AS BLASPHEMOUS AS it may seem to A Song of Ice and Fire purists, the scores of TV viewers willing to shun George R.R. Martin’s literature in an attempt to preserve the series’ thrilling twists and unanticipated deaths for their television screens may be justified in preferring to watch Westeros unravel through the lens of screenwriters D.B. Weiss and David Benioff, rather than the pen of Martin.

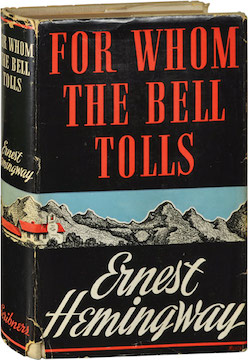

Perhaps no singular scene throughout this past season of Game of Thrones has evinced this fact more than Tyrion’s first appearance in “The Mountain and the Viper” – an expertly crafted work of mise-en-scène that is just part of the reason GOT garnered a high of nineteen Emmy nominations. It’s a brilliant thematic link, almost certainly deliberate, to one of literature’s greatest war novels: Ernest Hemingway’s For Whom the Bell Tolls. Tyrion’s unnerving final encounter with Jamie before his fate was to be decided presented us with a microcosm for Weiss and Benioff’s ability to consolidate Martin’s lengthy prose while simultaneously adding novelty. The incessant debate between book pedants and show fanatics began to dissipate in the dungeons of King’s Landing, as Weiss and Benioff managed to make Martin’s war-torn Westeros eerily similar to that of Hemingway’s war-torn Spain during the late 1930s. It was Hemingway who challenged us to question our detachment to the sanctity of human life, and whether death can ever be associated with plausible justification. Now it’s Weiss and Benioff who are skillfully able to reignite these significant philosophical questions for contemporary society by connecting the author’s 470 pages with a single instance of exceptional writing and filmmaking less than six minutes long.

For Whom the Bell Tolls, published in 1940, follows an American dynamiter named Robert Jordan who, as a member of the International Brigades committed to defeating fascist forces in the Spanish Civil War of 1936, works with a small guerrilla unit in the mountains of Segovia. The premise of the novel as well as the ultimate goal of Jordan is simple: to blow up a bridge in preparation for a Republican offensive. In the days leading up to the attack however, Jordan witnesses ambiguities and hears of Republican-initiated atrocities that cause him to question his justification for fighting and the very political ideologies that guided his arrival.

The ability to link Hemingway’s prose with Tyrion’s monologue stems from the novel’s epigraph from which For Whom the Bell Tolls draws its title. Published in 1624, cleric and poet John Donne wrote a series of “meditations” collectively referred to as Devotions upon Emergent Occasions while recovering from an illness. The seventeenth of these meditations (Meditation XVII) is the most renowned, having much to do with its relation to Hemingway’s novel. In part, it reads:

“No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main. If a clod be washed away by the sea, Europe is the less, as well as if a promontory were, as well as if a manor of thy friend’s or of thine own were: any man’s death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind, and therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.”

In brief, Donne uses land as a metaphor for the indelible collectivity of man, noting that should one piece of a continent be removed, the continent as a whole becomes less than what it was. In turn, Donne argues that the same intertwined fate can be applied to all of mankind. As a species whose origins arise from the same strain, the entirety of humanity suffers upon the perishing of the individual.

As Tyrion anxiously awaits his fate in his damply cramped cell, Jamie’s face appears half illuminated from the shining light from the cellar’s window while the other half remains in darkness, seemingly indicating his current state of moral inaudibility. He struggles with his loyalty to the Iron Throne, which is in direct conflict with the love of his sibling and a desire to save him.

“Trial by combat,” Tyrion says. “Deciding a man’s guilt or innocence in the eyes of the gods by having two other men hack each other to pieces, tells you something about the gods.” Like Robert Jordan, Tyrion questions preconceived notions of what makes up the world around him. Both characters, through their ordeals and tribulations, have come to the understanding that heroism as described in fairy tales does not exist. Just as Hemingway worked to break down the romanticism associated with war, Tyrion similarly points out the paradoxical nature of Westeros’ justice system, and in doing so aligns himself with the cynicism of Hemingway’s prose.

The conversation quickly transitions from apprehension over Tyrion’s potential fate and Oberyn’s abilities as a fighter to one of distractive reminiscence. The seemingly extraneous musings are those that only brothers facing what could potentially be their final moments together have the luxury of sharing during such an ominous time. Tyrion asks Jamie to recall their cousin Orson, dropped on his head as an infant and left simple. They comically recollect Orson’s glossy-eyed fascination with smashing beetles in the garden. But Tyrion’s laughter fades into solemnity as he describes his curiosity with Orson’s morbid hobby and the jubilation that resulted from it. “I may not have been able to speak with Orson, but I observed him, watched him, the way men watch animals to come to a deeper understanding of their behavior,” he says.

“He wasn’t mindless,” he continues. “He had his reasons. I became obsessed with knowing what they were.” Tyrion began to take his meals in the garden, meticulously study Orson, think about his beetle smashing even when it was far away. There had to be a methodical approach to it, in Tyrion’s mind, because even the most moronic men have their reasons for taking life – prejudice, political ideology, paranoia – and one cannot possibly have such detestation for death without justification. Yet no matter how hard he tried, Tyrion remained bewildered by Orson’s addiction.

“I still couldn’t figure out why he was doing it and I had to know because it was horrible that all these beetles should be dying for no reason.”

“Every day around the world men, women and children are murdered by the score. Who gives a dusty fuck about a bunch of beetles?” Jamie replies.

“I know but still, it filled me with dread. Piles and piles and years and years of them. How many countless, living, crawling things? Smashed and dried out and returned to the dirt. In my dreams I found myself standing on a beach made of beetle husks stretching far as the eye can see. I woke up crying, weeping for their shattered little bodies.”

This exchange is the very epicenter of the thematic connection between Weiss and Benioff’s screenwriting, Donne’s prose, and Hemingway’s novel. Jamie, representing the world of Westeros royalty and aristocracy and an upbringing isolated from the kind of adversity associated with that of Tyrion’s – a world in which Tyrion can never inhabit – is oblivious to his affinity for a creature seemingly as insignificant as a beetle. Tyrion’s yearning to understand why heaps of beetles were being smashed without logic or explanation is an attempt to understand the very nature of his own existence. From Jamie’s perspective, which embodies that of the people ready to watch Tyrion die, there are those that deserve our sympathies and those who do not. The incalculable beetle corpses on the other hand, are not worthy of “a dusty fuck.” Yet Tyrion, being seen from the moment he exited his mother’s womb as something lesser, as something inconsequential in the eyes of his family and society, cannot differentiate his plight from that of the beetles.

As Donne’s meditation describes and as Tyrion has come to comprehend, no man or creature of the earth is an island. Orson’s beetles as well as the fascist enemies of Robert Jordan all collectively populate the condition of existence that every organism on this planet is subject to: we’re born, we live, we die. The death of one initiates the diminishment of all. Tyrion is the beetles. The beetles are Tyrion.

His best efforts to stop Orson from his irrational rampage were met only with a swift push aside and the Kung, Kung, Kung of his rock in an unstoppable, rhythmic cadence of death and mindless destruction.

“So, what do you think? Why did he do it? What was it all about?” Tyrion asks Jamie as he somberly looks up at him. A moment of chillingly poignant silence follows as the question lingers in the air in a cold, existentialist mist. The silence preceding Jamie’s “I don’t know” gives Tyrion the best answer this world can offer. There is neither rhyme nor reason behind senseless slaughter. In the same way that the characters of For Whom the Bell Tolls contemplate the similarities between themselves and their enemies, it is a wonder how a sheer matter of evolutionary happenstance – be it region of birth or in the case of Tyrion, a birth defect – can cause such damage.

Rather than a guard outside his cell or a horn blowing from the city’s walls, Weiss and Benioff chose to beckon Tyrion to his fate via the tolling of a bell. It tolled not solely for Tyrion or the beetle accompanying him in the dungeons of King’s Landing. It tolled instead, for every living, breathing creature destroyed by a world that deemed it to be insignificant and regarded its very existence as marginal. It tolled for thee.

Tyrion stumbled to the fighting pit only to witness the same sequence of needless death and futility that bewildered him so much in the garden with Orson, nothing more than a bystander to the smashing of Oberyn’s head as if he were one of his cousin’s insects. A portion of the crowd watched on in jubilation as yet another note was added to the rhythm of the unreasonable cycle of mortality.

Kung, Kung, Kung.

In an episode that features a popular character notorious for displays of sexual deviancy and bravado (that only a member of Dornish royalty could muster) being sent to a brutal and quite literally mind-blowing oblivion, it is a true testament to Weiss and Benioff that the episode’s most haunting scene is a conversation between two brothers in the dark bowels of King’s Landing.

If, as a loyalist to A Song of Ice and Fire, readers still felt the need to admonish the show for its creative license, they were starkly reminded why legions of viewers park in front of their televisions every Sunday at 9 p.m. Game of Thrones is television drama as high art, perched atop an apex of literary adaptations and traditions as towering as the Wall.