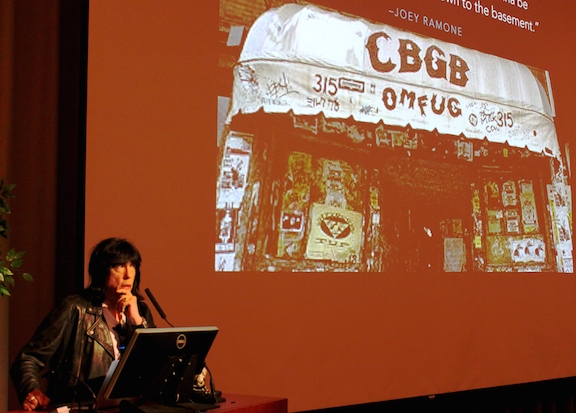

I FIRST WENT to CBGB’s in the summer of 1978, an MC5 album which I’d overpaid for at Bleecker Bob’s tucked under my arm. Chris Frantz, who played drums with the Talking Heads, eyeballed the record jacket and struck up a conversation. Joey Ramone lurked nearby. A band called The Erasers blew piercing shrills through silver whistles and flung nervous riffs from the top of the stage. Marc Bell, who had just left Richard Hell’s band to reinvent himself as Marky Ramone, sprawled on the floor inside the club’s wooden phone booth. A humid discharge oozed from the Bowery. Everything smelled like urine and stale beer.

“CBGB’s was a dump. No doors on the toilets, and the dog that lived there shit all over the place,” recalls Marky on a spring night a lifetime away from the city that no longer exists. “The only good thing about CB’s was the sound system. It was excellent and that’s why a lot of bands wanted to play there. You could sit and watch all these groups that were eventually changing music, like Blondie. It was our home. But I always made sure I knew where the exit was.”

Marky is in Saratoga Springs, a city in upstate New York historically known for healing waters, Victorian architecture, and summer horseracing. A handful of energy bars and two large bottles of sparkling water sit atop the speaker’s podium at Skidmore College where the drummer is preparing to speak to a few hundred college students and aging punk rockers about his life as a Ramone. The student who introduces him tells the audience that the focus of her senior thesis is punk rock.

“It’s a whole new generation out there,” Marky remembers, during a private interview in advance of his appearance, a flop of too-dark hair that contradicting his 57 years on earth. “When we retired in ’96, they weren’t old enough to come to the shows; now at least they get see one Ramone.”

I am 17 years old. It’s Saturday night and the only sign of life in the sleepy East River Queens neighborhood is a restless flicker across living room windows fronting rows of identical brick two-family homes. Weary men in sleeveless undershirts watch Fantasy Island and The Love Boat. The city is broke, trash piled in the streets, some whack job shooting people in their cars because his neighbor’s dog told him to do so.

“New York in the 1970s: there were homeless people all over the streets and garbage strikes,” Marky says. “I lived in a cold-water flat. No hot water. And the tub was in the kitchen. The only thing you could get was cigarettes and beer. That’s how we lived in New York City – Avenue A and 9th Street – and at the time it wasn’t gentrified. It was pretty rough.”

The music, which had delivered salvation, or at least escape to our friends’ older brothers, was dying. The Who ran out of ideas. The Rolling Stones were underwritten by a company that sold men’s cologne. And Lou Reed was making records Lester Bangs likened to taking too many Quaaludes and ending up in bed with a human turnip.

“Disco and stadium rock. Frampton Comes Alive. Ten-minute guitar solos, self-indulgence, and who could play the fastest triplets,” Marky bristles. “After awhile (punk) was a reaction to all that.” He was born and raised in Brooklyn – a hyper kid growing up in the early 1960s who unintentionally got high on model airplane glue and got smacked around by the school dean. The first time he saw Ringo he was inspired and got a job delivering prescription drugs to old people on his bicycle so he could earn enough money to buy a drum kit. “The Beatles were a big influence on me. I saw Ringo on TV and that’s what I wanted to do. I basically copied Ringo, and (later) watched Tommy Ramone, and integrated the two. That’s what you get with me playing the drums the way that I play,” he shrugs. “I’m not Neil Peart.”

By the time he had reached his early twenties, he’d relocated to lower Manhattan, flunked an audition with the New York Dolls, hung out at Max’s Kansas City and released a pair of albums with his high school metal buddies, Dust, before securing a drumming gig with cross-dressing glam-turned-punk pioneer Wayne County.

“I don’t care what anyone’s sexual preferences are but the problem in the mid-70s was there really wasn’t a place for Wayne/Jayne County to play. It was too over the top. A lot of the clubs in that era were owned by the mob and they didn’t want a transvestite to play.” The culture clash came to a head one night in New Jersey. “They stopped the show after five songs, beat up the tour manager, and threw our equipment out of the club. We had to get the hell out of there and back to New York. The only places we could play were CBGB’s and Max’s Kansas City.”

He backed Richard Hell on the Voidoids’ “Blank Generation” and headed to Europe for a four-week tour supporting The Clash. “It was definitely an experience. The thing about England was if they like you, they spat on you. Their definition is called ‘gobbing,’ but it’s really called ‘spitting’ in my book. If somebody spit at me in Brooklyn, it would become a confrontation.”

Patti Smith provided the first sign that salvation was possible, launching a volley of words to the accompaniment of a solemn piano: Jesus died for somebody’s sins, but not mine. Bold, defiant, a sea of possibilities there for the seizing. It blew open doors through which a wave of others poured through: Television and Johnny Thunders, Richard Hell and Talking Heads, the Sex Pistols, the Clash, Blondie and the Ramones. Hey. Ho. Let’s Go. Something was happening downtown.

“I’m in CBGB’s, at the bar, and Dee Dee goes, ‘Marky, you wanna join the Ramones?’ We were like four people that just landed from Mars. We didn’t talk about the weather. We didn’t talk about other things (on stage) like other bands do because they want to rest for that half-minute. We just played down-stroke eighth-notes to cover the holes, and then went into each song in rapid-fire succession.”

Later, standing at the podium, Marky tells the college crowd that he still tours the world playing Ramones covers with his group Blitzkrieg, and that he’s written a memoir that will be published next year. He tells them that he spins punk records on a satellite radio show twice a week, he’s designed a leather-and-denim inspired clothing line for Tommy Hilfiger, and that he markets his own pasta sauce whose recipe was inspired by his grandfather – a head chef at New York’s Copacabana club in the 1940s and ‘50s.

“We get a call that they wanted us to be in a movie called ‘Rock ‘n’ Roll High School.’ At first they considered Cheap Trick, but the director wanted more of a cartoonish-looking band that looked good as a unit, so they wanted the Ramones. So we fly out to California and it was six weeks of waiting around. You wait around for 12 hours and your scene only takes five or ten minutes. I had one line in the movie: ‘that was a good one, Mr. McGree!’ What do you do for the rest of the eleven hours? A lot of our fans would meet us at the fence, because in Hollywood they have a way of knowing where you’re staying. Kids would throw drugs over the fence because I guess they heard about the band’s reputation. I wasn’t a druggie, but Dee Dee was. They would be throwing pot over the fence and pills and Dee Dee would pocket them and eventually take them. I would go, ‘what are you doing, you don’t know what these things are.’ He’d say, ‘oh, no, don’t worry about it.’ He ended up in the hospital twice to get his stomach pumped and then he would come out proudly wearing his armband.”

During the band’s stay in Hollywood, a new opportunity would come literally knocking at the door.

“Here we are making a movie and I get a knock at my door. It’s Phil Spector. He wanted to produce The Ramones. I liked him; Dee Dee liked him; Joey and Johnny didn’t like him, but we became good friends. So, here we are in his car, he’s carrying two guns, his bodyguard is carrying two guns…he was an ex-cop, and we would go along the strip in Hollywood – the Troubadour, the Rainbow, the Whisky – just to hang out. The guy’s five-foot-four, and when he walked in to a club everybody just parted, like it was the Red Sea.

“I went to his Christmas parties every year – yes, he was manic, intense, but usually people who are geniuses are like that. I stayed friends with him until the end, until he went away to jail for 17 years. I feel there wasn’t enough evidence. O.J. got off, so did Robert Blake – from Baretta – and a lot of people out in L.A. were losing faith in the justice system. I feel that they used Phil Spector as an example.

The collaboration with Phil Spector resulted in End of The Century, the Ramones’ greatest commercial success, but one that most fans despised.

“It took about six months to make. The Ramones worked very quick; Phil worked very slow. He had Johnny Ramone play the first chord of ‘Rock ‘n’ Roll High School’ about 50 times in the studio, which took hours, because Phil was looking for a certain sustain on that chord, which eventually we got. That’s how Phil worked. John thought he was just busting his balls, which he wasn’t. We were all new to this. Phil never produced a punk band and The Ramones never worked with a producer like Phil Spector.”

The boys from the Bowery in the land of the rising sun.

“We go to Japan and I’m starting to drink a little more. This is 1980. Here I am drinking this warm sake with Dee Dee. It’s about the ninth bottle, but I’m not feeling anything. We started walking around Tokyo, so what do I do because I’m a big sci-fi fan? I went up to all the Japanese people that would walk past me and I’d go to them: ‘Where’s Godzilla? Where’s Rodan? Where’s Ghidorah the three-headed monster?’ That’s how ridiculous this stuff made you act. I knew it was the sake at this point, because I was ready to walk on all fours. The cops came and picked us up because we were a nuisance. I showed them the key to the hotel and they brought us back. They wanted us off the streets. So we got in the elevator and crawled to our rooms. Dee Dee ended up sleeping in the bath tub.”

Marky flashed a wry smile from the podium at the absurdness of it all. It was a brief gesture followed by a somber tone.

“I had to go to a real rehab with army cots. I washed the floor. I had to wash the toilets. You had to go to these meetings three times a day and that’s when I started learning for real, hey, maybe I’ve got a problem.” The court-ordered rehabilitation was a result of his blacking out behind the wheel of his car and getting arrested after smashing through the glass window of a furniture store. Soon afterwards, he was (temporarily) kicked out of the Ramones. “It taught me a lot about myself, and I’m glad I did it because it could have ended up where I could have killed myself.”

When he earned back his seat behind the drum kit, the group had initiated a relationship with Stephen King.

“I got back in the band again after four years of sobriety and they trusted me now not to get fucked up anymore. The first song I recorded was ‘Pet Sematary.’ Stephen King wrote the book. It took Dee Dee 40 minutes to write the song.

“Stephen King is a very intense guy and a great writer. We went to his house in Maine and had dinner in his basement and if you ever saw the TV series ‘Star Trek’ when you see all the crazy sci-fi looking things – that’s what his basement looked like. A very intense looking guy. You could see it in his eyes. You could tell that he read a lot.”

The crowd eats it up, and why not? These are the first-person recollections of a survivor in a post-CBGB world. When we’d had the opportunity to talk privately he seemed as amazed as anyone that in 2014 The Ramones still mattered. With original drummer Tommy retired and Johnny, Joey, and Dee Dee all having passed on, he takes seriously his role as a leather-jacketed scholar, one of few remaining torch-bearers of the blank generation.

“The kids are younger and younger – 16, 17 years old – and I don’t question it, because it could go away,” he says and shrugs his shoulders beneath a black leather jacket that clings to his torso, still. “When you analyze something…leave it alone.”

“The Ramones just seem to go on and on,” I said.

“It doesn’t end,” he replies, an accent born on Flatbush Avenue accompanying him on the eternal ride. “It doesn’t end.”