WINTERS IN SYRACUSE could be beautiful. Near-constant lake effect snow and occasional, dangerous squalls gave my university campus the illusion of purity. Even when the remains of a snowfall had been trampled, plowed, and dirtied, there was always more snow to refresh the landscape.

I shared an apartment with three friends from the Syracuse University Drama Department, where I was studying theatre. We had a view of Thornden Park, a ravishing, 76-acre wilderness in a city I found depressing from the moment my family’s car turned off Interstate 81. But Thornden Park was a living Christmas card. In my first year in that apartment, the winter leading up to Christmas break was wondrous—snow everywhere and constant.

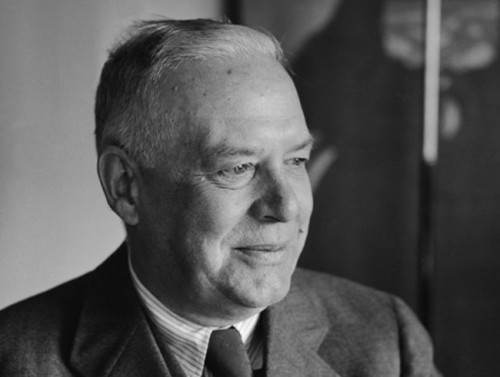

At Syracuse, in addition to drama, I studied creative writing and poetry, reading works by poets like Elizabeth Bishop, Charles Simic and Wallace Stevens. The Romantic in me gravitated toward poetry—all kinds and styles—but mid/late 20th Century poetry spoke to me. And there was something about Wallace Stevens…

American, modernist poet Wallace Stevens died in 1955 at the age of 75. Most of his great poems were written after he turned 50, when he came to be one of America’s most respected poets. He was awarded dozens of literary honors, especially in the years after 1950, capping off his success with the Pulitzer Prize just a few months before his death from cancer. An executive at an insurance company in Hartford, CT, Wallace Stevens never left his position at the firm, composing his poems on the long walks to and from his office. Where, I wondered, within a mild-mannered, politically-conservative insurance man lay the great expanse of creativity that produced such astounding poetry? From Wallace Stevens I learned evocative, precise words like “concupiscence” and “peignoir,” reinforcing my fascination with the English language.

On long walks through snowy Thornden Park I would recite poems in my head, or compose my own for the many classes I took. I could have walked for miles without a goal—only carrying the pleasure of my thoughts and bounding creativity.

On the day I returned home for Christmas break, leaving the Syracuse apartment for the first time, I was struck by the combined feelings of my longing for home and my longing for the future. When I arrived at Pompton Avenue, after the four-hour drive from Syracuse, I was greeted with somber news; my mother gently told me something bad had happened. A plane had exploded over Lockerbie, Scotland. There were Syracuse University students on board, returning from their semester abroad. No one knew how many were dead. It was assumed there were no survivors. I spent the rest of the night on the phone—in the days before mobile—calling everyone I could think of who might have some information.

It was Christmas of my junior year. December 21st. Pan Am Flight 103 has been blown up by terrorists, taking the lives of all 259 passengers and crew as well as 11 people on the ground in bucolic Lockerbie. Thirty-five of the victims were Syracuse University students: five from the Drama Department. The tragedy shook our University to its foundation.

For my big Italian-Irish family, death was always at the door. There were so many relatives—great uncles, aunts, in-laws to spare—that we had lost someone almost every year as far back as I could remember. (There was one year, some time after college, in which we lost six altogether, on both sides of the family.) But my family always managed to make it through those sorrows.

This was different. There was confusion, numbness, but what I suffered most was sympathy for my friends’ parents. And yet, my grief and fear were not as strong as they might have been. All I could think of was the horror in the air and the sorrow it brought to the survivors. I believe I have remained numb to it in the years since—allowing myself the occasional, private release of tears. But for one notable occasion, I have either dealt with it remarkably well or am living in denial. Though after so much time, I daresay I have come to accept that the world is not just. Sometimes innocent people die. The Drama Department lost five: hilarious Miriam Luby Wolfe with her silly sense of humor; Theo Cohen with her ironic point of view far beyond her years; swooningly handsome Turhan Ergin, who was everybody’s secret and not-so-secret crush; lovely, kind, talented Nicole Boulanger; and quiet, gentle Tim Cardwell.

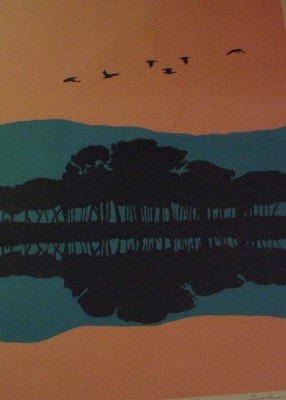

INTO THE MORNING was created by Gerardine Clark, Professor at Syracuse University Drama Department, to commemorate the lives of the 5 Drama students lost in the Pan Am 103 attack. Note the extra bird - and the lack of a reflection in the water, a detail which has always touched me.

When I went to London the following semester, agitated and apprehensive, I bonded ever closer with the friends who chose to take the semester abroad. We became a makeshift family, knowing that with our trips already booked and paid for, we were bound to the overseas semester. The opportunity would not come again. But we all longed for the collective comfort of our surviving friends back in the States.

I sought every possible thrill I could in Europe—determined to make it valuable. As London winter turned to spring and soon to a summer in the Greek isles—where I made love all day on a Mykonos beach with a blue-eyed Frenchman named Jean-Francois (I’m not making this up), I lost all apprehension about travel by air. And I returned home, ready to begin my final year at Syracuse.

The next year was wonderful and strange. We had been through a collective tragedy. We were sadder but wiser. We had become adults all too quickly and without warning. I had wanted nothing more than to remain a boy. The world was a scary place. I wondered—and I still do wonder—if I could manage in it.

This year, America is again in the throes of collective grief—once more at holiday time. The Sandy Hook massacre, like the Pan Am 103 bombing, occurring in the month of childhood anticipation and family gatherings, is like salt on a wound. John Donne said, “Death comes equally to us all, and makes us all equal when it comes,” but how random and how embittering for a loved one to be taken in a senseless act of violence.

As I grow older, the sting of nostalgia becomes more acute. It may be redundant to say that Proust hit the mark when he described his trip down Memory Lane after that madeleine; a storm of memory accompanies sensation. I find myself trying not to think about the past, trying instead to live in the moment. To stay present. To breathe and listen. Whatever those things mean. Seven years ago, in a fit of complete foolishness, I tossed away dozens of journals from my college years—trying to break with my past—including the incredibly detailed journal of my trip through Europe with my travel companion Whitney Webster and my romance with Jean-Francois. I can’t help but regret it because while nostalgia is a mixed emotion, I would like to reconnect with the teenage me and find out what he was thinking about the new.

There are, however, sensations that illuminate images in the memory. It’s difficult to isolate the particular combination of scent, sound and scene that takes me back to Syracuse winters. At least partly, the overall quiet of Syracuse must be the result of hundreds of years of sound-dampening snowfalls, where the crunch of packed flakes underfoot is quickly absorbed into the landscape. I’ve always associated winter with peace, silence and solitude, sometimes even loneliness—a caesura in the poetry of life. There is death in winter but underneath, life. Nothing and not nothing all at once. The ingredients of a precise kind of winter day recall what Wallace Stevens labeled, the “nothing that is not there.”

The Syracuse University Hall of Languages. In the far, right background, mostly hidden by trees, is Crouse College of Visual and Performing Arts. Photo: David Lassman

That time in my life when I would ponder life’s mysteries is long gone – that time when I embraced the emotional turbulence that led to mature awareness – but long walks through winters at Thornden Park live forever in Stevens’ “The Snow Man” as well as the burden of Pan Am 103. Stevens’ mind of winter is the knowledge of the death that winter brings and the rebirth it promises. In the shortest days of the year, we live for months with the evergreens reminding us that even in the “dead of winter” there is life.

One must have a mind of winter

To regard the frost and the boughs

Of the pine-trees crusted with snow;And have been cold a long time

To behold the junipers shagged with ice,

The spruces rough in the distant glitterOf the January sun; and not to think

Of any misery in the sound of the wind,

In the sound of a few leaves,Which is the sound of the land

Full of the same wind

That is blowing in the same bare placeFor the listener, who listens in the snow,

And, nothing himself, beholds

Nothing that is not there and the nothing that is.

~~~~~ Wallace Stevens, “The Snow Man”

What a beautiful tribute to the present, the past, and the future.

So lovely, Tom. Your descriptions of Miriam, Theo, Turhan, Nicole, and Tim are exactly as I remember them. I could not look, could not read anything related to Pan Am 103 for such a long time–I know, in my case, it was denial, not coping. It took 20 years for that winter to begin to thaw, for me to face the photos and the tributes. Thank you for your words, imbued with connection and with heart. When all things fall away, and memories fade, our connectedness remains.

Thank you for reading, Alicia. I’m so glad you are able to look back now. Grief never ends but it does ease over time. Twenty years seems to have flown by and yet – it feels a lifetime ago.

Thanks Tom,

Beautiful, it’s good to remember and nice to see though your eyes.

Tom, that was very touching and beautiful. Hugs.

I love you, Tom.