THE BEGINNING: It was 3 a.m. I’d been lying awake for some time and I switched on the lamp in the hope it might be morning – proper morning, when the birds would be singing and commuters rising and trains beginning their trundle from Parbold to Manchester, where I was due to meet up with my literary deity. I had spent the evening before attending a talk by Will Self. He’d been interviewed by broadcaster Dave Haslam, made scathing jokes about Britain’s disgraced TV presenter, Jimmy Savile and read from his Booker-nominated Umbrella. Afterwards, I joined the end of a long, long, long queue of fans eager to get their copies signed. It was the first time I’d ever come face to face with Mr S. I’d joked in an interview with The Observer a few months back that if it ever did happen, it would feel like “a Christian coming face to face with God.” In the flesh, he certainly had a sharp stare. However, he did not yank out a pair of scales and weigh my sins in one and good deeds in the other, but signed my proof with a flourish and made arrangements for us to meet for lunch in Manchester the next day. And now I was staring at the shadows on the ceiling and thinking of those lines from Sylvia Plath’s Insomniac that often trouble me when sleep plays its game of hide and seek – Under the eyes of the stars and the moon’s rictus / He suffers his desert pillow, sleeplessness / Stretching its fine, irritating sand in all directions.

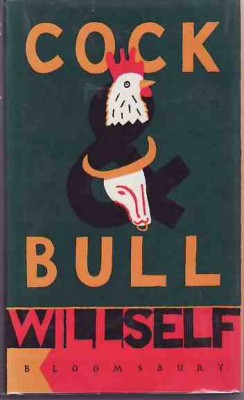

Tonight’s insomnia, however, was a little different from my usual experiences of waking at three and fizzing with a new idea for a book is in progress. It was the 15th October 2012, and roughly twelve years earlier, I’d bought my first ever Will Self novel, Cock & Bull, a Kafkaesque tale of gender transmogrifications where a man grows a vagina behind his knee and a woman develops a penis. I was so impressed by it that, there and then, I decided to write the literary equivalent of Being John Malkovich, only with Self as the center of fascination. A decade later, I got a deal for the book and it was published as The Quiddity of Will Self. When I’d first approached Self with some sample chapters in 2009, I’d been nervous that he might threaten to sue me or hire out a hit man. But his reply – typed on his infamous Olivetti – was one of suspicious support. He told me he had read my work with “amusement and enjoyment” and concurred that I was free to write about him as I wished, declaring “I just want to be misunderstood.” He made it clear, however, that he was unwilling to embroider the cover with a quote. But, when the book began to garner good reviews and we exchanged a few more emails, he seemed to thaw and became receptive to meeting up.

Within The Quiddity of Will Self is an organization called the WSC, a coterie of superficial obsessives who worship Will Self as though he was their deity. The relationship between art and religion has fascinated me for a long time. Art once drew its inspiration from religion, lovingly rendering images of Angels and Saints on wood panel, canvas, church walls and ceilings – even glass (stained, of course). Now art has become a substitute for religion. Religious inquiry, the urge to understand what it is to be human and our relationship with the world around us, and to define what is Truth, has manifested in different guises in different cultures throughout the ages. During the last hundred years, our interest in the supernatural, the mysterious, the irrational, ridiculed and repressed with the dominance of Science and rationalism, has been displaced into the Arts. During the 1960s, as church attendance began to fall significantly, a new generation worshipped – with a feverish, Bacchanalian hysteria –the Beatles and indeed made them bigger than Jesus. Star Wars, with its philosophies largely borrowed from Joseph Campbell and the Vedas, spawned the Jedi religion. Readers have queued for hours through the night for the new Harry Potter or Murakami with the zeal that once accompanied the birth of a boy in a stable, whilst empty churches have been converted into shopping malls and pederast priests have been vilified. But while Christianity is no longer in vogue, its structures remain. Take the example of the desire to confess a sin. Priests have been replaced by psychiatrists. A patient might lie on a couch and confess to masturbating while fantasizing about murdering her mother – but instead of being told to recite Hail Marys, she might be given prescription drugs. The desire to slip behind a curtain and whisper secrets through a grille or lie on a couch and confess comes from the same urge – to find a parental figure who will dispense judgement, play the moral guide, give affirmation to the question am I normal?

In recent times, the urge to confess has been played out on reality TV, for back when Big Brother was a fresh and surprising social experiment, one of its most striking motifs was the place where contestants came to spill their emotional innards. It was a tiny little room, about the size and shape of a confession box, and contestants would share their secrets, asking the public to judge them, the newspapers to analyze them. Even when it did escalate into a Panopticon of freaks and caricatures, even then it was inviting us, the audience, to play the part of the priest/psychiatrist – though the producers assumed we were a collective priest/psychiatrist with a ludicrously short attention span who got bored quickly with standard quirks, and it self consciously paraded a more and more colorful discombobulation of lunatics, in order to elicit more and more extreme judgements. Perhaps the act of confession was less a pursuit of fame, as everyone claimed, but a simple desire to be judged.

History does not repeat but it does rhyme. We recycle the same old plots but we give them different covers and brands. The philosopher John N. Gray argues, for example, that humanism – though seemingly a reaction to Christianity – is, at its heart, a daguerreotype of certain traditional belief systems, such as the idea that humans have a special place in the cosmos and that our history is one of progress. Indeed, I discovered John Gray via Will Self. (He championed Gray’s famously incendiary work, Straw Dogs, and now they regularly do talks together). In one of his later words, Heresies, Gray explores how our religious impulses are as universal and deeply rooted as the desire to mate, eat and sleep; hence, when it is repressed, it leads to perversions. Marxism is an apparently secular system of thought but ultimately still offers the same message as Christianity, promising a socialist utopia on earth following revolution rather than a party in heaven after death. The WSC, therefore, was a self-conscious perversion, a post-modern parody, and yet whilst in my heart, I did not worship Self, I did hold him in higher regard than any other author in the country. Hence, the question of what sort of narrative was going to be played out in our lunch made me nervous.

Just before I set off, I’d glanced at one of my many novels-in-progress that died at a typical page sixty. (I’m very good at openings, but middles and endings are more of a challenge). The novel began with an author winning a competition to interview his favorite author, Augustus Fate, a recluse who hasn’t interacted with the public for seven years. I read the passage I’d written a year back –

Augustus Fate wanted to talk and me to listen; he wanted to be the guru and I his disciple. I felt a sense of disappointment gray over me. We seek out our idols not for themselves, but in the hope that they, with their rarefied consciousness, will elevate us to their level, burrow into our souls and see something special in us. They, however, need confirmation that they are worthy of worship. That was why meeting an idol invariably involves an inevitable crash, as the concrete splats into grey shit around their pedestal.

Now I wondered if I’d been scribbling my own future, if my life was about to mirror my art. How would it feel to discover his Human side, to encounter the Spirit made Flesh?

THE MIDDLE:

We had agreed to meet outside the lobby of the Hilton at midday. We said hi and then for about five minutes said nothing. I was paralyzed by shyness, and I was also busy leading Self to a really dreadful restaurant. Given that he was a restaurant critic, this felt particularly sacrilegious – but for some reason all the local restaurants hadn’t yet opened and we didn’t have much time and I took him to a place that might have been Spanish but might have been Turkish; the lurid yellow menu was less of an ill-conceived fusion between the two than a gastronomic multicultural identity crisis.

“I don’t do food,” Will said. He’d eaten a big breakfast and was battling the recent development of certain food allergies, so he ordered Earl Grey tea and I ordered soup and fries. The soup appeared – I tried to work out what kind of vegetable could be that yellow to have yielded such a broth. The fries were half-cooked.

He asked me how my new book was going. I said that it wasn’t going too well.

I explained that I felt self conscious. I hadn’t ever really expected to get Quiddity published and I’d never been widely reviewed before; I felt I’d lost my creative innocence, that a Fall had taken place, that I sat before my computer with too much awareness, too much knowledge.

Self looked scathing.

He advised me that I ought to just get myself together and get on with it. His first novel, The Quantity Theory of Insanity, had made him the golden boy of the literary scene when it came out in ‘92, winning the Geoffrey Memorial Faber Prize and plaudits from Amis and Doris Lessing. But the publication of Cock and Bull was a different matter – Self related how since then, “There’s been a deep ambivalence about my work – up until the publication of Umbrella, that is.” He shrugged and said he’d never felt self conscious, had always been able to separate his public persona from the private man, the writer who sat down before his Olivetti and typed.

It was a good pep talk. Then he said some things about publishers that made me laugh but would be unfair to repeat here. He gave me advice on the title of my present work in progress, The Bankenstein of London Fields, which he told me to just shorten to Bankenstein. It turned out Self was a bit of a Title Maestro, for he’d thought up titles for a number of friends. He obviously like the short and sharp, for his new book-in-progress was another one-worder – it was going to be called Shark.

~

Why do writers make good deities? Well, the mission statement from the WSC explains thus:

“We have no true spiritual masters in current Western society – our priests are pedophiles, our politicians are celebrities, our celebrities are earthworms. Who can fill this spiritual vacuum? The answer can only lie with writers. Fiction can illustrate greater truths than non-fiction; the enduring appeal of 1984 tells us more about the dangers of an authoritarian society than any history textbook. A writer can teach us about life, morals and how to construct a better sentence. Hence, the greatest writers are worthy of worship.”

They also create good narratives, and the construction of a narrative is an inherently religious act. It creates order out of chaos, it censors the dark and the inconvenient, it makes sense of the mess of life. The ultimate narrative is the obituary – shaping life into a beginning, middle, end, and rewriting it as a story of progress, a Hegelian narrative where each key plot point in one’s personal history must unfold neatly and logically from the next. Obituaries are not just written for the dead. They are our novels-in-progress. We write them all the time, internally, updating them a little bit each day, looking back at an incident and considering, Well, if I hadn’t sent that email on Tuesday, I wouldn’t have met X at the bus-stop and I wouldn’t have married him and I wouldn’t have ended up having sex with his father and therefore that email was the start of it all, and the more years we live on Earth, the more early years are squeezed into small chapters, and the more we are aware that the end is in sight and surely it can’t go on being this boring, there has to be a plot twist sooner or later.

I once attended a film seminar run by Hollywood supremo Robert McKee and one remark he made lingers to this day (I paraphrase him) “The narrative that centers on one protagonist on a journey works because it mirrors the set up of the human mind and the way we view our lives, as center of our universes, casting our crush as the love interest, the guy who thwarts us as the antagonist, our boss the mentor, seeing the conflicts we face as battles on the way to an achievable goal.” There must be something in this, for McKee’s course has given birth to countless Oscar winners. But I’m sure it’s no coincidence that the popularity of this theory coincided with a Me-Me culture in Western narratives in general, and hence our narratives had to narrow from say, the big sweeping epics of Dickens and Eliot, shrunk down to a narrative that favors one key character. Yes, we still like our occasional epics now (Zadie Smith’s White Teeth, John Lanchester’s Capital) but that one-narrator-telling-the-narrative novel is still the favored formula of popular fiction.

Sweeping narratives don’t impress Self either, mind you. Self’s literary deity is the late J.G.Ballard, and Self has described how Ballard’s modernism has influenced him:

“…he united his own modernist sensibilities with what he termed ‘the death of affect,’ a wholesale loss of feeling occasioned by the impact of the atomic bombs that ended the Second World War, and then irradiated through the emergent mass communications technologies of the post-war period – in particular TV. It was this, Ballard wrote, that made it impossible any more to suspend disbelief in those omniscient and invisible narrators of naturalistic fictions, whose tendency to play god with their characters had surely always been a function of their own status as personations of God.”

Umbrella was Self’s sticking his middle finger up at the classical narrative, and his manifesto on modernism had a political element to it too, given that these days, politicians have also become increasingly fond of feeding us bullshit via narratives rather than statistics. As Self has pointed out, the novel has fluctuated between different forms over the last few centuries, but in the end, has turned its back on Modernism and opted for the safety of “’jolly good reads’ with a beginning, a middle and an end – including almost mandatory redemption for a previously morally vacillating protagonist – is the very stuff of books, just as it’s the stuff of life on this right, tight little island.” (Self, writing for The Guardian). Even the God of Christianity is keen on his classical narrative structure, given that the Bible begins with Genesis and ends on Revelations. Self, then is a more subversive and timely deity, for The Book of Dave, in which the rants of a taxi driver become the foundation for a religion centuries on, is much more worthy of serious attention and has been deemed the holy book of the WSC.

In The Quiddity of Will Self, Self is awarded the Booker for a novel called Drug Lime. In my fiction of his fiction, Drug Lime is his last piece of work: a novel about a drug that becomes addicted to a human being, inspired by a saying of William Burroughs that smack is the only commodity you don’t have to sell to people; you sell people to it. The timing of our lunch was prescient, for that afternoon Will was due to head south again to join a panel of novelists in conversation at the South Bank, London. They had all been short-listed for the Booker; tomorrow their fate would be decided. Wikipedia – with its usual predilection for erroneous facts – states that Umbrella was the first time that Self had been nominated for the Booker. In fact, he was nominated a decade earlier, for Dorian, but that was on the long-list. It had been a considerable time, then, since he had been in the running and here was a real buzz building that Self was going to win. The London bookies were now listing him as their favorite. But during our lunch, I probably came across as more excited about the possibility of his winning than he was; he was rather blasé. Having spent much of his career as a literary outsider, he seemed ambivalent about receiving a prize from the literary establishment.

THE ENDING:

In The Quiddity of Will Self, Will’s death occurs in 2045. His body is preserved in formaldehyde and sold for $6 million to a philanthropist in Nashville who puts it on display in a tower block for the public to view. Due to financial difficulties, the collector ends up carving up parts of his body and selling them off. One hand ends up floating about in Egypt; his liver/one eye goes to an elderly aristocrat living in London’s Berkeley Square. But Self undergoes a Resurrection in the novel, for one of his eyes retains Will’s consciousness and communicates through blinks. The aristocrat keeps him alive and regularly plays him Radio 4; Self is less than impressed.

The WSC believes that, on dying, we all move to another part of London – specifically Dalston, a hipster-ish but gritty place in North East London, in keeping with Self’s How the Dead Live. On the day that our deity dies, we plan to enact a suicide pact. The WSC, in short, is both sincere and satirical, a genuine worship of our greatest living novelist and a mad cult that parodies the absurdities of religion. If it sounds as though I am sneering at Christianity and organized religion, then let me assert that I am not a militant atheist. To parody through example, however, seemed a more potent and imaginative way to make my point than Richard Darwin’s blunt and tedious attacks. Besides, I am an agnostic rather than a hardcore atheist: I have sat in churches and ashrams and enjoyed that feeling of peace which passeth all understanding, a sense that there is a divine force that sings with sweetness and love. But there can be no doubt that religion brings out of the worst in us, in its superstitions, its rituals and its potential to blinker the minds, so that we are locked in cages of cognitive dissonance, in ego matches of My God is Bigger Than Your God.

When the front of Will’s Stockwell family home dramatically crumbled last year, depositing hunks of rubble into his front garden, I saw a comment on one of the news reports crying, Isn’t this hilarious – Self is a militant atheist and his house has been knocked down by an Act of God!! But if you look a little deeper, Self doesn’t fit into this category either. On a youtube video, he is asked whether he ever prays. He says yes. He is asked if he believes in something higher. He says yes. His advice is to “allow yourself the luxury of doubt,” because whilst he doesn’t believe in God, he doesn’t know that God doesn’t exist and to admit uncertainty is not a weakness but a willingness to be open to possibilities. A review of my novel described it as “an exploration of the transforming potential of great writing, with Self as modern-day Shaman and spirit guide.” Indeed, I felt an odd urge to make a confession to the literary high priest before me. I’d been carrying a sadness inside me all the way through the publication of The Quiddity of Will Self. I’d done all my publicity in a kind of daze, stuttering through radio interviews, stumbling through readings, flailing through rounds of Literary Death Match. And, I blurted out to him that, not long before Quiddity had been published, my mother had died.

The first short story I ever read by Self was The North London Book of the Dead. It was written back in the late 90s after his own mother had passed away, and now the story resonated with fresh meanings. I worried after I had made my confession that I was going to burst into tears because I was still at that stage in the grieving process when people would come up and ask me how my mum was and when I had to tell them that cancer had defeated her, I’d have to smile really hard and look incredibly cruel, such was the intensity of my inner fight, because there is nothing I hate more than crying in public. Self was sympathetic. I swerved the subject and told him that I was now looking after my father, who had a nervous breakdown when I was three and developed schizophrenia. I think Self realized then that my interest in his fiction went beyond his sesquipedalian prose style – it had appealed because he writes about extraordinary things that were my ordinary.

Madness is a theme he has explored throughout his twenty-year career, from The Quantity Theory of Insanity, right through to Umbrella, where the heroine, Audrey Dearth, is locked away in an asylum, though she is not insane but suffering from the 1920s sleeping sickness encephalitis lethargica. Self captures the daily quiddity of madness, that mixture of the demotic and the mandarin, the way that the mad cope with their condition by an imposed mundanity. My father is obsessed with lists, with routine – supermarket Asda on Tuesdays and Fridays, BBC One’s Songs of Praise on Sundays. A particularly profound point that Self made recently was on the relationship between madness and poverty, which led me to recall how hard it was when father was locked away when I was three and we had to survive on benefits for years. Under our current Conservative government, who are busy slashing welfare and stigmatizing anyone who dare claims it, I wonder how we might have coped.

The lunch ended on a warm note. He noted that I had eaten little and I replied that I’d found his conversation more interesting. He eyed up my yellow soup and half-eaten fries and replied with a dry smile, “Well, looking at your food, it’s not really much of a compliment, is it?”

He was kind and paid for the lunch and told me to keep in touch and I was just relieved that I hadn’t come across as a mad stalker and he seemed to think I was OK. But the trouble with the present is that it is numbing, deceptive and hard to analyze, and when the present became past, became subject to analysis in the following days, I worried that I had been too star struck and dull. So I sent him an email saying, “I’m sorry if I was a boring c**t” to which he replied that if so, “then I was didactic prick,” after which I felt satisfied that we had bonded in some way.

In the wider sense, our narcissistic narratives extend beyond the personal: not only must we be the center of our own narratives, but the narrative of the world (and for some, the universe) must be in sympathy with our story. In The Sense of an Ending, Frank Kermode’s seminal essay – couched in prose like treacle, (but treacle that glimmers with the sugar crystals of genius) – he explores how homo sapiens are addicted to the idea of being born in media res. As the year 1000 approached there was a Millennial Panic and the monasteries made a fortune from the hysterical populace passing over their gems and heirlooms, hoping it might earn them a little more grace and tip the balance in favor of winning a place with a mortgage Up There rather than Down Below. In 2000, the Apocalypse was a 50/50 share between religion and technology. On the one hand, there were the Americans convinced that the Rapture was about to take place – indeed one woman died by jumping from a car sunroof, for she saw what she thought was Jesus by the roadside and twelve figures rising into the sky. (In reality, Jesus was a guy on his way to a toga party and the figures were helium dolls that had escaped from a truck). On the other, everyone was convinced that technology, the exoskeleton holding up the world’s structure, was going to collapse because computers only counted the last two digits of each year and thus 2000 would utterly confound them.

It was to be a sort of Rapture for Microsoft, and so there was something of a collective disappointment when we all woke up and computers hummed along merrily and the ATM machines carried on spitting out money and insurance premiums obeyed their direct debits. Were we disappointed because life carried on its 9-5 grind as usual – or was it also a reflection of a feeling of indifference from Life itself? A hint that life wasn’t much interested in the narratives we impose on it, a clue that when we die it won’t be accompanied by crashing of all computer systems and thunder in the sky and angels in clouds with clipboards and manuscripts of our lives written on them, that at some point in the future when we slip away on a hospital bed or dive under that bus and decorate the tires with our blood, that Life will carry on regardless, the internet intact, the clouds bright with sunshine, the birds whistling on.

That is why we are all in love with the narrative of Global Warming. I’m not disputing that the Earth is warming up, but we did it, we created it, and I believe it is more than a side effect of technology, a reflection of the way our collective unconscious wanted to create a scenario where we created two possible endings – as in a Chose Your Own Adventure Novel – if we keep smearing carbon footprints everywhere, then we go to page 89 (apocalypse) and if we are more loving to the ozone, we get to go to page 90 (life stabilizes). It creates a sense of choice, of control, and at least if the world is going to end, then we made it happen – it wasn’t random or cruel, like the meteorite that struck the Earth millions of years and smote the dinosaurs into fossils.

The last lines on the last page of The Quiddity of Will Self are “I am lost for words.” Like I said at the beginning of this essay, I’m not good at endings. I was disappointed when Umbrella didn’t win the Booker. Perhaps Self’s life will mirror my art – but I do hope we don’t have to wait until 2043 for him to win a prize that he should have been awarded long ago.

Adult patients with encephalitis present with acute onset of fever, headache, confusion, and sometimes seizures. Younger children or infants may present irritability, poor appetite and fever. ^:^,

Look at the most interesting article on our personal internet site

http://livinghealthybulletin.com