i.

IN MARCH OF 2011, I was on a panel with three other novelists at the Quais du Polar literary festival in Lyon, France. We were there, if memory serves, to talk about strong female protagonists in crime fiction, but the discussion wound up encompassing much more than that. At one point, we were asked about the utility of the novel. In a century of smart phones and dumb tweets, with attention spans shorter than ever, what possible purpose could such an analog medium serve?

I had no ready answer for such an existential question. Fortunately, the French novelist Sylvie Granotier was prepared. It is exactly the analog nature of the form that makes the novel so necessary, she said. In a world of ADHD, she explained—in English as fluent as my French was not—the novel, alone among the art forms, demanded more, not less, attention from its readers. Only the novel could combat the erosion of our collective ability to focus. And it did this by insisting that its readers move at the deliberate pace set by the novelist.

“The power of the novel,” she said, “lies in its ability to stop time.”

ii.

In his column in The Believer some years ago, Nick Hornby wrote in praise of the short novel—the work of fiction that, as he put it, if you start reading when the plane taxis along the runway at LAX, you will be just wrapping up as the wheels hit the tarmac at JFK. His novels all meet this criteria. So do mine. Indeed, the lion’s share of fiction churned out by the big publishing houses seems to be written with the sole purpose of amusing the bored business traveler.

It is interesting that Hornby chooses the duration of a transcontinental flight as his fiction-reading threshold. In flight, our smartphones must be set to airplane mode, and this is the only time when we are not free to text, tweet, check our e-mail, scour the Facebook feed, or post pictures to Instagram. In order to be truly “unplugged” in our technophiliac age, we must be in a 747 at a cruising altitude of 30,000 feet. Our Emersonian cabin in the woods is a cabin in the sky.

The other reading venue heavily promoted by publishing houses is the seashore. “The perfect beach read,” many a capsule review will announce of a novel, the implication being that only at those moments when sand and surf prevent use of our handheld electronic gadgetry will we deign to glance at something printed on paper. “Beach read” is a white towel of surrender, an admission that a novel can never compete with the myriad forms of more interactive entertainment now on offer.

Airplanes, beaches, and the third novel-reading locale is even less distinguished: the bathroom. I recall a post on The Nervous Breakdown a few years back, in which Brad Listi—whose novel is titled, significantly, Attention. Deficit. Disorder.—suggested that the toilet was the last bastion of the reader of novels. Commentators chimed in, revealing which works of fiction they had consumed in the can.

Restroom reading works for High Fidelity and About a Boy. It works for Attention. Deficit. Disorder., and both of my books, and pretty much anything you can buy at a supermarket: the entire output of Nicholas Sparks, Steve Martini, James Patterson, Patricia Cornwall, etc. But other books, better books, demand more from us. Unless one suffers from a particularly virulent strain of irritable bowel syndrome, one cannot consume The Savage Detectives while defecating.

This is not a criticism of our collective reading habits, but rather a survey. I read more than many, but I’m just as guilty as anyone of eschewing serious reading for the less demanding pleasures of the Instagram feed. The point is that, with the rise of technology, the novel has become a marginal art form—not as marginal as ballet or opera, but less relevant to the popular culture than television drama or video game. When a novel does manage to force its way into said popular culture, it is invariably something like 50 Shades of Grey or The DaVinci Code—books that should not be read on the toilet, as much as kept nearby in case the Charmin runs out.

iii.

The key to the survival of a new social medium is critical mass. Once enough friends, family, and various and sundry public figures take to a new medium, and use it regularly, it becomes indispensable. Thus Facebook succeeds where Ello fails.

Critical mass is what makes social media so much fun. I can scroll through Instagram, for example, and see images from, in order: my wife, one of my writer friends, someone I know vaguely from high school, Lindsay Lohan, a Weeklings co-editor, a former student of mine, Emma Slater from Dancing with the Stars, and George W. Bush [1. Dubya’s Instagram feed fascinates me]. Twitter is even quicker, and more variable. The feed moves at astonishing speed, with updates from many different kinds of people, listed in the order in which they were posted. That means my brain has to organize them all very quickly: Who is this person? Do I care about them? What category or categories does he or she belong to? My mind is like one of those cartoons where dishes keep falling off a shelf, and I try to catch them all without breaking anything.

Do this enough, and it re-trains your brain to work in a different way. It begins to influence, and even to alter, the very way you think. And if you happen to be a young person who grew up on Twitter and Facebook, it’s already done so. You already think differently than your parents do.

iv.

The Earth moves in three different ways. Two of these motions are obvious, because rotation and revolution are how our basic units of time—day and year—are derived. The four seasons, another unit of time measurement, are caused by the interplay between rotation and revolution.

But there is a third motion to the planet, one that takes far longer than the other two: the wobble. Ever spun a top and observed how its top wobbles as the body spins? The Earth does the same thing—slowly, very slowly, but ineluctably. It takes one day for the Earth to rotate on its axis, one year to revolve around the Sun, and a whopping 25,868 years (give or take) to wobble around completely. One 360-degree wobble is called a Great Sidereal Year—or, more frequently, a Platonic Year (PY).

Now, imagine that you’re up in space, staring down at the North Pole. Also imagine that some celestial cinematographer recorded the Earth making a full wobble in time-lapse photography. What you would see is a point moving in a circle—like the tip of the second hand on a clock, except wicked slow. Let’s give this circle of completed wobble a name. Let’s call it Dave. There are 360 degrees to Dave. We mark these degrees in units of twelve—just like we do on a clock. But instead of numbers, we use the zodiac—a series of “fixed” stars near the equator, visible from both hemispheres, by which we track the motion of the Earth. Continuing our clock analogy, then 1 is Aries, 2 is Taurus, 3 is Gemini, and so on, to 12, which is Pisces. Each of these twelve divisions of the Platonic Year—a Platonic Month, if you will—is called an Astrological Age.

One more thing: the Earth wobbles backwards through the zodiac. So Dave is moving in reverse. Instead of going from Aries to Taurus, Dave travels from Aries to Pisces, and from Pisces to—mirabile dictu—Aquarius. Right now, the consensus is that we are in the Age of Pisces. It has been the Age of Pisces for a really long time. We’re waiting for Dave to break the plane of the 11—and for Earth to enter the Age of Aquarius.

In the popular culture, the Age of Aquarius is presented as a time of universal love. Harmony and understanding, sympathy and trust abounding / No more falsehoods or derisions / Golden living dreams of visions / Mystic crystal revelation / And the mind’s true liberation, as the Hair lyrics put it. Indeed, the very term “New Age,” with all the healy-feeliness it implies, derives from this: the Age of Aquarius is the New Age.

Unfortunately, James Rado and Gerome Ragni, who wrote the book and lyrics for Hair, have a remedial understanding of astrology. When the moon is in the Seventh House /And Jupiter aligns with Mars sounds boss, but astrologically it makes no sense. We’re not told which horoscope features the moon in the Seventh House, and “aligns” does not indicate if Jupiter and Mars are conjunct, trine, square, or in opposition. Worse, they have misrepresented the spirit of Aquarius, and what its Age might mean. “If the coming age is really Aquarian,” writes the eminent astrologer Robert Hand in his indispensable Horoscope Symbols, “it may be an era in which individual considerations, emotional ties of love, and bonds of tradition are ruthlessly rooted out in favor of various utopian orders that are conceived entirely in the head and not at all in the heart.”

Aquarius is the third of three air signs, more cerebral than emotional, more communal than individualistic. “Aquarius is the sign of the individual as a cooperative unit of the group,” says Hand. “Aquarians tend to have strong social ideas about who people ought to be, but they do not relate easily to individual people except perhaps insofar as they embody social issues. Aquarius is the sign of the humanitarian who loves all mankind but no individual human being….Aquarians are more at home with friendship than with love.”

Horoscope Symbols was published in 1981. Given the rapid-fire way that air signs communicate, and their sacrifice of depth for breadth of knowledge, Hand may well revise that last sentence now to: “Aquarians are more at home with Facebook friendship than with love.” Thirty-four years ago, Hand could not have foreseen the coming of Twitter and Reddit, of Tumblr and Tinder, but there is nothing in the world, nothing at all, so Aquarian as social media.

The Age of Aquarius began, it says here, on February 4, 2004—the day Facebook was launched.

v.

Websites now cater to this frenzied, Aquarian type of thinking. We no longer read essays composed by writers. We read content compiled by content creators. In my Facebook feed the other day, I came across a link to a piece (an article? an essay? no: a piece of content) that purported to be a list of the dozen or so best cop shows of all time. The parenthetical title was “And No, The Wire is Not Number One.” Given that The Wire is widely regraded as the best TV show of all time, it is certainly the best cop show of all time; the piece’s title is the small-screen equivalent of “The 12 Best Chicago Bulls Shooting Guards of All Time (And No, Michael Jordan is Not Number One).” The motivation here is shameless: they want us to read the piece of content to find out which show could possibly usurp The Wire atop the leader board. Click-bait, this is called. A sizable percentage of pieces in any Facebook or Twitter feed comprise this sort of thing. Sites like Buzzfeed and Thrillist have amassed fortunes catering to our collective need for it.

Although I did not read that particular piece, I am not immune to the lure of click-bait content. I too want to know which celebrities are shorter than we think, which performers are banned from Saturday Night Live, which are the most drug-addled albums of all time. I’m not above creating this sort of content myself. (See what I just did there? I put in a link that I’m baiting you to click on.) Indeed, the most popular posts here at The Weeklings are all Top 50 lists. And while we pride ourselves on the length and breadth of our lists—it is a Herculean labor to write something like this—we are only doing a fancier version of what Buzzfeed does. As a writer, it affects the way I decide what to write about. A few months ago, I was in a terrible rut, obsessed with our traffic, and all I could think about was what would make a good Top 50 list. Every piece of information that came at me, my brain tried to organize into a Top 50 list.

The task of creating content now influences how I look at the world.

vi.

Nine years before the web browser was invented, there was already movement in the Aquarian direction. In 1982, USA Today began publication, a newspaper with no “jumps,” that distilled news stories to short, easy-to-read paragraphs, and differentiated its sections with bright colors. By 1985, it was the second-largest newspaper in the United States. The message was clear: make it short and to the point, because we all have better things to do than sit around reading. Thirty years later, the few newspapers that survive do so on smaller budgets than ever before, filling pages with syndicated columns, wire stories, and local pieces about health, sports, and entertainment. Investigative journalism has gone down the drain with the bathwater.

Chris Hughes, Mark Zuckerberg’s Harvard roommate and thus an original investor in Facebook, spent some of his vast fortune acquiring The New Republic, the venerable liberal magazine given to publishing interminable pieces on political policy, only to refashion it as a vaguely liberal, political Buzzfeed. Dana Milbank of the Washington Post was one of many columnists to slam Hughes, calling him “a dilettante and a fraud,” but maybe the 31-year-old new owner, member of a generation that gets its news from The Daily Show, is simply more in tune with the Aquarian manner of thinking. In the age of Twitter, TNR is a dinosaur, and it needs to adapt or die.

vii.

Aquarian thinking is not, it should be said, inherently bad (or malefic, to borrow a word from the lexicon of astrology). But it is very different. And adjusting to the new mode, for those of us who grew up with newspapers and novels and network TV, can be painful. We all have moments, don’t we, when we want to delete our Facebook account, get off Twitter, smash our iPhones with a hammer, and enjoy the silence.

Some of us have done just that. The humorist Whitney Collins did an experiment over the summer on these pages, in which she “unplugged.” For ten weeks, she lived without screens of any kind. No computer, no TV, no smartphone, no Kindle Fire. After an initial period of shock, she was able to slow down and move to her natural rhythm, rather than march to the beat of the Facebook drummer. “I learned that, for me, Facebook is not so much distraction as drug,” she wrote in her last dispatch of the summer. And yet she also recognized that without Facebook, without email, without texting, she did miss stuff, most of it superfluous and silly, but some of it potentially useful and necessary. And there is the rub: how to get what we need out of social media, without giving ourselves over totally to the Aquarian mindset? How do we slow down?

A year or so ago, I was suffering from Facebook fatigue. I needed a respite from Aquarian thinking. My intuition told me to start reading Proust. I have this lovely edition of Swann’s Way, an oversized paperback with deckle edges and a gorgeous shiny two-toned cover—the sort of book that practically begs you to read it. So that’s what I did. I turned off my laptop and dug into Swann’s Way. Have you ever read Proust? It’s like having a dull dream from which you can’t awaken. You just meander along, remembering a madeleine cookie here, a spinster aunt there, and the next thing you know, you are in Proust’s head, moving at Proust’s desultory pace, and Twitter is far, far away. And lo, my Facebook fatigue was cured. Incidentally, I found Swann’s Way incredibly dull. But I think that’s a key part of its efficacy. The antidote for the frenzy of social media involves more than a trace amount of boredom.

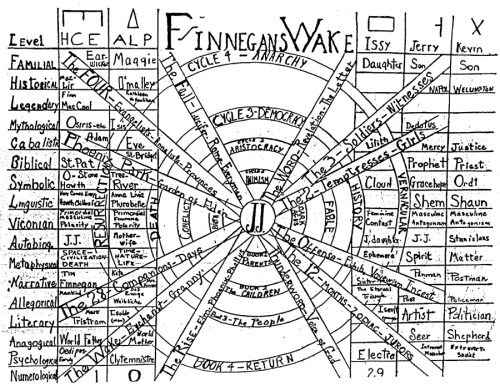

This, I think, is what Sylvie Granotier was hinting at with her declaration that the power of the novel lies in its ability to stop time. A novel—a literary novel, not something that is essentially a film treatment in book form—breaks down our resistance, wrests us to its own pace, and forces us to slow down. By doing so, it releases us from the relentless engine of Aquarian information processing, which dictates that we plow through as much material as we can, as quickly as we can, and then move immediately to the next thing. Only the novel has the power to do this. Poems and short stories are not long enough, and films, TV shows, plays, and all kinds of music play for a more or less constant and finite length of time. But it might take weeks to read Infinite Jest or 2666 or The Kindly Ones. It might take months. You don’t know until you start reading. As Joyce said of Finnegan’s Wake: “It took me 18 years to write it, and it should take you 18 years to read it.”

After 18 years of Finnegan’s Wake, you’ll feel better about logging back on to Goodreads and awarding it five stars.

Good one, Mr. Olear. Smells like Tome Spirit.

As I read this fine, thoughtful essay, I find myself ruminating about the novel as the essential key to knowing what it means to be one human being among others. But as an eighty-plus veteran novel reader, I still cling to the biggies as my reference point to that literary term: the Homeric epics, which are novels in verse; War and Peace, Bleak House, Fenimore Cooper’s Leatherstocking tales, Moby Dick, Vanity Fair, Les Miserables. Still mindful of how a great novel can transport an avid reader into another social world and provide a new perspective for the engaged self, I now wonder what we are abandoning with our neglect of the prolonged, serious read (humor can be serious, too. Look at Cervantes and Henry Fielding). New York to LAX does not allow enough time; the beach is the wrong place to visit a novel. It’s as if Alice spent a scarcely a minute down in the rabbit hole, or Huck Finn crossed the Mississippi on the I-70 bridge at St. Louis alone instead of rafting downriver with Jim.

I love Facebook, and in fact I find myself experimenting with it as a new outlet for the serious short essay, thinking in my self-absorbed vanity as some digital counterpart to Francis Bacon. But that’s precisely the problem; I remain self-absorbed, looking inward rather than wide eyed at Captain Ahab, David Copperfield, or Anna Karenina. When it comes to literary experience, a cross continental flight is no substitute for a real journey; the beach is not really a worthy place to sit and read. Give me Marlow’s river adventure or the Lake Country of Wordsworth’s childhood in The Prelude, which I consider a unique, novel-like autobiography in blank verse.

Nope. We’ve lost something in our turning away from the rich, lengthy novel and its non-fiction counterparts. And it may be everybody’s loss, not just our own. I listen to fools like Ted Cruz and watch soulless leaders like Mitch McConnell flounder as they conflate leadership with the seizure of raw power, and wonder. Have they ever drenched themselves in Proust? Shipped out on the Pequod? Fled through Paris sewers of Paris to escape the clutches of Javert? For that matter, have they self-examined the way that obsessive, misguided avenger did? What novels have the Koch brothers read? What windmills are they tilting at?

But then this digital world is no longer mine; my age is not the Aquarian one. What do I know other than the coming of age of Tom Jones? A long time teacher, I’ve apparently run out of students. Or are today’s students running out of teachers? Commiserating a few weeks ago with a fellow octogenarian about such matters, I pondered soberly as he observed he was glad to be at the age where he’d soon be checking out. Maybe it’s that way with me as well, but that’s okay. I’ve had a great life, guided largely by the great novels I’ve read, and an occasional non fiction classic as well, like Paradise Lost or The Education of Henry Adams. And God willing I make it to the coming summer, I’m planning on reading Gibbon at last. I’ve put it off long enough.

I learned astrology later in life. I decided to try to make sense of the Age of Aquarius song lyrics that seemed so mystical to me as a younger person. However, since learning astrology, I’ve found disappointment in that the lyrics make no astrological sense and it appears that neither authors of HAIR, where the song first appeared, knew anything about astrology either. I find it laughable to watch modern day church choirs sing “When the Moon is in the 7th house”… on You Tube without a clue what they are singing about.

There is this strange hypocrisy in America about astrology. On the one hand, people shy away from it in conversations saying, “You don’t believe in astrology do you?”, but on the other hand, they do sense its mystical attraction, so they allow it in song lyrics, just as long as it does not get too close to home in real life events or relationship situations. If you read bios of James Rado and Gerome Ragni, Broadway actors who wrote Hair, there is nothing in them about their knowledge or interest in astrology. What we do find is that they had enough conviction about it to have an astrologer on their production staff of Hair and she decided the opening date for their Broadway premiere to be April 29, 1968 because she found it to be an auspicious date. Apparently she was right. Her name was Marie Crummere and she had an astrology practice at East 71st Street, New York. She was even astrologer to Montgomery Clift at one point. She also authored several astrology books in the 1970s, including Age of Aquarius (1970). However, in looking into it a bit I find Gerome Ragni’s chart does have “moon in the 7th house” and “Jupiter aligns with Mars” in Scorpio, so there may just be something to it–it was his chart. Unfortunately, this is just speculation until we get some more information about how those lyrics wound up in the song.

It may be true that modern social media like Facebook are indicators that the Age of Aquarius is upon us in that they are connecting humanity–just as long as they are not close–which is one of Aquarius descriptions. I think another is this modern fascination with robots and the technology worship of modern times. I think it likely that 50 years from now people will be wishing all this robotization would go away and things could be more natural as they used to be.