IT PAINS ME to say this: I’m increasingly ashamed identifying as a comic book nerd. It isn’t for the usual reasons. I don’t feel the shame of having to hide underneath my covers to read comics by flashlight. I don’t feel shame over the posters in my office or the references I make. I’m not ashamed because I can argue the superiority of Wally West and Kyle Rayner over Barry Allen and Hal Jordan. But I do feel shame, not because of what I like and how I like it, but because what I like expresses itself in an increasingly ugly way.

Growing up, I was incredibly obese. Although I had always been plump, this tendency accelerated after my parents’ divorce and my father’s subsequent death, when I was nine, from liver failure. By the standards of young boys, I was the outcast. I couldn’t play sports so I never joined a junior team. My body held me back throughout elementary and middle school so I grew accustomed to making excuses for my weight.

I joked about it, hid it, wore a shirt in the pool. Gym class, compulsory in Illinois, was a nightmare. I had my nose rubbed in proverbial shit by gym teachers because I couldn’t perform a layup when it was time to “learn” about basketball. In seventh grade, I missed enough school to almost get my mom in trouble with the authorities because I was so cowed by a table of older bullies, positioned right at the end of the lunch line, which routinely pulled me over and mocked me from round head to sausage toes.

This is where a lot of antisocial behavior can come from. However, my interests sustained me and got me through this time. I had my TV shows and my video games but, above all, I had my comic books. While I’ve always been, and am still, a fan, comics never made a bigger impression on me than they did then.

Iron Man and Batman were my wish fulfillments. Maybe it was the former’s mustache and drinking problem that reminded me of my father, triggering some instinctive paternal devotion, but both characters seemed to have a handle on things in a way I didn’t. They were in shape, had it all, and, of course, could get any girl they wanted. This was all wish fulfillment, as many comics are. They can be power fantasies, or moral instructions, or parables soaked in derring-do and adventure, but as I grew older and more sophisticated in my understanding of the medium, I learned that, at their core, many comics were about embracing, even celebrating, the outsider and working towards a better world.

Consider the X-Men: a group of outcast teenagers rejected by society due to their identities, abilities, and proclivities. While the earliest X-Men stories featured a cast entirely comprised of WASPs, later stories, starting in the mid-70s with Chris Claremont, Dave Cockrum, and John Byrne, featured an international cast that has spawned a media empire. How about Spider-Man? Geeky and bullied teenager Peter Parker becomes a superhero, something that seems more of a curse than a blessing as he juggles failures both personal and professional. And there’s Daredevil, the blind Matt Murdock who overcomes his disability and defends the accused as a lawyer by day and punishes criminals by night.

All of these characters were outsiders, appealed to outsiders. Sure, they may have been drawn to physical perfection, but, at their core, they were alone, set apart, and either were mocked about or kept secret their true identities and abilities.

The be-all-end-all of outsider superheroes is, of course, Superman. Born with powers far beyond those of mortal men, the ultimate outsider, Superman, in the Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster originals, was a social crusader. He fought wife beaters, corrupt landlords, exploitative industrialists and capitalists. Superman deposed Hitler and Stalin, dropping them off at the League of Nation’s headquarters to stand trial for war crimes. The guy even fought the Ku Klux Klan on the Superman radio show. And, with his square jaw, broad shoulders, and spit curl, he looked good doing it all.

This spirit of progress is rich within comics. Wonder Woman is a powerful, liberated female, sent as an emissary to “Man’s World,” to promote harmony, dialogue, and understanding between the sexes. Batwoman is a proud ex-solider, ostracized from the military due to her homosexuality, that has turned to crime fighting to make the difference denied to her. Professor Charles Xavier is confined to a wheelchair but is seen as one of the foremost enlightened minds of our time. Luke Cage, a wrongly convicted criminal, defends his native Harlem against criminals and oppressors, from outside or from within. Green Arrow is a selfish playboy turned outspoken liberal who is less concerned with petty crime than social justice. Apollo and Midnighter are the physical epitomes of masculinity and a committed homosexual couple. The Black Panther is T’Challa, king of Wakanda, an African nation resolutely, and successfully, opposed to Western imperialism. Lois Lane is the career woman who can, and does, have it all. The Legion of Superheroes is a group of teenagers and aliens from the future, brought together from different worlds across the galaxy to keep the peace and foster interstellar harmony.

These are all characters with a certain degree of difference. They are all marked by what they stand for or who they are that differentiates them from the accepted mainstream. In essence, they are, as good superheroes should be, unconventional. They are beyond the pale and always figure out new ways to solve problems. Whether its overcoming the law of physics or overcoming no win solutions with viable third ways, they were outside the box. And I love them all. I had, and still have, room in my heart for everyone one of them, even beyond those listed here.

Nevertheless, my love of comics and the characters populating them seems to be fading. Maybe the love is morphing into a different kind of affection, where the warts really start to show, but I’m starting to feel, frankly, embarrassed. Superheroes were, for me, outsiders. My bond with them hardened when I felt to be an outsider. For starters, they went outside the law. Factor in their amazing abilities, unconventional identities, and you have an instant attraction for someone, like I was, who grew up an outsider.

But superheroes, perhaps comics as well, are no longer about outsiders, for outsiders. They’ve been mainstreamed, gobbled up by the public, and rake billions in profits from movies, TV shows, and video games for their corporate masters. For many people, superheroes are creations leaping off the silver screen, not the printed page. Indeed, I’ve had people look at me quizzically, baffled when I say that superhero comic books exist. With superheroes gaining a wider audience, their contours have altered.

Have you ever been to a comic book convention, hosted in seemingly progressive places such as San Diego, New York, Seattle, or Chicago? It’s mostly a display of the same exploitative, cheesecake art and background misogyny that increasingly define the appearance of women in superhero comics. Yes, there’s an element of costume, fantasy, and dress-up, but it often leaves me with the distinctly unclean feeling that I’ve stepped off the convention floor and stumbled into a meat market where exposed flesh is the medium of exchange.

None of this used to bother me. As a large kid, mocked by other kids with more traditional bodies, I latched on to superheroes. I developed a kinship with these characters because of their physical perfection. Being someone scorned because his body was far from the heights of perfection, how could I not gravitate towards those who possessed physical perfection in spades? Essentially, I wanted to be the stereotype, progressive inclusiveness be damned.

From comic artist/writer and uber-bro Todd McFarlane: “As much as we stereotype the women, we do it with the guys. The guys are all good looking, not too many ugly superheroes. They’ve all got their hair gelled back. They have got perfect pecs on them. They have no hair on their chest. I mean, they are Ryan Gosling on steroids. Right? They are all beautiful. So we actually stereotype and do it to both sexes. We just happen to show a little more skin when we get to the ladies.”

Men are stereotyped to the preferences of males. Women, in superhero comics, are shackled to the sexual proclivities of heterosexual men. The only equivalency here is that both representations are geared towards people with penises. And as someone with a penis, I was once dazzled by these representations. It likely wasn’t something I was conscious of. For the most part, the attraction dwelt in the vestigial reptile brain we all possess.

That’s what’s insidious. I was hooked by comics because they portrayed the outsider. Little did I know that other forces, unthinking forces, might be at play. Growing aware enough, it’s not unlike Roddy Piper in They Live: once you put on the special sunglasses and see what’s around, you can’t go back to the way things were.

Such unthinkingness is widespread in superhero comics. For example, take Mark Millar, widely known for the limited series Kick-Ass and the recently adapted Kick-Ass 2. In the story, the titular hero’s love interest is beaten and gang-raped. This is all rendered in the exactness and bodily precision that’s a hallmark of superhero artists. Thankfully, this scene was omitted from the feature film. Nevertheless, it is Millar’s cluelessness of his critics’ charges that infuriates me. In an interview with The New Republic’s Abraham Riesman, Millar says: “The ultimate [act] that would be the taboo, to show how bad some villain is, was to have somebody being raped, you know? I don’t really think it matters. It’s the same as, like, a decapitation. It’s just a horrible act to show that somebody’s a bad guy.”

Let Laura Hudson, former editor of ComicsAlliance, a popular comics blog, respond: “There’s one and only one reason that [rape in comics] happens, and it’s to piss off the male character. It’s using a trauma you don’t understand in a way whose implications you can’t understand, and then talking about it as though you’re doing the same thing as having someone’s head explode. You’re not. Those two things are not equivalent, and if you don’t understand, you shouldn’t be writing rape scenes.”.

Comic books aren’t the best way to bring home the bacon. Superheroes, although the most popular and profitable genre, still have a pitifully small readership. It’s a tangential, niche, outsider medium. Superhero comic readership, those that go every Wednesday to buy comics, has been estimated to be no more than 200,000 in the United States. Add a hundred thousand or so from friends or family member that share these comics, and you still have a miniscule base to work from.

Here is Todd McFarlane again, when asked at a panel what he would do to draw in more women superhero comic readers: “It might not be the right platform. I’ve got two daughters, and if I wanted to do something that I thought was emboldened to a female, I probably wouldn’t choose superhero comic books to get that message across. I would do it in either a TV show, a movie, a novel, or a book. It wouldn’t be superheroes because I know that’s heavily testosterone-driven, and it’s a certain kind of group of people. That’s not where I would go get this kind of message, so it might not be the right platform for some of this.”

This is the exact mentality that I’ve grown ashamed of. It’s the mentality that nothing can be changed. Things, as they are, are how they will always be. This is the mentality of those bullies that harassed me because, back then, they were, naturally, the ones in power over me. How could it be any other way? I had the wrong body. They had the right ones. This is the natural, normal, unthinking course of events. The fat outsider gets his food tray smacked to the ground, finds himself pushed into lockers, gets cornered in the bathroom.

So I retreated. Superhero comics got me through that period. They made me work to lose weight, to go from 250 pounds in eighth grade to 170 pounds my freshmen year, a task so impossible I hardly believe it sometimes. Superheroes gave me the power to envision something better, an alternative, an outside option.

But I conformed my body to become what’s called normal or ideal. I worked hard, lifted weights, ran, exercised, all done to bring my figure closer to those I idolized. I healed myself not by fighting for acceptance because I looked different but by discarding those differences. Instead of standing up for who I was, with all my strange and unusual properties, I turned tail and decided that I should look like those who bullied me.

It might be said that I should move on from superheroes, that I should realize that they have always been simplistic and juvenile. Some might say that, in doing so, those last bits held over from the heavy, isolated kid inside of me might die. So much of who I was then has already gone that way. I can, finally, progress, move on with my life. Become an ‘adult.’ Embrace the fact that my appearance is finally accepted because I’ve changed.

I reject that. While not a superhero in the conventional sense, another hero of mine, Mr. Rogers, always said that he loved me just the way I was. It was a message for a child, spoken from someone who remained a child at heart.

Superheroes are for children but only in the most wondrous ways. They’re for children and the child at heart because they present a world that doesn’t just operate on the ‘because’ or the tried and tested. They operate by finding another way, a better way. Don’t believe what you see in marketing. Superheroes are not about being sleek and sexy. They are not just about the violence, the spectacle, the special effect, the body. Superheroes are about taking that most innocent, childish of questions—Why?—and adding a coda: Why not?

This is a treasure to read. What can I say except Bravo, and Thank You. From one comic book fan to another, thank you for writing this article. It touched on so many things I love about comics, loathe about comic book makers, and want to change for the future comics my son or daughter will read.

Great work. I hate the comic book industry and its desperation for mainstream fame: their marketing ploys, Today Show spots, and constant apocolyptic brand 0f storytelling alienates me constantly. This article does a great job of showing that, while conformity does seem diametrically opposed to the draws and fan base of comic books, the industry is so quick to conform. It feels like the medium, especially superheroes, could be a great place to lead the way in representation. At least we have creators outside the DC/Marvel world that continue to work with female, minority, and LGBTQ characters brilliantly.

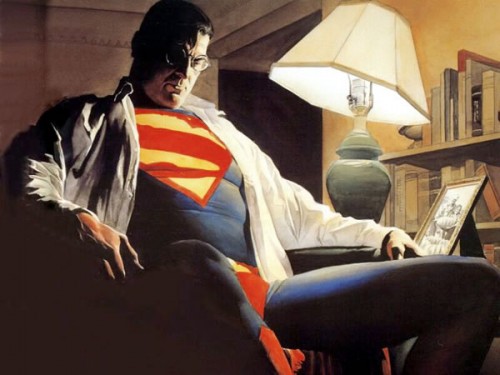

Also, it is impossible to talk about comic art without talking about the brilliant Alex Ross. Great photo by him at the end there. His Batman is the defining Batman, in my opinion.

Did you decide to look more like those who bullied you, or the superheroes you idolized? It seems to me that simply because you no longer look as you used to doesn’t mean you’ve lost what made you you, unless being overweight was in itself a part of your identity, almost a point of pride in some convoluted way. Mr. Rogers said he loved you just the way you were, and that applies at every point in time: he’d love you for who you’ve become as well. I don’t think that being loved as you are has to equate to resistance to change; I think it can and should be a foundation to enable you to launch into becoming whoever you choose to be. And if you choose to be healthier, I don’t think you’re making a concession to society, only stepping into your true power, building character through the act of taking control of your life, and perhaps using what you find in yourself through the experience to help others as your heroes do.