Over the past month we’ve been excerpting Tessa Laird’s social history of the spectrum A Rainbow Reader. Last week in Part V she wrote of blue the color of cops and commercials. Here in the last installment Laird talks about death and violets.

MY MOTHER AND I returned to New Zealand from Papua New Guinea in 1974, and everything seemed bleached out and faded. We were living in a flat in the drab eastern suburb of Ellerslie, and my mother was working in a factory where a white rabbit with red eyes sat gloomily in a cage. My mother explained that the rabbit was for testing products on. A week later, she told me her boss, a kindly man in beige slacks, was sad because the rabbit had died. I didn’t realize it then, but my mother was sleeping with him. I’m not sure what their arrangement was. It probably took place while I was at kindergarten, where they made me wash my mouth out with soap. I had said “fuck,” with great satisfaction, to the first person that had walked past the kindergarten gate. I was given a cake of soap and a toothbrush, and made to lean over the old concrete tub, brushing my teeth with the gag-awful substance.

Ellerslie was like Dorothy’s Kansas – everything was flat, colorless. The local children weren’t particularly friendly, but one day they coaxed me over the fence – they were playing in their backyard, which boasted a rudimentary veggie patch. Even the plants seemed colorless (green is grey in New Zealand, the omnipresent backdrop to everything). A pansy’s purple face was the only color for miles around. I stared at it intently, as though it were a portal to another world – a world of color, beauty, vegetable wisdom. A world far away from concrete-block flats, solo mums and sad men in slacks who killed rabbits. The purple pansy world was a world of velvet flowers and animals, faeries and festivities, fireworks, flashing lights in the sky.

Pansies were extraordinarily popular in the Victorian era, reproduced on postcards and writing paper. In French the flower’s name puns with the verb penser, to think; consequently in the folk wisdom known as “the language of flowers,” pansies symbolize “loving thoughts.” Claude Lévi-Strauss illustrated his famous tome on patterns in indigenous philosophies, The Savage Mind, with a bunch of pansies, for in the original French, La Pensée Sauvage can just as happily be translated into “The Wild Pansy.”

But while we think about consciousness and perception, let’s not forget the animals who see the same flowers we do but utterly differently, as if in an alternate dimension, or on another planet. Bees are backyard Martians, or better yet, Venusians, seeing ultra-violet beyond the spectrum that humans can fathom. To the bee, the shaggy golden globes of sunflowers are a rich shade of violet. Which begs the question – what color are they, really? Since bees have been around far longer than we, and since the flower evolved in tandem with the bee, wouldn’t it be fair to suggest that the sunflower is ‘truly’ purple, and that our incapacity to decode ultraviolet misapprehends it as yellow? Or is the flower both these colors, and more, simultaneously? For the color that we see is the very absence of that color in the object; what it cannot absorb, it reflects back, meaning that everything you see is at best a kind of illusion: maya, in Sanskrit.

How the bee sees color from a series by David Pye and Lars Chittka on artlink.com.au

Perhaps this was what I was thinking about when I was transfixed by the face of that pansy, and pansies really do have faces, like dog faces, clock faces, faces with something to tell you. Perhaps the pansy wanted to tell me that bees not only see in ultraviolet, but can sense the earth’s magnetic field, that they are the ultimate synaesthetes, for whom shapes have fragrance,[1] and that they dance directions to other bees. Tested on a space shuttle in zero gravity conditions, their ability to reproduce and construct combs remained unimpaired.[2] The bee, truly Venusian, lives outside of Newton’s earth-bound laws: impervious to gravity, and seeing beyond the prescribed colors of the rainbow.

Animals, it seems, have no respect for the spectra that circumvent human experience. The bee sees ultraviolet, while the bat hears ultrasound frequencies beyond our range. Using echolocation, bats send out signals to hear how they change when they bounce back – building a mental picture of surroundings based on infinitesimal sonic variations. Humans mimic this technology in order to detect enemy aircraft, or photograph a fetus in the womb. Bat-detectors convert echolocation to a lower frequency that humans can hear, and bat navigation systems sound like a series of clicking noises – like a Geiger counter measuring radiation, or anything else invisible but real.

~

So what do colors we can’t see and sounds we can’t hear have to do with violet? Violet is the last color of the spectrum – the closest we get to the unknown. Perhaps for this reason violet in the chakra system comes either at the third eye of all-knowing or in the crown of enlightenment depending on who you listen to. (Like the flower and the bee, no one can agree on color). Violet has associations with death – with crossing over to the other side – a world in which Newton’s laws of gravity and color no longer apply. Victoria Finlay, a journalist and color historian, suggests that it was precisely because violet is the last color in the spectrum, symbolizing both the end of the known and the beginning of the unknown, that it was deemed a suitable mourning color in Victorian England.[3]

Max Nordau was a 19th century social critic who wrote a book on “degenerate” art. He claimed that purple was appropriate for mourning because it has “a depressing effect, and the unpleasant feeling awakened by it induces dejection in a sorrowfully-disposed mind.”[4] Nordau saw this debilitating “lassitude” as taking over the art of his day, the “violet pictures of Manet and his school” an expression of the “nervous debility of the painter.”[5]

Manet’s Olympia: “the violet pictures of Manet and his school” = the “nervous debility of the painter.”

Science writer Philip Ball writes in Bright Earth about the effects of new chemical colors on painting, noting that the Impressionists’ penchant for purple made them subjects of derision. They were accused of “violettomania,” “and even the more thoughtful Huysmans regarded them for a time as afflicted with ‘indigomania’, as if it were a genuine collective disease, a species of color blindness.”[6] Monet, an empurpled madman, proclaimed “I have finally discovered the true color of the atmosphere. It’s violet. Fresh air is violet. Three years from now everyone will work in violet.”[7]

‘Visual purple’ is the name of a pigment in the human retina which is responsible for night vision – and most people imagine the underworld or the afterlife as continuous night. Emily Dickinson once warned of the pomp surrounding death: “None can avoid this purple.”[8]

Colors that you can’t avoid, and colors you can’t see. Who would have thought colors could be so contrary? In H.P. Lovecraft’s short story, “The Color Out of Space,” the villain is a color, or rather, color is the description given the substance “only by analogy.” Color is not “magical” and “polymorphous,” as Michael Taussig characterizes it in his book What Color is the Sacred? but, in typical Lovecraft fashion, blasphemous and polymorphous. It is an awful, creeping substance from outer space, which, following a meteorite crash, lives in a well on a farmstead in Massachusetts, and saps the land. Strange plants thrive while animals and people are tormented and die. The ‘color’ transforms the landscape into a sick, twisted version of itself, like seeing in negative, as an insect or a Venusian or a spirit might see, looking in from the other side.

According to science there really are such things as “forbidden colors”: when opposing colors are perceived simultaneously in one place. In a recent study, optical scientists had their human subjects look unblinkingly at two opposing colors side-by-side and tracked eye positions, moving mirrors in order to stabilize the color fields, so that they remained frozen in the retina. Some subjects reported seeing the “forbidden” yellowish blue or greenish red.

Evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins cautions that there are no new colors to be seen by the human nervous system. Unlike Doctor Doolittle who flew to the moon and was startled to see a dazzling new range of colors, Dawkins writes, “the hues that would greet any traveler to another world would be a function of the brains that they bring with them from the home planet.”[9]

~

Yukio Mishima’s novel Forbidden Colors looks at themes of homosexuality in post-war Japan. Mishima suggests that homosexual emotion, manifested as fanatical heroism during the war, transmuted post-war into decadence and confusion. “In that riven ground,” he writes, “it grew clumps of tiny, dark violets,”[10] a reminder that after the Victorian infatuation with the pansy was over, this soft, dog-faced relative of the shrinking violet became an insulting term for homosexual.

Forbidden Colors suggests illicit love, but also references the sumptuary laws which once governed Japanese courtly life, forbidding certain colors to be worn by certain ranks. Shades of purple burst in Mishima’s novels like love bites or bruises, while in What Color is the Sacred?, Taussig notes that mauve permeates Proust’s À la recherche du temps perdu. In 1856, the young William Perkin accidentally synthesized mauve dye from coal tar, and Taussig suspects that Proust, like the Impressionists, took to the new shade because, “It is the mother of the unnaturally natural colors” making “the embrace of artifice natural.”[11]

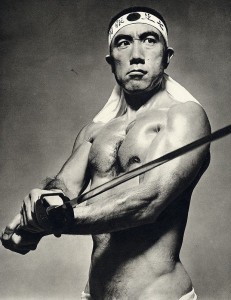

Could it be for similar reasons that Mishima writes with a violet cast? Or is it somehow related to his ethnicity, or to his sexuality, or to the fanatical nationalism that saw him commit ritual seppuku after he failed to incite a coup d’etat in 1970?[12] Sure enough, lilac and mauve have certain connotations of the ineffectual, the effeminate. Taussig notes Sartre’s irritation in Nausea, at purple seeping into the blue suspenders of a bartender, the color itself as some kind of insidious agent of feminine/effeminate deceit.

In Gravity’s Rainbow, another male accessory renders its wearer somehow the weaker: “Dr. Jamf is wearing a bow tie of a certain limp grayish lavender, a color for long dying afternoons through conservatory windows, minor-keyed lieder about days gone by, plaintive pianos, pipe smoke in a stuffy parlor, overcast Sunday walks by canals…”[13] The lifestyle depicted is thoroughly ‘civilized,’ with the sublimation that implies. Nothing could be further removed from raw masculine experience, and in that sense, modernity is about the repression of primal urges. Modernity and mauve both come to stand for the effete, the enervated, so that the color itself becomes an insulting inference of vapidity, as Theroux retells Sir William Rothenstein’s “arch remark,” that “One should always listen to Weber in mauve.”[14]

~

Mishima shares Western associations of purple with death and funerals as well as vice, and all these emotions are tangled like purple-flowered morning glory vines (which are also hallucinogenic) throughout his magnum opus, the Sea of Fertility. Penned between 1964 and 1971, these four books portray life in Japan from 1912 to 1975 and are held together with the almost willfully flimsy plot device of reincarnation. Unifying character Shigekuni Honda starts out in the first novel as a law student and ends up as a wealthy retired judge at the quartet’s conclusion. Honda believes that his old school friend, Kioyaki, an aristocrat who died young at the end of Spring Snow, is reincarnated in Runaway Horses as Isao Iinuma, an extreme nationalist, who commits seppuku at the novel’s conclusion. In Temple of Dawn, Isao is rather surprisingly reincarnated as Thai princess Ying Chan, who is fatally bitten by a cobra at the age of twenty, coming back finally in Decay of the Angel, as Toru Yasunaga, an orphan whom Honda adopts.

A lavender-colored Japanese edition of Mishima’s Spring Snow.

The entire quartet has a violet cast: in Spring Snow death is immediately entangled with purple at a funeral where women shading their faces become “dappled in violet, as though some exquisite shadow of death had fallen across their cheeks.”[15] In Temple of Dawn, the female face is again stained purple, not with flowers, but by the brash modernity of neon: “The purple neon lights reflecting on her powdered cheeks seemed to transform her fear into iridescent shell work.”[16]

Throughout the quartet, purple is associated with vice, weakness, women and sexuality. The most telling example of this implicit association comes in Runaway Horses, when the righteous Isao and his band of right-wing school friends cluster around a map of Tokyo, in which they have shaded the “corrupt” parts of the city in purple, the better to plan its violent purification.

Isao had used the purple pencil to indicate the presence of corruption, marking every critical spot. From the vicinity of the Imperial Palace to Nagata and throughout the entire Marunouchi area near Tokyo station the color was deep purple, and even the palace area itself was not without a purple tinge. The Diet Building wore a heavy coat of it, and this saturation was linked by a dotted line to the purple mass that covered Marunouchi, the home ground of the zaibatsu [corporations].

‘What’s that?’ asked Sagara, pointing to a spot of purple a little distance removed in the neighborhood of Toranomon.

‘The Peers Club,’ Isao answered coolly. ‘They like to call themselves the Emperor’s “Shield of Flesh,” but they’re just parasites on the Imperial Household.’

In the Kasumigaseki area, as was hardly surprising, the avenue lined with government bureaus, whatever the variations of shade, was purple from one end to the other. The Foreign Ministry, the chief architect of the weak and vacillating foreign policy, had taken such severe punishment from Isao’s pencil that it gave off a purple glow.[17]

~

Throughout Mishima’s novels, flowers are roughly treated, as emblems of femininity, homosexuality and the fleeting bloom of youth. In Forbidden Colors, Yuichi crushes his wife’s orchid corsage as they dance. In Runaway Horses, a Shinto lily festival features hundreds of blooms in a ritual which renders the lilies crushed and bruised. In the same novel samurai are compared to cherry blossoms, whose tenure in this world is temporary. Just as cherry blossoms fall, so too are samurai cut to the ground. Even the antics of a swallow are “like a blade cutting through the purple irises of May” for the swallow, like Isao, has “its eye upon the supreme moment.”[18] This is the moment Isao commits seppuku at the novel’s close, the blade cutting through the purple irises of his intestines.

Robert Mapplethorpe took photos of flowers in the “perfect moment” before the fall, before decay, before the fallibility of mortality. Implicit in the work is the knowledge that death is close. Mapplethorpe is dying of AIDS, hence his vanitas perform a talismanic function, a refusal of death, a celebration of perfect beauty in general and the perfect beauty of homosexuality in particular. For Mishima and some of his characters, though, homosexuality is not validated positively, merely implied negatively by a misogyny that is presented as the warrior’s distaste for feminine weakness, for “the very structure of woman is the foe of clarity.”[19] In this search for crystalline purity (and crystals shimmer and twinkle throughout the Sea of Fertility) death itself becomes the only righteous solution. Isao keeps a lily that Makiko has given him, long after it has faded and become the “mummy of a lily.” Isao calls it a “warrant for my purity” and imagines that the day he commits seppuku, lilies will sprout up and purify the stench of his blood.[20]

Good ol’ Mishima, done up as a samurai, also how he later will kill himself… In real life not just novels.

~

Aging bruises combine those sickly complementaries: purple and yellow. These are the colors of chrysanthemums heaped around gravestones when Honda goes looking for the grave of his old friend Kiyoaki in Runaway Horses.[21] Purple and yellow combine frequently in that metachromatic tome, Gravity’s Rainbow. Katherine Hayles and Mary Eiser argue that this combination signals the central character Slothrop’s dual nature. Purple, the lowest color on the spectral scale, is Slothrop’s “synthetic” self, while his “natural” self is represented by yellow, the lowest color on the pigment scale. From these primordial origins, Slothrop moves spectrally towards white, and pigmentally towards black, both states signifying dissolution. The yellow/purple combinations are used primarily in descriptions of Slothrop’s love life. Like Mishima, Pynchon stains female skin purple, or “lavender under pastel lights” while Slothrop’s “garden of love” is said to teem “purple and yellow as hickeys.”[22] The hickey is a bruise formed in the heat of passion, a reminder of the murky border between pleasure and pain. It’s no accident, then, that Greta Erdmann wears a brooch of yellow and purple irises in the scene where Slothrop starts to whip her.

The bruise in Gravity’s Rainbow is a complicated mix of the erotic and the sadistic. And, since private sadism in Gravity’s Rainbow is often a microcosm of the madness of war, the final and most dramatic eruption of purple and yellow in that novel is the bruise that a rocket firing leaves on the wounded sky:

In the iris sky one cloud, the shape of a clamshell, rises very purple around the edges, the puff from an explosion, something light ochre at the horizon… closer in it seems snarling purple around a yellow that’s brightening, intestines of yellow shadowed in violet spilling outward, outward in a bellying curve toward us.[23]

Pynchon doubles the impact of “intestines” with his “bellying” curve, and this maudlin sequence reminds me of one in Mishima’s The Decay of the Angel where the misanthropic Toru, gazing out to sea, sees in the sunset “the color of evil” which makes “the bellies of the waves” uglier. The waves become mouths “agape at the moment of death.” [24] Where others find repose and calm, Mishima writes bitterness into nature’s cycles, the Sea of Fertility becomes instead a sea of futility, as the central characters are doomed to a tidal eternal return. When describing a sunset in Temple of Dawn, human viscera are evoked – like Pynchon’s purple and yellow bomb-blast-cum-cloudburst, Mishima notes that “the colors of human intestines” are “externalised and spread over the entire sky” in a “short-lived orgy.”[25] Perhaps it is making the internal external which is morally reprehensible, an inversion of codes in code-bound Japan. Yet, I can’t help thinking of the spilling out of intestines in the ritual suicide of seppuku: the code to end all codes.

~

Victoria Finlay notes that Japan has a long history of celebrating purple: “Violet has traditionally been the color of victory in competitions, it is the color of the cloth used by Shinto priests to wrap the most precious objects of the temple, and it is the color of the costume and tassels of the highest-ranking sumo referee.”[26] The Japanese for purple is murasaki, which is the nom-de-plume of the author and central character of the classic eighth-century proto-novel, The Tale of Genji. Written by a woman for a female audience, this intimate and at times salacious work is considered the unchallenged masterpiece of Japanese literature and as such must have been enormously influential upon fervent nationalist Mishima.

Finlay proposes a linguistic origin for murasaki in murex, the Latin name for the seashell that provided Europe with purple dye. The Japanese purple-giving shellfish, Rapana bezoar, was very rare; hence most Japanese purple was made from the gromwell plant; murasaki-so in Japan. Genji, eponymous hero of The Tale of Genji, is inspired to poetry on first sight of the heroine-narrator when she is only the tender age of ten. He calls her “a little wild plant” and thus her name Murasaki is born. Like Levi-Strauss and his wild pansies or Mishima’s clumps of dark violets, literature seems to be strewn with purple petals – and pansies, after all, are one of the flowers most frequently pressed between the pages of books.

~

I press purple petals between these pages for my grandmother, who loved nothing better than plucking clumps of tiny, dark violets from the perennial patch under the scraggy banana trees at the side of the old brick house. Her life was full of sad semi-secrets which she would whisper to her cats and dogs. She was an illegitimate child made to feel sinful for her lack of pedigree, and her first beloved husband was killed in World War II. It was years before she told her own children she had been married once before: that too was shameful. She was so used to keeping her emotions in the shade, perhaps that’s why she felt a special kinship for violets, which thrive in shadows. Certainly, she preferred dainty floral arrangements; on her deathbed she felt menaced by large vases of blooms, as if they would suffocate her, or fall on her in the night.

~

Could the Japanese word murasaki have evolved from the murex shell? Philip Ball writes that the colorants in these mollusks are produced in a gland called the ‘flower’ or ‘bloom.’ At first clear, the liquid is extracted by either breaking the shells or squeezing them in a press. On exposure to air, the fluid goes through a series of transformations, from white to pale yellow to green, blue and finally purple[27] – an alchemical sequence, like the magic of a Polaroid taking shape in your hand.

The Mexican caracola or sea snail was also harvested for purple dye, but not crushed by the millions as in the Mediterranean. The snail instead was merely ‘milked’ and returned to the sea. Finlay notes that this dye, too, is light sensitive, turning from green to purple in the sun, and whimsically suggests that if someone had found a way to fix this chemical compound, we would have had the world’s first photographs: Aztec rituals and baby photos in an ancient, purple haze.[28]

Ball catalogs yet another source of purple dye, synthesized from uric acid extracted from Peruvian guano. Murexide was sold in Britain in the mid-nineteenth century under the name ‘Roman Purple’ to exploit associations with the fabulous dye of antiquity[29] and no doubt to distance the buyer from its rather less glamorous origins. Could bat guano be used just as easily? Ultra-violet dye made from the droppings of the ultra-sound animal? According to Finlay, red wavelengths bend least, while violet bends most. I imagine bats using ultrasound to find their way around bends, or even through walls, as the Museum of Jurassic Technology claims in their fanciful exhibit about the Deprong Mori or “Piercing Devil” of the Tripiscum Plateau – a bat which uses x-ray beams to penetrate solid matter.[30]

Purple ghosts language like a violet shadow. Phoenicians, inventors of the phonetic alphabet, were named the ‘purple people’ after the color they sold by mercilessly crushing sea snails. At least, that is what the Greeks called them, but who knows if they could be trusted with color terminology? They had no fixed word for blue, while Homer famously designated the sea as being “wine-dark.” Literary theorists and scientists alike have debated for years whether or not Ancient Greeks were in fact color-blind. Contemporary linguistic theory posits that color naming and even color perception is as much cultural as it is optical.

The Phoenician scratches on clay tablets – alphabetic language –enabled Homer’s words and those of his color-blind compatriots to live on in the modern world. Indeed, those scratches enable me to scratch away, as I am now, at my keyboard, linking rows of symbols together in a consensual sequence which allows you to read my thoughts – without either of us having to learn any more than 26 of these phonetic symbols, unlike the extravagant painful complexity of Japanese with its combination of kanji, katakana and hiragana writing systems.

But purple prose needn’t only be written – no, there are places where even spoken words are characterized as purple. Psychedelics guru Terence McKenna writes in True Hallucinations of his drug-taking adventures in the Amazon in the early 1970s and notes that the Jivaro shamans of Ecuador are able to see a violet substance after ingestion of the hallucinogenic vine ayahuasca. This fluid is expelled when you vomit, since ayahuasca has an irrepressibly emetic effect. It can also take form as a three-dimensional speech bubble – can be spoken into existence – or can be exuded onto the skin like sweat. Shamans look into these shiny surfaces and see other times and places because this substance is made out of “space/time or mind, it is pure hallucination.”[31] Terence’s biologist brother Dennis, who during the narrative sheds scientific objectivity and transforms, with no small degree of anxiety, into a giant insect, opines that ayahuasca’s violet aura “may indicate a thermal plasma, perhaps only visible in the UV spectrum.”[32] Like the bat that can fly through walls, “one might pierce the other dimension and have this fluid come boiling out.”[33] A “buzzing in the head” is widely reported, which seems to be “uniquely associated with these harmine compounds.”[34] So, after ingesting ayahuasca, one sees like the bee and hears like the bee.

Amazing things are revealed with the gift of ultraviolet sight. Zoologist Andrew Parker, with a special interest in the evolution of vision and nature’s optical trickery, writes that under red light, such as sunset, the Atlas moth reveals patterns of stripes, which provide “disruptive coloration” in order to confuse predators. But under ultraviolet light, the Atlas moth makes a dramatic transformation. Two snakes appear on its wings, with prominent bodies and heads with eyes and mouths.[35] Like the DNA serpents that ayahuasceros see, ultraviolet vision allows for a different, simultaneous reality to manifest.

I laughed to read that in addition to its use for mourning purple was the color of sobriety, while amethysts – the color of methylated spirits – were worn to ward off alcoholism![36] On the contrary, purple indicates slipping away from sobriety into the realm of faeries. Alexander Theroux writes, “Peyote visions are delicate floating films of color, usually neutral purples, ‘color fruits,’ Dr. S. Weir called them in 1896 after drinking an extract of peyote.”[37] McKenna referred to the shiny ectoplasm that ejects itself during the ayahuasca trip as an “obsidian” liquid, a “hologramatic alchemical fluid, a self-generated liquid crystal ball.”[38] This liquid oozed out of his partner when they had sex on magic mushrooms on a rooftop in Nepal. He looked into the obsidian liquid, and saw his own mind reflected back at him. He also saw the monk he was learning Buddhist scripture from looking into a mirror which looked into this pool of sex juice and back at his face! McKenna calls this magical polymorphous substance “translinguistic matter, the living opalescent excrescence of the alchemical abyss of hyperspace.”[39] Wow.

I had always imagined obsidian to be black and shiny, but in Veiled Brightness, a book on Ancient Maya color, obsidian is described as a form of volcanic glass that appears “in a variety of natural shades that range from gray to clouded red to bottle green.”[40] Aztec deity Tezcatlipoca, lord of the smoking mirror, invented human sacrifice. Obsidian blades were seen as manifestations of his divine body, which yielded, in contact with human flesh, the shiny rivers of blood known as “precious water,” (chalchihuitl), the greatest offering that humans could make to the gods.[41] Archaeologist Nicholas Saunders notes that ground obsidian, mixed with quartz crystal, was used in Aztec medicine to remove cataracts and leucomas. “This ‘vision sharpening’ quality of obsidian may have been a contributory factor in the origin of beliefs concerning the all-seeing nature of Tezcatlipoca, the acknowledged ‘night vision’ of his jaguar alter ego, and the divinatory power of obsidian mirrors.”[42] No wonder then, that in talking of the “vision sharpening” drug ayahuasca, McKenna mixes the vision sharpening substance of obsidian into the heady brew, also keeping a sharp eye out for creatures of the jungle that sport this same sheen, including mushrooms and beetles, and wondering if they all contain the same hallucinogenic quality – the one that makes your head buzz as though you were a giant bee.

~

As my grandmother lay dying, I returned to the place where I was born. A small group of us, hippies, healers and hopefuls, sat cross legged in a shed-sized house, similar to the one where I took my first breath. We drank a brew which was strangely sweet, like molasses, but bitter as well – sickly but full of the secrets of the earth.

And earth is where it took me, with the preverbal ague of an infant who can’t even lift its own head. My face was glued to the floor except when I was vomiting into my elliptical green bucket, which at one point became the Ellerslie Race Track, sparkling lights for the Easter Show, everything in life being one great superficially heart-felt glistering Elvis-in-sunglasses, overweight-sad-men-vomiting show. I couldn’t understand words but I could almost understand all the other languages that were being sung around me, sad songs about alcoholism and colonialism, sung by characters that looked like calaveras, sugar skulls of the Mexican Dia de Los Muertos. I wanted to cry, and shit, but mostly it was just vomiting, sweats and chills but also some thrilling sensations too – this is a body and this is a floor and these are clothes – and these are words, or parts of words, in my brain, forming chains of associations like little ladders that I can climb up, climb my way out of this mire and murk. But I like the murk, the murk is my home, I feel safe and happy and warm, like a mushroom in shit. So I lay my head on the floor, just inches away from where my murky obsidian liquid sloshes in my plastic racecourse bucket. I didn’t vomit any snakes, just an unconvincing gelatinous worm – but then, according to Darwin, worms are history’s unsung heroes. And, in the morning, with jelly knees, I buried my bile the way whenua, or afterbirth is buried, near the place where my own whenua was returned to earth forty years ago.

I didn’t learn anything. I unlearned everything, like Paul Klee and Henri Matisse, who endeavored to undo all the conditioning of the entire Western art canon. I expected visions and meanings: legible signs, which could be translated into courses of action. I was hoping for hallucinatory narratives, which could be written up and dissected, and which might even possibly give me a neat summary for this writing, like tying a big ostentatious bow on the gift I give to you, the reader.

Instead, I gibbered, and drooled, and almost shat my pants. This grueling regression was perhaps what my grandmother was going through on her death bed. It was like she was running a marathon, getting to death was such hard work. She wasn’t trying to escape Emily Dickinson’s purple, she was trying to catch it up. She got there in the end.

Robert Mapplethorpe’s memento mori, his photographs of flowers as meditation on death. Here the Anemone shot in 1989 at the height of the AIDS crisis.

[1] Preston, Claire, Bee (London: Reaktion), 2006, 21-22.

[2] Ibid, 22.

[3] Finlay, Victoria, Colour: Travels Through the Paintbox (London: Sceptre), 2002, 394.

[4] Nordau, Max, “Degeneration,” (1892) in Colour, edited by David Batchelor (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press), 2008, 43-44.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ball, Philip. Bright Earth: The Invention of Colour (Hawthorn, Australia: Penguin), 2002, 207.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Theroux, Alexander, The Secondary Colours: Three Essays (New York: Henry Holt & Co.), 1996, 128.

[9] Dawkins, Richard, Unweaving the Rainbow: Science, Delusion and the Appetite for Wonder (Boston: Houghton Miflin), 1998, 53.

[10] Mishima, Yukio, Forbidden Colours (London: Secker and Warburg), 1968, 96.

[11] Taussig, Michael, What Colour Is the Sacred? (Chicago: University of Chicago Press), 2009, 183.

[12] Mishima and a close circle attempted to incite the Japanese army to rebellion in order to reinstate the absolute power of

the Emperor. The soldiers simply jeered, and Mishima ritually disembowelled himself. These events have an eerily clear

precedent in the fanatical beliefs, attempted coup and ritual suicide of Mishima’s young hero Isao in Runnaway Horses, first

published in 1969.

[13] Pynchon, Thomas, Gravity’s Rainbow (New York: Penguin Books), 2000, 659.

[14] Theroux, The Secondary Colours, 161.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Mishima, Temple of Dawn, 244.

[17] Ibid, 128-129.

[18] Ibid, 134.

[19] Ibid, 157.

[20] Ibid, 221-222.

[21] Mishima, Runaway Horses, 254.

[22] Hayles, N. Katherine, and Mary B. Eiser, “Colouring Gravity’s Rainbow,” Pynchon Notes 16 (1985), 15.

[23] Pynchon, 683.

[24] Mishima, Yukio, The Decay of the Angel (New York: Knopf), 1974, 87.

[25] Ibid, 13.

[26] Finlay, 422.

[27] Ball, 224.

[28] Finlay, 424.

[29] Ball, 236.

[30] Museum of Jurassic Technology. “Bernard Maston, Donald R. Griffith and the Deprong Mori of the Tripiscum Plateau.” www.mjt.org/exhibits/depmori/depmori.html. Accessed 31 December, 2011.

[31] McKenna, Terence, True Hallucinations: Being an Account of the Author’s Extraordinary Adventures in the Devil’s Paradise (San Francisco: Harper Collins), 1994, 69.

[32] Ibid, 75.

[33] Ibid, 71.

[34] Ibid, 88.

[35] Parker, Andrew, In the Blink of an Eye: How Vision Sparked the Big Bang of Evolution (New York: Perseus), 2003, 99.

[36] Theroux, The Secondary Colours, 109.

[37] Ibid, 169.

[38] McKenna, True Hallucinations, 48-49.

[39] Ibid, 61.

[40] Houston, Stephen, et al. Veiled Brightness: A History of Ancient Maya Colour (Austin: University of Texas Press), 2009, 56.

[41] Saunders, Nicholas J. “A Dark Light: Reflections on Obsidian in Mesoamerica.” World Archaeology Vol. 33, No. 2 (Oct., 2001), 232-233.

[42] Ibid, 224.