THIS MONTH MARKS the four-year anniversary of the killing of Osama bin Laden. In the interim, details about that highly classified mission have leaked out, notably in the tell-all book No Easy Day by SEAL Team Six member Mark Owen, and yet much remains murky. How could the world’s most wanted fugitive have hidden in Pakistan, a U.S. ally, for so many years without the ISI (or the CIA) noticing? Was the relationship between bin Laden and the two spy agencies more complex than commonly believed? What really went on the night of his death? In the last few days, two new pieces of information have complicated the picture.

First, writing in the 21 May 2015 issue of the London Review of Books, but available online prior to that date, the investigative reporter Seymour M. Hersh, in his article “The Killing of Osama bin Laden,” reveals a bombshell about the events of the former al Qaeda head’s assassination. In this account, a retired Pakistani general corroborates what Hersh had learned from American sources, namely:

that bin Laden had been a prisoner of the ISI at the Abbottabad compound since 2006; that [senior Pakistani military leaders] Kayani and Pasha knew of the raid in advance and had made sure that the two helicopters delivering the Seals to Abbottabad could cross Pakistani airspace without triggering any alarms; that the CIA did not learn of bin Laden’s whereabouts by tracking his couriers, as the White House has claimed since May 2011, but from a former senior Pakistani intelligence officer who betrayed the secret in return for much of the $25 million reward offered by the US, and that, while Obama did order the raid and the Seal team did carry it out, many other aspects of the administration’s account were false.

In the Hersh version, Pakistan’s ISI was holding bin Laden prisoner at the compound, waiting for just the right moment to turn him over to the U.S., when one of their operatives exchanged the intel for the reward money. This is a lot easier to swallow than the tale of the mighty ISI not being aware that bin Laden was “hiding in plain sight” in its own backyard.

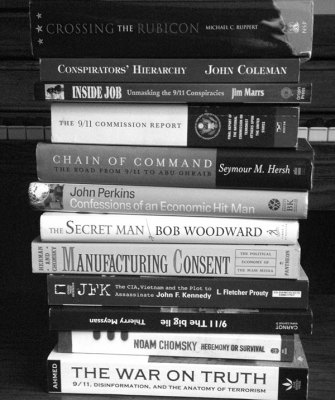

The second revelation, however, only clouds the issue. On 20 May, the Director of National Intelligence released an inventory of “Bin Ladin’s Bookshelf [sic],” a list of all the reading materials (allegedly) found at the compound by SEAL Team Six. Among the religious texts, extremist group screeds, think tank white papers, and al Qaeda media clippings were 39 English-language books. Some of them are scholarly histories by the likes of William Blum, Noam Chomsky, and Bob Woodward. But the lion’s share of his library consisted of what can only be described as conspiracy theory books. The thing is, most of them aren’t even good ones.

John Coleman’s Conspirators’ Hierarchy: The Committee of 300 is impossible to read without concluding that its author suffers from mental illness. I can’t imagine Bloodlines of the Illuminati by Fritz Springmeier is any better. The Eustace Mullens volume Secrets of the Federal Reserve has long been discredited, even by those who believe there is more to the Fed than meets the eye. And Manly Hall’s The Secret Teachings of All Ages reads like a sprawling, crazed rant—not unlike bin Laden’s own meandering diatribes, come to think.

What’s really baffling is all the 9/11 conspiracy books: New Pearl Harbor: Disturbing Questions about the Bush Administration and 9/11 by David Ray Griffin, Michel Chossudovsky’s America’s “War on Terrorism,” Michael Ruppert’s Crossing the Rubicon…why on Earth was bin Laden reading this stuff?

One explanation, and doubtless the one Chossudovsky might propose, is that he wasn’t—that these books were either planted on site or else added to the list later by the CIA, perhaps as a sort of joke.

But let’s assume for a moment that the stories check out: that bin Laden really was holed up in Abbottabad for five years, that the Pakistanis were keeping him there against his will, and that the “bookshelf” released by the Director of National Intelligence was an honest inventory of his personal library. Wherefore the 9/11 conspiracy stuff?

Perhaps these were the only books that he managed to have smuggled in, and his library would have been different had he been able to browse the shelves of his local indie bookseller—although a billionaire who planned a sophisticated terrorist attack from an Afghan cave could probably figure out how to place an Amazon order. It could be that he was such a megalomaniac that he consumed any book that featured him prominently. Or that he was bat-shit insane.

Or the simplest explanation: he was curious.

Plenty of people like to read about conspiracy theory and alternative history. Writers like Alex Jones and David Icke have made it a cottage industry. I take my own guilty pleasure in it—and, full disclosure, I myself own a few of the books on that list.

But I’m an impartial outside observer, and a novelist besides, always looking for a story. Bin Laden reading New Pearl Harbor: Disturbing Questions about the Bush Administration and 9/11 is like Lee Harvey Oswald curling up with Jim Marrs’ Crossfire. Is human curiosity enough to explain why the presumed mastermind of the 9/11 attacks would busy himself reading arguments to the contrary? Why read them? To alleviate his boredom? To mess with our heads? To throw us off the scent? We’ll never know—and never being able to know means, unfortunately, that the conspiracy theories will never go away.