CHICK LIT MAY have peaked and the 90s long gone, but the genre’s identifying characteristics are still around: the cutesy covers, wisecracking characters, designer shoes and cocktails, wacky dating scenarios, hot sex/no sex vs. love and marriage, single women with dream jobs, and, never you forget it, affluence. The black women I know who buy books and attend book clubs adore black chick lit. Yet, here I am, a writer of black literary fiction, knowing that many of my friends and relatives may buy but actually dislike my work.

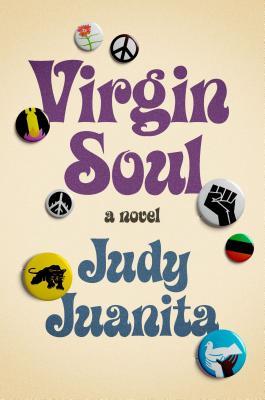

The black or ethnic chick lit phenomenon, heralded by Terry McMillan’s Waiting to Exhale in 1992, led to new genres, including urban fiction, street lit, or gangsta fiction, which came to overshadow African-American literary fiction. The new genres have box office clout. A black female writer not writing chick lit has an uphill challenge. The proliferation of largely female black book clubs ensures that these novels are instructing a significant part of the black reading community and even the publishing industry at large. Viking, the publisher of my novel, Virgin Soul, due out in April 2013, mailed me the cover recently. My first thought: it was cartoonish. Rebecca Vnuk, writing in Library Journal characterized Hen Lit or Matron Lit as women’s fiction “marketed with cutesy covers to capitalize on the chick lit trend.” Oh, no, I fell back into a ghetto?

It’s ironic that black chick lit, street lit and urban fiction for a time represented the whole of contemporary black literature. Henry Louis Gates Jr. in Langston Hughes, Critical Perspectives Past and Present, said Hughes constructed “an entire literary tradition upon the actual spoken language of the black working and rural classes—the same vernacular language that the growing and mobile black middle classes considered embarrassing and demeaning.” The confining now-popular genres use selective pieces of this “actual spoken language,” which accounts for its colorful appeal. But the work often treats complexity and individuality elliptically. Yet these books are the fashion. When I went to visit a relative in the county jail and asked how he was faring, he replied that he had found a book by Omar Tyree and (thus by connection) jail wasn’t all bad. Yet, in a live interview, even McMillan expressed disapproval of her progeny :

There are a lot of fine young new African-American writers out here. [But] I am not a fan of ghetto and urban lit…. I take seriously what they’re writing about in terms of inner city life and all that. But I don’t like the way that they tell their stories. It’s not very redeeming. It seems that they glorify violence and hatred and self-hatred to me, to be very honest. And sex is gratuitous. I don’t like the exploitation of black women’s bodies on the covers of all the books that they use to sell them. And to me a lot of them are poorly written and unedited. And I think as black people we’ve struggled too long and too hard to try to be decent people and treat each other with a lot more respect and dignity. And these books just fall so short of it. It’s almost as if they [the authors] don’t even believe that we deserve it.

Black literature, which I first devoured in the 60s/70s, included African-American speech in the urban zones. There was Adrienne Kennedy writing “The Funnyhouse of the Negro,” the beat poetry of Bob Kaufman, the black nationalist ravings of Amiri Baraka, Ba’hai-influenced poetry of Robert Hayden, the chants of Sterling Brown, Gwendolyn Brooks’ window on Chicago in poetry, and yes, Iceberg Slim’s pimps. We were universal. There was no disconnecting Aimé Cesaire and Wole Soyinka’s work and Claude Brown’s Manchild in the Promised Land. We were/are part of a diaspora and the whole of our literature isn’t a trend. Yet it would be dangerous to discount literature that comes from the street.

The Irish have struggled with this exact conundrum and their place in world literature for centuries now. Irish poet, scholar, folklorist and onetime president of Ireland, Douglas Hyde, in 1892 (yep, 120 years ago), in Irish Literature: A Reader, wrote: “[In] Anglicising ourselves wholesale we have thrown away with a light heart the best claim which we have upon the world’s recognition of us as a separate nationality.” He conflates Anglicization with “the loss of our language.” But he protests that Gaelic poets and scribes are invaluable and “Irish language is worth knowing, or why would the greatest philologists of Germany, France, and Italy be emulously studying it, and it does possess a literature, or why would a German savant have made the calculation that the books written in Irish between the eleventh and seventeenth centuries, and still extant, would fill a thousand octavo volumes.”

The Irish and the African-American in their respective Western societies have been oppressed, outcast, troubled, disenfranchised. It’s natural that their literature would feature the characters that New Zealand blogger Emily Temple in “10 of the Greatest Underdogs in Literature,” labeled “the poor, the failing, and the unlikely to succeed.” Being the underdog gives a sort of bragging right, automatic street cred, an authenticity. The problem is when it’s only braggadocio and in your face, when it struts for struts’ sake. I asked my son, grandson and my grandson’s mother to dinner recently. I asked her to think about my book for her book club to which my son said, “Don’t even try it, Mom. Her book club reads the man-hating, preachers-cheating-on-their-wives, cheesy ghetto erotica.” We all had a good laugh, but she agreed with him as she thumbed through the galleys of Virgin Soul. I hate to be discounted.

I would never discount Sister Souljah’s The Coldest Winter Ever. I stayed up all night reading that debut novel from a Rutgers and Cornell alumna cover to cover. Thoroughly hip-hop, it gave me chills. Rosa Lee: a mother and her family in urban America by Leon Dash and Makes Me Wanna Holler by Nathan McCall are as gritty, provocative, urban and in-your-face as any street fiction, yet they are more enlightening because they delve deeper. James MacBride’s Color of Water and, from Ireland via Brooklyn, Frank McCourt’s Angela’s Ashes strip poverty to its naked truth and, in doing so, illuminate the human condition. I want grit. I don’t want to be trapped and unable to escape it.

I made a list of the categories Virgin Soul falls in and came up with nine: coming-of-age, black lit, black politics, sixties, feminist, chick lit, radical lit, college novels, and literary fiction. Maybe the book won’t be ghettoized, just split into a myriad of classification. And on second glance my cover didn’t look so cartoonish. It featured an array of sixties-type protest buttons, including a Muslim crescent moon and star. A friend looking at it asked if I had written about the Prophet Muhammad. I had not, though there are scenes with Black Muslims. Apparently somebody thought twice about that one button. It was replaced with a War Is Not Healthy flower pin. (Thanks, Viking, I don’t need a fatwa on top of everything else).

A writer friend, on hearing of my book sale, welcomed me to “the publishing house meat grinder.” Between that grinder and finding where I fit with the reading public not to mention my own reading relatives, I feel my innate scrappiness rising like sap to meet all challenges and to come out whole regardless.