Why should you and I should be more pretentious? In his soon-to-be released book-length essay, PRETENTIOUSNESS: WHY IT MATTERS (see raves here in the Economist, the Guardian, the Spectator and even Vice), Dan Fox defends it beautifully. “Pretension is permission for the imagination,” he writes. It allows our minds to stretch while we try on new identities and ideas. Without pretentiousness, The Weeklings wouldn’t exist (either in the singular or plural. We each collectively had our own childhood pretensions. How else could we explain our deep love of the essay form now?) Here Dan takes on his own paths from a small village outside Oxford to London and New York through his own roots and longings, leanings and yearnings.

JUNE 4TH, 1989. It’s as good as any place to start. I had turned thirteen in April of that year and was living with my parents in their modest white, semidetached house on the main road out of Wheatley, a village ten miles east of Oxford. Hunkered in a small valley, Wheatley has existed since the Roman occupation of the British Isles, and until the arrival of the car and construction of the a40 motorway, was a staging post on the main road from Oxford to London. Pretty seventeenth-century cottages and pubs sit next to Victorian churches, interwar social housing and new-build homes for London’s expanding commuter belt. It’s called a village, but for a long time it’s been the size of a small market town with its own state primary and secondary schools, an industrial park, a supermarket.

June 4th, 1989. On the opposite side of the street from my parents’ home is a group of houses built in the 1920s by the Wheatley Urban District Council. Growing up, I looked at them every day. Designed in the “Tudorbethan” style, they have brown pebble-dash walls and large black-and-white timbering on the front. Each has a garden big enough for growing fruit and vegetables, and the houses are grouped into semidetached pairs, gently angled so that they face toward each other. Trees and hedgerows surround them. Firemen, school teachers, care workers, juvenile delinquents, cooks, retirees—custodians of the village’s oral history who have lived in Wheatley their entire lives—call them home. For Andy and Christine Andrews, who used to live in the house directly opposite my parents’ and who babysat me as a child, this was the first and only brick house they ever lived in, after years living in a caravan on the edge of the village. Back in 1938, John Betjeman had described these buildings as among the ugliest houses in Britain. Perhaps he loathed them because they aspired to a history they didn’t have, or were symbols of undeserved class mobility. “Private, timber-faced, and gabled villas had been familiar in wealthier Henley and Oxford,” observed my dad, “but now ordinary people had them and on prime sites, not today’s marginal wasteland.” Why did the Tudorbethan pretensions of social housing matter? After all, they were about as authentically Tudor or Elizabethan as any neoclassical or neo-Gothic stately home in Britain was authentically classical or Gothic.

June 4th, 1989. Maybe. I can’t recall the month but 1989 sounds about right. I had borrowed from a school friend a cassette copy of The Velvet Underground & Nico. It didn’t make me particularly original—it’s on the beginners’ curriculum for any budding rock music fan these days—but it made my imagination rapidly telescope from Wheatley to Manhattan. A kid’s idea of New York kindled by Superman and Ghostbusters entered puberty, and I got the hots for CBGBs and Warhol’s studio, The Factory. Not that I understood what those things represented—why, for instance, the album cover had the name “Andy Warhol” written on it in large letters rather than the band name. Then my older brother Mark showed me books of Warhol’s art and photographs of demimonde life at The Factory. Mark had left home a few years previously to train as a nurse in North Wales, but by the end of the 1980s, he changed tack to retrain as an interior designer. In his nursing days he worked at a hospital in Bodelwyddan, on the outskirts of Rhyl, not too far from where my Mum’s side of the family is from, in rural Snowdonia. Rhyl, a small seaside town, was hardly New York or Paris, but Mark had always possessed an acute understanding of how music and fashion could take you to other places, other periods. His tactics had always been chameleon, and his 1980s moved from Two-Tone suits through 1940s demob gear to New Romantic, then— via Style Council soul boy—to Smiths-inspired shades and paisley shirts. Mark was into John Waters’ films, American B-movies, and Evelyn Waugh novels. For his eighteenth birth- day he rented the local Boy Scouts meeting room and threw a 1940s fancy dress party, playing music off old gramophone 78s. But to walk through Wheatley dressed up was to run a gauntlet of suspicion; to be authentically himself, interested in unusual art and fashion in a small town, was an act of physical bravery.

Since the age of sixteen Mark had collected The World of Interiors magazine and had used money saved from a Saturday job at a local jeweler’s shop to hone his eye for small antiques and prints. His bedroom décor was not that of your average teenager: a watercolor by one of the Scottish Faed brothers hung next to a silver mirror printed with a picture of Siouxsie Sioux. Decades before eBay and Etsy, Mark had an eye for a bargain, for being able to find vintage treasures where nobody else was looking. I have a memory of visiting Mark’s nursing digs in mid-1980s Wales during school holidays and being met at the door of his room by a marble bust of Voltaire—accessorized with blue- tinted Victorian sunglasses—and the record Architecture and Morality by Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark playing in the background.

My eldest brother, Karl, had left home when I was very young. He found no stimulation in school, and it alienated him. The Air Cadets in his spare time did much more for him. Like Mark, Karl was an autodidact, but he had different fields of interest. At sixteen, he worked at a local car garage, and then at age seventeen, Karl joined the Royal Navy for four years. After he’d finished his naval stint, he had every traditional and modern sea skill, and a seafarer’s confidence. By that time he had taken a correspondence course in basic aerodynamics and learned how to navigate a boat by the stars. My parents understood he needed to get out of town. They persuaded Karl to save up money and go and see the world. He used his savings to get down to the south of France where he found work as a deckhand on boats in the Mediterranean. Soon he was crewing yachts for film stars and Middle Eastern royals. He eventually became a professional yachtsman—racing and couriering boats across the oceans—and for years Karl lived a life of adventure out of two bags: one held a few t-shirts, a spare pair of jeans, the other a couple of cassette tapes and books. An occasional postcard from the Azores, a phone call from New Zealand, or a glimpse of him on the ITN television evening news winched up a boat mast in a South Atlantic squall during the 1985 Whitbread Round the World Yacht Race were tantalizing signposts to other possible lives. Karl was rarely home during my childhood but the idea of him was colossal.

June 4th, 1989: That year, with the exception of family holidays to Wales, the ten miles that separated Wheatley from Oxford was the farthest I got from home. For some reason, in the pictures Mark had shown me of Warhol & Co., it was the striped t-shirts they all seemed to wear that caught my eye. On Saturday afternoon excursions to nearby Oxford, I’d see twenty-somethings wearing similar striped tees with black jeans, winklepickers, and shades. The look was the vu by way of Thatcher’s UK, filtered through bands such as The Jesus & Mary Chain, The House of Love, Spacemen 3, and Felt. They were just ordinary students, but from the top deck of the number 280 bus, they looked like a part of 1960s New York teleported to 1980s Oxford.

That same year I detected other faint signals in town, although I did not know enough to fully parse their meaning.

Like New York’s Harlem, Oxford had an Apollo Theater. (Mark had seen Kraftwerk play here on their Computer World tour.) Next door to this on George Street was a grotty nightclub called Downtown Manhattan. On Queen Street was a branch of a women’s clothing shop called Chelsea Girl. Local shoegaze heroes Ride had a song called “Chelsea Girl” too. Chelsea Girl was somewhere your mate’s older sister shopped. “Chelsea Girl” was Ride’s engine roar of over- driven guitars in a song about driving up to London. When I later became a student, I learned that Chelsea girls were from West London, uniformly wealthy, blond, and all named Caroline. But I knew that Chelsea girls were also named Nico, Brigid Berlin, Edie Sedgwick, International Velvet, and Ingrid Superstar and hung out with Andy in a seedy hotel in down- town New York City.

Dan Fox (right) with his brothers Karl (left) and Mark (center), Wheatley, c.1985

Artist and graphic designer Peter Saville once described how, living in Manchester in the late 1970s and ’80s, the atmospheres evoked by the European modernist aesthetics he used for his Factory Records designs seemed both a world apart from the grim, post-industrial realities of Northwest England, and also strangely similar. If you were romantic enough and half-closed your eyes, run-down 1970s Manchester could have been 1970s Berlin—the kind of city where existential crises could be had, where daily life was experienced on a battle- field for global ideologies. Saville’s appropriation of European avant-garde imagery was, in his words, about “changing the here and now instead of going somewhere else.” That was something I could relate to, a way of pushing the intensely local up against something too big to grasp. Cities shrink to the scale of neighborhoods, and boroughs are promoted to global capitals. When I eventually began listening to the Bowie records in Mark’s collection, I’d hear the line “I’ve lived all over the world, I’ve left every place” and it made an intuitive kind of sense. At that time it didn’t much matter that my here and now was the names of Cotswold villages, that I’d barely been an hour down the motorway to London, let alone Tokyo or Berlin. Wheatley, Staten Island, Great Milton, Massif Central, Cuddesdon, São Paolo. Those were the conditions of life under pop.

Jon Savage laid out these principles in his liner notes to the band Saint Etienne’s debut long player, Foxbase Alpha, released in 1991:

Down in Camden, London is in your throat. The lowest point in the city, a sink for pollution, noise, destitution. But its here that you find the raw material to make the world the way you hear it. Walking through the congested streets and alleys, you’re assaulted by a myriad of sounds, looks and smells from all over the world, each with its own memory and possibility. How to make sense of this? Go with the flow, find what has been forgotten, put it together in a new way. Today’s hauls are: “Mash Down” by Roots and “Bamba in Dub” by Revolutionaries, a battered single telling you how to convert LSD into decimal currency, a couple of Northern Soul compilations on Kent, overpriced UK psych singles on labels like Camp and Page One. The look is easy, wigs, turtlenecks and corduroys: the rhythms of the moment are playing non-stop in Zoom.

The idea is mental freedom: the transformation of the familiar. Primrose Hill, Staten Island, Gospel Oak, Sao Paolo, Boston Manor, Costa Rica, Arnos Grove, San Clemente, Maida Vale, Studamer: Stay busy, out of phase, in love.

I first read Savage’s manifesto on the back of a copy of Foxbase Alpha in the HMV record shop on Cornmarket Street, Oxford. What was Northern Soul? What and where was Zoom? Where, for that matter, was Camden? I had to know.

But at the time I was attending my local comprehensive, miserably divided along tribal lines into Casuals and Goths. Karl and Mark had been to the same school I was at a decade before, and left with a handful of basic grades and bitter memories of bullying. The campus was, however, unusual for a state school. At one end were functional brick classrooms and halls constructed during the 1970s and ’80s, a set of temporary Portakabins that either for lack of funding or excess of inertia had become permanent classrooms, and a pair of WW II-era hospital huts that the us army had built in the 1940s, repurposed for the art department. At the other end of the grounds was a seventeenth-century manor house with a wooded, moated island and large playing fields. Looking back, it was one of the strangest back- drops for a state education. The school served children from Wheatley, from council estates on the eastern outskirts of Oxford, surrounding farms, and well-to-do commuter-belt villages. I remember, in class aged thirteen, one pupil arrived covered in mud from his mother’s farm and had no time to wash nor spare clothes to wear, while another was talking about where his parents were taking him skiing that half- term. Look one way and you could be on the set of a BBC costume drama. Turn your head and you were in a gritty Ken Loach film. The school’s class hierarchies were palpable but they felt fluid, interchangeable.

The Jennifers, gig ticket, Forest Hill Village Hall, Oxfordshire 1989

Between the ages of twelve and fourteen, I played in a band called The Jennifers. My classmate Gaz had asked me to join. We were precocious, playing cover versions of songs by The Smiths and The Cure, all learned by ear from our older brothers’ record collections. Other, more illicit, influences floated in from the edges. In the late 1980s and into the early ’90s, small illegal raves arrived in the countryside surrounding Wheatley: acid house parties spreading beyond the cities to disused airstrips and fallow fields. You could hear them at night, or cycle past them on a Saturday if it was a weekender that hadn’t been shut down by the police. The raves were occasionally organized by groups of new age travelers who would camp on Shotover Hill, just beyond the village. They were a common sight at that time. On trips to Wales or to Dorset during the school holidays with Mum and Dad, we’d often pass the “peace convoys” on the road, their mud-splattered vans and brightly painted buses being shunted by police from one part of the country to the other. The travelers were the folk devils of the press at that time, their sound systems, with thrillingly shadowy names such as Spiral Tribe, Bedlam, and Mutoid Waste Company, filled the TV and radio news. Teenagers from school would go and score weed from the travelers up on Shotover. It seems almost quaint now, but flyers were distributed across Wheatley warning parents to keep an eye out for perforated sheets of LSD circulating among their children who might mistake them for stickers or stamps. The 1960s teleported into the present again. Time travel wasn’t so unusual for a village steeped in history. Each year, a play about Wheatley was staged. It would be written by the local playwright, involve locals in all the roles, and each time tell a different story about the community and its past. If the acting was hammy or the sets wobbly, it hardly mattered; what mattered was the value the community attached to telling stories about itself; pretending as a way to find commonality.

I was aged fifteen or sixteen when I first started making day trips up to London on my own. Heavily into style magazines such as iD and The Face, along with the British music weeklies, the capital was the most impossibly exciting place I could imagine; a potential life in art or music seemed embedded in every one of the city’s grimy, yellow stock bricks. Figuring out the mechanics of urban subculture was detective work. I could look at The Face and see what t-shirts the kids wore, how they did their hair, but the photograph might not show what shoes or trousers were in fashion: that’s where guesswork came in. Local vernacular styles developed by pretending you knew the whole picture. There was no internet to refer to: those conditions were not necessarily better nor did they carry any more authenticity than today; they were just different. Grunge never caught my interest, and Kurt Cobain’s suicide in 1994 did not hold as much significance for me as it did for others my age. Instead I lost myself in jungle and techno tapes, in music by bands such as Suede, Blur, Ride, Pulp, The Auteurs, Elastica, and other groups then strongly associated with either Oxford or London. It became a task of utmost importance to work out what Northern Soul was. Hours were spent devouring Mark’s record collection at home: Bowie, Japan, B-52s, Kraftwerk, The Cramps, Orchestral Maneouvres in the Dark, Kate Bush, The Smiths, Communards, Thomas Dolby. At my Saturday job in an Oxford bookshop, I would swap compilation tapes of music with Steve, an older colleague who opened my ears to Eno, Can, Throbbing Gristle, Steve Reich, and The Fall. I had another job working as a waiter in a cafe; one colleague was a performer from the Rambert Dance Company convalescing from a back injury, who got me listening to dub music as we opened up each morning.

I was lucky enough to grow up during a period of progressive television programming: BBC and Channel 4 would run seasons devoted to New Hollywood cinema, or the French New Wave. It was late night television where I first saw films by Kenneth Anger and Sally Potter, not in museums or at art-house cinemas. One night while sick at home with the flu in my early teens, I insisted on listening to BBC Radio 3, because I thought the classical music broadcast on that station would be soothing. Instead I heard the dissonant, experimental sounds of John Cage; I was too ill to get out of bed and turn the radio dial, too captivated and yet unnerved by the alien harmonies of his “prepared pianos” to want to tune out. All of this was my raw material for making the world the way I saw and heard it.

By the time I hit seventeen, my friend Gaz, along with The Jennifers’ drummer Danny, had left school to take his chances playing in the band Supergrass. Seeing them perform on the TV show The Word one Friday night only made me further aware that Wheatley was not the place for me.

But a village could be the place for other schemes. In the summer of 1994, a school friend built a small radio transmitter using mail-order parts. That July and August, along with a couple of others who were heavily into Dj-ing, we ran a pirate radio station called Bush FM broadcasting nonstop rave, jungle, and house. The station had a range of one mile, our listeners just the odd friend tuning in on a car radio, but audience reach was not the point. The fun of it, the possibility of even doing it in the first place—that was the point.

Soundtracking as much of my day as I could, music became an agglutinator. Experience and memory clung to it like insects on flypaper. To this day I find it hard to dissociate Bowie from the fogged-up windows in the kitchen at home as Mum cooked dinner, or separate Ride’s music from the way the sun hit my room when I had to get up for school. In turn, atmospheres of place added drama to the music I was collecting. Sat on the Oxford Tube coach as it drove through suburban London along the Westway, the view out of the window snagged on the music that played on my Walkman. Park Royal, Massive Attack, Acton, Pet Shop Boys, White City, Aphex Twin. Place names, Tarmac, and brick glommed onto music like barnacles on a ship.

Photographs and tapes from Bush FM pirate radio station, Wheatley, 1994

Mum and Dad used to insist I get the earliest coach into the city so I could be back home in time for dinner. This meant that some of my earliest memories of being in London as a teenager involved mooching around empty, early morning streets waiting for shops or art museums to open. I learned its atmospherics—the smell of the Tube, growling black cabs— and enjoyed recognizing street names from songs and movies, constructing mental narratives and wiring pop-historical connections of my own. Art, music, clothes, magazines, films: these were my time machines, my teleport devices, and armed with these I knew that one day, London would belong to me. My strategy was mental freedom: the transformation of the familiar. I would eventually live in London for ten years, discovering that most of the interesting people I met there had grown up outside the city, drawn to it by similar promises of a life less ordinary learned through the art, music, and fashion that London disseminated.

“Primrose Hill, Staten Island, Chalk Farm, Massif Central . . .” Wheatley, Oxford, London, New York. Dreaming big in small towns, sweeping sentiment and an eye for detail, it all sounds pleasingly, simplistically, romantic. But doesn’t all that daydreaming imply a snobbery of geography that equates the small town with the small mind and the big city with promises of success and creative self-realization? Even if you get down the motorway from Wheatley to London there’s always that moment when you have to acknowledge that you’re not somewhere even more exciting—Mexico City, say, or Los Angeles—you’re stuck in a bedsit in Rotherhithe. Unless displaced somewhere by war, money, or famine, we like to think of ourselves as having an authentic right to a place. It is other people who are “immigrants,” not us, not our forebears. It’s those people down the street who are gentrifying the neighborhood: we, after all, are sensitive to cultural context and would never dream of eroding what attracted us here in the first place, would we? Surely we’re not pretentious gentrifiers, we just came here because we dreamt of leaving our small town for a life of the mind in the big city, right?

My brother Karl eventually settled overseas. Traveling light became too heavy, a life on land offered new possibilities. Mark stayed in the north and founded his own interior design firm in 1994. His teenage World of Interiors subscription now looks like an act of predestination. I was strongly encouraged by two art teachers—Bridget Downing and Bob Read—to apply to art school. They pushed me toward the Ruskin School of Fine Art, Oxford University’s small studio fine art department. A classist usage of the word “pretentious” might describe a teenage pupil of a state comprehensive school wanting to go and study fine art at Oxford University but it was a pretentious ambition that changed my life forever. There I came into contact with new ideas, people with perspectives new to me. Three years later I moved to London, got a job on an art magazine, started a career as an editor and writer, and ten years after that I found myself living in New York.

At Oxford, another student once put me down by saying, “It must be nice doing your hobby as a degree.” The idea that fine art could be a serious course of study wound him up, presumably because he could not understand how the amore of the amateur could translate into a serious life pursuit. And yet in some sense he would prove to be right: I have no qualification for what I do. I never studied art history or journalism, and I learned to write and to edit on the job. I became a professional art critic by doing it, by feeling my way through. In that sense my career as a “professional” magazine editor and art critic has been along the same amateurist spectrum as any number of other pursuits I’ve followed, making music or art.

With friends from art school I started a record label called Junior Aspirin Records. Together we have made music in bands with absurd names such as Advanced Sportswear, Big Legs, The God in Hackney, Mysterius Horse, Norwegian Lady, and Skill 7 Stamina 12. Music has never made us a penny but it’s taken us across the world, from Eastern Europe to the West Coast of the us. In 2012 we found ourselves performing in front of an audience of three thousand people in Heihe, a small city on the Chinese side of the Amur River, across from Siberia. (It was my second visit to China; my first had been at the end of a six-week journey by container ship from Thamesport, England, to Yangshan Port, near Shanghai. The weeks of isolation at sea, with the small German and Filipino crew for company, gave me a pragmatic perspective on my life in the art world.) We played our “pretentious” experimental music for three hours and at the end, found ourselves signing autographs for the crowd of local teenagers who had invaded the stage. Our music is not popular in any conventional sense, but we are amateurs free of professional constraints and rules governing how we write and play together.

The God in Hackney, live in Heihe, China, 2012

I would never have followed these paths without Mum and Dad’s example and encouragement. Mum comes from a working-class farming family in the mountains of North Wales. She left the farm to study for clerical qualifications and moved around, from Wales to Canada and back again, eventually ending up in Oxford. She had Karl and Mark at a young age and raised them as a single mother for much of their early lives. Mum’s fortitude is legendary in our family. I think of this every time I pass through New York’s Grand Central Station. Returning to Britain from Canada in the late 1960s, she crossed the continent alone with the boys by train. Arriving in New York a day before their ship was due to depart for Southampton, she and my brothers spent the night at Grand Central, unable to afford a place to stay. It was in Oxford that she met Dad. He was brought up in an Irish Catholic family in Rochdale: his mother a nurse, his father a soldier and peacetime primary school headmaster.

Packed off to a spartan religious boarding school in Manchester at a young age, he was eventually sent to the Venerable English College seminary in Rome to train as a priest. There he experienced the tumults of the 1960s through the lens of the Vatican. His understanding of Marxism in communist Italy came from a German Jesuit academic teacher who had been taken at Stalingrad and studied dialectical materialism in a Soviet PoW camp. Dad raised one hundred volunteers to dig out a hospital for the poor in Florence during the 1966 flood, built a road and the foundations of a primary school in rural Greece just as the 1967 colonels’ coup unfolded, and saw the reform revolution of Vatican II first hand. Countless stories from this time filled my childhood: getting into a private papal audience on the pretense of translating; performing Beethoven’s Ode to Joy on bottles filled with water, combs and tissues, car horns, tins, and toilet brushes in the Jesuit university matriculation ceremony. He saw Dorothy Tutin and the Royal Shakespeare Company perform excerpts from Shakespeare in front of the pope and his cardinals, including Wolsey’s remorse scene from Henry VIII—the scarlet of the actors facing down the scarlet of the audience. Once he accidentally knocked through a cellar wall into someone’s basement kitchen in an archaeological hunt below Rome.

He and colleagues were ejected from a pilgrim mountain shrine for questioning the “miracle” by which a portrait of the Virgin hung unattached from the wall.

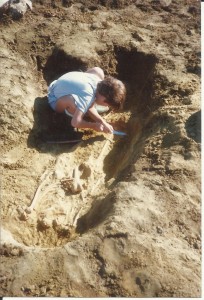

After ordination, he returned to Britain where he worked on a Manchester inner city estate. The church had other plans for him, and eventually dispatched him to Oxford University, where he gained a degree in history and a crisis of faith in Catholicism. He left the clergy around the same time he met Mum and they married after a whirlwind romance, settling in Wheatley. They had little money, and so Dad retrained as a teacher, supplementing the family income with weekends in the Territorial Army. Until his retirement in 2005, he taught vocational studies to disadvantaged teenagers at a comprehensive school in north Oxford, using the summer holidays to write books on topics ranging from Roman numismatics to the English Civil War. He would leap at any excuse for adventure, big or small, often taking me and Mum along for the ride: organizing local archaeological digs on Saxon burial sites, trying to convert a toy cannon into a working experiment in ballistics for his classes at school, salvaging old signs and signals from the disused Wheatley railway station, traveling to the mountains of Northern California to research Irish emigration and the Gold Rush.

Money could be tight but our family was rich in other respects. Mum had been working in Liverpool when American rock’n’roll, Italian-style coffee bars, and cinemas showing foreign films arrived. She understood what culture could do if you could find a way in. It was Mum who took me to London to visit the Tate Gallery, where I first went to a Turner Prize exhibition of contemporary art and first saw work by Richard Hamilton, David Hockney, Roy Lichtenstein. She took me to the theater in Oxford, where we watched Shakespeare, and once caught a production of Bruno Schulz’s Street of Crocodiles by Simon McBurney’s Complicite company. Eastern European surrealism was its look—all wooden furniture and brown 1930s suits, a little Kafka-by-numbers perhaps. It was striking in ways that might appear pat to me today, but at the time I had never seen anything like it. Neither of us knew, beforehand, who Complicite or Schulz was; we went because the poster outside the theater looked good, the tickets were cheap, and the blurb on the flyer made it sound different. Leaving the Oxford Playhouse that evening, we felt exhilarated and entertained. It was an experience we still talk about today.

The author, aged 10, on an archaeological dig, Wheatley, 1986

Mum bought me novels and books on art with her staff discount at the Oxford University Press, where she worked as a production manager. It was Mum who would gamely take my pocket money into the city and buy whatever record I was desperate to get that week. Dad took us everywhere in our imaginations: he brought places alive with his love of archaeology and local history. We rarely went on foreign holidays, but trips to Dorset or Wales would be packed with trips to hidden beaches, standing stones, or castles—experiences that fostered in me a strong emotional connection to the British landscape. Both Mum and Dad had seen the world, they knew that out there was where you had to be, however you got there. All you first had to do was transform the familiar. Without the possibility of transformation, Mum would never have left the farm in Wales, and Dad would still be a priest following what the church would call his “true” vocation— authentic only to institutional rules. My siblings would never have felt enabled to try something different in their lives.

My oddball middle-class upbringing left me understanding pretension as a positive. I associated it with the safe space of the arts, with the adventures of the brothers I loved, with the houses that kind people across the road lived in. With the history books Dad wrote during school holidays and the plays Mum would take me to see and all that they had been through in their lives, which later provided me with encouragement and freedom. I was lucky. I understood pretension as permission for the imagination.

“Mysterious names holding the key to your heart” is how the narrator of Paul Kelly’s day-in-the-life documentary of London, Finisterre, describes the stations on the Tube map. Burnt Oak, Chalk Farm, Angel, Blackfriars. I’ve lived in New York since 2009. My list of stations these days might include Bowery, Canal Street, Atlantic Avenue, Grand Central 42nd Street, and these have a romance of their own. My atmospherics have changed, the polarities have reversed. Britain has taken on a more generalized form, and New York is now mapped in detail: Greenpoint, Manchester, Sunset Park, Birmingham, Harlem, Brighton, SoHo, Glasgow, Long Island City, Colwyn Bay, Lower East Side, Wheatley. A few blocks from my apartment, there’s an Essex Street, a Ludlow Street, a Norfolk Street, and a Suffolk Street. I wonder what these British place names would have conjured for me had I grown up on the Lower East Side rather than in the English countryside? “Go with the flow, find what has been forgotten, put it together in a new way.” Stay busy, out of phase, in love.

From the film ‘Audience Appreciation’ (Dan Fox, 2014). Glenys and John Fox, holding childhood paintings by the author, Wheatley, 2014