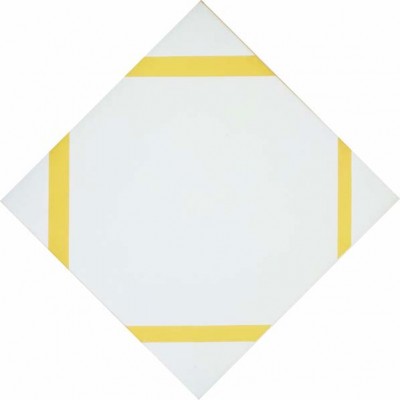

“HE HAD DISTILLED the art of painting into its purest essence and rendered it complete. And every painting that had pointed at God or the muse or money or fame now pointed at Composition with Yellow Lines.”

When I was younger, I published a novel whose first chapter describes the protagonist attending a Mondrian retrospective at the age of seventeen. (Above you see what he thought of Composition with Yellow Lines.) I based the chapter very loosely on my own memory of attending “Piet Mondrian: 1872-1944” at the Museum of Modern Art in 1995, but I referred to an unrelated little Taschen paperback for the images. Several years after the book came out, an editor who’d read the book invited me to start writing gallery reviews for the New York Observer.

In Islamic law, the Koran is supplemented by a body of anecdotes about the life of the Prophet. The Prophet’s truth comes directly from the source, by definition, but what happens afterwards is always open to question, so each anecdote is followed by a punctilious genealogy of transmission. It wouldn’t be enough to say, “The Prophet, peace be upon him, was heard to remark, ‘Tough guys don’t dance.’” To make the statement binding as a matter of law, you’d have to add, “which I heard from Frank, an honest man, who heard it from Joe, who heard it from Boomer, who heard it from Nathaniel, the Prophet’s friend, who was definitely there.”

While I was working on this novel with the Mondrian chapter, I had an argument with a friend who later became an art historian. I proposed to her that by reducing painting to its most basic elements—black lines, white space, and primary colors—Mondrian had “completed” it. As I remember the conversation—though my friend remembers it differently—she wanted to know whether I believed this theory to be true, and became very frustrated by my insistence that it didn’t matter.

For my first review at the Observer, I was assigned to write about Mika Rottenberg’s video “Squeeze,” a twenty-minute looping fantasia about industrialism, imperialism, and sexual commodification that was screening inside a specially built plywood box in the middle of Mary Boone’s gallery on 24th street. I’ve plagiarized the phrase “looping fantasia” from myself because it still seems the neatest way to say what I think, and I think it would be dishonest to misrepresent my honest opinion just to avoid repeating myself.

Mika Rottenberg "Squeeze" (film still). Single-channel video installation 2010, Courtesy of Mary Boone Gallery

It’s not true to say that my friend the art historian remembers our conversation differently. I did ask her about it, but the truth is that she didn’t remember it at all. It was more than ten years ago, and I only remember it myself because I found the difference in our attitudes so striking. I also remember that in a group show neither of us liked, during the same week-long trip to London, she took the time to look at the work, anyway, and think about why she didn’t like it, while I went to wait in the lobby.

I didn’t realize that I could ask the gallery for information, and I didn’t want to get anything wrong. So I sat through several showings of “Squeeze” taking copious notes about sequence and physical detail. I knew that even my phrasing and choices would reveal my biases as a writer and viewer, but I thought that confining myself to concrete description would at least be more honest. There’s only so much I can do about the inherent biases of my vision, but I do know what I think I’m seeing. If I ventured to generalize, however, I wouldn’t even know whether I meant what I said.

I remember being very surprised to discover, the first time I took a life drawing class, that my mind was infested with visual as well as verbal cliches. I thought I knew what an eye looked like, for example, and so I couldn’t just look at a model’s real eye and put down what I saw. At the same time I had to clear away what I thought I had already seen. I often struggle to describe things in a phrase or metaphor because I’m ignorant of an apropos technical term. But I like to imagine that this struggle lends my work rigor.

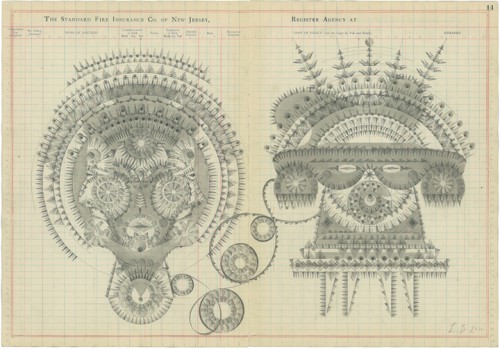

The week before Christmas, I went to see two shows on the Lower East Side that I thought I’d like to write about. Louise Despont has a show of dreamily elaborate pencil drawings on old ledger pages at Nicelle Beauchene Gallery, and I thought I’d enjoy reliving their warm sensual appeal in my own language. At Invisible Exports on Orchard Street, meanwhile, was a show of classic gay pinup photography by Bob Mizer. Ending a review with a show whose context demands more words than its content is like adding a sorbet course.

Louise Despont, "No. 14," 2010, Graphite on antique ledger book pages. Courtesy of Nicelle Beauchene

I was filling out a grant proposal when I first started thinking about enlarging my close observation to encompass the larger context of an encounter with a given piece of art. I proposed writing about the gallery space, the prices, the weather outside, what I’d passed on the street on the way in. I said it would be more honest and actually more objective to include the circumstances of my viewing, to be more frank about my own feelings, because my own feelings are all I have to work with. I was surprised to find, after I’d written this, that I actually believed it.

If my friend had phrased her question differently, I might have given her a different answer. Or at least I would now. If she said not, “Do you think that’s true,” but, “Is that what you honestly think,” I might try to give an idle thought more substance by making it more specific. I might try to reveal its particular truth by locating it within a recognizable context.

In his 1923 book I and Thou, Martin Buber infused the prophetic tradition he had inherited, in which truth is a divine given to be recognized or degraded by human beings, with a meditative nontheism. He proposed the moment of encounter between self and other as a self-evident, indubitable, absolute truth. That much is hard to argue with. But he also said that this was not a truth that could be described or communicated.

Last winter I wrote about another MoMA retrospective, this one of filmmaker George Kuchar at PS1. In addition to more formally staged movies, Kuchar edited together hundreds of shorts from footage he shot in the course of his ordinary life. This rough naturalism makes his work seem inexhaustible. I know it isn’t true, but I can’t help imagining that Kuchar had some kind of artistic philosopher’s stone that could transmute anything he saw, felt, or laid his hands on into art. Since that show I’ve been wondering what such a device might look like for a writer.

After Christmas I went back to Orchard Street, intending to stand around the galleries for hours taking sporadic notes. But I had forgotten that even gallerists take vacations. I considered writing the review from images available online, which I don’t like to do, but which could, for this essay, have served as a useful metaphor for the critic’s insuperable remove from his subject, or more generally for the thinking subject’s unbreakable remove from the world.

While I was deciding what to do, I went to have lunch at a nearby restaurant, Mission Chinese Food. It’s decorated like a Japanese izakaya, with hanging paper lanterns and woodblock print demons. On one wall near the bar is a garish painting of Kim Il-Sung and nine other generals on horseback. I ate fried noodles and wondered why we can ironically appropriate Communist iconography but not, say, Fascists or Nazis. I’ve heard people say it’s because the Russians were on our side in the Second World War, but I think it has something to do with America’s pathological fear of property redistribution, a forbidden fascination analogous to homophobia.

I might say that if you conceive of Western figurative painting since the Renaissance as a progress toward more and more accurate representation of what the eye actually sees; and look at Cézanne’s apples; and take the Impressionists at their word about what they thought they were doing; and follow the development of Mondrian’s abstraction from his somewhat schematic early figure drawings and paintings, recognizing in it a systematic distillation of elements; then it might be fair to say that his best-known later works do represent a kind of terminus, for whatever that’s worth.

When Jen Kabat invited me to write about writing about art for The Weeklings, I proposed writing an essay in parallel to a review: while examining, thinking about, and attempting to rigorously describe some particular gallery show in New York, I would also examine, think about, and attempt to rigorously describe my own experience of the attempt. This would give my observations more substance by making them more specific, while also giving me twice as much writing in the same amount of time.

Last summer, I wrote a fall art preview piece while I was out of town, for which I did have to use images online. Once back in New York, I discovered that my description of the paintings in Louise Fishman’s September, 2012, show at Cheim & Read as being composed of “broad strokes of oceanic or Marian-blue color . . . fitted together like tiles” was completely wrong. I got the color right but completely missed the paintings’ depth.

The body of anecdotes about the life of the Prophet is called the Hadith, and I’ve never read any of it. I probably read about it as an undergraduate, which is also when I first read the Koran. I must have read Orientalism, too. I thought I wanted to mention the Hadith in order to point out how difficult it is to tell the difference between arrogating authority to what you say and disclaiming responsibility for it: “what I say is true, because I am not the one saying it.” But I realize now my point is only that the transmission is part of the story.

Far from struggling to make contact or communicate, you could say that we’re none of us ever doing anything but communicate. Anything I say about Mondrian’s paintings, for example, however fanciful or inept, or however sincerely I might believe that I’m only writing “fiction,” will be something I really have said about Mondrian’s paintings. Nearly seventy years after his death, it will also be something I really have said to him.

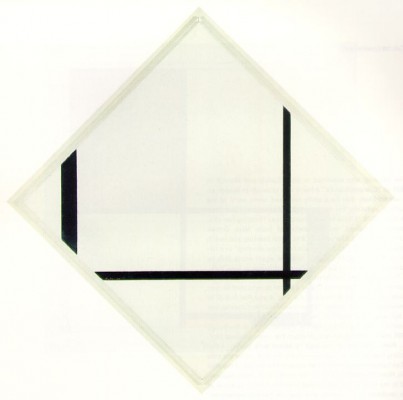

On the other hand, if my friend had then asked me whether I thought that was true, or important, I still wouldn’t know. In his last two paintings, “Broadway Boogie-Woogie,” 1944, at MoMA and the unfinished “Victory Boogie-Woogie” at the Gemeentemuseum in the Hague, Mondrian’s lines have broken up into dots. The German-born painter Jan Müller, who worked in New York in the 1950s, made paintings composed of broad, brusque, overlapping lines of color, like mosaics come to life. I have a pet theory that if Mondrian had lived longer, he might have worked his way back around to figuration in a similar way. I mentioned this idea in a review of a Jan Müller show at Lori Bookstein last May.