“You know Dusty, don’t you?”

“I drew pictures at his birthday party…”

— My exchange with Aron Taylor of Austin’s Quick Draw Photo Booth

BY THE TIME the second veterinarian entered the room, I was lying on the floor and Dusty-Danger was sitting in a padded chair as if he owned the clinic. There was a splotch of smeared blood on the wall where his tail had just smacked it, when Dusty thanked the veterinarian’s assistant for scratching his ears and giving him a treat. “He is smiling at me,” the veterinarian said.

“He always smiles,” I said.

Two days before, I’d received a text message from Dusty’s dog walker as I discussed whether Silver Linings Playbook is a love story with my students. We finally determined it is, as it ends with a kiss, and that was when my phone lit up. “What’s wrong with his tail?” she messaged. “It’s bleeding.” My dog walker knows Dusty well, and rarely panics. She hosted his birthday party last summer while I was away on business. She had a singing telegram delivered to him, cooked hot dogs, and had a bone-shaped carrot cake. They made arts and crafts for the guests, and hired Aron Taylor to draw sketches of Dusty during the party. “The bump on his tail,” the message continued, “it doesn’t look good.”

Two days before, I’d received a text message from Dusty’s dog walker as I discussed whether Silver Linings Playbook is a love story with my students. We finally determined it is, as it ends with a kiss, and that was when my phone lit up. “What’s wrong with his tail?” she messaged. “It’s bleeding.” My dog walker knows Dusty well, and rarely panics. She hosted his birthday party last summer while I was away on business. She had a singing telegram delivered to him, cooked hot dogs, and had a bone-shaped carrot cake. They made arts and crafts for the guests, and hired Aron Taylor to draw sketches of Dusty during the party. “The bump on his tail,” the message continued, “it doesn’t look good.”

Dusty and I have been together for six years. He is not my first pet, but I’m picky when it comes to my companions. Looking for a dog is like looking for just the right needle in the stack of needles that is Austin, Texas, a town believed to have two hundred thousand dogs, or one dog for almost every household. I randomly found Dusty at the pound one day. An Australian Shepherd with a splash of Siberian Husky, Dusty has one blue eye, one brown eye, constantly smiles, and had a long peacock-like feathered tail that curled above his hips. When he wagged that tail the whole world knew he was happy, and if you looked him in the eye he would kiss your nose with his tongue.

I’ve never been married and I don’t have children, probably because I prefer the company of dogs, a more honest and loving animal than humans. Dusty and I go everywhere together, and his kindness trumps my skeptical sarcasm toward the world. He is the peanut butter to my jelly, the Chewbacca to my Han Solo, the Dynomutt to my Blue Falcon. Last summer we took a massive western road trip. He watched as I got a tattoo in L.A., we went graffiti hunting, gave our food money to a woman with cancer in San Francisco, and ate all the French fries Boise had to offer. Boise has become a favorite place of ours. To us the sky was big and blue in Boise, like we sank to the bottom of an ocean together. I’m not the only one taken by my dog: He has gotten fan mail from Portugal, Canada, almost all of the fifty states, and while in Boise a nine-year-old girl named Ila fell in love with him. She named her “teddy-dog” after him.

During the past year his tail had developed a knot — a knob firmly entrenched in the bone. It had been growing larger and larger, and would now often bleed as I watched. The first vet I spoke with said the knob was normal and nothing to worry about, but he changed his mind when it bled, and told me to seek a second opinion. The second vet confirmed what I feared. “This is cancer and I would like to take x-rays of his lungs to make certain it hasn’t spread,” said the second vet.

Other than writing about Dusty, my other accomplishments in life include being an Eagle Scout. Only 2 percent of Scouts earn that rank, and a Scout is always prepared. Because of this I keep a suicide note on my laptop (just in case). Dusty turned nine this year, and I knew that at some point in time I would have to say goodbye to him, but I wasn’t prepared for this news. It was a bullet to the heart. The vet suspected that whatever was causing the bump on his tail was moving fast. “I would like to amputate on Monday,” he said delicately, as I lay on the floor and Dusty smiled as he sat in his chair. Amputating was the only way to make certain, and if Dusty were to be gone I didn’t know if I’d want to go on as well. This was something I had not thought that much of. I was not prepared for this.

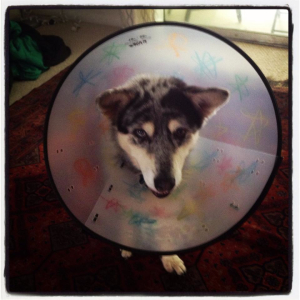

Removing Dusty’s tail to save the rest of him is like cutting toes from Muhammad Ali, or fingers from Joe Strummer: that tail is a deep part of his identity. Sorrow didn’t paint the depth of how I felt. What would be without his tail, his signature wag? The veterinarian gave me a plastic cone to fasten around Dusty’s neck, to keep him from chewing on the tumor. The cone was so drab and lifeless that I drew colorful stars all over it to brighten the mood (“Dustification,” if you will). That night I bought Dusty his favorite kind of pizza — sausage and pepperoni — and we watched The Lego Movie together. We spent the weekend hiking, snuggling, sniffing and devouring junk food as he licked my face. Sleepless in Seattle or the USC/UCLA game? I asked him. Eric, my former intern, was now in graduate school at UCLA, so we felt compelled to watch the game as a thunderstorm beat down on the roof of the house. As the Bruins pulled away from the Trojans, I researched the functionality of a dog’s tail. I wanted to know what kind of life he might have without it.

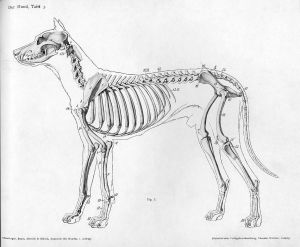

A dog has 319 bones, and can have between six and twenty-three vertebrae in the tail, depending on the breed. Dusty had twenty-three. The tail can intricately express what the dog is feeling: it’s its own form of communication. Dogs can express happiness, aggression, stress and many other emotions with their tails, not to mention what they are thinking. Wagging the tail high, and back and forth, is a sign of happiness, of feeling all right. Holding the tail horizontal to the floor is a sign of interest. A tucked tail means fear. And so on.

A dog has 319 bones, and can have between six and twenty-three vertebrae in the tail, depending on the breed. Dusty had twenty-three. The tail can intricately express what the dog is feeling: it’s its own form of communication. Dogs can express happiness, aggression, stress and many other emotions with their tails, not to mention what they are thinking. Wagging the tail high, and back and forth, is a sign of happiness, of feeling all right. Holding the tail horizontal to the floor is a sign of interest. A tucked tail means fear. And so on.

The tail has another role in communicating — to other dogs. When a dog moves its tail, it acts like a fan, and spreads the dog’s natural scent. One of a dog’s most important odors comes from the anal glands, two sacs under the tail that contain a stinky liquid that is as unique among dogs as fingerprints are to people. Cutting off Dusty’s tail would be like burning my fingerprints. Most importantly, the tail is a counterbalance to the dog’s body. If Dusty survived the surgery, he would have to learn how to walk again, without the benefit of that counterbalancing tail.

The next day, thunderstorm over, I took Dusty to the third annual “Danger Derby,” a collection of east Austin artists dropping pinewood derby cars in a hodgepodge of silliness, not unlike the toy cars Boy Scouts race down a wooden track. I told Dusty the Danger Derby was named after him. We saw many of our old friends. They all petted him, looked him in the eyes, and he gave them a lick on the nose. Our friend Linus, a kid dressed as a cowboy, lectured Dusty on the history of dog racing, and said he hoped that Dusty could race his dog someday.

Before we went to sleep that night, I looked at my suicide note again. It says little more than “I. Am. Bored.” I’ve always thought that would be the reason I would take my life, and no other. At that moment I was no longer certain, and that night I had a dream: Dusty and I were at a rural airstrip, and he curled up in a ball on the passenger seat of our truck. He turned into a young girl, maybe nine years old, put his hand on mine and said softly, “My flight’s about to depart.” We were in Boise, I think.

The next morning we got to the animal clinic a half hour early and sat in the parking lot listening to the radio. It was cold. It is never cold in Austin. Once inside, I signed a release form on what to do if Dusty passed away on the operating room table, and I began to cry as I wrapped my arms around his ribs, picked him up, and took him into the back room where they would operate on his tail.

I cannot say what happened for the next eight hours. I went to school, I think. I lectured about a southern novel, medical ethics, and romantic comedies. My phone lit up with messages from all over the world. An accordion repairman told me he lit an owl candle for my dog, and a dominatrix in Seattle said, “My thoughts are with you and Dusty.” When I went to the clinic to get him, he was not smiling, and his tail was gone. How was I to know what he was thinking? Limping and looking as if happiness itself had been beaten from him, the colorful stars I had drawn to his cone were smeared away. He put his nose against my knee to help him balance. I didn’t bother to ask what kind of anesthesia he was on. His eyes were open and that was all I needed to see.

I cannot say what happened for the next eight hours. I went to school, I think. I lectured about a southern novel, medical ethics, and romantic comedies. My phone lit up with messages from all over the world. An accordion repairman told me he lit an owl candle for my dog, and a dominatrix in Seattle said, “My thoughts are with you and Dusty.” When I went to the clinic to get him, he was not smiling, and his tail was gone. How was I to know what he was thinking? Limping and looking as if happiness itself had been beaten from him, the colorful stars I had drawn to his cone were smeared away. He put his nose against my knee to help him balance. I didn’t bother to ask what kind of anesthesia he was on. His eyes were open and that was all I needed to see.

“His tail will heal,” said the vet. “We will let you know about the rest in ten days.”

“Let’s go home. We’ll get pizza and watch football,” I whispered in Dusty’s ear.

His nub began to wag. He now had all of two vertebra in that tiny tail, according to the vet. A friend commented that Dusty didn’t need a beautiful tail to communicate. His language, his “happy wag,” was never in his tail. It all starts in his hind legs, like the way a golfer starts his swing from the feet. When Dusty gets happy, his feet press down and his butt wiggles. His tail simply follows suit. There is still plenty of happiness in his nub.

That night, as we ate pizza and watched football, I deleted my suicide note. I don’t need to be that prepared, and I’m not bored yet. “I’m going to write a new story about you. I’m going to call it The Dusty Tail,” I told him as I looked him in the eye. He licked my nose, just like the ending of Silver Linings Playbook.

Ten days later, he was learning to walk again when we got a call. The test results were back. Dusty, it turns out, is cancer free. But only hours later, just as we got pizza to celebrate, my phone lit up. The woman who we had given money to in San Francisco had passed away of her cancer. It was a quiet feeling I had. So tender, yet so happy, as Dusty smiled and wagged his hips, and his nub shook as if it was his birthday.

Even better on second reading, Tim.