Time, Part 1

IN A PRESSURIZED CABIN, sometimes you forget that there’s sky above and below, that there’s air, so much of it you can’t take it all in, right on the other side of the steel cylinder in which you’re encased. You’re cleaving the atmosphere, you’re truly amazing, but this thing could still go up in flames, like the Hindenburg. You look at old films of the Hindenburg and think, They are so fucked. And they were.

I was on a flight coming back to the U.S. from Stockholm, reading a novel on my Kindle. It was the first book I’d read on my newly-bought device, and I was still getting used to the feature that lets you see what percentage of the book you’ve read and how many minutes you have remaining to finish it.

Dept. of Speculation, by Jenny Offill, is a short book, but even so, I was struggling with the fact that it seemed to take a while to get going. At some point it needed to take hold so that I was sure to commit to the story. While sitting there in seat 30D in coach, I was able to locate exactly the point at which the story’s central event arrived: It was 54 percent of the way through. The Kindle told me so.

Time remaining: 32 minutes.

When I looked up from the Kindle I saw the monitor on the seat back in front of me, which was now indicating how long there was left of my flight to Newark: 2 hours 14 minutes. That would certainly give me plenty of time to finish the book, maybe watch a free 22-minute episode of Louie (the time was indicated for me), take a short nap, and eat my Swedish sandwich.

So I did in fact finish the book, and the momentum felt as though it picked up enormously after the author hooked me with the coalescing event. Why had she spent so long setting things up, and was I being overly critical in feeling the tension should have been greater and earlier? It’s possible the figures at the bottom of the screen were making me more conscious of this, and more impatient, than I should have been.

The book was about the various mundane facets of a marriage, and something big had to eventually transpire in the marriage to make me interested. What happened in the story when the moment finally arrived was very sad, and there in the pressurized cabin, with the beverage carts squeaking by half-heartedly in the narrow aisles, everything took on a tinge of solemn significance. I looked at all the other heads poking up above the seats. There we were, hundreds of us, hurtling through the air at 546 miles per hour. We were 34,725 feet in the air. (The monitor told me so.) What if something disastrous happened during the flight and it was the end of our remaining time?

For everyone on the flight, their time remaining would be displayed as exactly 0. Percentage of life lived: 100. The story, entirely written and read.

Offill’s book is largely about choices and the things we contend with everyday in not being able to have life exactly as we want. It’s about the gambles taken in trying to swap one existence for another, the things that are lost when trying to switch horses, as they say, in midstream. Poor us, I thought. So much ambiguity. If we suddenly had to assess everything right now while the engines failed, what percentage of us would say we’d done things right? Did we commit where we needed to commit?

In fact, we landed, taxied successfully to the gate, and all survived. Percentage of life lived: still to be determined. Time remaining: up in the air. I got the car out of long-term parking and continued home. The navigator on my phone told me exactly how long it would take to get from the airport to my house. I watched as another countdown began.

The endless numbers and percentages give an odd, nerve-wracked perspective on time, as though to suggest that every moment is accounted for. Actually, I know this isn’t true. I waste a shit ton of moments. A better feature might be for the Kindle to tell us what percentage of a book we’ve understood, or how much we may have misconstrued. But no one has invented a device to do that yet.

Percentage of life changed by reading this book: undetermined.

Painting by incessantrealism

Time, Part 2

Sometimes you miss the most important part of the story because your mind has gone elsewhere. The mind wanders like an old dog, or a lost highway. Something like that, anyway. And before you know it, someone is done with their story and there you were waiting for the heart of it and the heart came and went and passed you right by.

Old dog, lost highway. Actually, those aren’t the right images at all. If only we could go back to old dogs and lost highways. Now the mind wanders—wander isn’t even the right word, much too languid—like an electrified lab rat. It darts and pants, looking for answers, looking for rewards.

At a certain point I found myself, many evenings, watching TED talks on the laptop while doing a sped-up yoga workout on my bedroom floor. (The online yoga instructor calls it a “yoga shred.” Less time, faster results. I felt a subtle shame in taking part.) If there was a way to pack two forms of self-improvement into a half hour, after helping my child with homework and before Better Call Saul, I was going to do it. If there was a way to get the supposed distillation of some expert’s knowledge and passion in a roughly eighteen-minute presentation while they spoke into a tiny microphone affixed to their head, then I was going to reap the benefits. Let’s do this thing.

But unfortunately, night after night, I felt let down. Most of the talks I watched were simplistic and top heavy with advice, the stuff of mainstream magazine articles and pop psychology. And when I took a look at what many of the experts were doing, I saw they were, in a way, just taking apart their own work and shilling it for self-promotion. They were staying within the specified time limit and helping to spread the gospel of the TED brand.

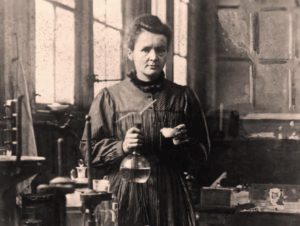

It was a strange concept, this shrunken-down motivational-speaking world. Stranger still if you time-traveled and pictured certain people taking part. Because, you see, there were certain people—most, really—who I desperately would not want to see doing a TED talk. And trying to imagine it seemed to put things in perspective. I wouldn’t want to see Henry James out there with a little microphone, or Emily Dickinson (as pithy as she was), or Marcus Aurelius, or William Shakespeare, or Marie Curie. I would not want to see Martin Luther King Jr. giving a TED talk.

Marie Curie, not giving a TED Talk.

Reader’s Digest used to sit next to toilets across America. The concept lives on. Shrink things down, carve out some message from the original source to bring the point home. But the source was so much better. It was longer for a reason. And if you’re never getting the full story, it’s possible you’re missing the best part.

At some point someone came up with memes. Someone somewhere slaps some text on an image, circulates it digitally, and this is meant to send a direct message, to instruct you, sometimes to inspire or rouse or needle you. Best-case scenario with these memes is that they remind you to read or do or listen to something you wouldn’t have otherwise. In times of social crisis, a meme can quickly make a necessary point. But most of the time memes just seem like digital-age versions of the old poster with the adorable kitten that says “Hang in there. It’s almost Friday.”

And there is the general heartbreaking shrinking of words themselves: c u 2nite. If you can’t even spell out the word “see,” how are you going to read an entire book of spelled-out words? It would be like climbing Mt. Everest with a backpack full of rocks and old typewriters.

Photo by Anton Babushkin

In an article on Medium.com, a guy named Hugh McGuire wrote about the way he found himself, over time, nearly unable to read a book. He was too busy checking email and Facebook and Twitter. “While books have always been important to me on their own (pre-digital) merits,” he wrote, “it started to occur to me that ‘learning how to read books again’ might also be a way to start weaning my mind away from this dopamine-soaked digital detritus, this meaningless wash of digital information, which would have a double benefit: I would be reading books again, and I would get my mind back.”

I wanted my mind back too. Presence of mind. This felt increasingly important. Because all over the world, people are getting shot, getting bombed, and ice caps are melting and nobody seems to fact-check anything anymore. We are so fucked. Or at least sad and mad and confused.

Can the inside of me understand the inside of you?

One day in the dreariest part of a recent winter, I took a walk at the reservoir down the road. It’s huge, this place, and where the water is, there used to be houses and towns. They flooded people’s lives out and gave them a little money to move somewhere else. I made my way over the walkway, and there weren’t many others out on such a bitter cold day. Caught up in my head, I still managed to see a bald eagle. I’d accomplished that, at least. Down below and off to the left, the reservoir was solid ice. An older man stood looking at the eagles’ nest across the way, and I stopped and we talked about this and that. He said he came there every day to see the eagles. As I turned to go, he asked me if I noticed the sounds underneath the ice. Listen, he said, as you’re making your way back.

So I did. I walked a little and stopped and stood still and he was right—there was a whole world of sound going on under there that I hadn’t noticed. Pings and sighs, pops and moans. Sometimes a short, deep pulse, then a high, singing note, as though the noise were coming from another planet. I’d say that was language of a different kind, and I was being spoken to by a trustworthy source. It made me want to give up the talks and the memes and the quotes and go subverbal, preverbal. If everything was getting so abbreviated anyway, maybe it was better to just go the whole way and stop words. Maybe if you go back to a wordless source for a while you’re eventually able to read a whole book again, unhurried. You’re able to go back to words and sentences and paragraphs, the architecture of a whole interior world. And you read them on a page made of paper and nothing to tell you the time.

~

Time, Part Now

On another day—it was spring by then—I looked up from my computer screen and saw my daughter through the window out in the yard. She was occupied with something but I wasn’t sure what. I saw a flash of color against the sky. She was throwing a clementine into the air. She took some pictures of it as it had its moment, hanging there, the orange against the blue. Clementine, aloft.

So I walked outside to get the full effect, away from the computer screen, away from the house. I could take a picture of it myself, I thought. But I was tired of doing things like that, of trying to make everything my own. We may be fucked but there’s still time. Let time have its own way. Just look up at the clementine, I told myself. Then listen to the sound it makes when it falls to the ground.

Photo by Eva Donato

Janet ! Yummy. Thank you ! Pre-verbal… let’s go! I ‘m ready to go swimming, back in there listening to sounds that Walter Murch, the sound editor from Apocalypse Now, noted we can hear in our mom’s bellies as our first sense. We can even heard the doppler effect in the womb. Take me there; where we get to just listen and then to zoom through a place of visuals to swim through. I have also been wondering in this time of memes and no fact checking that almost everyone I know has gained weight either to tether themselves down to the ground or to calm themselves. Thank you for taking us with you as we measure and refuse to measure our lives. We are now at 117 words and I am done.

Yes, we’re all gaining weight to tether ourselves! Thank you for reading…

I’m drunk but I’m pretty sure that was good.

It’s possible it’s less good if you’re sober? But thanks!

oh boy yet another reason to weep for the end of the weeklings, and thrill that I got a chance to play where the clementines drop.