“FUCK IT…”

Are the words scrawled across my older brother Jay’s faded wallet. The same one delivered to me at the small funeral home, along with the rest of his possessions: a half-empty packet of Marlboros and the keys to his Civic. I clutch it in my hands and admire the embossed words. It’s the same wallet he used to take out proudly whenever he’d buy a Coke or pay for gas. Sometimes a cashier would comment on the profane phrasing, and then Jay would smile gleefully like a small boy showing off a prized medal.

A flat tire, last cigarette, being flat-out broke: “Fuck it” was Jay’s go-to motto for anything in life.

“We’ve cleaned him up and applied makeup to the body for viewing,” states the funeral director before talking about the cremation process and tomorrow’s memorial. His words come out jumbled and lethargic. His Georgia-laced accent seems to echo in the large office full of mahogany furniture, as I stare at him wide-eyed and incredulous. My father and younger brother sit beside me, both quiet and alien-like.

We’re the remains of a broken family.

I just flew in from El Salvador the day before and am still reeling from the cocktail of antidepressants, mood stabilizers, and sleeping pills I’ve been surviving on for the past week. The flight had been short and pleasant, except for the burning pit in my stomach. Possible eulogies had sprung to mind, repeating themselves over and over again. None made sense or captured the person that was my brother.

~

As a child, Jay used to swoon over the tiny model cars that lined the basement of the large yellow house we grew up in. As kids, we often joked that the basement was haunted, running up and down the stairs quickly to avoid possession. There was a wide creek we ran to in the backyard lined with unruly trees, pounding on insects and tumbling exhausted onto muddied grass, before stretching out by the water.

We were the only biracial family who lived in our middle-class suburban neighborhood, often producing unsavory reactions from prying neighbors. “I don’t think they like us,” I stammered on several occasions when receiving unwelcome glances.

“Fuck ‘em,” retorted Jay before waving and smiling back.

Later, as a teen, my brother turned the downstairs room into a sanctuary, replete with miniature cars, posters of scantily clad women draped over Ferraris, and the booming sounds of rock that drummed through walls past midnight. At 10, I often crept behind his door, eavesdropping on his phone calls, and guaranteeing his wrath as he forbade my entry into the basement for years.

When I turned 13, he started doodling figures on pale binders on the floor, with dirty laundry, slices of beef jerky, and his collection of CDs scattered alongside him. “Life’s a drag, inhale deep,” was one of his most repeated mottos. “Doesn’t it remind you of me?”, he’d ask after getting a new tattoo on his upper arm at 17. I’d smile and shake my head, “You know Mom and Dad are going to kill you?”

He’d grin and run his hand unabashedly through his frizzy hair.

“Fuck it.”

These unwanted visits later turned into Black Jack sessions and conversations about his defective love life. We became experts at poker, the Cranberries, Sublime, and his profound knowledge of the inner workings of Hondas.

When Jay was 19, we spent hours scouting tiny Cadillacs and Civics at flea markets and toy stores, browsing through aisles lined with Tonkas and Barbies. “Don’t you get bored spending your time putting these together?” I asked. But he’d give me a big toothy smile and sip his Cherry Coke without answering. He often spent hours locked away in the basement, assembling tiny engine pieces and tires. Concentrating on the minuscule paints and details — piecing each part together delicately like a neurosurgeon.

~

Dozens and dozens of these tiny cars stare back at me in the funeral home, their miniature frames lay tucked away in crystal showcases, glimmering inside their wooden displays, as I go through the insides of the “Fuck it” wallet. There, I find his Georgia Driver’s License and Student ID, which he used while studying mechanics at the same Technical Institute I attended before uprooting my life to Central America. I pause for a moment, tracing the outlines of his face with my finger.

Sifting through the credit cards inside, I find a small picture of his fiancée, her golden locks swept off her forehead, revealing deep, probing eyes offset with a coquettish smile, and a number of neatly folded receipts on the wallet’s inside lining. My blurred eyes scan them. The first is a receipt for an engagement ring — $1,000 dollars. I imagine Jay, grinning widely, in a black tuxedo at the altar. His curly hair slicked back into a ponytail. I’d like to reach out and grab those locks now — untangle his unruly hair like I did years before when asked to braid it into thick dreads.

The second is a small slip for a mental health center that has the words “severe depression” and “next appointment” typed onto it. I clear my throat, and the roof of my mouth begins to itch. The mood stabilizer I took an hour ago is now pummeling its way through my system.

My veins almost freeze as I unfold the third: a nearly faded receipt for a handgun.

I read and re-read that word endlessly. Handgun. H.a.n.d.g.u.n.

“Would you like to see him now?” the funeral director asks.

~

It was not uncommon for my brother to come home with eyes glazed over, pupils dilated, and the smell of hash seeping from his dark curls and grease stained clothes. Nor was it unusual to find him sprawled on top of his Honda, smoking a cigarette while staring up at the sky. A million stars watching him as the smoke lifted and swirled above trees before disappearing into the air. Jimi Hendrix guitar strands encircling him like an aura. And then he’d sit up while shaking ashes into the driveway. “Fucking beautiful, isn’t it?”

At other times, my brother was morose and angry; his large boots charging repeatedly down the hall of my room, the sound of the chain worn around his belt rattling after him. I heard him yelling back and forth with my parents, walls being punched in. The sweet stench of rum and coke on his breath as he stormed out the door, not returning home for days at a time.

~

My father and younger brother are with me, standing in the hall of the funeral home. We walk the length of the small parlor, which seems uncharacteristically warm and cold at the same time. It’s February in Georgia and freezing to someone who has spent the last year in the tropics. The air is blowing through the glass doors before we step into the hall outside the “viewing” room. I stare at my shoes that are one size too small and tug relentlessly at my heels.

My mind drifts to my last visit with Jay over a year ago, before moving to El Salvador.

We were at the two-story house he rented with a friend, ordered pizza and watched The Ring while laughing and rewinding the same scene over again of a boy who looked strikingly similar to an ex-boyfriend of mine. We pointed and burst into fits of hysteria, our half-eaten pizza coughed out.

“Hey, I want to show you something,” he motioned excitedly.

I followed him down a long row of stairs into an unfinished basement full of car parts, and a large engine surrounded by greasy tools in the middle of the room. “Meet my baby,” he beamed. His eyes lit up as he went on about the engine model, how he obtained it at a bargain price, and the amount of horsepower it contained. “It just needs some work.”

Jay was studying Automotive Technology at the time and often tried teaching me the lessons he picked up from his classes.

“You’ll need to learn this someday, I’m not always going to be around to do it for you,” he’d state earnestly whenever I showed up for an oil change at the car shop he worked at. I rolled my eyes and laughed as he’d rotate and check the air in my tires.

“Whatever. Where the hell are you gonna go, Scrappy?”

~

I once visited my brother in Florida many summers ago; a welcome break from my parents’ separation — we spent our time visiting movie theaters and beaches, eating spicy Doritos on his white futon, and reminiscing. He often lounged out in the living room, lighting joints and sipping Smirnoff with his roommate. The day before going back home, I snuck into his room and jotted down a quick reminder. A faded note later found tucked between some of his old binders a week after his memorial service.

You are so loved. More than you know.

Never doubt that you have a great heart.

Too good for this world.

~

Jay was my half-brother.

His mother was killed in a car accident on the highway when he was barely two years old, not old enough to remember her. He often kept a small photo of her folded in his wallet. She had the same toothy grin and ample nose with flared nostrils, gentle eyes and slim frame.

“Do you miss her?” I asked sheepishly once, trying to reconcile the missing equation of his impenetrable sadness. We were lying on the trunk of an old Cadillac, staring up at speckled stars and inky blackness while he drew a few puffs from a cigarette.

He flicked a few ashes to the ground and filled his lungs with another batch of smoke — eyes both steady and distant.

“I wish I remembered her enough to miss her.”

~

My father grabs my hand suddenly, his eyes red and swollen, and asks me if I’m ready to see my brother.

As we approach the warm, dim light of the “viewing” room, I imagine that the space smells of formaldehyde and shudder as I picture Jay abandoned on a cold white sheet, instead of sprawled beneath his Civic holding his beloved wrench.

I wonder, Do they need mechanics in heaven?

And what if I had stayed in the US and never moved away? What if I had gone to see him when he asked me to? What if I had called at least once in the past year?

My body is stiff with regret, and it hits me that I’ll never see my brother’s toothy smile again or hear his voice, gruff from years of filling his lungs with smoke. I’ll never hug him again or have an unwanted lesson on car engines. I’ll never get to yell or hang up the phone on him, or have any of the brother-sister fights, at which we excelled over the years.

This will be the last time.

~

At midnight we’d go out for burgers and fries while settling in abandoned parking lots. He drove with one hand on the wheel clenching a whopper, while changing gears with the other. “What do you want to do with your life?” I asked him one night, mayonnaise dripping down his rough goatee. This was a regular practice for us, asking existential questions in the middle of nowhere.

“Going to join NASCAR. You get all the hot women that way.” He smiled and turned up the volume on the stereo until the small hatchback swayed softly with the vibrations. My brother was a fierce driver. Every time I rode with him, I prayed or clutched my seatbelt preparing for a hell ride. He’d speed and change gears like a pro through our suburban streets. The neighbors grimaced every time they heard his Honda revving up. “Here, take a puff, try it,” he’d wave his lighted cigarette toward me and then laugh once I made a soured gesture.

“You know I want you to give that shit up, right?” I said.

He nodded before taking a last bite out of his whopper. “Someday… someday. But not tonight, little sister.”

~

The room is lightly tinged with orange, bathed in calm. The walls, stripped yet incandescent with two upholstered armchairs facing each side. A quick shiver spreads down my spine as I see the supple fabric beneath Jay, outlining his silhouette. A lifeless shell covered in cosmetics to hide the bruising, and tucked neatly away. I notice traces of black grease under Jay’s fingernails, his black and blue hands folded together on his sternum. And there’s a small tattoo on his ring finger, a tiny floral pattern he imprinted with a pen at 16. I place a hand on his and quickly withdraw from its frozen touch. His body had been stored, preserved in a mortuary fridge, absent of light and warmth. My eyes fiercely scan every inch, engraving the images to memory — the slope of his nose and chin, his rough goatee and gentle hands, arms that held me after my own failed overdoses.

By this time tomorrow, I thought, every last tattoo and freckle will be contained inside a brass urn.

Cremated was the word my brother plucked from movies and dead rock stars. “I’d rather burn out, than fade away,” he chimed from Kurt Cobain, as we scarfed popcorn, watching Braveheart late into the night.

~

The windows are blurred at the edges as I walk through the glass doors on the day of the memorial service. My father stands halfway out with the door ajar, his hands shaking and his face hollow, sunken eyes lined by dark circles. We don’t speak.

I secretly blame him. I blame myself.

The bathroom inside the funeral home is strangely warm as my knees collapse onto the floor, black dress floating around my small frame. Mascara smeared on my cheeks. My hands claw at the small rug in front of me, pulling at its brown fibers.

I fucking miss you.

During the service, I tried remembering all of the rehearsed eulogies on the plane ride. But they festered and disappeared as soon as my name was called. Only small fragments of my brother came to mind: his sense of humor and cigarette abuse — curly hair that would afro when humid — a small goatee dripping with mayonnaise and a mechanic’s hands on tiny engine pieces.

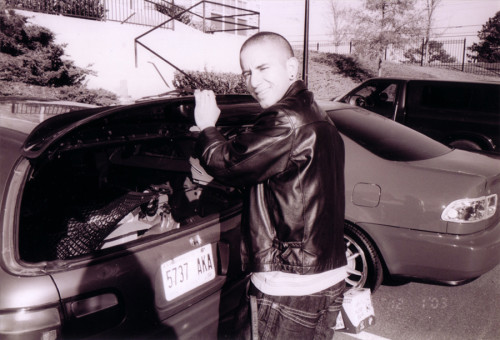

There was a large portrait of Jay with a Mohawk, arms crossed, standing in front of his green hatchback — a look of approval on his face.

I didn’t speak of his character or accomplishments, his dreams or the kind of person others knew him to be. I spoke of miniature cars and mischievous laughter, the doodles on his notepads, and unlikely tattoos. I spoke of his small, graceless habits that would later become my own. I laughed and cried until the emptiness gave way to a kind of fullness.

Fuck it.

I am BLOWN AWAY by this. It hits me right in the gut. Thank you for sharing something so honest and personal, Cindy.

Such a nice thing to say! Thank you Katie, appreciate you. xoxo

Dear Cindy,

This is Swati from IPOG. Got the link to this page from there. Your words touched my heart. I lost my brother last year in December. I didn’t get to see his body. By the time I got to India, it was too late. He was cremated by then. I don’t have any wise words of comfort, as they don’t exist. All I want to say is I feel for you. And that last picture of you both as kids really really tugged at my heart. He looked so sweet…when I see childhood pictures…makes me always think the obvious – when we see happy kids, we seem to assume they will all live up to ripe old age. Normal happy lives. I am looking at his sweet little happy face. No one would have ever thought he would get depressed. I am looking at your face (that little girl is you, right?). So innocent, and looking so adoringly at your brother. Never would you have imagined this. I had never imagined my handsome brother would be disfigured by Cancer one day. I wish I had a magic spell that I could place on every child, “You shall live a long, happy, healthy life, full of love, laughter, abundance, success. Sorrow shall never touch you”.

Much love,

Swati

Swati, your words touch my heart, truly. I’m so sorry for your own loss, it never seems to make a difference the way we lose people, only that they’re gone. I do think that their magic remains in us, in the most brutal, raw, beautiful, and honest way. Sending you much love. xoxo

Cindy, this is powerful, painful, raw, and a testimony I’m sure your brother would be proud of. Thank you so much for digging deep for this.

Grateful for your words, Jordan! Thank you!

Do they need mechanics in Heaven? juxtaposed with details such as the hands (nails) of a mechanic (as a mechanics daughter, I know of what you speak and what the funeral home hid by folding)—-you reach into my ‘readers’ heart and remind me of life, Cindy; its sorrow and pain, things I’ll never get to do again–and then you put ‘the reader’ back together again (a very clever soothing), and thus the reader is changed.

Thank you, Marie, really appreciate your kind comment. I’m honored that the piece resonated with you. xo

Very, very moving.

Happy birthday. Your father was and probably still is a total scumbag. Hope you hold him accountable for being a spoilt child. You strangely seem oblivious to his lousy parenting. What happened is not your fault, only his.

There’s a fine line between, being cathartic and exploitation.

Cindy. I am so very very sorry for your loss. I know its unimagineable. Keep those you still have as close as you can no matter the distance physically and emotionally. It’s important. Even if they aren’t available currently.