This summer Timothy Braun took to the road, traveling the US in search for larger truths, re-enacting (of a sort) Steinbeck’s Travels With Charley. You can read his earlier adventures here and here and here.

Memories and thoughts age, just as people do. But certain thoughts can never age, and certain memories can never fade.

― Haruki Murakami, The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle (1994)

WE WERE SO happy, we were miserable. Me and Dusty, skipping from town to town across the Rocky Mountains, only taking a few moments to speak with people, getting gas, coffee, treats, maybe making a sarcastic joke on Facebook, then disappearing. It’s the way I like it, it’s my style, noncommittal, but it can be exhausting for me, and it is always exhausting for the dog. As we traveled, Dusty sat on a bench I’d built for him out of plywood and old grey carpet and attached to the back seat of the truck. He never lies down and curls up when I drive, he just sits at attention and pants, like a soldier waiting for another exercise. It is like living in a fishbowl for him. We had driven thousands of miles, and I was asking too much of him. He looked out the window, or sometimes at the floor, and waited until we stopped moving so he could nap, or eat ice cream or French fries with strangers. My clothes stank, and his collar smelled. I hadn’t done laundry in weeks, and we were feeling lost even though we had a map.

I have an idea based on nothing that Dusty prefers listening to voices, audio books and podcasts, not my punk rock or sad bastard bands like Sonic Youth on the radio. I played Haruki Murakami’s Wind-Up Bird Chronicles for him, read by a man with a dry, unremarkable voice. We started the book in the desert, at the beginning of our trip, and the dog and I always finish what we start. Murakami is often criticized by the Japanese literary establishment as too Western, too American, too surrealistic, and even melancholic, but that’s why I like him so much. He has reccurring themes of alienation and loneliness, and his characters have a difficult time with what is real and what is fiction, only revealing their true selves when they think no one is looking. Although Murakami is Japanese, I consider him the most American author alive today, and the desert had seemed a good place to start his book, the road a good place to continue it.

As we listened to the girls and lost cats scattered across Murakami’s novel, I drove and daydreamed of my ex-fiancée, her daughter, and the daughter’s father, who all live in Houston. The daughter’s father is an old friend of mine. Just about the time we left Texas, he was getting tired and smelling iron, and his toilet water would turn red as he shit. My relationship with him is so unique that I feel compelled to protect him, or at least worry about him. That, and I love buying the kid toys. Dusty and I took a break at a rest stop in Idaho and left them a message asking if we could visit for the Fourth of July.

“Dusty and I would like to visit…” I said, and got cut off mid-sentence.

At the rest stop, Dusty pooped on gopher holes and I thumbed through the Spider-Man comic books my brother gave me in Seattle. I love my brother; he takes my 13-year-old niece to the Emerald City Comic Book Convention every year, which I think is a great thing to do for a kid. But we’ve grown apart and I already owned the comic books he’d just given me. I don’t read comic books much anymore, and as Dusty pooped and peed I thought about animal villains, focusing my attention on “The Rhino.” Who would come up with such a thing? I sketched ideas for a new monster on a Starbucks napkin, “The Walrus” I called him, a bloodthirsty loner. The Walrus would make for a nifty horror movie; maybe something about lonely animals, a fish out of water story, something with vampires for teenagers. I asked Dusty if this he thought this was a good idea, but he had no response other than the simple wink he gives me when he hears the sound of my voice.

“What am I gonna do with these comic books? I don’t own comic books anymore,” I said. The moments that are just me and the dog are always the most splendid.

There are other moments in life that are perfect. There are 400 flavors of perfect, and the Rocky Mountains were on that scale, inch by inch, moment by moment. The Rockies are cool, but not cold, and not necessarily wonderful, but a collection of colors that inch closer to a hotel painting that no one could ever believe. Boise was also on the perfect scale as well; by far the most bang for our buck the entire trip. We stayed at a bed and breakfast that put us in “Room 2: The Story Suite,” which had a small library including Life of Pi. In Boise we met with an old high school friend I hadn’t seen in forever. Her husband makes music above their garage, and their beautiful daughter, who has a delicate smile, like clarinet keys all in a row, took a liking to Dusty as soon as their eyes met. The girl carried a teddy bear in her backpack, and asked if she could hold Dusty’s leash while we walked before her fencing lesson. We had French fries, ice cream, and piles of hot pizza. At each restaurant and café the girl tied Dusty to the table, then placed her teddy bear in a seat. We walked by the zoo just off Julia Davis drive, where the giraffes dipped their heads over the wall to say hello. Dogs usually bark at giant animals, but Dusty didn’t. Not too far from the zoo was the “Library!” complete with an exclamation point at the end, because a place with that many books should be taken seriously, and they had all the Murakami books and Spider-Man stories the world has every seen. Dusty licked the girl on the cheek, and smiled and winked at me. My dog smiles and winks at me when I talk, but also when he is happy. Perfect moments like these were meant as rewards for Dusty for tolerating the long drives.

Salt Lake City was a drag. Before arriving I’d had the delusion that we would stumble upon a great counterculture in the middle of a land known for Mormonism and boring basketball, but instead I found a town covered in smog with bland Himalayan food and bad traffic. A teenage prostitute — who I’ve since tried to write about a dozen times only to come to the conclusion that she wasn’t really a hooker, but rather a figment of my imagination — highlighted my hotel lobby. The figment and I spoke to each other about Stephen Sondheim lyrics and the price of higher education before she faded away into the ether and smog of Salt Lake. She told me she is re-reading Twilight at home, or so she claimed, because she loves the vampires. She looked like a mannequin in an Old Navy window, with bright colored clothing and plastic skin. I think she was too kind to truly know what she was doing, or, perhaps, she was just playing a long and amazing game with me I didn’t understand. I have no idea why she would tell me she was a prostitute, talking with me, telling me her story for free, all while she could have been making money. The whole town felt like a cardboard cut-out, and she was the mayor. But I’ll give Salt Lake City this: the coffee wasn’t bad. If it weren’t for gas station coffee we’d still be painting mammoth hunts on the side of caves.

The next day we cut across the southern hills of Wyoming and down into Denver, and I was running out of space on my phone to take pictures. I deleted an audio book, Murakami’s Dance, Dance, Dance, and I could I feel my heart murmur again, the pain in my chest, in my arm. Dusty and I got to a hotel, got a pizza, watched the NBS Draft, and crashed hard in the bed. The shifts in altitude must have been affecting me. I woke up to my childhood friend, the editor for Wired Magazine, the one who had suggested I take this trip in the first place, on the CBS Morning News. He was talking about virtual reality — what was real, and what was not, and I couldn’t help but think of the prostitute in Salt Lake City. Later that morning, Dusty and I met yet another old friend at a French café, a man who had been close to me for years, but who had disappeared from the earth for a while, just vanished. When we met, he gave Dusty a pat, ate a croissant, and told me he was now a convicted felon. He was arrested for possession of child pornography, the kind of pornography one only finds in bad places. “It wasn’t my fault,” he told me, but I knew it was. He has lied to me in the past about lesser charges. He asked me not to write about this, and I told him I wouldn’t, but I have to. If I don’t, I’ll break into pieces. I will not name my friend, nor will I describe him. He had been spending time on the “deepweb,” the “darkweb.” I read the media reports: girls ages 8 through 12. He had pictures of these girls, labeled and marked. This was no accident, he couldn’t have just stumbled upon them, as the pictures were found on multiple machines. Later, much later, I’ll contact my buddy from Wired on the pretense of congratulating him on his television, but really to ask about the deepweb, to make certain my information is accurate, and this is what he’ll say: “I don’t have a lot of first-hand experience, but I’m certainly familiar with it. Remember the Silk Road arrest last year? Silk Road was one of the major deepnet, or darknet marketplaces (guns, drugs, kiddie porn, assassinations, everything paid for with bitcoin…). You can access it with a Tor browser, if I remember right.”

I hope that if I ignore a man with child pornography, he’ll evaporate from my memory; that if I write about him, get him off my heart, he’ll go away, but he won’t. Before I took trips with Dusty, I took trips with this man. I’d just learned he might be going to prison, where I fear he will die badly. I don’t want this, I just want him to get help, to have help, and also to never see the girl who walked my dog in Boise, let alone the daughter of my ex-fiancée in Houston. I needed French fries.

Dusty and I explored the rest of Denver, and while we were having those French fries at a café, a drunk and far-gone girl covered in red, green, and blue tattoos walked up to him. She dropped to her knees and licked his face. I laughed and said, “This day is a wash.” I took a picture of her licking my dog, and all Dusty could do was look at me, with an expression in his eyes that said, “Is that it? Is that all there is?”

“For today, maybe,” I told him.

I gave the girl French fries and water and asked her if she knew where she was. She pointed at the park across the street, and crawled away, and then Dusty and I took the rest of the night in Boulder.

Boulder used to be a lovely town, back in the nineties, but all the rich kids have taken over and turned it into a shopping mall. They paved parades and put up a Kid Robot. A cop told me I could not walk Dusty on Pearl Street, emphasizing that this just ain’t the town for us any more, but before we left Pearl Street I bought a kite and chocolates. It didn’t matter that the cop kicked us out anyway. Thurston Moore of Sonic Youth was playing at Naropa University. Dusty and I met him in the parking lot for a brief moment. He was tall and long-legged, and had hands as big as the sky. He waved at Dusty, and Dusty shook his tail.

“You do know you hate his music, right?” I asked the dog as Moore strolled away.

Dusty winked at me.

The next day we crossed into Kansas and I got a truck magnet that reads “My Dog Is Smarter Than Your Honor Student,” because truth is beauty. Dusty sniffed and pooped on flowers and gopher holes again, and at the truck stop I got two coffees as my chest began to hurt. But I like Kansas. The roads are smooth, and well taken care of (that might be the first time the whole trip I noticed how smooth the roads are). And you may not think it, you may not know it, but Kansas is smothered in windmills. Windmills all the way down. We drove through the state on Gay Pride Day, clean through the heart of Topeka, home of the Westborough Baptist church. Kansas there didn’t look like the kind of place where you’d find bigots and fools. It was green with rolling hills and could pass for Scotland in some areas when the clouds are right. No wonder all the cool kids want to play basketball there.

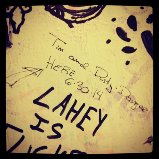

Lawrence was a magical town. They have a clown college. I slammed around the Midwest for most of my twenties; I jokingly say I’ve been thrown out of every bar in Ohio, and out of all the college towns I’ve plundered, Lawrence beats the likes of Bloomington, Indiana and Oxford, Ohio. Dusty and I stayed with a kind couple just north of Lawrence in the country, who made their home from old telephone books and wine bottles. The wife has designed a new way to hitchhike safely and was working with an application company associated with TED in Kansas City. Hitchhiking is faster and more efficient than taking the bus, and for people who live out in the country, there ain’t no bus to begin with. Perhaps Dusty and I will hitchhike our next trip. The sunsets were amazing in Kansas and I can see how people could be tricked into thinking that God made this country for them and only them. Dusty chased chickens, barked at mean eyed cats, and ran through tall wet grass. He smiled and winked at me. That night he put his jaw on my foot and I read to him from the football magazine we’d bought in California. The following day we stayed in a church with the theatre group Rubber Rep in downtown Lawrence, only blocks away from a café smothered in graffiti. I write “Tim and Dusty-Danger Here 6-30-14” with one of my black writing pens. To make room for the picture on my phone I deleted the audio book of Murakami’s 1Q84.

The next day we headed into Missouri, and went to Osage County, our second trip there in two years. That’s where Dusty’s girlfriend — one of his many girlfriends — lives. Katy is a horse, the only large animal besides those giraffes that my dog didn’t bark at. They rubbed noses as they said hello. Outside of seeing Katy, Dusty got to see a murderer’s row of dogs, chickens, friends and ran free, off-leash. We were at the Osage Arts Community, a residency program Dusty and I attended two years ago, a place where I first started writing about Dusty, a still continuing story about how Dusty keeps me grounded during low times. This time we arrived on Mark’s birthday. Mark’s the guy who runs Osage, and we had a small party for him, sat in the river and drank Coke Zero while Dusty splashed and sniffed at turtles, then found a dead armadillo and ate half its rotting shell. It was warm but nice in Osage county, and I wondered if “The Walrus” could survive in a climate like Missouri’s. During the party I text messaged a woman back in Austin that Mark and I both know. She’s an artist, and she and I are both on the board of a theatre company.

“I have something for your son,” I texted.

That night Dusty and I finished The Wind-Up Bird Chronicles, and I deleted it from my phone.

The following day we were supposed to stay at a haunted hotel in Dallas for the Fourth of July, but instead I cancelled and headed to Houston to see my ex-fiancée, her daughter, and her daughter’s father. I wanted to know about this iron smell, and to see the kid. Anyway, if Dusty doesn’t like driving, I can only imagine how he would feel about being stuck in a hotel room with a bunch of ghosts. To get to Texas from Missouri, we had to drive through Oklahoma. Never go to Oklahoma. Not once have I had a good experience in the only state in the union in which not one county voted for President Obama. Every time I go through there, I think they need their own stamp that says “Celebrating 30 years of electricity,” or something to that effect.

Out of our remaining audio books, Dusty and I listened to the Bullseye podcast to make Oklahoma easier, the same podcast about pop culture we’d started listening to in California. We listened to the interview with Judy Greer over and over again, and took it all in. Greer has a kind, yet fun voice, like honey dipped in thought crimes, and for the first time in our trip, all 6,000 miles of it, Dusty actually relaxed on the bench I’d built for him as we drove. Greer reminds me of my ex-fiancée: both are actresses with sharp comic timing, and as she talked about a cartoon she did a voiceover for, I got ideas on what to do with my walrus. Maybe he wasn’t so bloodthirsty, just an animal out of his depth.

Entering Texas, a thunderstorm slammed down upon us. Maybe it was God’s way of punishing me for criticizing Oklahoma. Dusty does not do well during storms, and began to whimper. I turned off the radio so I could listen to him breathe. My chest hurt. A car not more than a mile in front of us slid off the road and burst into flames as it hit a pine tree, and a rescue crew soon rushed in, stopped all traffic in the midst of the flooding and the monsoon, and yet it still felt like we were moving — inch by inch, foot by foot.

Houston has a lack of radio stations, and I don’t know why. You’ll find unworkably horrible music, or Spanish language commentary, but little else. We got to my ex-fiancée’s and had chicken and macaroni and cheese. Her two-year-old daughter played with Dusty, his tail amusing her as it wagged. Dusty is good with young children and appreciated the high-pitched squeals she made when he licked her face. While we ate, I told the daughter about the giraffe and the French fries. I showed her the tattoo I got in L.A., and talked to her about Boise. I gave she and her mom the kite and the chocolates I got on Pearl Street in Boulder. The last time I’d been in Boulder my ex-fianceé had been with me, when she was just my fianceé.

The next day we played on the slabs of rubber ground that shoot water upward at the park near Galveston Bay, a small park that Dusty is not allowed in. The daughter’s father told me, “I’ve got cancer now,” something I’d feared. He has a solid chance of survival, but it made me angry and I didn’t know what to tell him, so we talked about sports and kids toys before I bought us four kinds of ice cream. It’s a shame there is no ice cream parlor called “Four Hundred Flavors of Perfect.” That night Dusty and I sat on the back porch and watched the neighbors firing gunshots into the clouds: Texas on the Fourth of July.

The next day we got home to Austin. It was hot and muggy, and the air sat on us. I did the laundry, paid the bills, and saw Louis, the 13-year-old son of my artist friend. He reads nothing but comic books, owns more comics than anyone I know. “I have something for you from my trip,” I said, “My brother gave it to me.” I gave him the Spider-Man issues. Louis is the same age as my niece, and, like my niece, he seems bored by me. Given the option between a video game about ninjas and a zombies, or talking with me about all the trouble Dusty and I got into, it was clear that I, as usual, took the red ribbon.

“The Austin Comic Book Convention is coming up, if you would like to go.” I said.

“Cool.” He replied noncommitally.

Dusty and I left him to his video games, went home, turned on the TV, and saw that Judy Greer had a new show on FX called “Married.”

A month later I was in New York on business, away without Dusty. I’d hired a member of Bird & Anchors, an all-women’s bluegrass band in Austin, to watch him. In Manhattan I went to 195 Claremont on the Upper West Side, the place where I first met my ex-fiancé, and took a picture of myself standing in front of the door. It was 15 years since I had moved into that building, the first home I ever had in New York City, when I went to Columbia University, and although I left a decade ago I still refer to myself as a New Yorker. The building looked different: the deli directly below my apartment was gone and gutted. Around the corner were new and shiny box-like buildings. New buildings were popping up all across the neighborhood, my alma mater’s neighborhood. So many of the prewar buildings I recalled had been replaced with giant Legos. I took almost no pictures when I lived in this place, the memories of school have almost faded, and when all the buildings have been replaced, I’m sure I won’t remember a thing. I bought a faded blue T-shirt that reads “Columbia University” at the bookstore so I would never forget, then walked down Amsterdam Ave. to Sarabeth’s to have breakfast with my agent. I told her my new idea for a new project. “I call it Walrus Vampire,” I said. “It’s a cartoon about a lonely Walrus exploring the world with his pet, um, octopus, an octopus in a bowl who hates to travel. They do self-reflections along the way. Sort of like Louis C.K.’s show, but a cartoon walrus.”

“Sounds like you could write that,” she said. “But why a vampire?”

“Chicks dig vampires. That, and I won’t exploit the positives of being supernatural; it’s all about negotiating his weaknesses in a world he feels wrong for. The only person he can relate to is his pet, and his pet isn’t even a person.”

“I like it. Get me a treatment. You got actors in mind?”

“Judy Greer.”

“For the walrus?”

“No. I just like her. My dog likes her voice.”

As we talked, and as I ate eggs and drank enough coffee to make my chest hurt, Dusty was having a birthday party back in Austin. He’d just turned nine. His dogsitter had her band come to our condo and serenaded him while guests had hot dogs and blue jell-o shots that looked like water dishes. Dusty had his other girlfriend, an Australian Shepherd named Charlie, over too. A special cake was made out of carrots and peanut butter, shaped like a giant bone. My dog eats better than most humans. Waiting for my JetBlue flight home from Kennedy, I flipped through the pictures of Dusty on my phone. I take so many pictures of him because I don’t want to forget him when he is gone. I have no family, no wife, no kids; just a dog who listens to the radio with me on the highway, a dog with two girlfriends.

I got home at 1:00 am to Dusty shaking his tail, licking my face, smiling and winking at me, lit only by the light of the laundry machine door. The band had left up all of his party decoration out so I could see them, the streamers and ribbons and bows. It was perfect. Dusty and I curled up in bed, snuggled, and I gave him his birthday present, “Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage.” I told him. “It’s Haruki Murakami’s new book. I’ll start reading it to you in the morning.”

All of this happened, more or less, at least the parts about the dog and his girlfriends, just the way I have written it. But Dusty won’t verify my account of this. As I turned off the light he let out a sigh and placed his nose on my ankle. I had a little chest pain, and everything was quiet. “Is this all there is?” I whispered to him. And he winked.