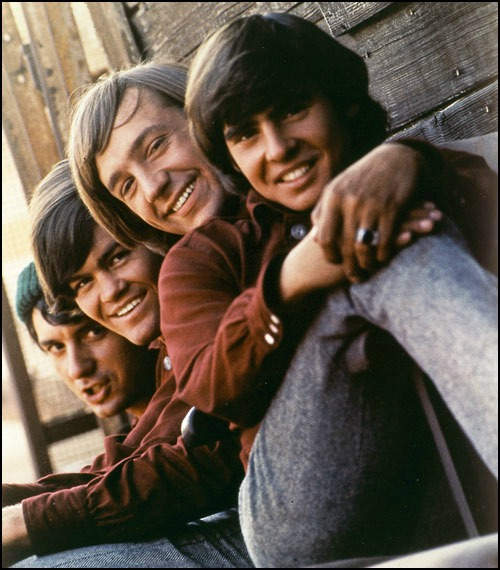

If you’re the average person with casual Monkees awareness, you probably think of their TV theme song, or “Last Train to Clarksville,” or another of the hits that made them stars; plus, more than with other bands, you know what they look like. You can likely picture them “performing” “Daydream Believer” in that sweet tableau: Peter Tork in his love beads bent over a little upright piano, the others crowded around him. Micky Dolenz, puffy-haired, shakes a tambourine; Mike Nesmith, having traded the green hat for a rad pair of aviators, plays a guitar. Davy Jones jumps around in his red double-breasted Monkee shirt, shuffle-dancing and singing the verses lustily.

It deserves to be iconic: the song (written by the Kingston Trio’s John Stewart) came late in the TV show’s run and late in the brief window when all four members could stand each other. It is a near-perfect anthem. Loveliest by far of the orchestral numbers that became Jones’s stock-in-trade, it’s simple and perfectly suited to his fine, froggy voice with its Manchester brogue, a voice bursting with character.[1] You, with but a passing interest in the Monkees, could scarcely find a better way than “Daydream Believer” to appreciate them.

OK, now pretend you like them a little more than that. You are more like me—one of those nerds at the casino, a Monkees enthusiast. You have seen all the episodes of the TV show, The Monkees, and you have heard all the music by the band, The Monkees. You’ve watched their hallucinatory, self-parodying movie, Head; maybe you even enjoyed it. You’ve read books and watched documentaries about the Monkees’ cultural moment, detailing the myriad ugly sides of their sunshiney image. Information you pick up is so meaty, so fascinating, it continually leaves you wanting more. (NOTE: please see APPENDIX to learn many Monkees facts in chronological order.) You’re the kind of person who has gone to see them in concert since the Sixties, which I was doing at the swank Borgata Hotel, Casino & Spa in Atlantic City that evening. Seeing my first-ever Monkees show at 36, I was smack in the middle of the show’s age demographic—a fact perhaps surprising to some (aren’t their fans all fiftysomething Generation Jones kids?), but not to me.

Get further into Monkees lore, and you’ll encounter their true fandom: the girls. Females still continually air their lovestruck musings about the Monkees—much of this fan-penned material is well-written and interesting; often it’s openly lascivious. (From the monkeesconfessions Tumblr:[2] “I would get down on my knees for all four of them in this picture… and I would take my time.” “I want them to play at my birthday party. And then I want them to kiss.”) It’s hard to find a Monkees video that doesn’t have girls in the comments, declaring their infatuation without shame, posting the typed equivalent of shrieking and swooning.[3] These ladies may have been fans since childhood, but more probably they’re discovering the show now, on the new computer they got for sixth-grade graduation. My own entrée into this world came at age seven or eight, when channel 9 showed them on Saturday afternoons, between Gidget and Lancelot Link: Secret Chimp, amid ads for Coppertone and press-on nails. My parents dreaded the moment at dinner when I’d start to recount that week’s episode: Do you know what, the Monkees was really good today! I would take a nap after the show was over, to think about them undisturbed, and I have no doubt this ritual would have gotten steamier if it had begun when I was, say, twelve. As it happened it wasn’t until adulthood that I bought their records, learned their story, and came to admire them in earnest. Call it regression.

***

Having arrived in town hours before the concert, I’d spent the day in the casinos. I love slot machines, another innovation that looks like a cartoon but is all too adult. Fortune was with me; I won my next month’s rent betting on slots named after The Price is Right, Cheers, Superman, various Disney movies, Lord of the Rings, Sex in the City, The Wizard of Oz. Later, when I returned home to my friends, the joke went that it was a good thing the Borgata didn’t have a Monkees machine or I might have missed the show altogether. (There is such a thing, though—you can spin the reels and come up with five Mickys—just like there have been dolls, candy cigarettes, and countless other merchandise over the years bearing their names and likenesses.)

With their legend to accompany me, I had enjoyed an eerie but thrilling day of beach sunshine, electronic bells and money. It had seemed proper for me to be alone, but as everyone filed into the venue I wished I had a friend to share this with. Walking alone into a Monkees show made me feel uncomfortably like a gawky tween who buried her face in teenybopper mags. Again.

Time has been a boon to the Monkees, with new and younger fans cropping up whenever the show goes into syndication. Before channel 9 they had been on MTV and seen a giant surge in popularity that sparked their first reunion. Later came Nick at Nite (I remember being outraged that my Nickelodeon shut down just as The Monkees was going to begin, because we hadn’t paid for the new network). And now all the episodes are online, placed in meticulous order by a YouTube user named “Torkgasmicgirl8.”

They’re worthy of this attention. The songs are fantastic, of course, but you could watch the show on mute and still come away with a crush on those guys (it might even happen faster like that, considering the thinness of the plots). Exuberant Micky, sunny boyfriend, has his dish face and little-boy grin; Davy, with thick eyebrows and ruddy lips, has a deeper, more brooding handsomeness. Peter is soft, gentle, adorable—like a brown-eyed animal you want to touch. But Mike is most compelling, the beanpole kid duded up in wool hat and sideburns that do little to disguise a cleverness, a sly magnetism.

OK, but the songs. As I write this, I’ve been playing the Monkees on my iTunes—it’s counterproductive. As with most of my favorite music, I can’t listen to the Monkees and write. I can’t listen to the Monkees and do anything. Monkees lore says much to vilify Don Kirshner, the hitmaker who banned the four Monkees from playing their own music. Kirschner enforced that ban, before the famous uprising where they insisted they should, ousting him. But he’s also the mastermind who oversaw the likes of “Last Train to Clarksville,” Boyce and Hart’s jangly, driving powerhouse; and “I’m a Believer,” Neil Diamond’s masterpiece of sing-along pop. I’m grateful, daily, to live in a world where these songs exist. Would Kirshner have given them others as good if they’d stuck with him? The Monkees didn’t much like him; they didn’t even like the tunes. But it’s irrefutable that he made some of the best records of the 20th century. Bringing together genius songwriters and producers, expert session musicians, and the vocal talent of Micky and Davy,[4] he struck gold.

I also love Mike Nesmith, who is a breed apart, standing at the three-way crossroads of pop, rock, and country music in a way that few others have ever done with such success. Mike was the oldest and most experienced of the four, already having penned many songs before being cast in the show, and he insisted on writing and producing his own work from the beginning. Good that he did, so that we have the jaunty “Papa Gene’s Blues,” the amorous force of “Sweet Young Thing,” the surprising funkiness of “Mary, Mary.” Eccentric, difficult, pioneering: who better to topple Kirshner when the time was right?[5] When he sings, you can hear it—his will to power.

Next we have Headquarters, the Monkees’ valiant effort to emerge from under the thumb of management and silence critics who hated them for being fake. Funny and raucous, it’s full of imperfect charm. That said, so much on it is perfect. In “For Pete’s Sake,” Peter uses an exciting groove to advance his hippie message of love and freedom. “Shades of Gray” is a little pool of sadness voicing an idealist’s real frustration with the world. And Micky stuffs a song with the impressions of an overwhelmed, incredulous tourist in “Randy Scouse Git”; he is telling the story of when he went to England, befriended the Beatles and met his future wife Samantha Juste. The great pity of this album is that, due to their inability to work smoothly together as a real band, they never had another like it.[6] Pisces, Aquarius, Capricorn & Jones, Ltd was gorgeous, The Birds, the Bees & the Monkees a mite less so—but those two later productions went back to being slickly professional, the four Monkees once again ceding most of the musical work to others. Tork was the first to leave, followed by Nesmith a year later. Two albums were made with just three Monkees and one with just two, before the group dissolved.

It was only recently that I saw Head for the first time. Jesus, what an ordeal. The Monkees’ feature film (really the film of their producers, Rafelson and Schneider, who went on to make Easy Rider), star-studded[7] and crazy, is interesting as a cultural document only, demonstrating how the band—the entire project—fell apart. The film has no plot, but is a series of trippy images and vignettes all speaking, none too subtly, to the Monkees’ failure. Micky leaps off a bridge in the very first scene, appearing to drown; the boys are directed to jump up and down on a giant head and pretend to be dandruff; director and screenwriter break the fourth wall to barge in on a diner sequence, shutting it down. Watching Head made me sad: unlike the Monkees it isn’t cute or charming, and its avant-garde nature seems to serve no purpose but to belittle them. Yet for a fan, the movie holds the fascination of a car crash. The soundtrack is gloriously redemptive, a tight package of six songs that are all adventurous and lavish.

***

Davy Jones died of a heart attack in 2012. He, Micky and Peter had been touring a fair amount—Mike, with many post-Monkees projects and no need for money from the band, stayed out of the picture. But now, with Davy’s passing, Mike was back in the fold and performing with the Monkees again. How weird. They are so deliciously weird, this group who for fifty years have appeared on lunchboxes and been championed by mere children. Their inherent contradictions are baffling: they’re both mainstream and experimental, both teen idols and cult figures, both contrived and genuine, both tacky and honorable. (Along with many, I’m eager for the aforementioned documentary Boyce & Hart: the Guys Who Wrote ‘Em, about the songwriting duo important to the boys’ success, which aims to show the most human side of Sixties record-producing mania.)

The Monkees was a machine, painstakingly created by visionaries, helped along by an army of commercial talent. But then, at the heart of it, there were the Monkees. The best thing the show’s producers ever did was to decide their fictional band should be four real boys, actors in the roles of themselves. And they—those boys—were who showed up in Atlantic City that night, who would never disappoint.

***

As soon as I sat down in the luxurious, plush-seated theatre, my fears were gone. I was so impressed, though “impressed” is an after-the-fact emotion and while it was happening, I was mainly just shrieking and swooning. Of course, the candy-colored images of Sixties television being inextricably linked to the band’s myth, there must be a film to show to the audience between numbers. So a screen at the top of the stage showed clips. We saw Davy in street clothes going My ‘bag’? I don’t get that! at his casting interview. We saw Micky and Mike do a half-dozen takes of the same dialogue, ruining them all by giggling.[8] Peter sat astride a pony, pulled at its mane and then pulled his own tawny hair. Micky did James Cagney: Youu dirty rat, you killed my brothahh. Mike gave a tender kiss to a mannequin in a store. They frolicked on the beach, in the Monkeemobile and into your heart.

The concertgoer seated next to me was a little girl of about eight. “That’s them now?” she asked her father, incredulous, when she saw a slide that depicted the three Monkees in the present day. “They’re old?” As soon as the music started, though, she quit complaining.

All three can sing as well as they did in their twenties. This is amazing for anyone but a particular feat for Micky Dolenz, who has a beautiful, bright tenor and always did much of the heavy lifting on vocals. Dressed in his now-trademark fedora and rectangular sunglasses, he ran around the stage throughout the set, got behind the drum kit early on and would return to it for the songs they played off Headquarters (that and Head were the night’s best-represented albums, to my delight and many of the non-nerds’ confusion). Ever a geyser of energy, Micky appeared to fill the role of the group’s bandleader[9] and hype man, public face and spiritual center all at once. But nothing could eclipse his voice.

The hardworking Peter Thorkelson played piano, guitar, bass, and banjo over the course of the show. On TV Peter used to have a gentle and naïve aspect; a deer-in-the-headlights expression interrupted now and then with a dimpled smile. Here he was puckish, sarcastic and in control. By gesturing and pulling faces during “She,” he’d get us to shout Hey! each time it came up, but then made the so-so motion with his hand as if we hadn’t done it that great. Best, he got to sing lead on his own songs: “For Pete’s Sake,” “Can You Dig It,” and “Do I Have To Do This All Over Again.” (The first two feature Micky singing on the records.) He killed. Maybe this is a fan’s misinterpretation, but to me he seemed rather sad as a young man, never mind his reputation as a Hollywood partier. Now Tork is over thirty years sober and a cancer survivor, looking good. From the stands I felt oddly proud of him.

I wondered how many had come just to see Nez. No, silly, he didn’t wear the hat. Plenty of middle-aged women in the crowd were sporting it, however—an homage to the wryest, stubbornest and most enigmatic Monkee, their favorite. And Nesmith, guitar slung around him as he occupied stage left and never wandered, delivered. What a treat to hear him sing so many of his Monkees tunes, starting with “Papa Gene’s Blues.” The second song in the set, it was the first to make me cry into the sleeve of my Monkees tour hoodie; it sounded so true, so much like I imagine it always has. Michael Nesmith, the Texan songwriter and singer, is a miraculous combination, embracing a few different genres but with a strange extra ingredient that’s not quite psychedelic, vaguely mystical. He showed it, from the joyousness of “The Kind of Girl I Could Love” to the laid-back rambling of “You Told Me” and “Sunny Girlfriend,” to experimental intricacies in “Tapioca Tundra”—while wearing sparkly slippers, a Repo Man T-shirt under his blazer. The professorial beard he maintained for so many years post-Monkees was gone, the better to show his face of wisdom and cool appraisal.

I’d been scared to hear any schmaltzy between-song patter about the departed Davy or any requests for applause or silence. There was none of that. Instead, after performing all but one of the songs from Head, the three survivors left the stage and let a film play in the darkness. It was the missing piece, Davy’s romp through “Daddy’s Song” taken straight from the movie.

From a narrative standpoint Head may be a confusing mess, but it is visually sumptuous, with its shimmying bellydancers and color-saturated mermaids, its lone Coke machine in the desert. And the music in it represents the Monkees’ creative zenith. Celebrating his song-and-dance man status—his delightful squareness—Davy tapdanced a duet with Toni Basil and wore two tuxes, the far-out edits switching his clothes from black to white midstep. The song’s lyrics, which skirt the line between twee and creepy, are very poignant today: Years have passed and so have I / Making it hard for me to cry.[10] In an hour of consummate showmanship, up until now we had barely thought to miss him. But this was the moment to remember Davy Jones’s hustle, that liveliness and spark.

Once the film ended, quiet stole over the theatre. And then they did “Daydream Believer.” Still in darkness, the familiar piano intro (Dinda dinda dinda dinda, dinda dinda dinda dinda…) proved to be Peter playing a Korg keyboard. The lights came up on him and Micky with their heads together, singing the tribute in unison.

On the other side of the stage Mike, standing stately and grey, an old man, began the second verse by himself: You once thought of me as a white knight on his steed. Micky floated over to his side to join in with a harmony, pretending before this posh casino crowd that neither of them had dollar one to spend. How much, baby, do we really need?

It can be assumed all three sang the chorus together, but I don’t remember, because at that point it was our turn. The audience sang the chorus, and everyone knew it. In that moment it was 1967 and we, the little sisters of Beatles and Stones fans, had found the group we’d love forever. Listen to what they became, these insane boys who two years ago had never even met! The “Daydream Believer” spectacle was sentimental and manipulative, clearly designed with the intent of leaving no dry eye in the house. You better believe it worked.

“Well, did you like it?” I asked my neighbor, the eight-year-old girl, once the lights came on.

“I really liked it a lot!!!” she replied, jumping up and down.

“Yep,” said her dad quietly. “I liked it too.”

***

APPENDIX

Micky Dolenz, a lifelong actor in a showbiz family, had been a child star in a TV show called Circus Boy.

Davy Jones sang on the Ed Sullivan Show as Oliver!’s Artful Dodger the same night the Beatles gave their historic performance.

Bobby Hart came up with the idea for “Last Train to Clarksville” when listening to the end of “Paperback Writer” on the radio. Its lyric And I don’t know if I’m ever coming home is a veiled reference to Vietnam.

Producers Bob Rafelson and Bert Schneider placed a casting ad in the paper calling for “4 insane boys” to be in their series and specified that auditioners must come down from their drug-induced highs before the interview.

Stephen Stills (Buffalo Springfield; Crosby, Stills & Nash) might have become a Monkee but recommended his better-looking friend Peter Tork instead.

Mike Nesmith was the only Monkee to respond directly to the newspaper ad. He auditioned wearing a green wool hat with a pom-pom on top; as the producers were trying to decide who to cast, they kept coming back to the boy they called “Wool Hat.”

Head was written by Jack Nicholson.

Both Micky Dolenz and Mike Nesmith tried out for the part of Fonzie on Happy Days. They were rejected as being too tall to act alongside star Ron Howard.

Nesmith, the wealthiest Monkee, was the writer/producer on about 20% of the band’s songs. He later inherited millions from his mother, who invented Liquid Paper, and became a video artist with a hand in creating MTV. He was executive producer of the film Repo Man.

Micky Dolenz moved to England and had a decade-spanning career there as a director of children’s TV shows.

Davy Jones, who before the big time had trained to be a jockey, continued riding and finally won his first championship horse race at age 50.

***

[1] The recorded version also begins with a tiny, cute back-and-forth worthy of the series, when producer Chip Douglas calls out the take number before Davy, not having heard him, asks “What number is this, Chip?” and then laughs about everyone being on his case because he’s short.

[3] “Micky, Micky, Micky.You lovesick goof. First you look down before you look up (1:00), you keep on walking- right into April (6:01), and you fall off a table (15:27). Micky’s sooooooo sweet when he’s lovesick! His face at 6:14- 6:16 is so… awwww so cute!!! ♥ I also want to have been in April’s place at 16:15! Ah that sweet adorable goofball! WHY CAN”T I HAVE BEEN IN JULIE’S PLACE? Some time-travelling required, yes, but I want to do that anyway. Peter in the washer was pretty darn adorable too.” –mickysgirl4ever, posting in 2012

[4] Peter Tork, who came to the project as a working (though not an accomplished) musician, was the Monkee who found himself most short-changed in the beginning. In interviews he describes the first time he was invited to the studio to check out the band’s new song: he brought his guitar, hoping to add a layer or two of melody, then was crestfallen when told the track was already finished.

[5] When Don Kirshner offered each Monkee a quarter of a million dollars in the Beverly Hills Hotel—to record “Sugar, Sugar”—Nesmith angrily fired him at the meeting, putting his fist through a wall. “That could’ve been your face, motherfucker!” he apparently said to Kirshner’s lawyer.

[6] In the spirit of it, though, they wrote and played the entirety of the reunion album Justus in 1996.

[7] Appearances include Annette Funicello, Frank Zappa, Victor Mature, and Sonny Liston.

[8] MN: Hey, that’s a groovy button. What’s it say?

MD: ‘Love is the Ultimate Trip.’

MN: Oh, that’s a nice thought!

MD: Well that’s a nice button, what’s it say?

MN: ‘Save the Texas Prairie Chicken.’

[9] They had a medium-sized, excellent backing band that included Mike’s son Christian Nesmith on guitar and Micky’s sister Coco Dolenz on backing vocals.

[10] Written by Harry Nilsson, and so has he.

Evan Davies did a great interview on his WFMU show with director Rachel Lichtman of Boyce & Hart: The Guys Who Wrote ‘Em (which premieres soon!). I loved it. You can hear them talk Boyce & Hart & Monkees, and thrill to lots of Boyce & Hart songs, here:

http://wfmu.org/flashplayer.php?version=2&show=54895&archive=95411

Simply desire to say your article is as astounding.

The clearness in your post is just excellent and i can assume you’re

an expert on this subject. Well with your permission let me to grab your feed to keep updated with forthcoming post.

Thanks a million and please keep up the gratifying work.

Antidoti vardenafil erettile disfunzione prezzo mg rimedi rx farmacia italia alla consegna effetti del della cialis nonna 20 http://rxfarmaciaitalia.com

Rx mg pharmacy rx how long cialis

Wonderfully felt and written. The last few months I have become a fanatic and you have encapsulated so much for me. It’s been a few years, bit I hope you write about the boys again sometime soon. Thank you for this piece.

Расшифровка рейв карты дизайн человека рассчитать карту бесплатно с расшифровкой на русском бесплатно