The recent explosion in New York’s Harlem was followed by a disturbingly familiar litany: the dead, the missing, the shellshocked dozens who improbably walked away. Debris littered the nearby Metro North tracks. Glass from shattered windows covered sidewalks in the vicinity of the blast site. Two brick buildings had crumbled as easily as desiccated sandcastles before a tsunami.

Within minutes my phone lit up with emails and texts. To my friends, I’m the bomb guy, the guy writing the “bomb books.” Did I hear? An explosion! In Manhattan!!

The T word, unspoken, hovered on the tip of everyone’s tongue.

That presumption had formed in an instant — beginning in people’s minds but quickly transmitted with wide eyes across coffee carts and, more subtly, in the urgent voices of newscasters: That a Manhattan explosion must mean a bomb. How could it be anything else? Maybe the terrorists meant to do it or maybe they blew themselves up in the planning. Both of those events have happened in New York history, and more than once.

Statistically, which is to say intellectually, we should know better. We should know that a gas leak will provide the more likely explanation of any building explosion. But this isn’t an intellectual exercise for the average citizen. It’s emotional, something we fret about, much as nerves visit us when we board a plane even while we ought to understand that commercial airliners are safer than cars.

The counterpoint to that analysis penetrates our rationality: Boom! Bomb! Boom! The onomatopoetic root of the word speaks to the fact that bombs hit us not in the head but in the viscera. And that is quite literally so.

The detonation of a bomb first produces a blast wave consisting of highly compressed air that travels faster than the speed of sound, followed by a shock wave that forces energy through nearby matter. If you’re close enough to the seat of the explosion, that matter includes your flesh and bone. Even a bomb suit — ninety pounds of kevlar — offers only limited protection.

A bomb technician once told me the story of a Russian cop who found a device placed in a corner where two buildings came together. The Russian calculated its size and figured the bomb suit he wore would protect him in the event of an accident, but he forgot to figure for the amplification effect of the two buildings. When his “render safe procedure” failed and the bomb detonated, the blast-shock combination rendered his insides to jelly, never mind the ball bearings packed around the charge.

There’s something macabre about what a bomb does to humans and their surroundings. In less than a second it can reduce our most ambitious edifices to dust while disfiguring the gifts that nature bestowed upon us, the integrity of our own bodies.

Perhaps those are among the traits that most inspire the twisted minds of bomb makers. In fact, the first group to consistently terrorize New Yorkers with bomb violence — an organized crime group that came to be known as the Black Hand for the symbolism imprinted on its extortion letters — initially had a fondness for kidnapping children for ransom and sending the horrified parents severed ears or fingers if payment didn’t arrive quickly enough. Is it any wonder that people who commit such atrocities would soon “improve” their technique by planting dynamite bombs instead?

We tend to think of our times as uniquely challenging, which they are to some extent. For sure, planes turned into jet-fueled missiles on 9/11 may prove to have been a symbol of our age beyond compare. But in the broader sense we are much safer than ever. Steven Pinker powerfully observed in The Better Angels of Our Nature that violence worldwide, at least when measured per capita, has declined dramatically over the arc of human history and continues to do so.

In New York City, evidence bears this out. Threats remain, of course (I should know; I’m basing fiction upon them), but it’s calmer now. By contrast, in the first two decades of the Twentieth Century, New Yorkers daily faced bombing violence motivated by extortion, foreign sabotage and terrorism. Around the turn of that century, hundreds of bombs appeared every year in Manhattan. In an article written in September 1905, the New York Tribune claimed that bombs confronted “the nervous citizen of Gotham” 400 times per annum.

Running up the score in those early years was the aforementioned Black Hand. Having followed a surge of Italian immigrants across the pond, this outfit practiced basic protection rackets targeting ordinary workingmen who had begun to prosper. When they weren’t kidnapping children, Black Handers threatened to blow up business establishments unless the owners forked over big money.

Modern law-and-order types who rightly worry about the scourge of illegal drugs or street gangs might consider the level of comparative impunity with which criminals behaved a hundred years ago. For example, the Morello Gang, New York’s first Mafia family, not only used murder as a regular means of intimidation, but brazenly stuffed their victims into barrels and dropped them on the doorsteps of their enemies.

The most egregious threat, however, came from a stick of dynamite.

Newly successful immigrant tradesmen commonly purchased tenement buildings, where they could rent out rooms to less prosperous boarders. But too often the new landlords then received notes demanding protection money, those notes imprinted in black ink with the image of a hand holding a stiletto.

The Black Hand didn’t do idle threats. One man named Salvatore Spinelli had started as a house painter, saved his money and purchased a pair of buildings on East Eleventh Street. When the Black Hand came calling, Spinelli told them “to go to hell.” Instead they employed what newspapers of the day dubbed “infernal machines.” Five of them, to be precise, driving away all but a few of Spinelli’s tenants. (Those who stayed must have had no alternatives.) Near ruin, in 1908 he took to futile pleading with a letter to the New York Times, which is how we know his story.

Most victims of this racket remain anonymous, but no one was immune. The famous tenor Enrico Caruso received a letter with a demand for $2,000 and promptly paid it. Only when the extortion escalated beyond all reason did he turn to the police.

Pasquale Pati, the most successful Italian-American banker of his day, attempted to resist from the start. The Black Hand promptly blew the facade off his establishment on Elizabeth Street with a dynamite bomb, causing no casualties but instigating a run on the bank that forced it to close.

An explosive device launches matter toward entropy, and in the hands of bad players it likewise threatens social disorder.

By the turn of the century, New York already knew it had a problem. In 1903, the NYPD’s Italian Squad, progenitor to the Bomb Squad, began operating under the leadership of Lieutenant Joseph Petrosino, the highest-ranking Italian-American on the police force. As the three anecdotes above attest, his first efforts were slow going. On May 26, 1908, theEvening World ran a front-page article ripping into Petrosino and “his special Italian staff,” calling them a “failure.”

Eager to stem the violence, in 1909 Petrosino traveled to Palermo, Italy, in an attempt to gather information that he hoped would lead to the deportation of several Black Hand operators. Instead, someone set him up, and he was gunned down in a piazza on March 12, becoming (to this day) the only New York City cop ever to die abroad in the line of duty.

Although Petrosino is worshipped by modern law enforcement types for his efforts — especially by Italian-Americans — Black Hand dynamite bombings didn’t really tail off until a few years after his death, when the new commander of the Bomb Squad, Thomas J. Tunney, discovered and arrested the ringleaders and their bomb makers.

But New York still trembled under bomb threat, this time from political terrorists — mostly anarchists — and German saboteurs.

The efforts of these two distinct groups culminated in a pair of events that in their day were as unexpected and dramatic as the worst plots that Al Qaeda has perpetrated upon modern Americans, with the exception of the unprecedented destruction of life and property during September 11, 2001.

The first of these events occurred before the United States entered World War I, but after we’d already embarked on an effort to supply the Allies with munitions. New York and other cities swarmed with German spies. The State Department expelled Franz von Papen, the German military attaché in Washington, for espionage after papers in his possession revealed “a nationwide plot, from New York to San Francisco, to blow up bridges and tunnels,” according to Military History magazine. (Papen, whose patriotism apparently knew no bounds, later briefly served as vice chancellor to Adolph Hitler.)

Most military supplies intended for France and England shipped from New York Harbor, so the waterfront became the locus of efforts to disrupt this trade, and the saboteurs did so however they could. Time bombs snuck into bags of sugar exploded on dozens of ships bound for the Allies, and Tunney’s men disrupted a plot to rig bombs to ship rudders — designed to detonate after so many rotations like a grandfather clock cranking to midnight. A German immigrant named Erich Muenter (alias Frank Holt) detonated a bomb in our nation’s Capitol building (causing massive damage but no casualties, as Congress was not in session), boarded a train for New York, and visited J.P. Morgan’s house on Long Island the next day with a suitcase full of dynamite. Before he could be beaten into submission by the butler, he managed to shoot Morgan (not fatally), and he was later discovered to have already shipped a bomb that would explode days later on one of the financier’s ships, the Minnehaha. But all of this activity was the appetizer.

Early on the morning of July 30, 1916, a huge explosion occurred on Black Tom Island, a spit of land near Liberty Island in Jersey City. Three-quarters of all ammunition manufactured in America shipped through Black Tom, and at the time two million pounds of it was sitting at the railroad depot there, including a hundred thousand pounds of TNT. Residents as far away as Philadelphia and Maryland felt the force of the explosion, which shattered countless windows in lower Manhattan, damaged the Statue of Liberty, caused the evacuation of Ellis Island, and sent engineers scrambling to check the structural integrity of the Brooklyn Bridge on the opposite side of Manhattan. The explosion and resulting fire destroyed six piers, thirteen warehouses, and dozens of railcars. Compared to that level of property destruction, the human toll proved mercifully light — five to seven people killed, probably thanks to the early hour of the morning — but including an infant a mile away who was thrown from his crib by the force of the blast.

Four years later, the anarchists had their turn. They had already been making their mark, setting off bombs by churches and government buildings, at the private home on East 61st Street of Judge Charles C. Nott of the Court of General Sessions, and in the north aisle of St. Patrick’s Cathedral. On July 4, 1914, three anarchists constructing a bomb they intended to deliver to the home of John D. Rockefeller in Tarrytown inadvertently blew themselves to pieces (and killed an innocent person, as well as injuring 20 others) and destroyed a tenement building on Lexington Avenue.

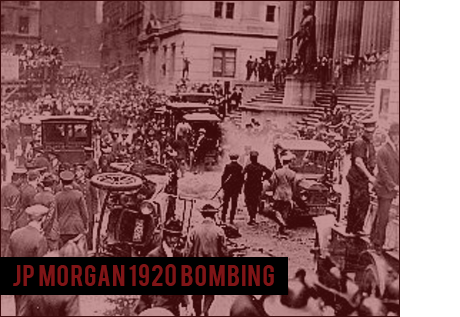

On September 16, 1920, the toll ran much higher. At noon that day a horse-drawn single-top wagon with red running gear pulled to a stop among lunchtime crowds at the corner of Wall Street and Broad, across from the J.P. Morgan building. Like September 11, 2001, it was a crystal-clear day. The driver, an anarchist conspirator, scrambled down from the wagon and disappeared around the corner. A moment later, two hundred pounds of dynamite packed with broken window weights exploded.

The violence killed the dark-bay mare hitched to the cart and 37 people. Survivors of Bloody Thursday provided chilling descriptions of the mayhem, including a scorched man who rose and walked before falling over dead and the severed head of a woman stuck to the side of a building with her hat in place. The human carnage was cleaned up that night, but you can still see the shrapnel scars in the limestone of the old J.P. Morgan Building.

The scars to our collective psyche fade, only to be replaced by fresher wounds. But dare we conclude that New Yorkers of a hundred years ago didn’t have the same fear of bombs that we harbor today? Dare we presume that they didn’t startle at the sound of unexpected thunder or jump to conclusions when buildings collapsed?