Each of the Weeklings’ editors (along with a few friends) has chosen one David Bowie song that made a difference in their life, without restrictions or any particular reason: musical, nostalgic, shock value, bass line, bad video, dance move, vocal tic, lyrics, or just pure genius.

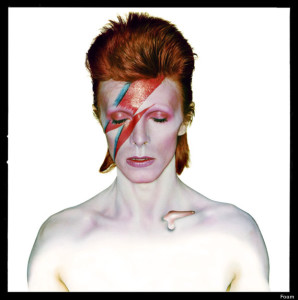

ROBERT BURKE WARREN – “Ziggy Stardust” The Rise & Fall of Ziggy Stardust & the Spiders from Mars (1972)

IN 1980, MY DEAR CHILDHOOD COMPANION, Todd, introduced me to The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars. He gave me the album as a fifteenth birthday present. It had been out for eight years, but not on my radar, as I was a devotee of Top 40, and Bowie would not hit that demographic hard until ’83. Todd and I had seen Bowie the year before in his super freaky historic SNL appearance, and frankly, I hadn’t been ready. Todd had been, though.

This was the first time I received an LP as a gift. Todd and I had been friends since we were very small, and we were fitfully becoming sexual creatures – me, a hetero; him, a bi-curious adventurer. These changes had put a strain on our friendship. Todd was nervous about my response to the gift; I could feel his anxiety in the yellow of his front porch light. He needn’t have worried. I loved it. I got it. Ziggy was a bridge.

The album spoke of gender bending, wham-bam-thank-you-ma’am, apocalypse, and god given ass, but radiating through it all, as resonant for me as the brazen sexuality, was convivial energy. Bowie, et al, captured a gang-like essence, like the early Beatles recordings, except in rock drag, and with more overt sex references. This was a new way to be friends, and I wanted it.

With Ziggy, laughter hangs in the room sound; an overtone of laddishness hums through, like a special microphone had been set up to capture the sonics of blossoming friendship. It rocks, yes, and it’s sexy, yes, but also, Ziggy reeks of fun.

But for one song (“It Ain’t Easy”), Bowie wrote the album, but you need only listen to the demo of “Ziggy Stardust” (the song) to know he had a lot of help making it epic. And he celebrated that help, brought it to the stage, made it part of the show. I am bringing this rock and roll to you with my pals. Please enjoy us! Not me, but us.

[embedyt] http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vAX5hiKXnFg[/embedyt]

To make this song – and, indeed, the whole album – fly, Bowie tapped producer Ken Scott (also helmsman behind Hunky Dory), indispensable guitarist/keyboardist Mick Ronson, drummer Mick “Woody” Woodmansey, and bassist Trevor Bolder. These were his Spiders from Mars, his droogs, blue collar boys who initially balked at their boss’s insistence they wear makeup onstage, but became very enthusiastic when it helped “pull the birds.”

In the song “Ziggy Stardust,” we get Ronson’s majestic interpretation of David’s riff, aping a trumpet fanfare. Crucially, as with much of Ronson’s electric, Bowie doubles it with his twelve-string acoustic, creating a meaty, distinctive texture (used throughout the album and later, on the tour.) David announces himself with an off-microphone yelp, a high pitched ooooo yeah, and an orgasmic ah, then, in a nasal, Lennon-y snarl, he intones the narrative of rock n’ roll egomaniac Ziggy. (He would eventually abandon this vocal style for a burnished baritone, but when he used it, and when he reached for the dizzy high notes during this period, it was thrilling.)

As his mates bear him up with cymbal splashes, drum rolls, and muscular riffing, Bowie delivers a conversational vocal, reminiscent of French chanson tradition. Although it is rarely remarked upon, he is not Ziggy in this song; he is an anonymous, gossipy band member, a Spider from Mars, digging into his frontman’s beauty, his ego, and his downfall. Bowie-as-Spider conveys remorse, fascination, envy, revenge, schadenfreude, and lust. Quite impressive storytelling, that. Motoring it along, the chord changes are both familiar and unpredictable. (That’s an unexpected E major when he sings I had to break up the band, in case you’re interested. For years I thought it was D.)

But understand: this song isn’t just Bowie. It’s a band in a room, playing together in real time. You cannot fake this sound, this musical conversation. It cannot be imported via technology. You can put a man on the Moon (or Mars) but you cannot do that.

Not long after Todd gave me the album, the conversation that was our friendship entered an exciting phase. We now had a vista on which to dream and fantasize together. We began making music, entering recording studios, and trying to be like Bowie and his mates.

So, perhaps because of my own story, what I hear in “Ziggy Stardust” and most of Bowie’s 70s oeuvre is friendship. The sound of a collective greater than the sum of its parts, emitting the shimmering “other” energy that comes from connection. A band of excellent companions, up against it, adventuring, no place else they’d rather be. As I now know, it is in that realm where the impossible seems, and sometimes becomes, possible.

David’s music brought much companionship to the aural plane. His conversations with Eno, Alomar, Visconti, Osterberg, Rodgers, and Reznor remain for our pleasure. His longtime touring band also radiated soul loving connection.

Like all great friendships, Bowie was at his best, to my ears, when he was with his friends. Similarly, I have been at my best in friendships that are long, winding conversations, blissfully unconscious of time, on intimate terms with surprise sunrises, throats sore from talking, from singing together. I know what that sounds like.

David Bowie’s death, like Todd’s death in 2004, ends a lifetime of artistic conversations in sound, movement, lyrics, and symbol. My heart breaks for Bowie’s surviving collaborators and friends, and of course for his family. We fans are lucky indeed to enjoy the surviving musical “talks” of this great artist and his partners. Their dialogues reach beyond binary sexuality, beyond sex itself, and beyond time, where friendship captured in recorded sound lives on.

[embedyt] http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0IKvzaaAwJQ[/embedyt]

JANET STEEN – “Wild Is the Wind” — Station to Station (1976)

I was afraid to listen back on this song. I’m damn sad that Bowie died—it has hit me about as hard as any famous person’s death—and the parting gesture of his last record, Blackstar, is so astonishing it makes it somehow even harder to absorb (he was doing all that for us, I keep thinking, when he was sick?).

But back to “Wild Is the Wind,” from four decades ago. It’s not an original Bowie composition (it was written by Dimitri Tiomkin and Ned Washington and originally sung by Johnny Mathis, and also famously done by Nina Simone) but he owns it as much as any of his songs. I bought the vinyl of Station to Station in the early 80s and it has remained probably my favorite Bowie record. And this song in particular is the one I remember re-situating the needle on, again and again. It always felt like Bowie the man, not Bowie the performer. I was and am still undone by the emotion in it. It’s a song about being hopelessly in love, and Bowie imparts the feeling, as well as anyone I can imagine, of how really precarious and terrible a state that can be. Now the man is gone and it sounds even sadder, and better, than before.

BRENT JENSEN (author of All my Favorite People are Broken) – “Sweet Thing” — Diamond Dogs (1974)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BQvmmRHPiYA

At the height of my obsession with The Thin White Duke, my fascination with the impossible vastness of his music compelled me to try to step inside his songs, to get closer to them. If I could do that, I could in turn get closer to the man himself – David Bowie.

In my mind, there was no more powerful invitation to do so than via “Sweet Thing” from his Diamond Dogs album – a record that came after the glam-bam blitzkrieg of Ziggy Stardust and before the smooth finesse of Young Americans. For its time, the release seemed to betray David Bowie’s sudden uncertainty in direction, of where next to go. “Sweet Thing” lay embedded directly at the center of this notion.

Before I continue, it’s probably worth mentioning though “Sweet Thing” is complicated by an interlude piece placed directly in the middle of the song called “Candidate”, I wish it weren’t. If I’m close enough to the player I’ll often skip “Candidate” to go right from “Sweet Thing” to “Sweet Thing (Reprise)”, as I’ve never considered the interlude purposeful. This is likely because I was so compelled by the wounded charm of the main idea of the song that I saw no need to obscure such a genuine position.

The genuine position of “Sweet Thing” is in fact one of fragility, and this is what makes it so attractive to me. For the first time, it felt like the ever-mysterious Bowie wasn’t mysterious at all. “Sweet Thing” was like being afforded a glimpse behind the curtain and seeing Bowie for what he really was during that period – scared and lonely. Diamond Dogs was a record borne of a failed bid to theatricalize George Orwell’s 1984, and while it superficially showcased an Orwellian lack of confidence in the future, given his worsening cocaine habit it was also an intentional metaphor for Bowie’s uncertainties in his own.

And now, in this moment following his passing I sit with head bowed, embarrassed by the grotesque exhilaration I feel while listening to “Sweet Thing” over and over – David Bowie’s most heartbreaking song is lent added poignancy by the fact that he’s gone. Before “Sweet Thing”, Bowie’s musical canon offered loads of bold and daring music that challenged my perceptions. In fact, I would credit him with changing the way I actually listened to music. But the misery inside “Sweet Thing” scored even deeper. Bowie’s message had never before carried such veracity, and it humanized him in my eyes. It marked the first time I felt I could relate to him, as though he were newly vulnerable; seeking connection with earnest words delivered through beautifully lilting melodies and a swelling crescendo that makes my skin vibrate each and every time I listen. As resolutely alien as he had previously been, now Bowie seemed just on the other side of the speaker, right there – reaching out.

Just like me. Just like the rest of us.

SEAN BEAUDOIN – “Lightning Frightening” — The Man Who Sold the World (1970)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D43KTJZDCWc

I mean, for one thing, the song rocks. Let’s not forget in the midst of earnest homages and encomiums just how important that is. It just has a solid groove, pure beat, pretending to be a bluesy toss-off, but absolutely bubbling with awareness of everything to come, from Swinging London to Swinging Santa Monica to Swinging Mars. It’s got strained but soulful vocals, the signature nasal delivery, and a sprawl of lyrics that make it immediately okay to go ahead and put the moves on the world. Not to mention be as butch as you want, as femme as you like, to fuck whatever feels right–and in the meantime resurrect Iggy Pop, transform Lou Reed, dance a Berlin Waltz on Brian Eno’s skull, juke like a West Philly rude boy, get all posh like the Whitest of Dukes, strap on a red wig and some makeup, become everything and nothing at all.

Lightning Frightening (not even on the original album) has all of Bowie in one song, from minimalism to maximalism and back, everything he was born to be and that he would become. The driving bass line, the carnival time changes, the mad insect backing vocals, harp and resonator and saxophone. Yes, the man could play his own sax lines.

To me, the most interesting aspect of Bowie was that he managed to find a way, musically and personally, to refuse to give purchase to those desperate to interpret instead of just listen. His world and words existed in a airless metal room, inspiring and playful and creative, but without an encompassing policy or grind or even palpable message–unless it was the beauty of having nothing to wave flags at, or for. It’s a rare achievement–“make of me what you will, or just make it with me, but I will remain in orbit either way.”

All music is derivative, it’s just that some is less so. David Bowie’s appropriation is somehow more pure and giddily adventurous, completely disdainful of critique. From semi-hippie showing his loaf in silk pants to glam acoustic recluse, through the pre-punk avant trans Manhattan art scene, to aliens and coke fiends and acid-crazed kosmonauts, he inhabited them all with grace, and never as a gimmick. Everything was an extension of bedrock soul-fueled chops, his desire to both paint and inhabit a canvas, one that I’ve had hanging happily in the back of my mind for decades.

For the last week, my wife has kept saying, “Why are you so grumpy?” but I’ve refused to answer, mainly because answering at all felt so meaningless and petty. There is no answer! There are no words! And then finally last night, while listening to outtakes from Young Americans (so much good stuff was kept off that album. What was Luther Vandross thinking?) I told her and she laughed. Not in a mean way, just that Bowie has never meant to her what he means to me and so she couldn’t understand why I felt like I’d been punched in the neck, like someone had cracked me open and stolen one of my ribs. But who has time to mourn when there’s stuff to clean and homework to oversee and Mac n’ Cheese to make, and it wasn’t like I knew him, right?

Right?

David Bowie was a better creature than the rest of us.

JAMIE BLAINE – “Fame” — Young Americans (1975)

I was a frequent peruser at our small town mall Musicland, happy to spend hours browsing the racks on any given afternoon. Country, R&B, Jazz, Metal, Rock, Rap, New Age, New Wave – I loved it all.

But Bowie’s Lodger always gave me pause. I think it was the sprawled-out, broken nose Polaroid thing. Kooky weird like David Allen Coe or GWAR was fine but this was weird in a way I wasn’t sure I liked. Still, I would study the front and back cover every time, trying to decide what this broke and twisted singer might sound like.

Musicland had an assistant manager named Carrie who wore stack-heel boots, super-tight jeans and had hair like a horse’s mane. I was staring at Lodger one day when she caught my sleeve.

“How old are you?” she asked.

“Nine,” I replied.

Carrie gently pried Lodger from my hand. “You’re not old enough to appreciate Bowie yet. Come back maybe in junior high.”

My casual interest was suddenly burning. “What if I want to buy it now?”

“Tell ya what,” Carrie said. She slid her sparkly black thumbnail through the cellophane and clomped towards the front. “I’ll put it on. If you still want it, I’ll sell it to you on my discount.”

I stood in the aisle with my head cocked, listening. To my fourth-grade ears Lodger sounded like a bevy of drunk uncles after a Sunday Monty Python binge. Soon as Carrie’s back was turned, I bolted out the door.

FAST FORWARD / JUNIOR HIGH

They bussed me to an all-black school where I was promptly assigned to marching band. I had been in band before but we slogged through tunes like “Michael, Row Your Boat Ashore” and the theme from ALF. Now I was expected to play big bass drum on “Brick House” while doing the Electric Slide.

The director’s name was Cookie and he was a muscled-up guy with a big old-school Afro – but bald on top with hair only on the sides, so he looked like a cross between George Jefferson and Apollo Creed. One day he rolled in video to teach us a new song. “Blaine!” Cookie called back to me, “we’re doing this one for you, my man.”

Cookie played an old clip from Soul Train and there on stage was some impossibly skinny white dude with bright orange hair, a yellow shirt and royal blue suit.

“What’s this?” I asked. “Is the Joker making records now?”

Everybody laughed (except the clarinet section) while Cookie shook his head. “Dang, son,” he said. “You don’t know who David Bowie is?”

“That’s Bowie?” I asked. “The broke nose dude?”

This is when it hit me: It was the first fall chill on a Thursday night with the smell of turf sweat and Gatorade around me. I was in a headstand over my bass on the thirty yard line, stadium lights blinding my eyes, doing the Robot upside down and stuttering out the syncopated line from “Fame.”

Sweet Carrie was right. The time for Bowie was now.

LARRY BENNER – “China Girl”– Let’s Dance (1983)

If you ever spent much time reading those big rock encyclopedias once found lying on stoner’s coffee tables littered with seeds and stems, you’re probably familiar with some of the inflated anecdotes about the seventies in West Berlin, when a raft of American and English pop stars huddled in self-imposed exile, mainlining heroin and hanging out with Krautrock bands like Neu! and fringe members of the Baader-Meinhof terrorist group.

One of those anecdotes goes something like this: Iggy Pop was in Berlin, strung out on heroin, and David Bowie—having recognized Iggy as a “visionary genius”—flew in and saved him. He got Pop off the junk and steered him into the studio, where they recorded The Idiot together over the course of two months. Then they banged out Lust for Life in a couple of weeks, an album that features The Passenger—a song beloved by Berliners for its references the S-Bahn—and the titular Lust For Life—an anthem of liquor and drugs that got way too much airplay in the nineties due to its inclusion in the Trainspotting soundtrack. (And later, in a bizarre twist—ended up as the bouncy, irrepressible theme song for Carnival Cruise Lines.)

Iggy Pop has categorically denied this version of events, claiming that he and Bowie enjoyed an artistic collaboration and nothing more. Bowie was just more into coke than heroin is all. There was no salvation; they were both just addicts. The story was the invention of rock journalists, designed to sell big rock encyclopedias to stoners.

Whatever the truth, The Idiot has been one of my favorite albums ever since I discovered it in my twenties. Partly because it is the perfect combination of psychedelic fuzz and punk minimalism—if you ask me—but mostly because the album features the original version of the Bowie/Pop coauthored China Girl.

I was already familiar with the Bowie version. Released as the second single off Let’s Dance, it was a radio and MTV hit, an unanticipated mainstream pop success. I liked the song, and I liked the video—a lighthearted romp, considering the lyrics cover the negative effects of colonialism—wherein Bowie and an Asian girlfriend frolic through several disjointed, playful scenarios: they mug and stick their tongues out at each other, he throws a bowl full of steaming noodles into the air, he falls into bed with her while clutching a juice box (evidently a potent symbol of cultural vampirism in the early eighties.)

But it wasn’t until I heard the original Iggy Pop/David Bowie version on The Idiot that I began to realize how great it was. They’re almost two different songs. Bowie’s version is a sparse disco number—barren synth hooks bounded by minimalist metronomic drums. It is arguably the stronger version. But Iggy’s version is weaker, and—I would contend—better because of it. The Idiot version is loud, operatic, sloppy. From the seemingly random plink/plank/plunk ofthe opening glockenspiel, to Iggy’s intentionally awkward vibrato in the verses, to his raw howl in the climactic:

I stumble into town / just like a sacred cow

visions of swastikas in my head / and plans for everyone.

—to the long, densely layered fuzz guitar outro—it’s the same song, but without the pop ease of access. It’s raw, emotional, and strange.

So, I spent the next few decades disparaging the Bowie version and hyping the Pop version . . . But they’re both Bowie versions, really. In The Idiot, Bowie is everywhere on the track, and not just on the keyboard and in the backing vocals. His production is one of the reasons the song is great.

Bowie has long been characterized—and seldom in a good way—as a chameleon, or as a sort of P.T. Barnum, capable of recognizing talent and procuring it, of synthesizing diverse elements into a stylized pop package . . . to mimic and combine, but not to originate. And if you listen to the three tribute songs on Hunky Dory (Queen Bitch, Song For Bob Dylan, and Andy Warhol) it is easy to recognize an imitative admirer. One who adopts the styles of others as effortlessly as trying on a jacket, or a new hairstyle.

But this is too simple. Bowie the impostor, Bowie the Warholian fake—is just another sort of anecdote, another attempt by rock journalists to categorize an indefinable genius,to boil him down to his constituent parts and convert it into copy. For me, Bowie’s greatness can be witnessed, not in words, or in characterizations, or in anecdotes, but in the spectrum between the two versions of China Girl. They represent two poles of talent,Bowie as experimental producer, willing to break new ground, and Bowie as pop stylist, who knows a good hook when he hears one, and just wants us to get off our asses and dance.

WARREN ZANES (former VP, Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, author of Petty, The Biography)

Without making it his business, David Bowie managed to show us how limited we often are in how we conceive of the singer-songwriter. He dispensed with so much that we thought defined the singer-songwriter. Then he heaped all kinds of other stuff — theater, costume, technology, narrative, dance, whatever interested him at any one time–on top of that basic man-with-song-and-guitar thing, forcing everyone to reckon with it all. His disruptions were among the very best and most lasting in popular music.

Maybe I even counted on him in such a way that at times I forgot how lucky we were to have him. It seemed like he’d always be there, and it was anybody’s guess what might be coming next. His death knocked me back a few feet, I think. It certainly gave me occasion to remember again that rock and roll is at its best in the hands of the rule breakers. And he was a King among them, laughing all the way.

JOE DALY (rock journalist, Metal Hammer, Classic Rock) “Heroes” – Heroes (1977)

For an artist whose breathlessly-ambitious catalog showcases some of modern music’s most successful forays into art rock and experimentalism, I find myself deeply connected to one of Bowie’s most commercial, straight-down-the-middle tracks — Heroes.

I first heard it while listening to Boston’s WBCN in my bedroom one night, instantly arrested by that sugary Beach Boys rhythm chugging in the background and Brian Eno’s soulfully synthed-out guitar lines dancing in the ether. This side of Bowie was entirely new to me — his albums before that had wholly transcended the overpolished generic cock rock clogging the FM dial in the 70s, bursting with punchy, swiveling grooves while at the same time, buzzing with a thrilling sense of intellectual subversion. Then came “Heroes,” this utterly gorgeous anthem with simple yet evocative lyrics that spoke directly to my bloody teenage heart.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m3SjCzA71eM

I had a crush on this girl from work who lived up the road and I’m not sure where I found the resolve, but I found myself walking to her house one night with “Heroes” playing on my Walkman. With Bowie in my ear and a spring in my step, I reached her front door and knocked. Without getting into the grisly details, let’s fast forward to me walking home along approximately sixty seconds later. Though “Heroes” would immediately and inextricably become linked with soul-whipping teenage heartbreak, I never stopped loving the song.

As I type this sentence, I can feel the balmy summer air on my face, walking beneath the streetlights and listening to “Heroes.”

DANIEL FULLER (Music Writer, Orlando) — “Queen Bitch,” Hunky Dory (1971)

Of all the songs in Bowie’s catalog, “Queen Bitch” is probably the most deservedly named. And yes, mam, it’s bitchy as hell — a nasty, distorted guitar riff, masculine-then-fem vocals, and hip-thrusting rhythms. Released the year I was born in 1971, I can’t quite imagine hearing it then. This is the definitive glam-rock anthem before there was one (with appropriate apologies to Marc Bolan).

And the story? Scandalous. A dude watches his boyfriend pick up a prostitute — could be a he or she, gender typing be damned — from the street below their 11th-story apartment. Of course, the song sounds a helluva-like Lou Reed and the Velvet Underground. And with good reason — Bowie was one of a handful of U.K. musicians that listened to the Velvets during their initial run, and covered them early on. Yep, the track liberally borrows from both ‘Waiting for the Man” and “Sweet Jane.” Though Bowie’s then guitar-god Mick Ronson later admitted the four-chord progression was initially ripped from Eddie Cochran’s “Three Steps to Heaven.”

But if ‘Queen Bitch” ultimately wears Uncle Lou’s street-wise NYC guitars and glib tone as a strap-on, it dresses it up with satin and sass. While the verses certainly reflect this influence, the chorus is pure Bowie — no one else could gleefully boast of being able to do it “better than that” in a snippy critique of his beau’s alleyway action.

And what of it? The next year would see the release of The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars propel Bowie into pop-star orbit. In many ways, he never came back down (or sound this trashy again.) But that’s what so cool about “Queen Bitch” — you’re getting a glimpse of the future, whether you like it or not.

And it sounds great really loud.

SEAN MURPHY – “Ashes to Ashes” — Scary Monsters & Super Creeps (1980)

Sordid details following. It’s all in here: summing up practically everything from the ‘70s and previewing so many trends to follow in the ‘80s. Everyone heard this, even if they weren’t listening. In this one song you have punk melting down prog and fermenting new wave, done, typically, without a safety net. One flash of light, but no smoking pistol. Nothing by anyone else before or since sounds anything like this. Bowie made being beyond scrutiny a career move, yet if any individual song could summarize (yeah right) what he was about, “Ashes to Ashes” showcases the elements that made him so inimitable: the esoteric conceptualizing, the wit, the irony, the humor (!) and the ways he savors the English language, less a poet than a word painter. (Want an axe to break the ice: There’s an image a young listener can really get his mind warped around. To discover, later, it’s a cheeky riff on Kafka’s famous dictum? Mind = Blown.) So what’s it about? Like much of Bowie’s best work, it’s obvious and impossible to pinpoint a meaning or message.

Strung out in heaven’s high hitting an all-time low: a line leaving little to the imagination; it could be the elevator pitch for the movie, it could encapsulate the willful contradictions of Bowie’s career, it could be a commentary on science, capitalism or Art Itself. For starters. Certainly autobiographical elements abound (Time and again I tell myself, I’ll stay clean tonight), and with the name-check of Major Tom, a brilliant case of art imitating life or vice versa.

I’ve heard a rumour from Ground Control: Where “Space Oddity” which, incidentally, closed out the previous decade, manages to balance discovery and despair, “Ashes to Ashes” is all about wizened desolation (The shrieking of nothing is killing). And could any artist aside from Bowie execute this burnt-out holler from Beyond and make it swing? Fun to funky, indeed. A barren soul, a heavy heart, scared eyes following those green wheels: the diary of a madman, the madcap laughs, you’d better not mess with Major Tom.

I’m stuck with a valuable friend: I never done good things (I never done good things), I never done bad things (I never done bad things), I never did anything out of the blue, woah-oh (woah-oh). That last echoed “woah-oh”: deadpan, droll, disturbing. (Did we even discuss the video? The more said about it, the better.) No heroes, here. Now he’s gone and our planet’s glowing. I’ve loved. All I’ve needed: love. Maybe that’s the message. Of the song, of his life, of any of our lives. I’m happy. Hope you’re happy, too. What he said.

BEBE BUELL (author, Rebel Heart: An American Rock And Roll Journey) “Lazarus” — Blackstar (2016)

Look up here, I’m in heaven

I’ve got scars that can’t be seen

I was there the night Bowie showed up at Max’s Kansas City and we started a fast friendship that would last a lifetime. I took him to see the New York Dolls, The Empire State Building, The Rockettes. David’s dream was to play Radio City Music Hall. He did and Todd and I were right there for it in the third row.

David was the most talented and creative genius I have ever known – and I’ve known many. He could find art in anything. His dedication to discovering the noises inside his head and bring it to fruition was amazing. We all have those sounds inside but how many can truly bring them forth?

“Lazarus” was David’s take on spirituality, on God and life and death. He knew he was dying and that was his way of saying goodbye. To give that gift even in death? To be willing to swallow your pride and be that vulnerable? That’s a true artist. That is truly profound.

David Bowie had the best entrance ever in pop culture and the best exit as well.

I relish, result in I found just what I used to be looking for.

You’ve ended my 4 day long hunt! God Bless you man. Have a great day.

Bye

I have read so many content on the topic of the blogger lovers

except this piece of writing is really a nice post, keep it up.

Pingback: David Bowie: Ashes to Ashes (Revisited) - Murphy's Law