“WHO IS ISA GENZKEN?” flashes in a video on MoMA’s website. In it, people outside the museum try to answer the question. “Eye-suh Gen-kin?” one asks the camera. “No, I’m not familiar with that person at all.” A girl in glasses shakes her head and so do two young men. Glasses girl says, “Don’t know that one. Is it a woman or a man?” a guy responds, “I’ve never heard of him” – and registering the reaction on the interviewer’s face quickly adds – “er uh, her.”

The punch line is that she is a she; her name pronounced Ee-suh Gens-kin, and no one’s heard of her. It’s very possible by now that you have. I hope so. I want you to. She’s subject of a major retrospective at MoMA, and I want you to fall in love with her work which is ballsy and out-there and often a tumble of forms, sometimes including trash, building debris and thrift-shop outfits. It can look confusing, or it can look like nothing at all as you take in the course of her career from perfect minimal forms to studies of elements from skyscrapers and buildings as well as monuments (deemed “anti-monumental”) built from foraged stuff.

Her work is hard. It’s not pretty, not even easy to describe or place, and not necessarily easy to “get.” Outside the exhibition stand a riot of mannequins clad in lace and masks. Men don ad-hoc skirts and cowboy hats; a boy wears a mask and feathers and leggings, stockings maybe, made of yellow tubing and a codpiece fashioned from a blindfold that holds more in common with sex toys than kids’ toys. A tower is topped by Philippe Starck’s Ghost chair. There are hula-hoops and scooters. A stuffed monkey hangs on someone’s arm, and a plastic baby goat noses into another mannequin’s legs. Just what is going on here with this small army of Mad Max refugees in a museum? Her Actors, as they’re called, are a stage set, the idea being that we could walk among them as characters ourselves, though this being a museum, being MoMA, we can’t. It’s too tricky to guard the art. Instead, before us the characters run riot almost revealing our hidden secrets and alternate selves as if an X-Ray vision of who we are, the bodies we’d be under our clothes if we’d let out our true nature. And, here among the spray paint and mirrors and construction detritus, there’s something exuberant but also troubling and funny and kind of off too.

Isa Genzken. Schauspieler (Actors) (detail). 2013. Mannequins, clothes, shoes, fabric, and paper, dimensions variable. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Buchholz, Cologne/Berlin. © Isa Genzken. Photo: Jens Ziehe, Berlin.

Genzken is also hard for me, at least where writing is concerned, because there’s an inherent tragedy in her work, and I want to put off discussing it as long as possible – forever if I could, if I thought that the tragedy might be divisible from her output or understanding it. It drives me nuts when women’s biographies are inseparable from what they do – when the tragedy, etc. defines the art or books or whatever else it is we create. In countless reviews and essays recently, words like “lost” or “self-destructive” have been employed, and in almost all this writing – including mine – there is (or will be if you keep reading) reference to her exes. If she were a man, would we identify her through them? I doubt it. I probably wouldn’t even know who they are. This thought troubles me in the exhibition, and now I have you wondering who they are. But so far in her forty-some year career – one that’s spanned several major bodies of work – that question of who is Isa Genzken is always answered in terms of her history and the men in her life. And, that history becomes inescapable once you’re a certain way into the show.

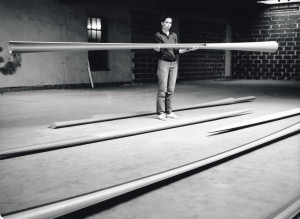

Pass the Actors and you reach a beautifully austere installation of her minimal Ellipsoids and Hyberbolos (her names). Perfectly formed, they touch the ground at one point or two depending on the curve’s arc. These are spare and sparse, and even with these she suffered at the hands of critics who likened the sculptures to knitting needles as if needing to find something literal and feminine in the forms. She responded that the sculptures were arms. She didn’t mean physical ones, not elbows or biceps and wrists, but armaments. Her work is tough and not girly and not about the body or other things with which women artists in the Seventies and Eighties or even the early Nineties were supposed to be concerned.

Also at this point, she forever dispensed with an assistant. To make the Ellipsoids and Hyperbolos she’d worked with a physicist deploying a main-frame computer to get the forms she wanted. As most artists become more successful, they use more and more help in pursuit of their work. Not her. She developed a go-it-alone ethos and decided if she can’t do it herself, she wouldn’t at all. Her fierce independence may well have been achieved at her own peril, but henceforth she worked only with what was available to her.

The artist in her studio, 1982. Image courtesy the artist and Galerie Buchholz, Cologne/Berlin.

Photos of stereo ads hang opposite the sculptures. The one in English describes its Hitachi hi-fi as “the clean and perfect truth.” Other phrases include: “clean and uncomplicated,” “clean and simple,” “perfect” and “near perfect.” This is the early Seventies when minimalism owes itself to the mass-produced serial object, and Genzken is pointing to the hi-fi as the one to top. These “perfect,” “clean” machines are art themselves – or what art should be aiming for, and design, architecture and mass-produced objects become her life’s work, even if it soon hardly resembles classic minimalism.

In the next gallery elegant steel plinths hold concrete blocks that are rubble and architecture as well as a response to minimalism and Berlin’s destruction in the War. Stop, however, in the middle of the room before her resin and steel Window – both the piece’s name and its function. An empty triptych, the Window is as powerful as a medieval altarpiece. It’s transfixing, and it stands under MoMA’s skylight. The windows above mirror the ones she’s made. Look up at the skyscraper towering above, and it’s as if her work was made for this moment of art meeting architecture. This alone is worth MoMA’s (steep) price of admission.

Installation view of the exhibition Isa Genzken: Retrospective. November 23, 2013–March 10, 2014. © 2013 The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photograph: Jonathan Muzikar

Nearby two heads slowly spin, Bonnet I and Bonnet 2. One is called Mann the other Frau, names that mean both man and woman and husband and wife. Formed of rags dripped in epoxy resin, they’re funny, the empty heads. If these two rooms were Genzken’s entire work, here with her paintings of architectural elements reduced to surface and those surface elements emboldened and made 3-dimensional with resin, and these spinning heads, we should celebrate her. In the next gallery, though, trouble, tragedy, brews.

She called much of her work with architecture More Light Research, and this light research becomes literal as she moves from buildings to X-Rays – X-Rays of herself drinking and smoking, and here is the tragedy. Alcoholic and bi-polar, she’s been wracked by plenty of demons, perhaps too whatever scars are endemic in post-war Germany. (One grandparent was a Nazi convicted in the Nuremburg Trials. She met him once, a legacy, I might guess, which is still incalculable). Not long after the X-Rays, her life falls apart. She gets divorced.

She had been married to painter Gerhard Richter, now crowned Germany’s great national treasure and himself the hero-subject of countless career retrospectives at Tate Modern and MoMA and last year for his 80th birthday at Berlin’s Neue Nationalgalerie. (Somehow I don’t recall any mention of Genzken in his show at the Tate). Those spinning empty heads seem like a riff on his abstract paintings and perhaps their marriage. His abstractions are monumental and skilled – and my least favorite works of his. Hers are made by molding soaked (and toxic) rags, and I can’t help but hope one day to see hers hanging before his. She also got him to paint his acclaimed series October 18, 1977 of the Red Army Faction, aka the Baader Meinhoff gang. The title was taken from the date several members were found dead, either from suicide or murder, in their cells. As rumors go she was close to some of them, and according to Judith Thurman in the New Yorker, Genzken might have donated her passport to Andreas Baader.[1] Or not. Regardless, she gave Richter the idea to paint them. The project was to be a collaboration. He’d do the paintings, and she’d build an architectural shrine to contain them, but it never happened, and the couple broke up. Since, he’s been famously reticent about the paintings’ meaning, though you can check them out for yourself on MoMA’s fourth floor. They’re in the museum’s permanent collection and are stunning.

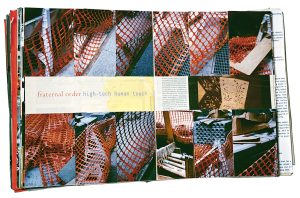

So the heads spin, the bonnets Mann and Frau, empty on their slowly whirring motors, and the marriage breaks down, and she comes to America, to New York. She visits thinking she might move here and stays at the Waldorf Astoria until she’s kicked out, bouncing from hotel to hostel. She is sick, broke and alone. She has no studio, yet she immerses herself in the city and its buildings, taking pictures, collaging the images together in books. Looking at them I get immensely sad because this is what she’s reduced to, photos shot on disposable cameras, and she makes art of what she can, taping together receipts and newspaper headlines and ads into scrapbooks. Called I Love New York, Crazy City, the title alone is ironic and aching, playing off the city’s tourist slogan. What’s amazing, though, is the beauty she finds around her. A couple years later she has a show in Vienna called “Met Life.” The title comes from her looking at the MetLife tower rising above her, yet these two words seem full of hope, of meeting life. Nonetheless looking at the books, I wonder what might have been if she’d had more resources and not been sick and battling herself? In the New York art world she’s dismissed as “crazy” and “difficult,” but she’s still making work about buildings and design, those elements now just slung through collage. There she is layering it all up, taking trash and making something more. She is unstoppable, and for this I love her too.[2]

I Love New York, Crazy City. 1995–96

Paper, gelatin silver and chromogenic color prints, and tape, in three books, each 15 3/8 x 12 5/8 x 2 3/4″ (39 x 32 x 7 cm). Collection the artist

A few years later she’s back in New York with Fuck the Bauhaus, a show celebrating (yes, despite the expletive) Manhattan’s architectural follies and public spaces. Stephanie Weber, a friend who worked on MoMA’s retrospective, took me through it and talked about the frivolousness of New York’s buildings like Philip Johnson’s AT&T tower with its giant kitsch lintel. Genzken wanted to put antennae on top, as if connecting it to her early work with radios and stereos. Now I can’t help but imagine Johnson’s building with these comic ears sticking out, and in Fuck the Bauhaus her maquettes similarly reinterpret the city. She sticks oyster shells leftover from a meal she ate on one building; construction netting covers another like a jaunty pillbox hat, while roses adorn the sides. Built from bright red and yellow Perspex, one transparent tower has “Playbill” on its facade reimagining a Broadway theater. Nearby a toy hula dancer sits on the floor at the foot of a plywood plinth. The models capture the city not the city as it is but as it should be. Or, if you look at it through her eyes, perhaps you truly see New York: Celebratory, wild, full of possibility.

Walter Benjamin has a quote about the urban world: “Not to find one’s way in a city … requires ignorance—nothing more. But to lose oneself in a city – as one loses oneself in a forest—that calls for quite a different schooling.” It’s this city of possibility, of transcendence, that Genzken presents – particularly when that city is New York. She even called her scrapbooks, “A guidebook… for people who wanted to experience New York differently: a lot crazier, more multifaceted and beautiful.” Throughout her work is a love of New York and even America, looking at it post 9/11 and the War On Terror.

Her American Room is named for the space in her London gallery, Hauser & Wirth, where the work was first shown in 2003. A former bank near Piccadilly, the gallery includes a vault called originally the American Room, and here she plays with elements of money, power and imperialism. There are plastic eagles, pine needles and snow globes, a Buddha slashed with red, all ending at a desk on which sits sleek task lighting, an oversized plastic wine glass and in the middle Disney’s Scrooge McDuck, clutching dollar bills. The installation is funny, disarming and weird. It rides a line of kitsch that can seem a bit too familiar, a bit too close to home. There’s something recognizable in it, reflecting back to us what we don’t necessarily want to be reminded of like a relative at Christmas in a garish holiday sweater.

In MoMA’s lobby roller bags adorned with owls, pussycats and puppy dogs stand at a halt, abandoned. NASA astronauts float overhead. It’s part of her installation Oil from the Venice Biennale a few years ago and is a comment on terrorism and travel and the war over oil, but there’s a greater, stranger truth here if you stick with it, if you let the work hit you in that place where it might make you uncomfortable seeing images of fluffy kittens taped to a suitcase.

The show ends with a celebratory proposal for Ground Zero, only her maquette includes nothing an architect would recognize. There are Christmas lights, a plastic skull, an overturned shopping cart and shot glasses. Listing them makes them all too obvious. Her plan includes a 24-hour disco called Disco Soon for the Soon NY club flier she attaches to the building, and Genzken knows the power of dance as a social cure-all. Her Ground Zero memorial towers movingly echo the originals as film negatives trail down the side and two red tubes stick out from the top. The hospital is tied with bows and crowned by a vase of flowers. There’s something essentially surreal in her vision if you take the word “surreal” literally, that is to say, over the real, over the top, even something hyper-literal. How perfect is it to have a hospital topped by flowers? It’s at least as good as Philip Johnson’s lintel gesture, the lintel being a sign linked to the earliest American architecture, a gesture that by the time he got to it had become a kitsch signifier. Her literalness points to a greater truth. Cloaked in silver fabric, her model looks something like a modern glass building, like it might possibly serve the function for which she’s designed it, but tied with a bow and topped with a vase? Shouldn’t all hospitals be?

Isa Genzken. Hospital (Ground Zero), 2008. Each: 122 ¹³/¹⁶ × 24 ¹³/¹⁶ × 29 ¹⁵/¹⁶” (312 × 63 × 76 cm). Collection Charles Asprey Courtesy the artist and Galerie Buchholz, Cologne/Berlin © Isa Genzken

Near the end of the show a guard started talking to Stephanie. The exchange made me nervous. It wasn’t that he was breaking the museum equivalent of the 4th wall, some abstract rule about guards being seen and not heard, not unless you get too close to the art. It was something in the jangly, disconnected quality of his words. He had shorn hair and sunken eyes, and his museum jacket swam around his shoulders. I edged away smiling to keep him at bay as he talked of art school and art now, and his own art and art about money and never making money and driving a cab. He said something about how the only one poorer than an artist was the poet but that art was about money now. I tried to focus on the piece in front of me: sneakers sliced in half and sunflowers seeds, red and silver paint on Buddha, a Barbie and blood. It was a diorama of war, the sculpture itself odd and off, constructed of these repurposed everyday elements. The guard circled around repeating his words and talked to Stephanie about loving the installation Oil. “She’s great. It’s all there,” he said. “Everything, animals, people, technology, the sky, the universe, the carnivalesque.”[3] I turned around and realized it was all here, all in this room with the guard I’d dismissed in his ill-fitting MoMA blazer, the plastic cord trailing his earpiece like a Secret Service agent. He totally got it; he was it. Here in this room with this accumulation of stuff none of which made sense singly, I realized my mistake and wished I’d listened to him the whole time.

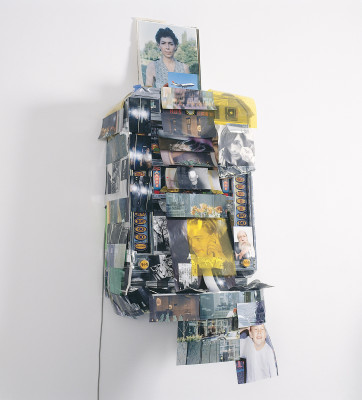

In the show there’s one self-portrait of Genzken, called Spielautomat. The piece literally means “slot machine,” and it’s constructed from one. She made it for a German show on travel (slots like this are popular at German beach resorts). Cobbled together with pictures of her friends and influences, it includes Leo di Caprio and artist Lawrence Weiner. Kai Althoff puts on eyeliner; her pictures of cities are taped on too, and she’s on top in a portrait by close friend, German photographer Wolfgang Tillmans and just below her a jet plane. The piece looks like a gilded icon from a church with the layered effect from the photos and the machine’s yellow plastic and the yellow plastic gels she puts over some of the images. It’s triumphant, and the very nature of the slot machine sums her up: luck, chance, a bit of a gamble and hope. She puts together here all her friends and inspirations as if they build her up, but the thing I want to remember – that I want you to remember – is how she towers above triumphant.

Isa Genzken. Spielautomat (Slot Machine), 1999-2000. Slot machine, paper, chromogenic color prints, and tape. 63 x 25 9/16 x 19 11/16″ (160 x 65 x 50 cm). Private Collection, Berlin. Courtesy Galerie Buchholz, Cologne/Berlin. © Isa Genzken

[1] I know I’d mentioned exes, plural, and the other is noted art historian and critic Benjamin Buchloh. An early champion of her work, he went to school with Andreas Baader and perhaps introduced them. He has also written of the “psychosis” manifest in her later work, a wording that strikes me as unfortunate, though he’s expressing it about the state of consumer culture with which he perceives her engaging and perhaps criticizing. He is also the critic most aligned with Richter.

[2] The retrospective’s hanging underlines her biography and its tragedy by putting the X-Rays here in the same room as the work from her New York trip. Together they point to her disintegration, but the X-Rays were done at the same time as much of her work on architecture, the More Light Research series of paintings. Meanwhile the Bonnets were done at the time of her divorce in 1994, but hung with the MLR paintings, they point to her connection with Richter, a master painter.

[3] Here, I am indebted to both Stephanie Weber and Colleen Asper for their recollections of the conversation, which initially made me too uncomfortable to take in.