PAY A VISIT to West Lothian in Scotland and you’ll notice that its landscape is dotted with mounds like mini volcanoes or a kid’s drawing of hills. But they’re not hills, or anything from nature really. They’re “bings” – piles of waste shale from mining. Today they mostly function as piles of aggregates for surfacing roads. Except, that is, for two of them, which are instead art. They were brought into being by the late British artist John Latham. Apart from turning bings into sculptures, he’s most well known for holding a party where guests chewed and spat out pages of a copy of the art critic Clement Greenberg’s Art and Culture – an influential, and pompous, book of criticism that cemented the terms of modern art. (The copy of the book they masticated also belonged to the St. Martin’s School of Art library, which wasn’t too pleased when the volume was returned to them in test tubes. Latham lost his teaching contract at the college.)

These two art-bings look no different than any of the other bings. No plaques or signs distinguish them. They were proposed as artworks during a residency Latham did with the Scottish Office, the country’s then governing administration. He declared that because the bings were both an important feature of the landscape and a by-product of the area’s mining heritage, two of them should be designated as monuments to the area’s history and future.

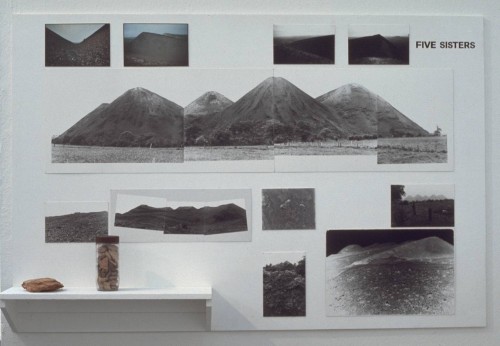

Each bing is actually a constellation of smaller bings. The first artwork was made up of four interconnected ones. From an aerial view, Latham saw in them the shapes of a woman’s head, torso and limbs, with a disembodied heart nearby. Out of this he created a monument, the Niddrie Woman, to commemorate the nearby town of the same name. The second bing was more straightforward and formed from a line of five connected bings. These became known as the Five Sisters, and in 2005, after a long battle with the owners (who still wanted to extract the oil from the shale), the Scottish Office gave it heritage status, which means it has to be left as is. Sadly, the Niddrie Woman is still prone to being mined – rendering what was already a pretty surreal image of a woman into something even more distorted.

John Latham, Five Sisters, 1976, Wood, photographs, glass jar and shale. The estate of John Latham , courtesy Lisson Gallery, London

That these bings were art and that Latham was there in Scotland was all down to the negotiations of the Artist Placement Group, or APG. A loose group of artists, it was led by Latham and his former partner Barbra Steveni, who wanted to see how artists could work outside the art world. APG wanted to change the status of artists and broaden their activities, so an artist could make a more direct contribution to society. The group brokered positions for artists in industry, government offices and corporations, and now a recent exhibit in London’s Raven Row Gallery has brought their work back into the public eye. The show collates the group’s monumental archive, which on top of laying out the letters and correspondence written to make the projects happen lays bare APG’s own way of mimicking business rituals and bureaucracy, an element that gives the group a surreal edge today.

Today, artists often work with corporations (think Louis Vuitton, Bloomberg, Becks beer), with their commissions and prizes. Artists also do residencies everywhere from on the London Underground to libraries, government departments and disused factories, all of which are meticulously arranged, with properly negotiated terms and careful auditing. Yet, when the APG started, the idea of the artist working outside the art world was new. Think back to the 1960s, that era of Mad Men. An artist embedded in a company? Doing anything other than layouts? But the 60s was also an era that eroded the very idea of artist. Art itself became conceptual and what constituted an object was up for grabs (just see the current Brooklyn Museum show on Lucy Lippard and the 60s and conceptual art).

Some of what is most interesting here is to see how Steveni and Latham went about eroding art too. They had no framework for their placements, so they simply negotiated with the management of whatever corporation they were interested in, until they came to a satisfactory arrangement. And many of the letters are included here at Raven Row. APG’s projects and placements came out of discussions the group had around the idea of the role of the artist and what artistic production means, both of which are common questions now in graduate art programs. But APG extended their questions even to what you might call an artist instead of, well, artist. They floated “environment engineer,” “concept engineer” even “incidental person.” As in, a person who causes an incident to happen. The idea was to create a term that didn’t automatically conjure up a person who might possibly be opposed to workers – in the sense of an artist being an “outsider.” The incidental person caused things to happen but was also part of the organization, only not in such a defined relationship as a worker.

One of the things that made APG radical was their arguing that the artist should be paid a salary by the host organization, regardless of their output. When artists got a placement, they were given an open brief – clear outcomes were not set out. The only thing the artist had to do was comply with the organization’s rules. In the end, though, there weren’t that many placements, and APG-instigated projects had varying degrees of success. Most pushed the boundaries of what constituted art.

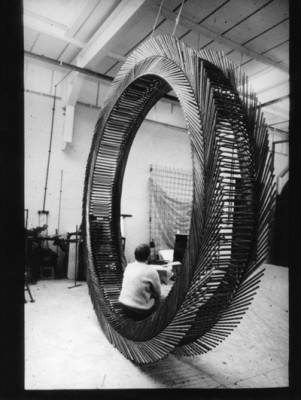

Stuart Brisley's Hille Fellowship installation, Poly Wheel – Robin Day stacking chairs. 212 chairs in a circle

The musician David Toop carried out a placement in the London Zoo, where he worked with partially-sighted children to explore animal sounds and sensory stimulation. He also created Earth/Zoo, which interspersed world music from the BBC sound archives with zoo sounds. The Raven Row installation reproduced it, transforming an otherwise empty room into a home of sounds—both human and animal. I might have been in a London gallery with its quotidian light fixtures but I was drawn into a parallel world of fragmented pulsating rhythms interspersed with sea lions, parrots and monkeys.

Others were hugely successful social projects, but not necessarily successful as art. Take a work with the Department of Health and Social Security in 1978-9, where a group of artists were invited to develop a series of aids to help elderly people reminisce. The artists conducted interviews with residents in nursing homes around London, using photos and sounds to trigger memories. These became slide sequences for different decades throughout the 20th century. They were so successful that the UK charity, Help the Aged, acquired their rights and marketed them as a product called “Recall.” Product, yes. Art? Well, no.

My favourite APG project almost has a comic feel to it and was as much about the workers and the artist finding a way to co-exist, as about art itself. The artist George Levantis sailed with three different cargo ships. The first two trips were hugely successful: he took photographs and recorded conversations with the crew, and in return drew portraits and gave art classes and everyone was happy. On the third voyage he was asked to make art objects, so he created installations with found materials around the boat that dealt with different aspects of his sea-bound experience. The crew wasn’t very impressed by these ad hoc artworks and many of them were thrown overboard.

As you might have guessed, it’s easier to describe the works that APG artists made than to describe seeing them in the gallery. The viewing experience is rather like being in a library. Projects are shown alongside all the related documentary and administrative material so you get a mix of the final works and the correspondence that led to them. After exploring the details of John Latham’s feasibility study with the Scottish Office, you come across a breathless dictaphone recording of Barbra Steveni’s to-do lists. Mundane perhaps, but this idea that art isn’t an object extends to the documentation, that perhaps it too is now art and an object. The exhibit includes Steveni’s ever-increasing volumes of letters she wrote to various managers, in perfect management-speak. They point out just how surreal the language of management power is, and it’s this mirroring of management speak that’s most interesting about APG. They’re playing with the language of power, perhaps with subversive aims or perhaps to empower themselves.

APG’s questions, like “What else can come of making art?” and “Is making art enough?” are still common now. Perhaps their lasting legacy is not their individual projects, but the fact that they were at the forefront of interrogating what it means to be an artist, and what art can do. When Latham proposed that the bings become monuments to the area’s history, he also challenged the idea that monuments celebrate the great men of history. Instead he wanted to celebrate the work of a community. Recently this sort of rethinking monuments has become popular, as in London’s Trafalgar Square, where the Fourth Plinth has been home to contemporary work, including Anthony Gormley’s “One and Other.” It saw different people occupy the plinth every hour, 24 hours a day for 100 days in 2009.

Meanwhile Barbara Steveni continues to work with the APG’s archive under the guise of what she calls “I am an archive,” where she deploys their work in different contexts to see how it can be relevant today. For her this is way of both keeping the organization alive, and seeing how the experiences of artists 40 years ago can be applied to today’s social situations and what can be learnt from the APG. Her work with all those letters and documents has almost become an artwork in itself.