“FIFTEEN, SIXTEEN, SEVENTEEN, eighteen…” The numbers are not just in the teens, but tens of thousands. They tick up like seconds. “Do I have 19? Nineteen,” a man with a polished voice says. “Let’s round it up to twenty.” At which point I realize I need to record the proceedings or video them, but capture them in some way, definitely.

A woman whose face is not her face after so much work on it stands along the wall with a man in a sports coat. She raises her hand to buy a Peter Doig, a beautiful one of a burning sky and silhouetted pines, for GBP 550,000, and the way the money and numbers go up, I could be seduced into thinking if I had a spare twenty grand I should buy one of the more modest works for sale here. They seem like a bargain.

And what would you do with a spare $770k or so?

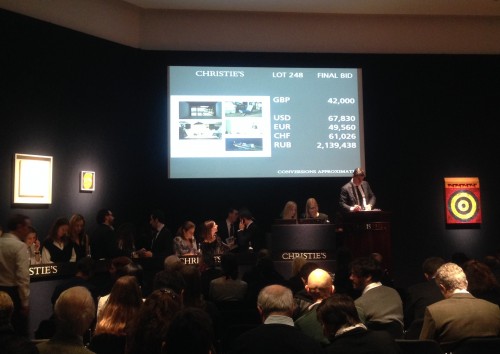

On a large screen at the front prices are listed in various currencies: British pounds and US dollars, euros, Swiss francs and rubles. The auctioneer leans forward conspiratorially on his pulpit. He wears a dark suit, his hair glossed and parted. His accent is impossible to place, maybe German, maybe English, with perhaps a Slavic roll and rumble too as if he comes from some unidentifiable Euro Zone country, maybe one of the tiny ones created from the fall of the Soviet Union, maybe one that doesn’t even exist. He keeps up a steady banter: “Looks like a Richard Serra to me and looking good,” or “Sarah Lucas with a wonderful show at the Whitechapel.”

Throughout, a low thrum of voices and the ringing of cell phones quiver in the air. It’s not impolite to talk or take a call here. You might be speaking to a client to place a bid on her behalf. A few feet away an American man with white hair and casual clothes that do not bespeak obscene wealth says to the person next to him, “I used to have a gallery; now I’m an art advisor.”

This is Christie’s Post-War and Contemporary Art Auction on October 19th in London. The only auctions I’ve been to are in upstate New York where everything from old farm implements to hunting rifles are auctioned off by men with barrel chests and pearl button shirts. Despite the scene at Christie’s today, this isn’t like the sales last month in New York where impossible records were set for works of art. This is a day sale, so comparatively small, and in the low light paintings blaze from the black baize walls. There’s not just the Peter Doig, but Yayoi Kusama (who recently had a retrospective at the Whitney) and Christopher Wool with one now at the Guggenheim, and Sturtevant, famous for her copies of others’ works. The air has the clarified feel of pure oxygen like casinos where it’s pumped in, and like Las Vegas, it’s impossible to tell if it’s night or day outside. The feeling is of high-stakes gambling, as if you might get caught up in the need to win. The scene lures me as I lean against the wall at the back, writing prices in the catalogue, holding iPhone in hand as if I too might be waiting to talk to some client in Hong Kong, or Rio or LA.

When the woman whose face isn’t her face in her leather pants and quilted ski vest (some designer fantasy of ski gear which will never see the side of a ski slope), bids on the Peter Doig, she doesn’t even raise a paddle, just two fingers and those not even high, not above her head, not even to her shoulder. The gesture is perceptible only to the auctioneer and me because I can’t help but stare. Does he know at the outset she’s here to bid for that one painting? As soon as she wins, she leaves with her companion in tow as if all she wanted was this image of pine trees set against a sky alight.

Long boxes line the front and side almost like an elevated orchestra pit with Christie’s name emblazoned in gold on the front. Men and women, specialists they’re called, talk on phones to bidders. The representatives smile and laugh as if sharing a joke with old friends, only I’ve heard rumors, not about this auction but auctions in general, that the specialists aren’t necessarily speaking to anyone but trying to make it look like they’re taking bids. Sometimes one will cup a hand to her mouth when something like price or money is discussed so nobody can read her lips. A woman in red smiles, her head cocked watching the auctioneer intently. Next she’s on the phone leaning forward, absorbed in whatever conversation she’s having. Finally she’s head down, hand to her brow in some sign of woe. Seconds have passed; a whole human drama unfolds. Meanwhile the auctioneer declares a painting is “small but beautiful” talking about a canvas of white latex and nails listed as “Property From An Important Dutch Collector” in the catalogue.

Life’s small dramas in red with Yayoi Kusama

I’m not here for the dizzying array of wealth and art but instead something conceptual, an auction of an auction. It’s the completion of a piece by artist and filmmaker Amie Siegel, being sold here today. Her movie Provenance traces the “trafficking” (her word—I couldn’t have picked one better) in furniture and objects from the Indian city of Chandigarh to the homes of the elite via auction, which in her handling becomes a meditation on price, value and consumption.

The film had its first showing this September as an installation in a New York gallery, Simon Preston on the Lower East Side, and is here at Christie’s a couple weeks later. The timing is compressed. Usually years pass between the show and the auction, and usually it’s a collector who puts a piece up for sale (often when an artist is having a museum retrospective and the work’s value peaks. Witness the sale of the Wool, say.) Instead Siegel put up the film as part of her piece, while the footage of today’s auction becomes the third element in any future exhibitions. The project now includes Proof, a printer’s proof of the auction catalogue, Provenance, and Lot 248, her actual lot number depicting the sale of the film about sales and value…. Provenance the film is now forever tied to the market, both the one depicted in the movie and the one it partakes in, giving it much meta oomph.

Siegel slides from one camera to the next along the wall at Christie’s. She’s plainly dressed, her brown hair pulled back, and she ducks under and around the lenses careful not to get in frame. Later she says, “Auctions have reached a level of caricature these days,” with their stratospheric prices and the press both praising and lamenting (often in the same articles) the heady atmosphere. Contemporary art is the ultimate “luxury good,” as the New Yorker recently put it. Unhinged from any use-value, art is esoteric and incomprehensible to those without the right education. Nothing else establishes one’s place in the elite like dropping untold hundreds of thousands or millions at auction. And, any field that takes that much wealth and something where the value is so enormous and so hard to qualify, is fascinating.

Still, Christie’s was game. It was aware all along of the critique in Siegel’s very sale. “Simultaneously,” she explains, “I was speaking to two of the other big firms (which you can read as including arch-rival Sotheby’s) about working with them, but the head of sales at Christie’s was interested and generous. They know it’s to their benefit to embrace a certain criticality.” Provenance though, the original film shown as art and auctioned as art, is all about furniture.

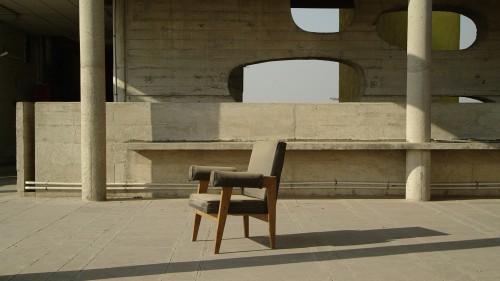

It’s a 40-minute movie about armchairs with no voiceover, no music, just ambient sound, and it’s probably the best movie about chairs you’ll ever see. It starts in rich people’s homes in New York and London, Paris and on the open sea where yacht doors slide open as if triggered by some ghostly presence. In a Paris apartment a barefoot teen runs down stairs past a wooden chair. In a New York loft a baby plays near a table. In the yacht a glass elevator (itself bespeaking the owner’s wealth: the yacht so big it needs an elevator) opens and closes on a floor with one lone chair visible, and then on another floor with two. The gesture is suffused with deadpan humor. For each scene an establishing shot sets the place: a crescent of houses and Portland stone church in Notting Hill, a library in Paris, in New York a doorman polishing the brass outside an expensive address on the Upper East Side, and crashing waves for the Hamptons where the camera pulls back through the dunes to a house slung long and low against the landscape. Throughout, there’s one common element: languid, loving shots of furniture. The camera lingers on chair legs as if they were a woman’s. It’s almost furni-porn, and the furniture is blocky and modern, chairs with arms padded thick enough to be a falconer’s gauntlet.

Amie Siegel, Provenance (still) 2013

HD video, color, sound 40′ 30″. Image courtesy the artist and Simon Preston, New York.

We follow the chairs and the occasional desk or sofa to a scene very much like the one at Christie’s. Here the breathless exchanges I’ve just witnessed are played out again. People stroll around the pieces and sigh and nod at a sale preview. Two men with leather shoes and leather satchels, tweed jackets, sweaters and shaggy hair – all of which adds up to a look I’d call Euro intellectual as if out of a Bolaño novel – circle a set of chairs. Next, a woman in shiny high boots strolls past, arms crossed. Meanwhile in the onscreen auctions, the prices tick stratospherically upward, often as high as the art in London.

From there, chairs are ushered into photography studios and shot against white scrims for auction catalogues. The whole business of creating value is unfolded. Two seats are shown together; a woman directs an assistant to move one a fraction. The shutter clicks, and I marvel at her skill and how she – out of frame except for her voice – knows they will look better moved ever so slightly. We slip back in time again as a furniture restorer rips stuffing from a sofa like gutting a deer. The air fills with clouds of dust and rotting upholstery. Back yet again the scene moves to vast shipping containers across the ocean, and back and back and back to the foothills of the Himalayas. Here, we end up in Chandigarh in India, with monkeys scrambling over the facades of concrete modernist buildings. We’re following the chairs’ path in reverse.

Amie Siegel, Provenance (still) 2013

HD video, color, sound 40′ 30″. Image courtesy the artist and Simon Preston, New York.

In Chandigarh stacks of them, which – if we believe the auction prices in Provenance – are worth millions, stand broken and exposed to the elements. Cameras lead into government offices; bureaucrats talk on phones, and new task chairs and cubicles are still covered in plastic. You can practically smell the formaldehyde. A sole blocky chair holds shaggy folders from which papers spill. A desk bows under the weight of files. A man lies on a building’s roof, shoes off, music playing from his cell phone. Behind him – a wooden cabinet. The film tells an origin story of sorts, but it depends on your knowing who made the furniture and why. Designed by Le Corbusier and his cousin, Pierre Jeanneret, it was made specifically for Chandigarh. In the 1947 partition between Pakistan and India, the Punjab was split, and Lahore, which had been the capital, went to Pakistan. Nehru established Chandigarh as the new capital. A city built from scratch, the metropolis was to be modern, rational, ordered – the opposite of colonial India. And, Corb the architect selected to build it. He wanted a city of peace. In the film a camera pauses on a print of him in a government building. Titled “Le Corbusier, the great architect,” the image is hand-tinted with bold pinks like a Civil War portrait.

Chandigarh is fifty this year, and it was meant to embody the future, what urban planning and good architecture could bring India. Standing watch over it is Corb’s giant Open-Hand statue. Meant as a gesture of peace and possibility in a post-war world, the abstract Hand seems ironic now considering the violence along this part of the border. Just visiting the capital is tricky, requiring multiple identity checks first at the police headquarters then the secretariat. No cameras are allowed into government buildings (to prevent terrorism), making Siegel’s film itself an achievement. Meanwhile guards with machine guns dot the perimeters. One subtext here is the failure of modernism and its idea that architecture and design could improve the world.

Amie Siegel, Provenance (still) 2013

HD video, color, sound 40′ 30″. Image courtesy the artist and Simon Preston, New York.

The notion that a building, an object, a chair, in its very design could cure intractable problems seems quaint today. That tower blocks and high-rise housing projects would forever eradicate poverty? The punch line is they ended up being ghettos. The Bauhaus kitchen created by Benita Koch-Otte used scientific management (like those time-motion studies for production lines) to try to reduce women’s labor and fix sexual inequality. Architecture was going to provide a machine for living as Corb himself said in 1923.

It was “the promise,” which is the name of a show on these issues at the Arnolfini in Bristol next summer. And, it’s strange to think we ever believed this possible. It was a moment—not just one but decades—of optimism. We could design out poverty and ignorance and enslaving women’s work, and Chandigarh was the embodiment of such values. In Corb’s vision people would gather under the Open Hand for free-form debates. For years though, no one, not even local citizens, could visit it. The city was to be the home of a post-colonial world, so the irony of the future is seeing the pieces now flayed, fetishized and turned into nothing but stuff, signifiers of wealth for the very, very rich – in the West.

The film is a study of the power of objects and what happens when they’re stripped of their circumstances and context. Or, so it seems. But the moral equation, Siegel shows, is ambiguous at best. Looking at the desks and shelves Corbusier and Jeanneret designed, now laden with files in some Kafkaesque bureaucracy, it’s clear modernism didn’t make life sleeker or easier or cleaner. The only people who can escape entropy are those who can afford to keep it at bay. Also the idea that after a half century, people should use the same office chair is plainly naïve. This is not to say I think cubicles make offices functional. (There’s a whole other essay in the origins and social meaning of the cubicle).

Years ago I interviewed Rolf Fehlbaum, the master of chairs himself. The head of Vitra, he both manufactures office chairs and puts them in his own museum. In his roundabout and intelligent way he said, “With chairs, particularly office chairs, they have mechanical parts which can constantly be improved, so there is progress. You can still sit in a Thonet chair from 1850 in a restaurant for an hour and be fine, but you wouldn’t want to sit in an office chair from 1900.” Indeed. And, he’s not slowed in making them, nor have other respected office furniture manufacturers like Steelcase or Herman Miller, known like Fehbaum for working with exceptional architects and designers. (Herman Miller, in fact, created the first cubicle.) Fehlbaum went on to talk about how, “when the design movement started, the aim was clear; the task was clear. It was to make an honest contemporary product. Never did these authors think of making an icon. That was never the goal. In its early days, design existed to make an honest contemporary product, but some ended up becoming icons.” Follow the film, and in 40 minutes you can see exactly how that process transpires.

Watching it, I think of the very word “design.” Much like modernism, it’s slipped from being something of use to a status symbol that goes unused. In Provenance no one ever sits in the chairs in the rich people’s homes. The furniture serves as decoration only. Design has gone from something instilled with values (liberal and progressive though they are) to something reduced to value, to a luxury good.

I began writing about design because it was not art. Design is anonymous and humble and accessible, or so it seemed to me when I started nearly twenty years ago. We all had pens and cars and used sip lids, and someone had shaped those things from the small feedback you get when you close a pen to the sound a car door makes when it’s shut. Only over the last decade, that word “design” has slipped free from its moorings and meaning. Design is no longer a verb, “to design,” where I might describe the process of how something is made. Instead it’s an adjective synonymous with style and money. The film shows that process unfolding on a global scale. Chandigarh was designed to embody order and progress. They were inscribed in everything made for the city – even the sewer covers. Its street grid was replicated on them, and one even sold at auction in the film for more than twelve thousand dollars. Now, I mourn the loss of the promise, naïve though it might be. I mean, isn’t the world better when we aspire to improving it? Where we at least try? When solving impossible-seeming problems is written into the very form and function of our products and buildings?

Back in the room at Christie’s with the black felt walls, the auctioneer with his unplaceable accent says, “Thirty-five thousand.” He waits, the pause a punctuation. “Thirty five thousand pounds.” There’s a small inflection, a tiny rise to the word “pounds,” as if an invitation. Each amount gets repeated, and his voice, the pauses and repetitions are irresistible. “Thirty-eight thousand. Thirty-eight thousand pounds, and thirty-nine. Fair warning, 39.”

This is Siegel’s film being auctioned off. The four other editions sold at her gallery this fall. This is the last copy left, and somehow undetectable to the human ear, the price rises from 39 to 42. I’m not sure how or when. I don’t even see the hands go up. I’m not sure if one of the phone representatives has nodded at the auctioneer. Or, if someone at the front or side has raised a finger or two. The bidding goes so quickly, it’s impossible to follow, and her piece, the film, sells. “Forty-two thousand, now. Forty-two thousand pounds.”

And sold for GBP 42k USD 67k.