A LAUGHING AMERICAN GI’s foot hovers just above the photographer’s camera. Shot by Shomei Tomatsu, the image is shocking, tightly framed and makes us suspend judgement and deal with ambiguity. The instruction to pause is almost a relief in an exhibition where so much of what is real is hard to believe. It is just one of a number of startling pictures included in the exhibition Everything Was Moving at London’s Barbican gallery. The title of the exhibition alludes to the rapid social changes of the two decades, which resulted in significant innovations in street photography and reportage. Its curators describe it as a “history of photography through the photography of history.” But arguably, the line it tries to draw between the traditions of photojournalism and art photography is blurred.

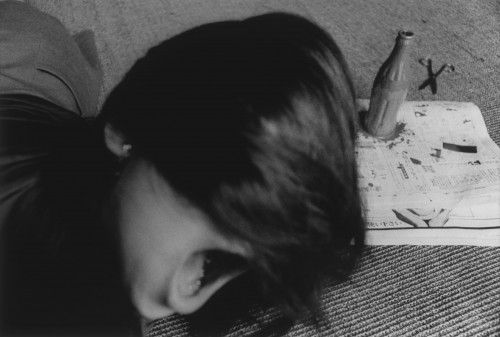

Shomei Tomatsu,Coca-cola, Tokyo, 1969. © Shomei Tomatsu. Courtesy Taka Ishii Gallery and Nagoya City Art Museum

There are big names here – Bruce Davidson, David Greenblatt, Tomatsu, Boris Mikhailov, Graciela Iturbide, Sigmar Polke, Malick Sidibe, Larry Burrows, Raghubir Singh and William Eggleston – as well as lesser-known ones such as Ernest Cole and Li Zhensheng who have only been rediscovered recently. The personal accounts are as fascinating as the documents themselves, not least of all because photographs can be now be shared and distributed within seconds of being taken, the stories behind them lost in translation and dissemination. The work of these twelve photographers takes us through the Vietnam War, the Cultural Revolution, the Civil Rights era, post-atomic bomb and apartheid. Despite the huge scale and the global span, covering India to the US, there is much which unites these artists.

The newly discovered images are especially powerful because of the photographers’ compulsion to shoot and document in genuinely life-threatening situations. Cole, a black South African, concealed his camera inside a paper bag to evade detection when shooting, while Zhengshen buried his negatives in his basement shortly before his arrest by Red Guards. The latter’s work strikingly realigns the past with very recent developments in photography. His red armband and work at the Communist Party-aligned Heilongjiang Daily, gave him otherwise inconceivable access to the daily events of life in the Cultural Revolution. There are panoramas of huge rallies, discreetly taken photographs of individuals publicly shamed for crimes such as being “opportunistic” for resembling Mao Zedong.

Li Zhensheng, Several hundred thousand Red Guards attend a "Learning and Applying Mao Zedong Thought" rally in Red Guard Square (formerly People’s Stadium). Harbin, Heilongjiang province, 13 September 1966. © Li Zhensheng. Courtesy Contact Press Images

But he also loved taking what what we’d now call the “selfie,” carefully posed photographs taken alone at home or in the office that aren’t dissimilar to the ubiquitous self-portrait on Facebook or Flickr. There’s something joyful rather than narcissistic in the public-facing, privately-taken photograph, with the personal pictures forming a counterpoint to the anonymous crowd scenes. The running narrative of the self-portraits seems a way of creating and editing his own history, creating a personal seam inside the panorama of life in the Cultural Revolution.

Being “inside” to get the privilege of photographing is hard-going, requiring a kind of self-destructive bad faith. Cole was only allowed to wield a camera and work for the South African publication Drum by pretending to be mixed race to the authorities. Zhengshen never personally professed allegiance to Mao, but he wore the armband. This is why the inclusion of Sigmar Polke sticks a bit. More famous as a painter, his chemically-splashed and mottled pictures of the Afghan War have a grungy surface which even an Instagram user would eschew. Their yellow coloration and textured surfaces, like old pulpy manuscripts, make them resemble Orientalizing early Victorian photography.

His work exults in the status of an outsider casting light on a backwards world where bears and dogs are pitted against each other for public entertainment. Maybe he’s ironizing Western perceptions of that part of the world, but in this global context, he appears disingenuous. In contrast, the technical virtuosity of photographers such as Cole and Zhengshen seems to be a result of genuine limitations.

Graciela Irbitude’s pictures of Mexico could be snapshots from a fashion shoot, with their dramatically-clothed figures in bone-dry landscapes. Eggleston’s American suburbia is both familiar and distinctively his, the photographic equivalent of Carveresque writing. In his portraiture, the hipsters have light halos and strangely smug expressions, with the backgrounds blurred so the only way to date them is slang on their t-shirts. In contrast, Malick Sidibe’s photographs of Mali music fans in the 1960s give the lie to the idea that black and white pictures bare souls, rather than showing off clothes. These hipsters clutch 12-inch records, standing side-on to show off their perfectly tailored silhouettes. They are beautiful but smack of “good taste” like framed vintage magazine covers or adverts.

Like Eggleston, Shomei Tomatsu’s photographs have influenced successive generations of photographers. The stark black and white of post-war Nagasaki connotes a kind of living death. He is critical of the country’s rapid Americanization, and fascinated by the graphic packaging, the brand names, the exoticism of all the new abundance. Tomatsu has never travelled outside of his native Japan, but his work – more than anyone else’s here – bridges the two traditions of art photography and documentary photo more than any other artist here.

There are strange correspondences to be made between people and situations – the Japanese in post-war Nagasaki give into the confusion, dancing in the rubble; Afrikans blinded to the discontent around them. David Goldblatt’s formal compositions of South African life betray his ease-of-movement in comparison to Cole (he had to time to compose a photo). There are photographs of Afrikaners in dance classes, in Mad Men-esque housewife poses in doorways, beautifully timed images that have a brittle end-of-days quality to them, because we know what exists outside the frame. The scale of the exhibition works because it can include these snatches of seemingly quotidian life, which has such fragile foundations.

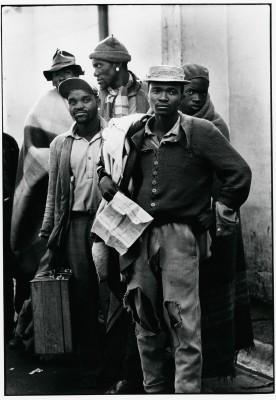

Ernest Cole, (1940 - 1990) Pensive tribesmen, newly recruited to mine labour, awaiting processing and assignment. From House of Bondage Period: 1960-1966 © The Ernest Cole Family Trust Courtesy of the Hasselblad Foundation, Gothenburg, Sweden

Despite the curators’ contention that these artists ushered in an age of artistic respectability for photography, some of the best work is in the documentary photography tradition. What moved me most were the Ernest Cole photographs. There are famous portraits like the small South African child sitting on his haunches in a packed classroom, sweating in the heat, with a conscientious expression on his face. Sometimes there is additional commentary on the photographs, but little text is needed on an image showing a train platform divided between “Europeans” and “Blacks” where one side is empty and the other packed because there are so few trains.

Maybe one of the things about being on the inside is that things don’t appear to be moving. If anything, the frustration of slow change is shown in the number of pictures of delays, crowded platforms, protests, stilled buses, waiting rooms. Bruce Davidson’s imagery of the civil rights era is still viscerally shocking, despite the familiar narrative of struggle. One of the pictures shows a single soldier standing between a black protestor and a line of segregationists. In a drive-by shot of a group of angry white men yelling at Freedom Riders, their faces curl with rage.

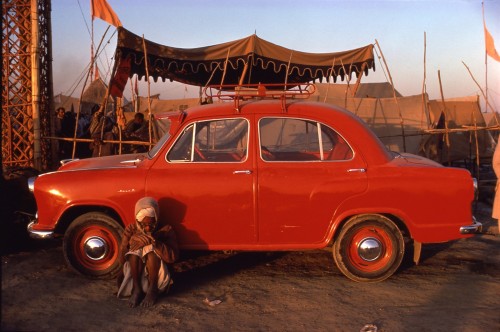

But there are also glimpses of joy later. In Raghubir Singh’s large-scale photographs, we see children swinging up on the tin roofs of Mumbai. The colors are so fleshy, we can almost see dew drying off the leaves. His work’s use of deep colours corresponds with that of his contemporary Eggleston, but he is distinct in capturing collective moments of happiness – which are rarely seen in this exhibition.

Raghubir Singh, (1942-1999) Pilgrim and Ambassador, Prayag, Uttar Pradesh, 1977. © 2012 Succession Raghubir Singh

The size of the show means that some bigger-name photographers act as footnotes, tucked away in smaller rooms. Its scope also might irritate those who want more coherence, a common thread bringing together photographers as aesthetically distinct as Cole and Iturbide. If anything, I thought what the exhibition did best was to reinstate a sense of strangeness, distance, and personal urgency to periods of history and places of which the iconography has become almost hackneyed.