WHAT WOULD IT REALLY take to create a real life superhero?

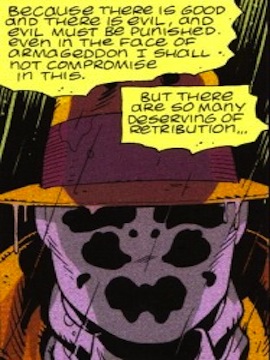

I’m not asking in terms of money or esoteric abilities (although those things are indeed benchmarks of the trade). Such additions are of relative consequence in the world of comic lore when you consider Batman, Judge Dredd, or—with exception to Dr. Manhattan—the entire cast of The Watchmen. Rather, I’m talking about the severity and degree of conviction it would take to mash a human being’s identity into that of an effective vigilante, one that wouldn’t look anything less than ridiculous in an identity-grade costume, and that would be able to enact substantial change upon planet Earth, with its multitude of disturbances. Imagine a single human being, successfully combating raving bomb-makers; swindlers; fanatics; rapists; demagogues; the world’s sea of angry dispossessed; violent political factions; wide-eyed despots à la Bashar al-Assad who slaughter with indiscriminate furor; global warming; tidal rifts; tsunamis; and nuclear disaster, all while heeding the horrifying complexities of cause and effect.

Sounds like an easy feat, right?

The answer is basically the basis for my first novel, League of Somebodies, due out tomorrow from Dark Coast Press. I’m hardly the first author to grapple with the idea of attempting to test the superhero fantasy against the backdrop of everyday life. Alan Moore, Grant Morrison, Frank Miller, Mark Miller, and others have asked these difficult questions of the genre. If you’re a fantasist to any degree, and grew up with a penchant for escapism, then you know what it means to find solace in alter egos, to follow the evolution of your favorite heroes as if they exist in flesh and blood. You also then know what it’s like to feel trapped inside reality, with its biological constraints and its daily lack of change, where acts of heroism and villainy occur often in isolation.

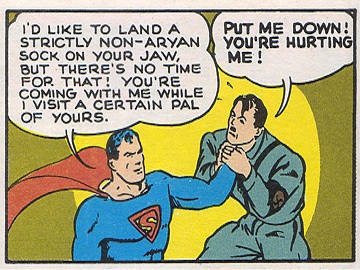

The stuff of comic books is essentially a raw, undiluted breed of native magical realism, American in origin and as ingrained in our culture as jazz, baseball, or the WWE. Joe Schuster and Jerry Siegel pioneered the genre with their Socialist imaginings of the perfect Everyman, an enemy of wifebeaters and crooked politicians, endowed with the public persona of a clumsy nebbish that lent a new dimension to identity. Such is the fruit of their 1930s creation, Superman, who eventually, like all superheroes, became property of comic’s culture, subject to basic rules to be enforced by generations of fans, regarded with both sacrosanctity and venom. Those unstudied don’t know that Kryptonite itself wasn’t even a part of the original design for the Man of Tomorrow, dreamed up instead—as pointed out by Grant Morrison in Supergods: What Masked Vigilantes, Miraculous Mutants, and a Sun God from Smallville Can Teach Us About Being Human—after the hero’s sale for a miserable sum before the franchise truly exploded. Siegel and Schuster, two youths born from Jewish immigrant families that fed Kal-El’s journey of exile, breathed life into an unusual genre somewhere between prose and cinema that gave us news ways in which to sublimate desires and combat societal menace. Nazism, WWII, Civil Rights, The Cold War, you name it—comics have been there. Even during a brief and torturous period in the Fifties when the moral noose was tightened around their very existence to keep them from corrupting America’s youth, they can be thought of as a map for societal exorcism. Solar flares from the collective unconscious.

My origin story, in comparison to that of the comic, is characteristically undramatic: I grew up across the street from an elementary school and a small electrical plant from which, as a child, I imagined invisible emissions forming a static dome over our mustard yellow house in suburban Colorado. My parents, Jewish transplants from economically disparate East Coast backgrounds, seemed not to be bothered by its presence as much as that of their neighbors, who operated at an overwhelming Western cow-town pace compared to what they were used to in Massachusetts. The electrical plant—heralded distantly by three massive satellite dishes a few prairie miles out, lying dormant like the inactive hands of giant robots jutting from the ground—was a mess of cables, barbed wire, and WARNING signs. Its crude structure was a blatant stain of industry that my father had ignored when carving out his idyllic pie-slice of suburb for a modest price. And that’s what I remember from my days as a child. The grey, spiny fray of wires in our green Arapahoe County wilderness and the wiles of the man who walked the halls of our home, setting rules like booby traps. The man in spandex shorts, dripping tanning grease and a fevered desire to see his family succeed.

Like all children raised by a fuming patriarch near a potentially radioactive power field, I suppose, comic books became a natural obsession of mine. The heroes of my youth would come to populate the pages of DC and Marvel rather then Sport’s Illustrated, much to my father’s chagrin (he named me after Patriot’s fullback Sam “Bam” Cunningham, for fuck’s sake, not Sam Wilson, detective alter ego of Marvel’s The Falcon). What enthralled me, you see, was what inhabited the fenced-off world behind the WARNING signs, the dim and clandestine secrets of scientific function I was unable to comprehend with my mind alone. While my mother would complain about how ugly the structure was, how the neighborhood should petition it be removed, my father would dismiss her cares, mostly because he was fenced off territory himself, a balding business owner interring his family inside a bunker from which to carry out his one-man war against the universe. Looking to the muscle-bulged forms crossing the pages of 90’s comics, the heroes and villains who warred back and forth over objects of power or civil significance from the Cosmic Cube to Gotham City, I practically pictured my father in every scenario, some wayward antihero battling for the mastery of his misery, taking to task life’s daily letdowns, and, by default, the very cosmic dust that created him.

Okay, I couldn’t have possibly articulated such sentiments growing up in any meaningful way. But I do now believe that the bulk of my fascination with comic books stems from profound confusion over what it means to be male. From what I have to work off of, man’s desire to succeed, to mark his territory on the rock of Earth with a steady stream of psychic urine, stems from a deep fear of nonexistence, and more poignantly, irrelevance. The male ego, in its enduring fragility, is subject to embellishment precisely because it is so subject to destruction. My novel, League of Somebodies, consequently tells the story of a man who tries to make his son (the main character, Lenard Sikophsky) into a genuine superhero for what we can only imagine are selfish reasons. The way the father does this is by sneaking measured amounts of a plutonium compound into his daily meals, poisoning him, unrepentantly, in the name of future greatness. It’s a story of madness and absurdity based upon a genuine hatred of reality, loathing not the world we imagine but the world we know exists. A notion I admit falling prey to as well, and which most wrestle with on a consistent basis.

Since I can remember, most of my daydreams centered around dropping in to save the day, usually against bullies, narcissists, and opportunists, knocking them all into a stupor with buzzing fists of fury. Chastised throughout childhood and always dodging social doom, I fantasized about powerful rebirths. I hated being invisible, though that’s exactly what I was: invisible, relatively unattractive, not at all like any given male member of the X-Men, even Beast. I also had a deep fear of masculinity. Sexuality notwithstanding, I found it overbearing and constantly unsatisfied, like the gullet of some ancient god. This is because I grew up with a man for whom no measure of success was quite enough. If he took a solid step forward, he cursed his, and his family’s, lack of foresight to have leaped. He saw himself in the mirror as aging, imperfect, undeserving of happiness. He once tore a man from a car and threatened to “Rip off his neck and shit down his throat” because he had cut him off in traffic. I was there to see it. People stopped to roll down their windows and stare. This was how my father viewed masculinity: as the shit someone forced down your throat. As the disappointment and hardship of daily living that festered and grew and exploded in primal bursts of rage.

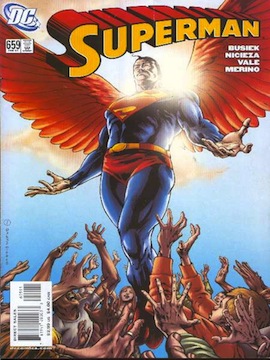

The masculinity in comics was different from what I observed at home. It didn’t involve toughening up or outmatching your neighbors. It was deliberative, and, if imperfect, fraught with responsibility. In a sense, the frightfully masculine muscle-bound superhero suffered from a deeper knowledge of his own fragility then my own father would ever admit. The superhero perceived the world as it was: a place rife with darkness and decay. He ran on the steam of his eternity in order to rectify its wrongs. In comic books, masculinity was not as fearful of being wiped from the face of the earth. The ego was everlasting in the imagination. The characters themselves? Well, they were immortal. This is speaking, of course, in a general sense, being that there have also been points in comic’s history where heroes have fallen hard for misogynistic clichés, stupidity, insecurity, and, yes, death. But the unconscious want for male ego longevity can be found in the pages of most Superman comics. If Superman dies, as evidenced in the The Death and Return of Superman storyline from 1992-1993, he is soon resurrected. Perhaps by the same writer, perhaps by another. Something similar happened recently to Batman following Infinite Crisis. In this way, heroes like the Man of Steel occupy a spiritual dimension. They are the creatures no man can be yet every man wishes he were. They are modern patriarchs in the biblical sense. The meek look to them for rule of law.

The state of women in the comic’s world, however, is still fairly unsettling. This is also a theme of League of Somebodies, the seeming compulsion to marginalize the feminine in order to fully explore male identity. The eventual wife of the main character in my novel is bound to him by contract, and although she has powers and intelligence of her own, she’s often reduced to sadism by her husband’s aloof need to live up to his father’s expectations. I won’t give too much away as to her eventual fate, but in the process of hero-making in any tradition, whether directly religious or epic in nature, women have often been shoved to the side, acting as a secretary to power. Such dynamics can be found between Superman and Lois Lane, when the Son of Krypton plays a game of cat and mouse with Lane’s sanity, withholding identity for righteousness’s sake, but not without a dose of wicked self-satisfaction. And Lois, in a surreal test of Superman’s insecurities, has threatened to leave him behind. Classic comic book superheroes are vanguards against male insecurity, and subsequently protect themselves against the feminine, sometimes to the point of Greco-Roman homoeroticism. This is especially true in the case of Batman and his various sidekicks, which often seem to eschew female love interests in favor of tights-bound adventure.

If anything, I don’t write about the male-charged comic sphere for the purpose of ridicule. All art forms and genres are absurd, especially when taken too seriously. If anything, the comic tradition is a more dioramic method of evincing societal deconstruction than what antiquity has offered up in ancient texts. Comics are a vaccine against reality. A method for processing some of life’s greater dilemmas safely, elegantly, and meaningfully. Comic writers are myth-makers, and comic artists, the light behind illuminated manuscripts. But still, there will always be an element of phallic thrust to the comic world. Something to make boys feel adequate in their own skins. Perhaps a similar phenomenon will extend to women as well (it already has, in many ways, though there’s much work to be done), if the demand continues to be strong.

Here’s a passage from my book that I believe sums up what it was we search for in heroism, from the vantage of the main character:

Normal. This was a word Lenard thought about often. Normal was something everybody searched for, but some found easier than others. It was a lie the whole world tried to hide behind. Strange, however; strange was a staple. Everybody understood strange, and went through limitless measures to disguise it.

I can only hope that, in a similar fashion, League of Somebodies does not disguise, but instead champions the strange, hidden wonder in all of us. I can only hope that it makes us probe what lies behind the heroic aspirations in all of us. For this is a part of what drives us on this planet. What keeps us searching for the secret identities behind our many masks.