1. WHEN I IMAGINED being a mother, I saw myself breastfeeding—slipping open my blouse and sliding my baby’s mouth onto me to nurse, as I’d seen my friends and own mother do. Nice and easy—slip and slide.

Only once, was I able to breastfeed properly. My baby girl was a month old, and I had been pumping exclusively since she had difficulty latching. I put on my hands-free bra, attached the flanges with bottles at the tip and turned on the motor to start pumping. As the baby woke, I drizzled breast milk on her lips so she could get a little bit of energy. Once my milk started flowing out (known ironically as the “let-down”), the baby was handed to me as I disentangled myself from the pumping machine tubes. I slipped on a nipple shield (an artificial nipple worn over the mother’s nipple during a feeding) making my wide, short nipples longer and pointer, then gently put her mouth on my breast. This level of near-impossible orchestration was required to get the timing perfect: she had to be hungry for milk, while having enough energy to nurse, while my own milk was flowing.

2. That was midnight, on my very first Mother’s Day. It was a grotesque almost cyborg-like scene of something I imagined, even witnessed, as effortless. My struggle with breastfeeding became another chapter in the life-long battle with my body: My own expectations, life’s disappointments and my ongoing journey to come to terms with my body.

3. A better mother would have nursed you for at least a year. A better mother would have had smaller nipples. A better mother would have an easier or shorter labor. A better mother would have cut her losses and had a C-section early. A better mother would have chosen a home birth with a midwife instead of a hospital delivery. A better mother would not be absolutely terrified of home birth, even with a midwife. A better mother would not have been terrified of childbirth.

4. During my life, I hated so many other parts of my body—my stomach, my thighs, my ass, that my breasts were the one part I felt confident about. They were bouncy, perky and full. Even as a teenager, I knew they would have a grander purpose—to one day feed my child—and at the time, they sometimes garnered more attention than I would have liked.

When I was pregnant, my breasts grew within the first few weeks from a 36C to a 38DD. They signaled a growing, life-sustaining body. They signaled milk, love, functioning femaleness, that I was, in fact, a mammal doing the most natural thing I could do.

5. I love science. I don’t always understand it, but I love the idea of science. Or, rather, I love the idea of truth. I believe scientists and I believe doctors – most of the time. When I first read eminent-physicist-turned-peerless-eco-feminist Vandana Shiva—who wrote about devastation of land, communities, and bodies in post-Green Revolution India—at an impressionable age, I saw that politics and patriarchy played a role, even in science. Reading Shiva, alongside bell hooks, Edward Said, Catherine McKinnon, and Stuart Hall, threw my intellectually obedient brain into a tailspin. Shiva attacked the very core of science’s professed objectivity as “patriarchy’s project”:

Modern science is projected as a universal, value-free system of knowledge, which has displaced all other belief and knowledge systems by its universality and value neutrality, and by the logic of its method to arrive at objective claims about nature. Yet the dominant stream of modern science, the reductionist or mechanical paradigm… is a specific project of western man, which came into being during the fifteenth and seventeenth centuries as the much-acclaimed Scientific Revolution. [1]

I have since tempered my love for science with an appreciation for subjectivity, relativism and reading between the lines. Then, at 35, I was pregnant. That further shifted my understanding of science, and my relationship to doctors. This understanding continues to shift.

6. While I love science, my first love is literature.

Toni Morrison and Emma Donoghue have written about mother’s milk as the nourishment of life. Mostly, though, I’m haunted by the ending of John Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath, when Rose, after giving birth to a stillborn, breastfeeds a starving man she’s just met:

Rose of Sharon loosened one side of the blanket and bared her breast. “You got to,” she said. She squirmed closer and pulled his head close. “There!” she said. “There.” Her hand moved behind his head and supported it. Her fingers moved gently in his hair. She looked up and across the barn, and her lips came together and smiled mysteriously.[2]

At the time it was written, the last scene was controversial, and John Ford’s movie version did not contain the scene. It remains controversial today, partly because seeing a mother breastfeed her child outside of the privacy of her home is discomforting, and uneven more so seeing a woman as a lactating being.

I certainly did not “smile mysteriously” when I pumped. While my daughter was a newborn, I wrestled with this image of myself, as a lactating being, detached from the baby. I felt not like a mother, or as a martyred Rose of Sharon, or even a wet-nurse, but like a dairy cow.

7. When I was pregnant, I did the required reading by La Leche League, who first published in 1958, The Womanly Art of Breastfeeding. I knew where their meetings were. Even before I was pregnant, I scorned mothers who fed their kids formula. I knew how horrible multinational formula-making corporations like Nestlé were. While I was pregnant, I got two breast-feeding pillows, fenugreek tea, organic nipple cream, shirts, bras and nighties that would allow for easy nursing. Everything breastfeeding promised (especially in William and Martha Sears’ The Baby Book)—higher IQs of baby, fewer food allergies, greater bonding, faster weight loss for mother, better immune system for baby—I supported. A friend of mine started formula feeding after a few days and said she did not have the money for a good breast pump. That friend, I scorned.

What an arrogant, know-it-all mother-to-be I was. Perhaps it’s the curse of motherhood—things you scorn others for will be directed upon yourself.

8. The medical establishment loves breastfeeding. The radical eco-feminists love breastfeeding. I knew everything about breastfeeding—my mom breastfed all three of us. I was eleven when my brother was born and remember seeing my mother’s large purple-brown nipple going into his mouth. I never thought it was unnatural. It never occurred to me that it might be political or even a choice. I don’t remember my mother breastfeeding in public, but maybe she breastfed in the car before we went places. Was my mother a lactivist? Was she practicing attachment parenting? I think she was just parenting—with a combination of inherited Indian wisdom, a dose of Western medicine and some good instincts.

There was no question that I would breastfeed. I actually looked forward to it.

9. Breastfeeding Myths:

Myth # 1. Breastfeeding is cheap. But I couldn’t nurse, so it was very expensive. I paid for three lactation consultants. I bought a high-quality breast pump. I also rented a hospital grade one for four months. I bought a few sets of larger flanges. I then bought a few sets of angled flanges. I had two hands-free bras, six sets of tubes, 25 storage containers, ice-cube trays, five sets of connectors, a car adapter, a battery pack, coolers…. I bought every tea and herb and book I could find to increase my milk supply. I easily spent thousands of dollars to pump breast milk. If I had only formula fed, even with organic formula and the best BPA-free bottles, I would be spending $200/month. With pumping, I easily spent four times that. Also, when one says breast milk is “free,” what assumptions are at play regarding a woman’s economic value? In my case, after my two-month maternity leave, I was supporting a family of four while my husband was going back to school, so being at home was not an option. And the more pressure I felt as the breadwinner, the less milk I was able to produce.

Myth #2 Breastfeeding leads to better bonding with the child. Since I worked full-time teaching and pumped at my office, I missed my daughter for most of the day. And when I was home, I pumped as well. I also spent hours sterilizing pump parts, storing and labeling breast milk, and organizing the fridge and freezer with milk in various stages of freezing and defrosting. I put pumping ahead of sleeping, playing with her, holding her, taking a shower. The pumping was emotionally draining, as was the sense of failure. When I had my couple of hours with her, I was tired and depleted.

Myth #3 Breastfeeding delays menstruation. I was pumping around the clock and for the two months of maternity leave, and my daughter almost exclusively drank breast milk, still eight weeks after my delivery, I bled. I panicked and paged my doctor. She said, “Oh, it sounds like you’re getting your period.” “But I’m breastfeeding. I mean, I’m pumping eight times a day, and that’s all she’s drinking.” Nope, pumping wasn’t hormonally sufficient for me, and it did not stimulate enough prolactin to delay my period. It just isn’t fair to be pumping, feeling postpartum, getting your period and having cramps.

Myth #4 Breastfeeding leads to mother’s weight loss. Without the baby’s stimulation, it’s impossible to produce as much milk from the pump. I had more cravings when I was pumping than I ever had when I was pregnant. I started plotting to buy Hershey bars on my way home, knowing which subway stations exits had candy stores near them. So the weight was stubborn despite breastfeeding.

Myth #5 Breastfeeding feels good. Perhaps it does. Pumping does not physically feel good. It hurts. And, emotionally, the “let-down” of the milk, became an actual “let down” for me, as pumper.

10. A better mother would not have craved so much milk chocolate when she pumped, gaining back the ten pounds she lost during labor, which was you and the placenta. A better mother would have eaten the placenta. A better mother would have harvested your cord blood. A better mother would not think that eating the placenta was gross and the cord-blood-harvesting was a baby-industrial-complex scam. A better mother would not be so cynical about the baby-industrial-complex. A better mother would not be so cynical about the eco-attachment-parenting-cartel. A better mother would not think about cartels and complexes when thinking about babies.

11. For magical thinking at its finest, please see the birth plan that I presented to my obstetrician:

1. I would like to labor for as long as I can with the use of warm compresses, showers and the Jacuzzi. I would like to avoid Pitocin.

2. I would like to minimize tearing and the chance for an episiotomy. I would like to push slowly, to allow my body to stretch naturally as much as possible.

3. Throughout the process, I would like to have communication about the health of the baby and my own comfort, with consideration of my specific concerns about postpartum recovery and pain, so I can make informed medical decisions.

And after the birth of the baby, I would like to

1. Have skin-to-skin contact as soon as possible

2. Have my husband accompany the baby to the nursery for the first bath

3. Begin “rooming” in and breastfeeding as soon as possible, and possibly see a lactation consultant

4. Not have a bottle or pacifier given to the baby.

That was pure fantasy.

Having been influenced by Vandana Shiva, I had my own suspicions about the labor-&-delivery-industrial-complex, making the costs of even a vaginal delivery, astronomically high with unnecessary tests and interventions. I was wary of the prevalence of C-sections. I was told: Don’t have a C-section. Well, I wouldn’t! I switched doctors during my third trimester to deliver my baby at Vassar Brothers Hospital in Poughkeepsie, rather than St. Luke’s Roosevelt in New York City so that I could have my own labor room and nurses who had no more than four laboring women on a given night and a lower-rate of C-sections.

I was in inactive labor for 72 hours (slow leak in amniotic fluid, lower back pain) at home, and active labor in the hospital for 54 hours. Originally, I wanted to labor in a tub, and the hospital had one. But given that I had an amniotic leak, the risk of infection was too high. Pitocin would aggressively induce labor, but I didn’t want it. Instead, I had a Cervidal placed high near the cervix, to “relax and soften” it for uterine contractions. (Anything but relaxing, Cervidal felt like a plastic price tag on a shirt inside me.) After twelve hours with little momentum and dilation, I gave into the dreaded Pitocin. Months of practicing hypno-breathing exercises were no match for the induction medicine, which overrides the natural pauses in labor. The baby’s heart rate kept dropping (one of the drug’s common side effects), but in case I needed emergency anesthesia I wasn’t allowed to eat, which would have helped my energy levels. Without any food, I had no strength to ride through the contractions, and the baby’s heart rate continued to drop.

Cervidal it looks so innocuous here as the hand model holds it in the image here from the cervidal.com website.

Eventually I had an epidural and slept for a few hours,. Then: three hours of pushing and screaming, as the drugs either wore off or didn’t quite hit the right spot. The baby’s heart rate kept dropping, and her head (or my vaginal opening) was at the wrong angle. My doctor said, “Think about a diagonal line” as I pushed. A diagonal?

The pushing was not enough, as I couldn’t quite sort out what the diagonal piece meant. So I needed an episiotomy—a surgical cut in the perineum to enlarge the vaginal opening (second on my birth plan’s list of procedures to avoid). While I was being stitched for thirty minutes, I held my baby for the first time.

12. My obstetrician kept checking in with me, asking if I wanted a C-section. She was reassuring and told me not to feel shame about it. I didn’t want one. I wanted this victory: from my vagina could emerge a baby. I could be a “normal” woman.

My mother had short vaginal deliveries. My husband’s ex had three C-sections, and I heard on more than one occasion, “She can’t really handle pain.” My stepdaughter was terrified that I was having a “natural” childbirth as she had only heard about the pain of labor. Did I fear that judgment from my husband? Did I want to appear fearless to my stepdaughter? Did I want to be like my own mother, and millions of mothers throughout the course of history? The irony, or one irony, is that the labor was not “natural” at all. And, my doctor kept asking gently if I wanted a C-section.

14. A better mother would have made breastfeeding work if she wanted it badly enough. A better mother would have not thought that she may as well go to the movies and the Manu Chao concert if there were some bottles of pumped milk in the fridge for you. A better mother would never have thought that the only upside to not nursing is having mobility for hours at a time. A better mother would never crave mobility. A better mother would get everything from you. A better mother would see you, the daughter she dreamed of, as enough.

15. I had no idea what toll the actual labor was going to take on my body. After eighteen hours of constant IV fluids, I had such bad edema, my legs looked like sausages. In the hospital, I had to use a wheeled baby basinet as a walker. I couldn’t bend to change a diaper or pick up my baby. I could only hold her if someone passed her to me, while I sat. I was not the mother I wished to be. I was not my mother. Was I a mother?

This fluid that was all over my body was also in my breasts. I nursed and screamed in pain. But, I did nurse stubbornly through the pain every few hours. She wouldn’t latch properly, wasn’t drinking much milk, so she developed jaundice. The first night we brought her home, a Friday, she didn’t have a wet diaper. (Wet diapers being the indicator of a newborn’s health). That night at home, she became listless and could barely open her eyes. She was drowsy on and off for the next day, and we rushed the baby to a pediatrician’s home on a Saturday evening. There, my daughter had her first bit of formula, and I started pumping. That night, when she finally peed in my lap, I’d never felt more relief in my life. Yet, I still feel guilty.

16. A better mother would not have allowed you to go 24 hours without a wet diaper. A better mother would not have started pumping and given up on nursing after a week. A better mother would have kept her milk supply up for longer than five months and seventeen days. A better mother would not round that to six months to her friends who actually are better mothers. A better mother would have made a freezer full of breast milk for you to have for one year. A better mother would not have struggled with pumping. A better mother would not have resented pumping. A better mother would have pumped around the clock. A better mother would not have gone back to work after two months.

17. I tried, but I could not discern the differences between the popular and medical literature about what the specific benefits of breastfeeding were. Every Google search yielded the same phrases I’d nearly memorized from the LaLeche League and the Sears’ book. And while I knew the baby-industrial complex of medical-insurance-hospital-profiteering was often in cahoots with peddling formula, I began to wonder if there were another natural-mothering-industrial-complex, a smaller one, with nicer fonts and design, but also laying out agenda-laden information. My literary studies made me question both sides, both the dominant and the revisionist rhetoric.

My questions mushroomed. Were the benefits from breast milk, from the act of nursing?Or, could they be transmitted through the pump and bottle? How much did class and education play into these outcomes for children? Mothers who could afford to breastfeed could likely afford to live in neighborhoods with nice libraries and schools. Like me, these mothers had stacks of pregnancy books and a library for their baby already started, in utero. If pumping leads to less physical and emotional bonding, how much is it worth it? Who could I trust?

Science Meets Breastfeeding.

18. While my first love is literature, my passionate affair is with art.

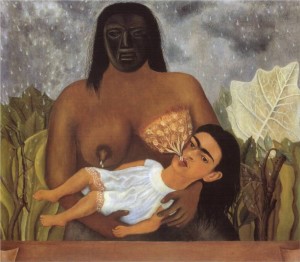

In Frida Kahlo’s painting My Wet Nurse and I, the nursing woman doesn’t smile and wears an Aztec mask. Kahlo depicts herself with an infant body, adult head, and wearing a white, lacy gown, reminiscent of a baptism garment. Milk drips from one of the dark brown nurse’s breasts on Kahlo’s thigh, while botanical patterns are superimposed on the other breast, culminating in a confluence that goes into Kahlo’s mouth. While the images of white leaves, vines, and stems on the right breast suggest fertility and nurturing, the baby and nurse don’t make eye contact. Milk is abundant, flowing from both breasts, affection absent. According to biographer Hayden Herrara, Kahlo’s mother, Matilde, became ill shortly after her birth, and Kahlo was suckled by an Indian wet-nurse, who was employed for a short time until it was rumored that she was fired for drinking.

Frida Kahlo, My Nurse and I, 1937 – about which she said: “I am in my nurse’s arms, with the face of a grownup woman and the body of a little girl, while milk falls from her nipples as if from the heavens.”

Kahlo had no pictures of her nurse, and no memory of her face, so she used a mask, which also represented her interest in Pre-Columbia Mexican identity. A comment on her mestiza heritage and class status, Kahlo has said, “I was fed by a wet-nurse, whose breast were washed immediately before I was suckled”[3] meaning the contents of the nurse’s breast were considered pure enough, but the outer surface of skin had to be cleansed, as if that skin-to-skin contact, another key part of nursing, would make Kahlo dirty.

Since much of Kahlo’s artwork is deeply autobiographical, it is interesting to note that she was never as close to her mother, as she was to her father, who encouraged her to paint. Yet, Kahlo did rush to her mother’s deathbed in 1932, when Matilde died of breast cancer. And in 1937, the year of the painting, Frida had her third miscarriage, confirming that she would never a mother, as she desperately wished.

There are multiple readings of the painting—Kahlo’s isolation as a baby, her difficult attachment with her mother, her own infertility. Yet, one can look deeper at the vegetation. The symmetry of the forms, the delicacy of the vines mirroring the edge of her dress, the leaves composed of drops of milk. While Kahlo was deeply personal in her work, she was also steadfastly Communist and nationalist in her convictions. Having adopted Tehuna dress, she revealed her identification with Mexico’s folkloric traditions and underclass. The Aztec mask, dark skin, and abundant milk could all symbolize the literal fruits of Pre-Columbia Mexico. Beyond her family narrative, perhaps she was revealing that it was Mexico itself, which had nourished her.

19. I searched, but could not find answers specific to mothers who pumped exclusively. Meanwhile, I had real fears. Medically, I worried for her immune system if she didn’t get enough breast milk. And generally, I couldn’t handle the responsibilities of the poor outcomes that supposedly plague non-breastfed babies – low IQ, attention deficit disorder, and picky eating. (I’d already imagined having lively conversations with my daughter, as we ate sushi, injirra and pho). But my deepest fear was emotional, that she wouldn’t be attached to me. When I returned to teaching I found myself busier than I had been in many years. I was plagued with these questions: Did I make bad choices? Should I have had a baby when I was younger with fewer responsibilities? Or older when I was better established with more savings? All this while I fantasized about milk chocolate.

20. In case anyone wondered, reading “AskDr.Sears” site at work, while pumping, didn’t help. Here are some of its recommendations about how to return back to work: Bring your baby to work; Work from Home; Use on-site daycare; Find a nearby daycare providers; Arrange visits from your baby. None of these worked for me, as my commute was about an hour each way; I couldn’t work from home or bring my baby into work; and good-quality childcare was much more affordable where I lived than where I worked. And the kicker was the last one:

Part-Time work: Minimizing the time you spend away from your baby will make breastfeeding easier. Many mothers plan on working only part-time while their children are small – either shorter work days or fewer shifts per week. Others ease back into a full-time schedule slowly as they and their babies are ready.

As the sole provider for a family of four, I realized that I was not the intended reader of this literature, unlike “many mothers.” Remembering Vandana Shiva’s writing about patriarchy and systems of knowledge, I wondered if there was something deeper behind many of the commercially-available books and websites for mothers. For a mother desperate to make sense of her body, her baby’s health and motherhood, I was finding “experts” to be less useful – even frustrating.

21. Anxiety and self-doubt do not lead to bountiful milk supply. Sometimes, when I was at the office, I would look at baby photos. Sometimes, I would Skype with my daughter, as she slept in a rocking swing. Sometimes, I would bring her blanket or onesie with me, so I could smell her. But I was never good at meditation, and my mind would wander.

After she was three months old, her appetite increased, and she needed more milk than I could pump, so I started “supplementing.” To “supplement” means to combine formula with breast milk. To “supplement” was to admit I am not enough.

22. My husband would say things like: “You are breastfeeding. You’re not nursing, but she is having breast milk.” Intellectually, I knew that, but I felt like a failure. I also felt stares from other women, as I bottle fed my own baby with my own milk. I felt judged for being the mother feeding her newborn with a bottle. It was a humbling taste of my own medicine.

23. A better mother would be in the present. A better mother would be in the here and now. A better mother would be so awesome she wouldn’t need to think about being in the present because she just was. A better mother would levitate as the Earth Mother, flowing rivers of milk and wearing tight pre-pregnancy pants. A better mother would not savor that quiet 50-minute bus ride to her office, where she always has work to do, but enjoys looking out the window. A better mother would not figure out how to be in the present only on the bus and unable to be present elsewhere. A better mother would not yearn for more. A better mother would have written in your baby book. A better mother would not be spending time writing this stupid thing and would be writing you a story or reading the Sears book. A better mother wouldn’t need the Sears book because she was so intuitive. A better mother wouldn’t use the word intuitive and would be so consumed by intuition that she wouldn’t even name it as such because she just was and what else could she be?

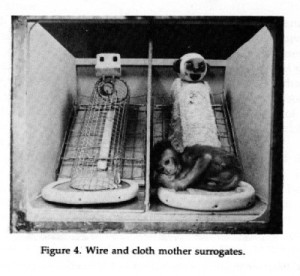

24. In 1960, researcher Harry Harlow[4] was on CBS showing his experiment: a cage; a baby monkey; one “dummy” mother with an ugly wire face and milk and one “dummy” mother made of fluffy terry cloth with no milk. According to the psychologists and pediatricians his contemporaries, the baby should have been strongly attached to the one with milk. Harlow was considered renegade at the time for suggesting that babies crave cuddling, and even need “contact comfort” to survive and thrive. The baby monkey rubbed against the cloth doll, then explored and when he was scared, returned to the cloth mom. When she wasn’t around, the baby monkey was less curious, less likely to explore and take risks.

The key thing to remember is “at the time.” Partially in preparation for suburban bomb shelters, 1960s America boasted new advancements in medicine, plastics and prepared foods – specifically infant formulas. Available for over a century, they were now specifically marketed as better than breast-feeding. (By publishing books, and creating support networks, LaLeche League actively fought against this trend away from breastfeeding that was gaining momentum.) In an era that celebrated the housewife who was often home with the babies the ethos of the time also opposed breastfeeding. People believed holding a crying baby could lead to “spoiled” children who would never become independent. American doctors recommended schedules for feeding and sleeping. “crying-it-out” was a common sleep training strategy. Then there was bottle-feeding with formula. Women would bind their breasts tight after giving birth to stop lactation. (When Betty Draper has her third baby on Mad Men, breastfeeding isn’t even entertained.)

Harlow proved with hundreds of baby monkeys that more than milk a baby needs love. In my earlier images of motherhood, milk and love were one; breastfeeding promoted emotional and nutritional sustenance. As the pumping mother, I felt like Harlow’s wire mother, and I longed to be the terry cloth one.

~

Science provides mystery and awe when one wishes for, or is at least open to, discovery. Science can also be the nexus for confirmation, but I never studied science beyond the most basic college requirements, so even if a scientific study existed that outlined exactly what I ought to have done, chances are I wouldn’t have been able to read it. I was stuck in the genre of commercially-available mass-market medical literature, which meant the science was watered down and likely to fit within an easy ideological perspective.

Instead of breastfeeding for emotional bonding with my baby, I did it for Science. I believed the American Association of Pediatrics who recommends exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months because breast milk is the healthiest thing for a baby. Even though it was expensive, difficult, emotionally and physically painful, I did my best to give as much breast milk to my baby as I could.

My mother, who had no problems with breast-feeding, remarked how miraculous this breast pump, was. For a few months too, I was thrilled to be able to nourish my sweet child. When I was on maternity leave, I would have her sleep on my bare chest, creating skin-to-skin contact, that likely helped keep my milk supply up and made me feel like a mother. When I started working, my attitude changed, drying up my supply slowly. I sought desperately to be a better mother, and that is where the problem lies. I didn’t know how to be one.

The veins of a leaf support its layers and transport water, food and nutrients to the plant. Like the botanical motif on the wetnurse’s breast in Kahlo’s painting. Like the tubes that connect the nipples to the pump. As much as I tried, I couldn’t see the poetry of a woman attaching plastic flanges, connecting tubes, and turning on a breast-pump’s motor. Could the pumping mother be capable, like the Mona Lisa or Rose of Sharon, of smiling “mysteriously?”

I think back to Vandana Shiva and her critique of the algebra of global development, and wondered, does this apply to me, as a young mother? When I read the well-intentioned books by La Leche League, the Sears and dozens of others, I had to question if there was an ideology behind this book and what was that doing to me? Or my baby?

I also think back to The Grapes of Wrath. Rose of Sharon lost everything—her land and livelihood, her husband and her baby. The fiction of the plump California grapes, which called for pickers, drew Rose and the Joads to a desolate and dessicated land. Yet, Rose was not barren. She was lactating and able to nourish. Steinbeck and his editor disagreed about the ending[5]. The editor urged for the man she feeds to be one of the men she knew from the car. The editor wanted the intimacy of the act of breastfeeding to be matched with the intimacy of the relationship between nurse and nursed. Steinbeck insisted his ending stand: the very purpose is that the intimate act becomes hope for something greater than the family unit, perhaps as the man was a stand-in for the American people, desperate at the time for nourishment. Like Kahlo’s nurse, there is milk-making, and there is mothering. Those are two separate acts. Pumping had led me so far from being the mother I desperately longed to be.

At her six-month check-up, my baby finally was well above average in weight and height on all the charts. Taking a long, hard look at her, seeing how strong and energetic she was and how far away we all were from those first few days at the hospital, I decided to stop seeing myself as a milk producer and started to see myself as a mother again. Too many days had passed when I would be at the office all day, and too many evenings when timing would not be on my side, and I’d run home to pump before I could hold her.

At six months, we switched to full formula. The organic kind. But formula, nonetheless.

I’d originally thought of breast milk as a multi-vitamin or wheatgrass—one shot-a-day for the first year. After consulting six pediatricians, I was told to use up all the breast milk I was storing as soon as possible, as it was better for her to have as much breast milk as possible in the first six months than to spread it out over a year. She finished it up by her six-month birthday.

I gave myself my life back and my baby her mother back. I packed up the pump and held her soothingly to my chest.

[1] Vandana Shiva. Staying Alive: Women, Ecology and Survival in IndiaNew Delhi: Kali for Women,1988. p. 15.

[2] Steinback, John. The Grapes of Wrath. New York: Pengiun, 1939. p.455.

[3] Andrea Kettenmann. Frida Kahlo, 1907-1954: Pain and Passion Taschen: Los Angeles, 2003. p. 8

[4] “The Nature of Love” Harry F. Harlow (1958) First published in American Psychologist, 13, 673-685 <http://psychclassics.yorku.ca/Harlow/love.htm>

[5] Patrick J. Keane. “The Senses of an Ending: The Grapes of Wrath, Novel and Film” Numéro Cinq Vol. III, No. 8, August 2012 (link: http://numerocinqmagazine.com/2012/08/27/the-senses-of-an-ending-the-grapes-of-wrath-novel-and-film-patrick-j-keane/)

This broke my heart.

There’s so much pressure on parents- mothers, of course, in particular- to be perfect. But there is no perfect.

My sister has a three-year-old and a six-month-old and she’s breastfed both of them. They are healthy and happy. My mother, however, had two daughters and never even entertained the thought of breastfeeding. We were also healthy and happy.

This “breast is best” bullshit seems to be another way of shaming some women for their “choices”.

So powerful-

Thanks, Marni, for sharing your comments. The pressure on mothers is something else, and in general part of “shaming” women culture!

What a beautiful and beautifully honest essay. And how effectively Swati overcomes the gender barrier as she manages to share a mother’s anxiety over something as fundamental as a desire to properly nurse with an old man

now a well-fulfilled father and grandfather.

Two things stand out for me as I read and re-read the essay. First there’s the anxiety that abounds in a culture where “experts” can so readily broadcast their well researched advice at the risk of turning well intending new parents into neurotics. On the other hand there’s the beautiful anodyne Swati recognizes in John Steinbeck’s powerful metaphor of Rose of Sharon as an archetypal earth mother overcoming social indifference at its harshest. One such image can transcends the research of a thousand well-meaning experts.

So here’s the message I take from this essay. When we want to know what’s best, we’re better off reading novels and poems or heeding the wisdom of everyday folks. Or so I am reminded of as this essay evokes my memories as a newly anxious parent following the birth of my first child, Zoe–wondering how to hold her, how to respond when she cries, how to properly apply a father’s new sensation of selfless love. Turning from the library of experts as her mother and I fumbled with then popular Dr. Spock and the professional advice of others to our good friend Carrah Clayton, by then herself an experienced mother of three flourishing little kids, when we asked her what she thoughts, with a laugh she replied, “She’s your baby; do whatever you want.” Memorable words. In my book of memories she belongs up there with Rose of Sharon.

Hi Paul, I’m touched that you felt the essay crossed the “the gender barrier,” as I played around with the idea of submitting the essay to a mom-oriented site or one for a general audience. Thank you for reading and sharing your comments.

Thank you for writing this…

I couldn’t breastfeed my firstborn for various reasons…stress, pressure, not having enough support, latching issues…it was endless, it seemed. I tried, I pumped and by the end of three months, I threw in the towel.

With my second son, I vowed to try harder and “do a better job”…minus all the stress that surrounded me the last time… Well, I still had latching issues at the hospital…and pressure from the nurses. The night before I was going home, I said to my husband, “Honey, isn’t the most important thing is that the baby drinks the breast milk?” He said, “Yes”. I said,”Well, then does it matter if it comes from my breast or the bottle?”, He said, “No”… and I said, “Then fine, I’m pumping for this baby for as long as I can.” And that was it, I pumped and pumped and got to freeze milk too! I was tired and exhausted as I felt like the breast pump was my child sucking the milk out of me…but hey, the milk is coming out. In the end, I pumped for 6 months and when I decided to stop, I had no regrets. My baby had my milk for 6 whole months! Then he had formula for the next 6…which hubby made every night. I said, “Hey, I made milk for him for 6 months, you can do the same for the next 6”. :)

I found what works for me, not what everyone else says that I should do. I was surprised to find so little material about moms who “exclusively pumped”… my only regret was not having realized this for my first son and done the same for him. Some may say that exclusively pumping takes away from “bonding”… I disagree… I have my entire life to bond with my boys in so many other ways.

Thanks Yvonne, for sharing your thoughts. It sounded like the experience of the first emboldened you to have greater confidence with your second child. And you are so right, so little is written about exclusive pumping, and I couldn’t found lactation consultants who knew much about pumping, outside of nursing. Last year, I wrote this Op-Ed about the battles pumpers face. http://thefeministwire.com/2013/08/op-ed-when-a-mother-chooses-the-pump/ With this piece, I wanted to focus on the toll the experience took. But it sounds like you figured out a great way to exclusively pump, and have enough supply to freeze. But mostly, the success was in your attitude, your ability to make a decision and feel confident about it. And yes, we have lots of time to bond!

What a wonderful piece–I missed it when you first said something about it last week. What an ordeal you went through. I think you might have hit the nail on the head when you wrote “I began to wonder if there were another natural-mothering-industrial-complex, a smaller one, with nicer fonts and design, but also laying out agenda-laden information.” Indeed. The internet age has ushered in unprecedented amounts and angles of maternal judging. I had a much smaller version of this experience, when my son was hospitalized at 10 weeks with gastroenteritis of unknown origin. Long story, but the upshot is that eventually we were told it might be an allergy to…something…so I decided to pump exclusively for 2 months while all of the remnants of soy and dairy made their way out of my body (not a simple thing to eliminate when you’re vegetarian…). And then I was told by a different pediatric gastroenterologist that my son didn’t have any allergies after all and went back to nursing on my normal diet. I still wonder why I pumped during that time and didn’t just use formula from that point on. He would have been fine. At least I was able to donate the ‘contaminated’ breastmilk from that time, so I hope that some child somewhere got the benefit of it. Though, I’m sure that child would’ve been fine on formula too.