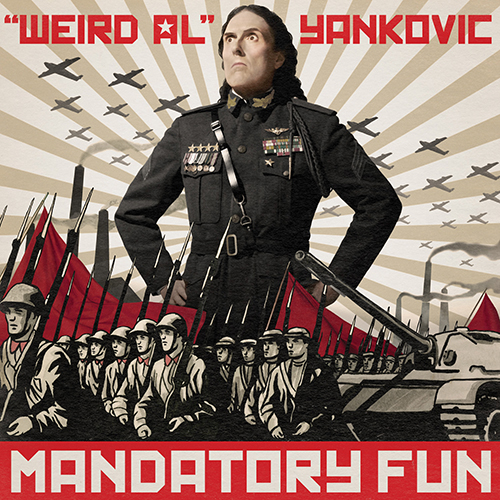

WHEN “WEIRD AL” YANKOVIC’S ALBUM Mandatory Fun debuted at #1 on the Billboard chart last year, the mood among his legion of fans was triumphant: he deserves this, he has deserved this.

At last, more people than ever recognize his importance in the sphere of popular music. Is it because this generation – who’ve loved his records since childhood – has finally grown old enough to hold positions of power in the music business? Or is it because a disciplined artist like him, dedicated to a high standard of quality, must merit recognition after nearly 40 years of work, no matter the genre? Perhaps his award portends a general leaning toward the funny and fun in mainstream music, to delight frivolity fans (like me) everywhere. (I doubt it, but one can hope.) Whatever the reason, Yankovic’s victory is a thrill. His tradition is a rich one, his craft way more complex than most realize – and comedic songwriters can rejoice, albeit in many cases from beyond the grave, at the honor.

Whimsy and irreverence are powerful, underrated forces in the musical world, and there are indeed a lot of funny musicians. Consider the wild and nutty vocal improvs of Slim Gaillard; the bitter wit of Warren Zevon; De La Soul’s offhand, back-of-the-classroom-style quips; The Andrews Sisters and the Supremes imitating each other before Sammy Davis, Jr.; Black Flag yelling out the names of TV shows; the Butthole Surfers doing pretty much anything.

Comedians who play music have always been a staple, like Steve Martin and Martin Mull, or, if you prefer, Adam Sandler, Jimmy Fallon and Sarah Silverman. And comedians have pretended to be musicians for comedy’s sake (“Rappin’ Rodney” Dangerfield, for one). Very few succeed as both comedians and musicians simultaneously, but those who do have turned out some sublime music: insane Spike Jones and his City Slickers, the brilliant Bonzo Dog Band, Neil Innes’ faux-fab Rutles, and – lest we forget – the Marx Brothers.

Too often as I was growing up, though, comedy songs were lame, halfhearted copies of hits, mailed in to a local radio station but heard just as far as the air signal and only for a couple of months. I remember one from FLY 92.3 in Albany: “Rice, Rice Baby,” a song about a Chinese restaurant: If I get dessert, you know I deserve it / Check out the food while the waiter serves it. Another, up in the Adirondacks, was a parody of Paula Abdul’s “Rush, Rush” entitled “Bush, Bush” all about how the singer wanted George H.W. Bush to win the Presidential election in 1992. Now and then came holiday songs, a shining example being “Grandma Got Run Over By a Reindeer.” Diligent Dr. Demento would find the best of these regional novelties, play them on his syndicated show, and compile them every year or so into an album. I still have and cherish my Demento comps, but it must be said that most of the material is in questionable taste and/or hasn’t aged well. They’re worth it for the classics and the odd gem, something from a person with a greater stash of funny stuff to show. The biggest goldmine among Demento’s discoveries, back in the late 70s, was 16-year-old Al Yankovic.

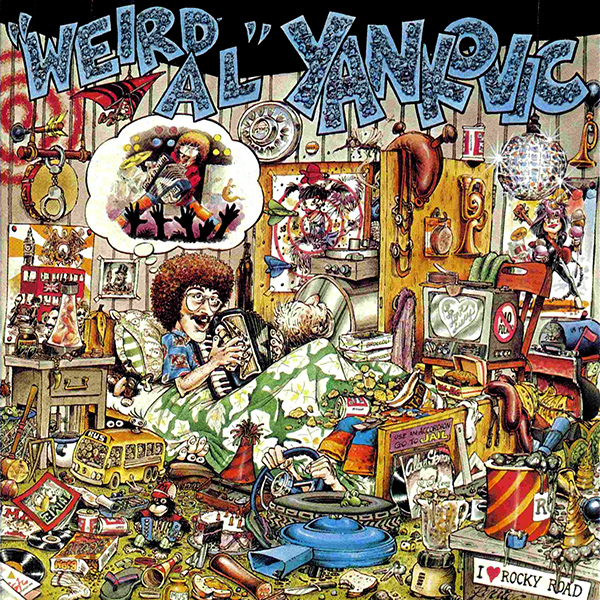

When “Weird Al” released his first album in 1983, with a cover illustrated by cartoonist Rogerio, astute fans noticed a reference in the art to one of his idols, Allan Sherman. The drawing was of Yankovic’s cluttered bedroom; visible amid the wreckage of posters and toys was a Sherman LP. This was a bold declaration, a line drawn in the sand, considering the prevailing climate of new-wave ultracool into which Yankovic’s songs were being introduced.

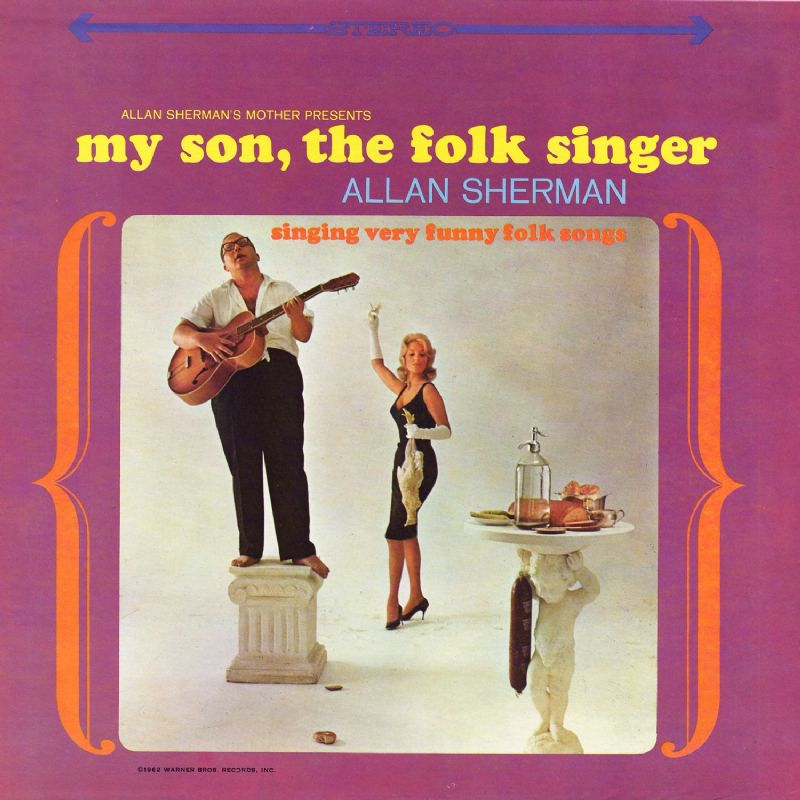

Sherman had been beloved of a demographic of 1960s squares, anti-hippie and anti-beatnik moms and dads who drank up the gags in “Hello Muddah, Hello Fadduh” like so much celery soda. The children of these jocund Madison Avenue types grew to cringe at this schlock, albums like My Son the Folk Singer and Allan in Wonderland that spoke satirically to the plight, such as it was, of the middle-class everyman. Never mind that Sherman was another master, criminally uncool yet happily fluent in his idiom, his niche. His specialty was writing parody lyrics to traditional songs, “Hello Muddah” for instance being sung to the tune of La Gioconda’s Dance of the Hours, and “Harvey and Sheila,” a love story starting in an office building, to “Hava Nagila.” Just try to listen to either – or his “Twelve Gifts of Christmas” that recounts a dozen tacky presents in festive fashion – without smiling.

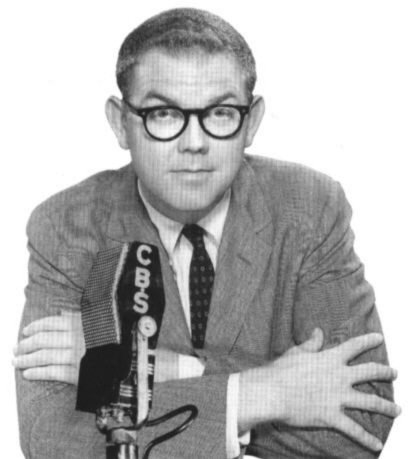

Meanwhile, slick voice actor and advertising writer Stan Freberg trafficked in a humor that was similarly jovial but more Hollywood, and a bit more cutting. He used his immense talent for mimicry to send up popular songs like “The Great Pretender,” “Sh-boom,” and “Heartbreak Hotel” in a way that made them sound less genius than ridiculous, yet still like great, entertaining records. His parody of Harry Belafonte’s “Banana Boat Song” has him arguing throughout with a beatnik bongo player who whines that his voice is too “piercing,” but both the bongos and Freberg’s Calypso singing are actually excellent, almost authentic.

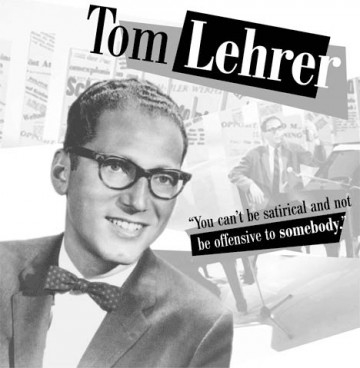

For the Ivy League set, there was Professor Tom Lehrer, acerbic and erudite, whose mostly original tunes—plinked out cutely on his piano and sung in a nasal tenor—could be downright evil in their cruelty. (One of his most famous compositions, “Poisoning Pigeons in the Park,” deftly finds rhymes for both “cyanide” and “strychinine.”) I can listen to this stuff for hours; to my non-Baby Boomer ears, it sounds both fresh and refreshing. Other pop songs, overwhelmingly, are about love: being in it, falling out of it, hearts breaking, love unrequited. What relief, after half a life of that, to hear pert little ditties about nuclear war or being a tourist in Mexico.

The common thread in all these 1960s singer-comedians, besides their charisma, was a telegraphed contempt for the counterculture. There is an anti-hipness in these songs, occasionally condemning youth culture outright (as in Lehrer’s “The Folk Song Army”), but more often just celebrating the choice to reject it. Though it shouldn’t be said that they had no use for the peacenik image of the 60s – this provided such fertile ground for mockery, after all – their songs frequently feel like a wink in the direction of those who didn’t buy into it: conservatives; parents; and, importantly, younger children. People under 12 may be confused about what’s hip, but they sure as hell understand what’s funny.

I was once watching VH1 Classic with a friend when we realized we’d each heard “Weird Al” Yankovic’s “Fat” easily a hundred times more than the song it parodied, Michael Jackson’s “Bad.” My friend and I were lucky to be kids at a time when Michael Jackson was hot, and was everywhere: we’d sing and wriggle to “Bad” when it came on the radio in our parents’ cars or at the roller rink. But we didn’t really understand what it was about, just that it was cool and we liked it. Yankovic gave it new lyrics that we did understand – an 800-pound wonder proud of his fatness – and even a big-budget video that borrowed sacred tropes like the jeweled glove and the moonwalk. This made Yankovic our hero. Better yet, “Fat” was also a quasi-sequel to “Eat It,” the spoof of “Beat It” that had come out a few years earlier. A decade later, parodies like “Amish Paradise” and “Constipated” made a whole new crop of ten-year-olds champion him, and now, a good decade-plus after that, he is still making new fans.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t2mU6USTBRE

Satirists like Yankovic and his forbears have become beloved of kids, but early audiences for song parody were decidedly adult. Sherman got his start performing at Harpo Marx’s private parties, for instance. However, many of the songs that fascinate me most have been recorded, ostensibly, for children. There’s the whole MAD magazine aesthetic, seen also in Dr. Demento’s twisted bag, relying in part on a Nickelodeon-style poetics of grossness, nose-picking and green slime. But kids have also been lucky enough to hear innocence, like Bob Dorough’s sweet songs for Schoolhouse Rock; Ross Bagdasarian’s cheeky Chipmunks; and best of all, the brightly energetic, jingly-jangly music of Joe Raposo.

These songs, again, aren’t about romance; they’re about aardvarks and numbers. But how remarkable the Sesame Street songs are, and how remarkably funny. You need humor to create a song like “Being a Pig,” or like Jeff Moss’s “Rubber Duckie.” (Note: Though music director Raposo was responsible for the majority of the show’s memorable tunes, Moss wrote several of the best, such as “People in Your Neighborhood” and the exquisite “Captain Vegetable.” Another great was the animator Bud Luckey, who penned a series of number songs including “The Alligator King” and “Ten Tiny Turtles on the Telephone.” In the former, one of the alligator sons gives the king “seven statues of girls with clocks where their stomachs should be,” an Allan Sherman reference from “The Twelve Gifts of Christmas”!) Lively visuals accompanied them, predating MTV by several years. Raposo, a former stage composer who cited Spike Jones as his biggest influence, eventually recruited Tom Lehrer to write songs for The Electric Company, Sesame Street’s funkier offshoot for older kids. Lehrer’s “N-apostrophe-T” remains a standout.

The thing too few comedy songwriters seem to grasp is that you don’t just need to tell jokes in song. You need to make good music. Christine Lavin’s “Sensitive New-Age Guys,” for example, which had a good run in the early 90s as a novelty song, is really a pearl by an expert folk musician: clever lyrics like “Who like to cry at weddings? Who think Rambo is upsetting?/Who tape thirtysomething on their VCRs, who have Child-on-Board stickers on their cars?” sound delightful over Lavin’s nimble acoustic guitar-picking, in her smooth, clean singing voice. Neil Innes and the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band, who never labeled themselves as anything but a comedy act, achieve uncanny verisimilitude with Donovanesque flower-child rock in “The Urban Spaceman,” which was produced by Paul McCartney—and Innes and Eric Idle later created a large catalog of Beatle pastiche as The Rutles. Each recording, more than just being a convincing copy of the original, stands on its own as a cool song.

To return to Weird Al Yankovic, it speaks to his high musical standards that the pop artists he makes fun of tend to like him. At the beginning, Doug Feiger of the Knack gave his blessing to the parody of “My Sharona,” unfazed at the title “My Bologna.” In an interview, DEVO’s Mark Mothersbaugh described first hearing “Dare to be Stupid,” an affectionate riff on DEVO’s sound, and being both amazed and depressed by how well Yankovic had nailed it. “I was in shock,” Mothersbaugh said. “It was the most beautiful thing I had ever heard… I hate him for it, basically.”

Something else satisfying about Yankovic is that he himself cannot be mocked: not anymore, not successfully. As this rare misstep from the Onion showed in 1999, jeering at such a goofy, good-natured and undeniably smart entertainer just makes you look mean, joyless. By contrast, 30 Rock got it right in an episode with Yankovic as guest star – he hits with his parody of Jenna’s earnest song, and again by creating an earnest version of a song about farts which she wrote expressly to thwart him. Weird Al seems to have moved past any disdain past parodists may have shown for musical trends, and instead is just declaring that life can be one big cartoon, if that’s what you want it to be.

Many of these funny people are no longer with us. With the passing of Stan Freberg just a week ago at the time of this writing, there are fewer of his kind out there than ever. The traditions that inspired them – music-hall, vaudeville, Borscht Belt, Broadway – are hardly the robust cultural forces that once prevailed, so their own music will have to suffice as fuel for the next wave. I hope there is one. As mentioned above, many musical artists are funny, and many comedians are musical. I think that may be why relatively few people come into their own specifically as comedy musicians; they choose to be one or the other. But, also, it may be that in order to attain the status of legend in the genre (rather than just a flash in the Dr. Demento pan) you have to be so, so good. The ability to make people laugh is even rarer than the ability to make beautiful music – the combination of both, executed well, is cause for celebration.