(In Part II of Young Adult, Quentin Rowan writes of the tranquility being shattered at an artists’ colony as one writer, a children’s author, has a nervous breakdown.)

HALF AN HOUR later my mother woke me. She told me they were gone. The directors had asked Nancy to leave. I looked around the pale yellow room. My mother with her dark T-shirt and dangling turquoise necklace described how unpleasant the scene had been. All the artists and the directors standing around and Nancy still talking about a fire in the Children’s Barn. A fire that would come, sweep in like a storm, a kind of judgement, against all degrees of the community, not just the old and the decadent and the guilty, for innocence has two sides to it, two faces.

“What about Alice and Kenneth?” I distrusted her story but likewise was beginning to wonder if my pre-dawn adventure had really occurred. I could already feel the memory of it growing thinner.

“They looked sad. But used to it,” my mother said. “As though it had happened before.”

“Or was always happening.”

“Anyway, the two of them took up a kind of football formation and got her into the car. And of course, what we were all thinking as we watched her white face vanish in the rear-view mirror, was how odd it was to see the tables turn.”

“Tables?”

“They were now the adults and she was the child.”

I found myself nodding and wanting to sleep. I wanted to wipe out all recollection of that morning, and my connections to the older children. They had shown me something pure and cool outside the slipstream of ordinary things. Then they left. I could find no way to account for it but to think of fragments coming together, however briefly. I knew my lip was quivering as she ran her hand to and fro through my hair, the way one would a doll’s head, and I knew this was simply what adults did to comfort children. But whatever reassurance it seemed to provide wasn’t enough to change anything with my feelings.

I closed my eyes so my mother would leave me. When she did, it felt like both actions were part of the same motion. She didn’t know. All she could do was reach. Try to reach.

How long could you hold your hand out to another? You had to pull away sometime, let go, before it broke you.

My father left when I was two. Before that we spent summers in Chatham in an old gray house with a pointed roof. The lawn was wet and green and all around were clouds like smudges of winter in the sky. As soon as I could walk, my parents let me run over the grass there from the brim of the trees to the pump-house that clung to the tip of the swelling dunes.

I always dreamed that I would trip and stumble in some overgrowth or mud and fall, so that they would have to come together and help me up. I would hold both of their hands, suspended between them, barely able to reach that far up, as we crossed back towards the house where the light grew brighter.

But there, in the Den at Cummington, in the heart of a forest of willow and birch, my hands were empty and I was alone.

Sinking once more into the swamp of dream-time, that thing my mother said, that the children were now the adults, came crashing back, growing louder and brighter like the revenant trail of some comet. It lit everything with a steady flame and just for an instant, before sleep took me, I could see how those roles, parent and child, father, protector, mother, nurturer, were not roles for people really, but abstractions, life masks, vessels to be filled for a time with a particular energy or heat signature, soul even.

There was something amorphous enough about the roles, that some might be more passive and some more active in filling them. Some might hide within them a kind of latent darkness. Some might even flit from one to another, away from work, away from duty and commitment, away from pain and always towards ease, the lazy vestiges of summer, until these things were all used up.

Then one day that person, that being, that energy – now crushed and fallen – would have to raise its arms and ask for help and hope that some empty hands, a pair of them, might come along to lift them up.

~

Nancy returned several times with officials from the fire department and bigwigs from the Massachusetts’ government. She simply wanted to show them how the Children’s Barn might catch fire.

But the visitations didn’t stop there. She came to us in dreams at the Children’s Barn, spoke with us, poured us milk, asked for more stories from our psychic frontiers, where all was together.

One day my mother was painting a watercolor in the little cemetery next to Vaughan House, near the little monument that marks where Cullen Bryant was born, when Nancy appeared. Like a ghost, she said, who lived on both sides of the wall.

~

Many doubted whether a boy of seventeen could have written a poem like “Thanatopsis.” Richard Henry Dana Sr., associate editor of the North American Review, who published “Thanatopsis” in 1817, questioned its veracity: “No one,” he said, “on this side of the Atlantic, is capable of writing such verses.” The poem was collected in 1821 and Bryant proved to be the first American poet to be taken seriously in Europe, still the Ante-Bellum Southern literary critic Thomas Holly Chivers believed that the “Only thing he ever wrote that may be called poetry is ‘Thanatopsis,’ which he stole line for line from the Spanish. The fact is, that he never did anything but steal – as nothing he ever wrote is original.”

Holly Chivers never went any further with his accusations, but I myself was discovered almost two hundred years later, to be guilty of plagiarism. Like Bryant, I began writing poetry at a young age, but other things, fears and memories, blurred my connection to that part of myself as I grew older. Because I’d based a major portion of my outward identity on being a writer and started to care too deeply about the opinions of others, the situation got complicated, and I found myself stealing.

There was a five minute window of time between a call from my agent and admitting everything to my publisher. I realized I was standing at my fourth-floor window watching the street action below and the early-morning light cross the tenement courtyard further on. I caught myself wondering if I had the energy to open it and climb out and jump. If the sidewalk proved to be a final wall, would it swallow me up into its broken lines or would the breath just leave me as my body broke?

I thought of “Thanatopsis.” It appeared in my head after years as a memory, and I finally understood its gentle appeal. The comfort, even from my darkest wishes, of hoping the “Earth, that nourished thee, shall claim/Thy growth, to be resolved to earth again… To mix forever with the elements;/To be a brother to the insensible rock/All in one mighty sepulchre…”

With all the deep lines I’d made between myself and the truth weakening, still looking out the window, but with no more need to struggle or to run, I could remember at last crossing that boundary with Alice and Kenneth, unfocused and invisible, beyond the Rivulet and into the birthplace of “Thanatopsis,” or the sight of death.

Out of the animal rawness of imagining my skin, the structure of my pelvis, my skull and spine stretching out along the pavement below, I could see that our brief moment of refuge, there in the woods, a kind of last childhood sleep, had stayed with me.

~

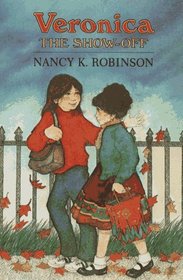

The first Veronica book, Veronica the Show-Off, appeared four days before my eighth birthday in October of 1984. Nancy died of cancer ten years later. She was fifty-one.

~

William Cullen Bryant returned to Cummington when he was seventy-two and bought back his childhood home. A rigid white and brown Dutch Colonial, he lived there until his death at age eighty-four.

~

I’ll be honest with you. I’m having trouble finding an ending here. The path I’m on no longer leads to silky raspberry thickets, nor backwards to that indigo morning on the other side of the Rivulet, but at least it is clear.

Sometimes I am constrained by problems, taken off on side-trips mostly to do with the way my mind works, short-sightedness, illusions, inability to see the whole.

I wonder if it is any use to say I’m trying? I am writing about things like death and memory and the succession of youth, but I’m afraid, because of some preoccupation with my own trajectory, in the most limited way. It’s up to you to ignore this, to disagree, or to listen. But all I have are memories, to make a kind of sketch. And even those converge at some point with the future. The future too, will have to form a link with death at some point, both the subject and the substance.

God, it all sounds so dark and heavy. But when I did, at last, open my fourth floor window and consider jumping, it wasn’t into some perpetual blackness that I looked but something more like a process. A revealing. The real motion, were I to take it, would not be a fall from life to death, but to a place unfolding beyond death.

~

Carole Maso went on to write several other novels including Ghost Dance and Ava. She has been a professor at Brown since 1995.

~

My mother is still a painter. She struggles with carpal tunnel and can only work a few hours a day.

She prefers to work in the afternoon now, when light floods the south window of her studio.

~

Last week I found a copy of Veronica the Show-off. It was hiding underneath a pile of leaflets and bundles of other children’s books at a library sale in the country town where I live. I studied the illustration on the cover for a moment, but the little girl there looked nothing like Nancy. I opened to a random page and read:

“Veronica shook her head very hard. She didn’t want to think about friends. All they do is go away and leave you anyway, she told herself. Everybody does that.”

~

I paid a dollar or two for the book and wandered back to my little gingerbread house. It sits along a brook I can sometimes hear coursing through the night, whispering to me like a prayer, a daydream with the soft and easy sway of summer.

It wasn’t until I reached the front door that I realized I’d been pressing the book to my heart, knowing it – after all these years of falling – for a friend.